The Singapore story depicted in textbooks is about a country becoming an economic miracle built by our forefathers who toiled through the 20th century.

As the narrative goes, Singapore went from being a sleepy fishing port to being colonised by the British from 1819. The Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II, and a struggle for self-governance ensued.

Eventually, the British withdrew and Singapore became a part of Malaysia in 1963, only to become an independent country in 1965.

Since then, Singapore has consistently defined itself as a multi-religious and multi-ethnic society, consisting of four major groups, Chinese, Malays, Indians, and Eurasians.

However, there are in fact many hidden stories of people and communities with narratives that enrich and cast a fuller gaze on the “Singaporean identity”, some parts of which may have been forgotten over the years.

Here are some of those narratives.

The Kristang Language

The Kristang language originated in the 16th century from the Portuguese-Eurasians - descendants of Portuguese settlers who married local Malay women.

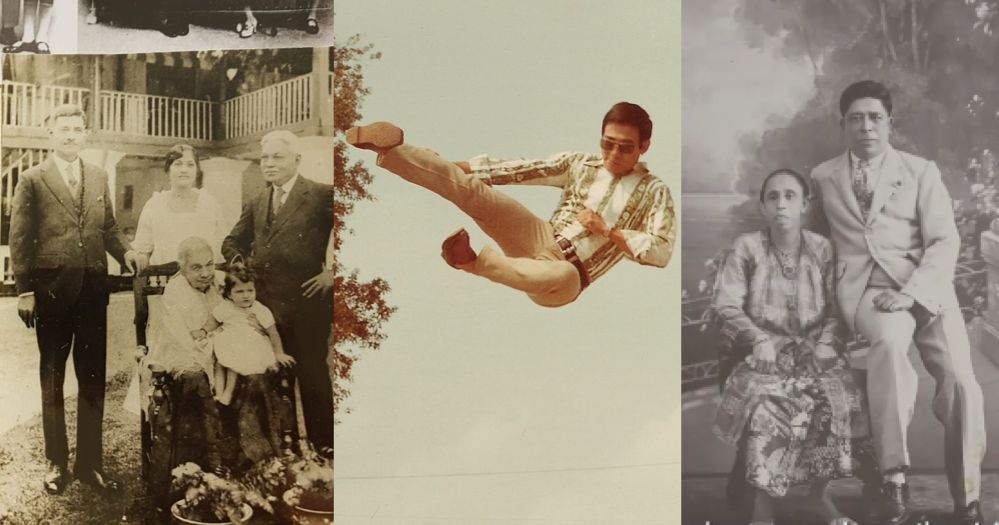

Family photo of Reginald Tessensohn. Source: Kevin Martens Wong

Family photo of Reginald Tessensohn. Source: Kevin Martens Wong

Kristang’s uniqueness is a result of its vocabulary having Portuguese roots, while borrowing its grammatical form from Malay. Reflecting the mixed nature of the Portuguese-Eurasian community, Kristang has, over the years, evolved to further incorporate vocabulary from Dutch, English, and even dialects such as Hokkien, Hakka and Cantonese.

From more than 2,000 Kristang speakers in the 19th century, there are only around 50 fluent speakers left in Singapore - most relying on memories of the language from their grandparents’ and parents’ days. They were never directly taught the language, but rather learnt through listening to conversations amongst the older generation at home.

Photo of Frederick Martens (left) and Edwin Tessensohn and his family (right) Source: Kevin Martens Wong

Photo of Frederick Martens (left) and Edwin Tessensohn and his family (right) Source: Kevin Martens Wong

Kristang saw a decline because it was regarded as economically irrelevant when Singapore was a British colony. English was the working language and fluent speakers of English were more likely to land better paying civil service jobs.

Moreover, Kristang was viewed as a broken language that would “spoil one’s English”. Hence, children were discouraged from learning it.

The language was also sidelined during the creation of our National Identity as Kristang was not recognised as an official language. Newly-independent Singapore had decided on English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil, which were taught in schools and spoken and written nationwide..

Up till today, Kristang does not exist in an official written form. As a spoken language, Kristang was rarely recorded. Hence, there is no standardised spelling or pronunciation system for its words. Also, because it has been in decline for a long period, there are now gaps in the vocabulary -- modern terms that exist in English have not been translated to Kristang.

Hence, Kristang slowly faded from everyday use, and has since lost its utility. However, while there are no economic reasons to embrace Kristang again, it will always be a fragment of the heritage shared by Portuguese-Eurasians.

Who is Tony Yeow?

Tony Yeow was a pioneer independent filmmaker, long before the likes of Jack Neo and Eric Khoo became household names in the industry.

Yeow started out as a producer in the early days of television and radio broadcasting in Singapore, where he witnessed the announcement of Singapore’s separation from the Federation of Malaysia, and also produced government campaigns such as “Stop At Two” in the 1960s. He then ventured into filmmaking later in his career.

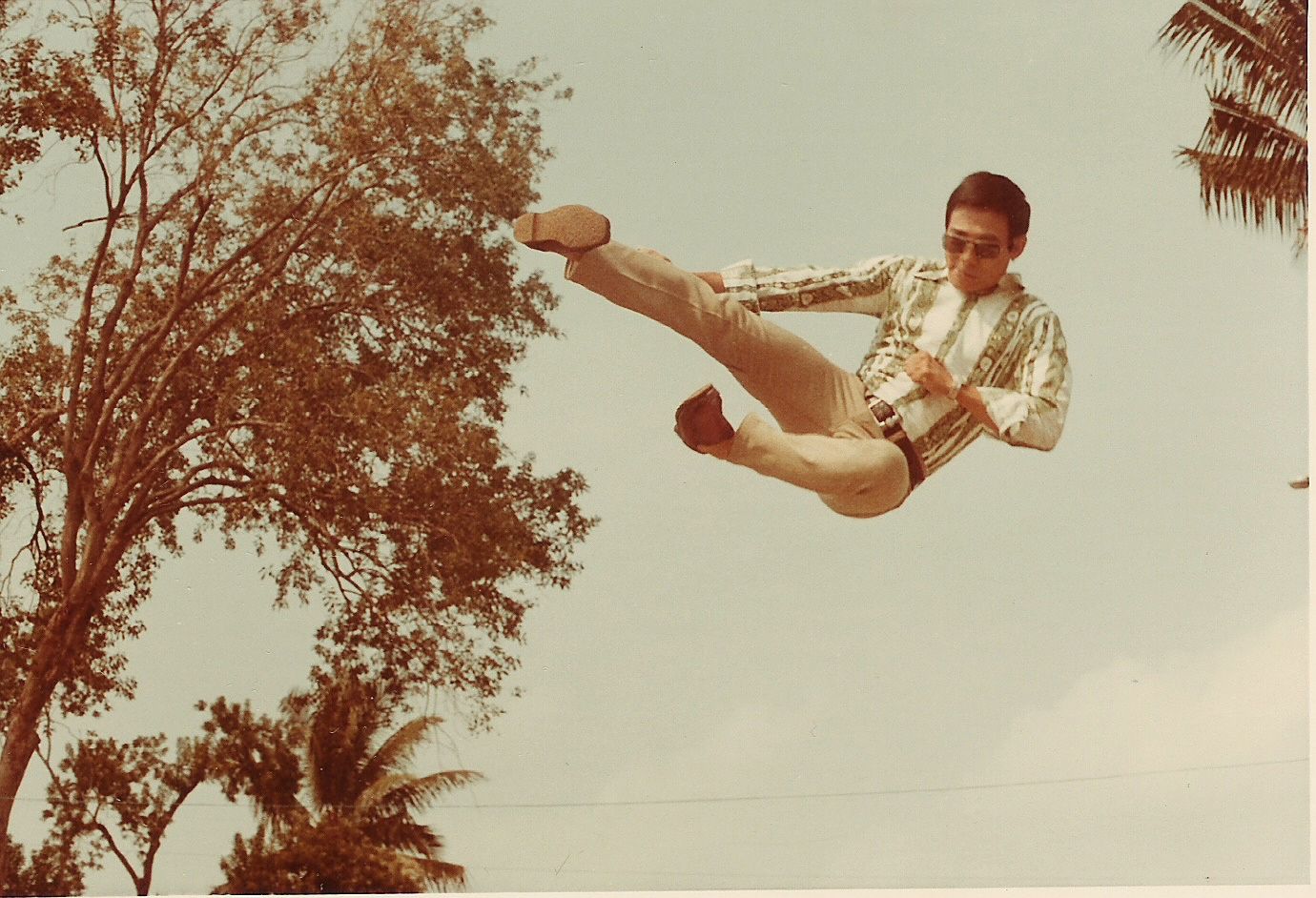

Tony Yeow. Source: Tony’s Long March

Tony Yeow. Source: Tony’s Long March

Born in a time when filmmaking was hardly considered a glamorous job, Yeow struggled in a Singapore cinema landscape dominated by major studios such as Shaw and Cathay-Keris.

In the fledgling Singapore film industry which had less structure then, people were free to attempt creation through their limited knowledge of filmmaking, as they were also less afraid of making mistakes.

The end-product was therefore often refreshing, out of this world, but always genuine.

Some of Yeow’s pieces turned out to contain daring themes involving sex and gore. He was, in essence, an artist ahead of his time.

Still from Tony’s Long March.

Still from Tony’s Long March.

In his lifetime, Yeow never actually produced a film that won commercial success or critical acclaim.

For example, his 1973 gongfu flick Ring of Fury was meant to be his prized production, complete with stylish camerawork and realistic fights.

However, the movie was banned because its depiction of gangsterism and crime was deemed unsuitable, and too violent for a Singapore that was, during that era, undergoing a massive clean up.

Gangs were prevalent in the 1960s and 70s, and the police took the crackdown on crime seriously then. Many gang members were either jailed, or detained without trial under the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act (then referred to as Section 55).

From the set of Ring of Fury. Source: Tony’s Long March

From the set of Ring of Fury. Source: Tony’s Long March

A fight scene from Ring of Fury. Source: Tony’s Long March

A fight scene from Ring of Fury. Source: Tony’s Long March

Nevertheless, while Yeow’s career was fraught with challenges and disappointments, he never gave up writing scripts and producing films.

Up till a few years before he passed on in 2015, Yeow was still passionate about his craft, developing scripts that he hoped would one day be made into films he believed would shine. He was motivated by his love for film, and optimism for future opportunities.

Although he never attained phenomenal success commercially or critically, what Yeow achieved was far more noble: His persistence and contribution to the nascent local film scene shaped the path for today’s filmmakers to further their art.

The Chetti Melakans

The Chetti Melakans are descended from Tamil merchants who travelled to Melaka for trade in the 14th and 15th centuries.

These Tamils eventually settled down and married local Malay women -- their resulting offspring called themselves “Chetti Melakan”, which translated to Melakan traders.

Source: Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook Page

Source: Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook Page

In pursuit of greater fortunes, some Chettis eventually moved to Singapore and settled in modern day Little India. Although this Indian community has the longest history in Singapore, it is the least known due to the cross cultural assimilation.

Over the years, the Chettis who married local women adapted the Malay way of life through language, customs, food and even dressing. For example, the men are garbed in sarongs while the women are dressed similarly to the Peranakan Kebaya. Such assimilation into the Malay culture led to a gradual loss in display of the Chetti’s Indian culture

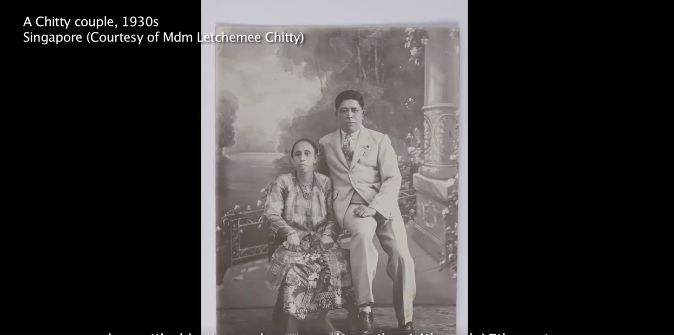

Screenshot from Roots.sg video

Screenshot from Roots.sg video

Originally Hindu practitioners, some of these Tamil men also saw their travels to Singapore as an escape from the strict caste system in India, where nuptials were dictated by parental decisions, and inter-caste marriages were forbidden.

In embracing their new-found freedom, these Tamils who married local women, ended up converting to Islam, rendering them and their Chetti descendants further removed from their original cultural roots.

The Chettis also grew to become more proficient in their maternal mother tongue, Malay, and in the process, lost their mastery of their paternal mother tongue, Tamil.

This was presumably because as their mothers were most likely to have raised and spent more time with them at home, Chetti children had greater exposure to their mother’s primary language.

The culture of the Chettis was further diluted through multiple inter-racial marriages of the later generations in Singapore, resulting in their cultural practices involving both Chinese and Malay influences. For example, some of their practices in religious rituals were influenced by Chinese culture, such as the use of worship objects, and offering of fruits.

Source: Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook Page

Source: Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook Page

Over time, the Chettis found themselves overshadowed by other communities due to their willingness and ability to assimilate into other cultures, as a means of being accepted by local society.

---

These are but some of the unearthed stories that are featured in Lumination.

In conjunction with National Day, and held throughout the month of August at The Arts House, the inaugural edition of Lumination sets its sights on uncovering Singapore’s hidden stories - Hidden people, hidden spaces, hidden words, hidden histories.

This is a definite must-come for history lovers and culture buffs, who are keen to immerse themselves in these less discussed Singapore stories. However, the wide range of activities (workshops, exhibitions, old school games, talks, performances, and many more) makes the programme digestible enough for all to enjoy.

Where / When to go

Date: 4-5 August, 10-12 August, 2018

Time: Various timeslots

Location: The Arts House at the Old Parliament, 1 Old Parliament Lane, Singapore 179429

This sponsored post by The Arts House made the writer realise she could have wowed her JC history teacher more with these hidden stories of Singapore.

Top images from Kevin Martens Wong, Tony's Long March and Roots.sg

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.