In 1776, the late American political theorist Thomas Paine, writing in favour of American independence from Britain, gave the following line in his pamphlet, Common Sense:

"It is not in numbers, but in unity, that our great strength lies; yet our present numbers are sufficient to repel the force of all the world."

Essentially, it was a call for the Thirteen Colonies established by Britain in America to rise up together and break away from the British crown.

Some 203 years later, in 1979, Paine's maxim would be repeated once more.

This time, it was in a different region of the world under different circumstances: The uniting of five developing countries -- Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines -- under the banner of Asean against what was seen as bullying by a developed country, Australia, over international civil aviation rules.

How did it start?

In 1978, Australia's national carrier, Qantas, came under growing competition on its key air routes between Australia and Europe from a number of other airlines, including Singapore Airlines (SIA).

Coupled with the rising demand within Australia for cheaper fares from the public and travel industry, both Australia and Qantas decided to take measures to meet the demand in a manner that would secure Qantas' position.

Source: Changi Airport Facebook

Source: Changi Airport Facebook

This led to Australia's announcement of a new policy, in the middle of 1978, called the International Civil Aviation Policy (ICAP).

What did ICAP entail?

According to both Frank Frost's study Engaging the Neighbours: Australia and Asean since 1974, and the second volume of the late Lee Kuan Yew's memoirs, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, ICAP involved the following measures disadvantageous to SIA:

- Limiting the capacity of foreign airlines on routes between Australia and Europe

- Allowing only Qantas and British Airways to carry passengers point-to-point between Australia and Britain at cheap fares

- Cutting the frequency of SIA flights between Singapore and both Australia and Britain

- Guaranteeing high "load factors" -- the proportion of seats filled on flights -- for the entire flight between Australian and European ports by discouraging, via a high-cost surcharge, "stopovers" by passengers en route

- Disallowing then Thai airlines Thai International from taking passengers from Singapore, an intermediate point, onwards to Australia

As Frost elaborates, the Australian justified this policy on the grounds that it was "in accord with the norms of international airline negotiating procedures, and that it was an assertion of legitimate Australian economic interests".

A serious issue for Singapore

Needless to say, ICAP was a policy that had serious repercussions for Singapore compared to the rest of Asean.

This was due to the way in which it adversely impacted SIA.

As Frost notes, by 1977, SIA "had achieved the highest passenger and freight load factors of any international airline" and by 1978, SIA "accounted for over 3 percent of the country’s gross national product".

Moreover, a major factor for SIA's successful growth was its capture of up to 30 percent of the traffic on the Australia-Europe air routes.

As such, "No other airline from an Asean member was as dependent on the Australia to Europe traffic to the same degree as SIA."

Loss of revenue

The implementation of ICAP meant a serious reduction in traffic for SIA, a blow to Singapore's tourism, which was highly reliant on passengers making a stopover in Singapore, and by extension, a blow to Singapore's gross national product as well.

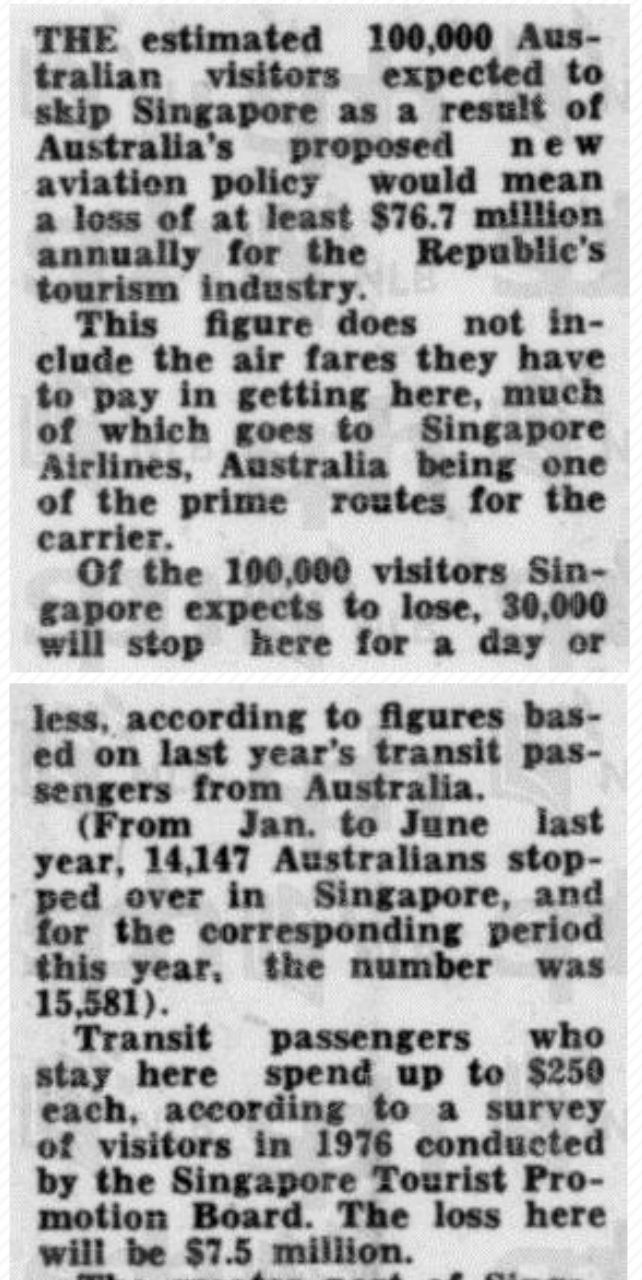

According to The Straits Times on Dec. 10, 1978, ICAP resulted in 100,000 Australian tourists skipping Singapore, and the tourism industry made a loss of S$76.7 million.

Source: Newspaper SG

Source: Newspaper SG

And this figure did not include the air fares that the Australians pay to get here, "much of which" went to SIA.

To top it off, this was not an issue that Singapore's Asean neighbours necessarily sympathised with.

After all, it had only been six years prior to the ICAP issue when Malaysia-Singapore Airlines split off into Malaysian Airways System (MAS) and SIA, under extremely acrimonious circumstances.

ICAP was an issue where, as Lee recalled, "the Australians nearly succeeded in isolating Singapore and dividing the Asean countries, playing one against the other", by attempting to "discuss the issue only bilaterally with each affected country".

But it did not stop Singapore from successfully mobilising Asean against Australia.

Reframing the problem

To get the rest of Asean on Singapore's side, Singapore framed the issue within the context of "North-South economic relations" and took additional steps to sweeten backing Singapore's cause.

Lee instructed Singaporean officials to make enough concessions to Malaysia and Thailand, the two most unsympathetic to Singapore's issue, so that they would "join us in the fight".

For Malaysia, officials were advised to give "enough concessions to Malaysian Airlines for Malaysia to stay united in Asean".

For the Thais, Lee leveraged his close relationship with then Thai Prime Minister General Kriangsak to inform him that Australia was engaging in a "blatantly protectionist" move and that they were out to "exploit the differences between Asean by offering inducements and threats".

Roping in the Philippines and Indonesia was relatively easier given that in 1976, Australia had caused unhappiness with its imposition of tariffs on textiles, clothing and footwear -- products that these countries were actively exporting.

It was a move which Lee called during a speech in 1977:

"... a source of considerable frustration and bitterness on the part of countries like the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, which feel this is a one-sided business -- of a very wealthy continent, sparsely populated, with enormous natural resources, not yet fully developed with an industrial capacity commensurate with those resources, yet wanting to make all the little things."

This made the ground fertile for Singapore's cause especially once, as Frost states, ICAP was painted as:

"... an act of discrimination against a successful airline from a rapidly developing Third World state, which was being penalised for its success in competing in the Western-dominated, technically sophisticated airline business."

Singapore received some unintentional help from Australia as well, thanks in part to the behaviour by its officials, which helped to escalate the issue to an Asean-wide problem.

Australia's tough talk damaged own standing

As Lee recounted, "Asean solidarity hardened after a meeting when the Australian secretary for transport spoke in tough terms to Asean civil aviation officials".

Upon getting wind of the incident, Mahathir Mohamed, who was the deputy prime minister and also the minister of trade and industry for Malaysia at that time, immediately hardened Malaysia's position against Australia.

Lee added that Mahathir was still seething at Australia over his visit in 1975, with the late Malaysian Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein, where both of them had been harassed by protesters that included among other things, effigy burning.

The tough talk by the Australians also irritated Indonesia, so much so that they threatened to deny Indonesian airspace to Australian aircraft.

Australia backed down

Eventually, Australia backed down.

A series of meetings from May to October 1979 ended with Australia agreeing to make no changes to SIA's frequency, routes and capacity, along with allowing other Asean airlines to have extra flights to Australia.

It was an impressive moment for Asean on the whole, as it showed a high level of cooperation between the different members on an issue that had potential for far more division than cooperation.

[related_story]

It also forced Australia, a developed country, to significantly change its policy and make concessions to developing countries, playing out Paine's maxim of strength in unity.

Frost states that this moment "constituted Asean’s single most influential external joint approach in economic relations up to 1979".

For Lee, it "was a lesson on the benefits of solidarity".

Top image from Changi Airport Facebook

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.