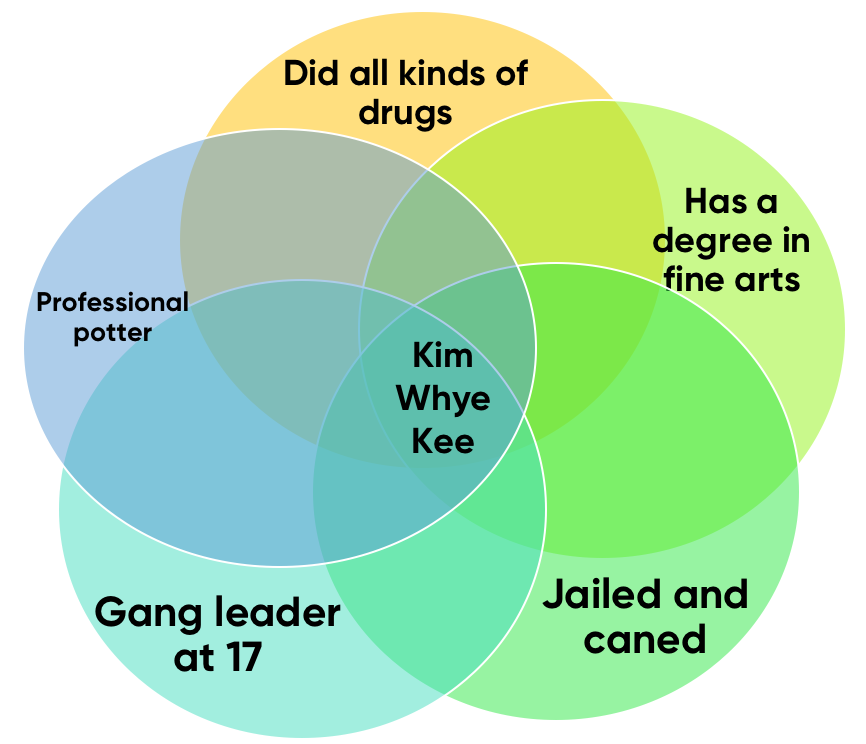

Singaporean potter Kim Whye Kee is a Venn diagram convergence of a whole bunch of life experiences and occupations you've likely not ever encountered.

Lousy Venn diagram by Jeanette Tan

Lousy Venn diagram by Jeanette Tan

He's still 38 (his birthday is in December), but as you can see, everything he's already done and knows about gangs, drugs, violence and, well, tea and pottery-making, is good enough to fill a book, and perhaps get made into a movie.

Take drugs, for instance (okay don't, but you know what we mean).

As someone who has taken "pretty much everything apart from cocaine because cocaine isn't as easy to get", Kim declares heroin to actually be less harmful to the body than ketamine.

And he probably does know what he's talking about — he was charged and sentenced to 27 months' jail time in 2003 for consuming ketamine, by the way. Why else would heroin be priced at S$15 for a quarter of a straw, as compared to S$35 for a quarter of a straw of ketamine, right?

But of course, his knowledge goes wayyy beyond the relative prices and market value of different types of drugs.

Ketamine, he adds, is also more valuable because it's more expensive to produce — it's made of multiple man-made chemicals and is seen by young drug abusers as more hip compared to heroin, generally regarded to be an "uncle" drug you'd see snorted at coffee shops.

All that said, he says the most dangerous drugs aren't the illegal ones: the likes of cough syrup and sleeping pills, chiefly because of how accessible and easily available they are.

Kim's time as a member, and then a leader of a huge — and we mean huge: more than 100 members looked to him as their towkay — gang called "2-4" (two four), has taught him that gangsterism is one that youth turn to as an alternative to a bleak life in what can be quite an unforgiving Singapore.

Especially when trapped in the viciously tough cycle of low-income/troubled family → weak academic performance → ITE → low income work/jobs.

"... when we were in secondary school, and streamed to Normal (Tech), there's no more dreams. Because the only path is ITE. It's a dead end. So most of us give up our dreams."

[related_story]

While that is a generalisation, Kim says if you asked anyone at any stage of that, they would tell you they feel the inferiority, the gloom and the overall death of their childhood hopes and dreams.

But let's talk first about how he got there.

Growing up with loanshark harassment

A screenshot from Kim's final year project installation — a short film titled "Exorcising the inner gangster". This scene superimposes a gang fight over a shot of him meditating with a Buddhist chant at the bank of the Jurong Lake.

A screenshot from Kim's final year project installation — a short film titled "Exorcising the inner gangster". This scene superimposes a gang fight over a shot of him meditating with a Buddhist chant at the bank of the Jurong Lake.

Kim's childhood was a challenging one: his hawker father cooked and sold mutton soup, later switching to chai tow kway and char kway teow. His mother assisted him at his stall, but while he was still in primary school, they divorced because his father was a serial gambler who borrowed liberally from loansharks.

And as you would expect, these folks didn't spare his dad or his young family — the sight of red paint splashed across his family gate, hell money in his letter box, fire set to his front door, and a pig's head left at the entrance were all "very common" for a very young Kim growing up in the mid-80s and early 90s, whose mother would hustle him into the bedroom, switch off the lights and hide under the covers when the runners came knocking and yelling.

He jokes that these experiences of fear and helplessness gave him a special hatred for loansharks when he became powerful and influential, and he would later on target them in fights or attacks he decided to stage on a whim.

Interestingly, this combination of neglect and anger made Kim an attractive target for gangs — he shares that in his upper primary and lower secondary years, he always found himself getting beaten up or attacked by gangs after inadvertently offending them with his louder-than-usual speech and actions.

One particularly nasty day in Sec. 2, he found himself surrounded by angry gangs in school — outside, he was beaten up by 10 people, and inside the building, another 20 jumped him, all within the span of half an hour.

Recruited, and then recruiting

But somehow, this changed — Kim and his friends were recruited by the headmen of 2-4 when they joined a lion dance troupe together. He was in Secondary 3 at the time, and it was 1996 — the year people started losing their jobs as the world slipped into the 1997 economic crisis — and so youth were neglected, their requests for money went ignored, and increasingly took matters into their own hands.

"So the gang have money, we have friends, come and join us. So once you start to recruit they all will come. Like all of a sudden, yeah, you open up a space for all of them to come."

He eventually rose to become the leader of the gang when he suddenly found himself in control of more than 100 members, younger and older than he was (17 by then, in case you were wondering).

"I'm quite good in fights because I was very very very angry. I don't understand why I cannot go to school and study like normal people. I don't understand why there is Normal (Tech), no future. I don't understand why my parents divorce. Then all this hate made me very fierce."

And he fought mostly with his bare hands — weapons were "not very gentlemanly" — and it came to a point where no one dared to challenge his authority even though "by right fighters cannot become gang leader because you cannot think well"... because he had too many fans/followers — literally the OG influencer, if you will.

The eight dots on his finger joints are tattooed on each of his hands when a gang member completes a fighting "training course". (Photo by Jason Fan)

The eight dots on his finger joints are tattooed on each of his hands when a gang member completes a fighting "training course". (Photo by Jason Fan)

At one point, he says quite matter-of-factly, he controlled the gang branches in no less than five secondary schools in the Jurong area.

Fascinatingly, he likens this to being appointed CEO of a massive, unregistered and illegal company — complete with plump salary (plenty more than S$7-8,000 per month, by the way), accountants to manage the money and disbursement to gang members as well as responsibility and jurisdiction over the safety and welfare of hundreds of young, wayward people.

And then, two years later, he got caught.

Jail, getting judged by employers & more jail

Kim was arrested together with multiple others — the police brought in the gangsters in batches — and ended up doing his N-level exams in jail.

While in there, he repented, hoping to turn over a new leaf and make good of his life when he was finally released. He also felt a personal sense of accomplishment, having successfully passed his N-levels.

Filled with optimism, Kim applied for 10 jobs — chiefly positions in factories and warehouses as packers or various other labour work — wielding a special recommendation letter from the Yellow Ribbon Project, only to be laughed in his face.

"What if you beat my men? What if you recruit them?" he recalls being mockingly asked. Sadly, this drove him back to his gang, and roughly a year later, he was sentenced to his second term of jail for drug consumption.

After being released one and a half years later, having received a one-third discount for good behaviour, Kim was out for just three months before finding himself back in cuffs and in court, and then jail — this time, for extortion.

Photo via Singapore Prison Service Facebook page

Photo via Singapore Prison Service Facebook page

The sentence: five years. And nine strokes of the cane — the latter of which Kim says there was nothing he could have done to prepare himself adequately for.

Caning: a whole other ball game

What's caning like, you might ask? Kim describes the pain as being equivalent to getting hit by a lorry — he had three sets of three strokes, overlapping three times neatly with each additional stroke across the same area deepening the already initially seared-through skin across his buttocks.

The scars still remain today — faint, but still very much there, he says — but he remembers the humiliation of it all, even if one somehow sets the excruciating pain aside: the prisoners to be caned were lined up in a queue, and he watched the fellow before him get caned, while the person behind him observed his whipping.

He said during the time he was there, little was done to prevent infections either: immediately post caning and a quick swipe with iodine over the wounds.

The worst, and probably dumbest part, though?

His refusal to make a sound, or make any attempts to acknowledge the searing pain, the bleeding, the opening and ripping open of his wounds from movements and having to sit down right away — all because, he says, he was a Chinese gangster (apparently this stupidity did not extend to gangsters of other races) and could not afford to lose face for the gang he represented in prison.

Having to stay silent aggravated his agony. Kim relates that the morning after his caning, he was unable to decline an invitation to play basketball during yard time, and so had to pretend to be fine and dandy while his three-stroke-deep wounds were still painfully raw and bleeding.

It was so bad that fellow inmates called it out, but he had to dismissively wipe the blood away like it was perspiration and act like nothing was wrong.

Kim jokes and laughs at himself about all this now, but at the time, he admits, the bravado mattered. It made a difference between whether or not you became a target of verbal abuse and/or physical fights — which were both tiring and pointless.

Another unfortunate thing about caning, says Kim, is that while the first time is nightmarish, a criminal who has been caned before will have experienced the extent of fear of criminal punishment and so may not find it as much of a disincentive to commit repeat offences.

"After he knows what it's like, he will have nothing left to fear. He will know what to expect no matter how many strokes he gets — it's more of the same. No alcohol and women — apart from those two things, prison is really not that bad."

Fret not, though, this story gets better.

Finding himself through pottery, art, and the right people

Kim had completed a NITEC in electrical engineering, but remained uninspired while still in prison so he joined a pottery class — suddenly, his childhood dream of being an artist sparked a newfound clarity of purpose for him.

He learned some basics — biscuit burning at 950oC, followed by a second round of burning (after glaze is added) at 1200oC, and soon found a renewed solace and peace in moulding clay on a spinning plate.

Photo courtesy of Kim Whye Kee

Photo courtesy of Kim Whye Kee

And one fine day, a vase Kim had made (the one above, the smaller of two) was shown alongside work from other inmates at an exhibition within the prison complex. On Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam's prompting, established Singaporean painter Henri Chen KeZhan visited.

Chen tells Mothership he was asked which he would choose if he were to pick one he liked, and he happened to buy the one made by Kim — one that had a Chinese junk sailing across the top.

Kim explains the junk has to sail across the storms and mountains to reach the other side of the vase — symbolising the way he rediscovered his dream of being an artist through pottery, after years of being lost in a life of crime and gangsterism.

Chen didn't meet Kim at the time or have any inkling of who he was — but Kim jokes that Chen picked it because it must have been "the worst one", and therefore most in need of proper education. Chen corrects him with a laugh at this point, saying it had the most "potential".

But Chen subsequently requested to see Kim, and the latter found himself trundling up the hilly and very secluded Temenggong Road to a sprinkling of heritage black-and-white houses one afternoon. After observing him at work mending some broken pots outside, Chen decided Kim needed to enrol into art school.

"So I told him, I'll buy this, I'll make sure the ship sails."

Chen funded Kim's and three other ex-inmates' first academic year at LASALLE College of the Arts — the only art school willing to work with the Singapore Prisons.

Kim ended up being the only student seeing through his four years of education, majoring in sculpture — and yes, as we told you, he graduated with second-upper class honours in its bachelor degree of Fine Arts programme.

"I was really depressed when I was in NITEC. Even if you go to poly, after that you come out, you're a technician or an engineer.

I always say if I never met (Chen), it's either I'll become a factory worker or go back to the gang. It's so important to meet the right people. Even if I met other artists, I'm not sure things would have turned out the same way. Not many people can tolerate ex-offenders."

Giving back continuously, & journeying with boys-at-risk

Even while in school, Kim volunteered and gave back what he was receiving — he helped residents write appeal letters at DPM Tharman's Meet-the-People Sessions in Taman Jurong, still living in Boon Lay at the time, and on Tharman's prompting, got together a few fellow ex-inmates like lawyer Darren Tan and started an initiative they called "Beacon of Life".

Under the programme, Kim and Tan would seek out boys playing football at the void decks of HDB blocks — whom residents also reported had been abusing drugs — and befriend them. They played football with them, brought in an S.League player to train them properly, and also harnessed their own personal skills and pulled in friends to give them free tuition or lessons in numerous different skills.

At the time, DPM Tharman bankrolled most of the operation, said Kim, and the courses expanded into the Beacon of Life Academy to more formally serve more neglected youth at risk of entering gangs.

Today, the two Beacon of Life initiatives are now run by Tasek Jurong, a community foundation set up in the area that also funds their activities. Kim said all his own limited money from a factory woodworking job he had at the time — while still studying, yes — was going into Beacon of Life, and at some point he realised it wasn't sustainable.

Going pro

That's when Kim, on the prompting of his now-wife, started Qi Pottery — his very own business that he now works on full-time from their Buangkok Crescent HDB flat studio.

His initial teapots made about two years ago were large and artistically crafted, but after his first home-based exhibitions, tea-drinkers gave him feedback that they should actually be much smaller.Kim says he then studied under master potter Chua Soo Khim, returning to basic techniques like throwing to hone them better, and over the past two years has worked hard at improving his craft.

Photo by Jason Fan

Photo by Jason Fan

By the time we met him on Thursday afternoon, one day away from the opening of his maiden solo exhibition at the Temenggong — a space to nurture local and regional artists — Kim sounded a veritable expert in tea making and drinking, understanding the different types of clay, colours and their impact on taste — as well as the impact of the tea brewing on the teapots too.

His first solo exhibition will be attended by Home Affairs and Law Minister K Shanmugam, who shared a Facebook post about Kim's "remarkable journey".

With all these accomplishments under his belt, Kim does look back with wonder at how his life panned out from his days of getting beaten up in upper primary school.

Certainly, that junk has sailed across the stormy sea.

If you'd like to view or purchase Kim's work, his exhibition at the Temenggong (28 Temenggong Road, Singapore 098775) is open to the public this Saturday and Sunday, July 7 and 8, 2018, from 12 - 6pm. Admission is free.

Top photos by Jason Fan, photo of tea set and vase via Qi Pottery Facebook page

Content that keeps Mothership going

![]() Need some light reading while waiting for the next match to start? This almost true Singapore ghost story may help you with this.

Need some light reading while waiting for the next match to start? This almost true Singapore ghost story may help you with this.

![]() This letter to our writer's young self makes you think about your many regrets in life. Like posting embarrassing posts on Facebook that your RELATIVES saw.

This letter to our writer's young self makes you think about your many regrets in life. Like posting embarrassing posts on Facebook that your RELATIVES saw.

![]() Do you remember your days doing CIP? We attempted to do so without being awkward.

Do you remember your days doing CIP? We attempted to do so without being awkward.

![]() Have you ever wondered what it's like to be deaf inclusive? This is how a group of youths did it.

Have you ever wondered what it's like to be deaf inclusive? This is how a group of youths did it.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.