At the time of Singapore's founding in 1819, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles had a key objective -- to establish the settlement as a free port in order to compete with other regional under the control of the Dutch.

Part of achieving this objective involved making Singapore as attractive as possible for merchants and their businesses, as seen from the Raffles Town Plan which allocated land to different segments of society in order to facilitate the ease of trade.

Raffles also sent out invitations to different regional communities, encouraging their merchants to settle in Singapore.

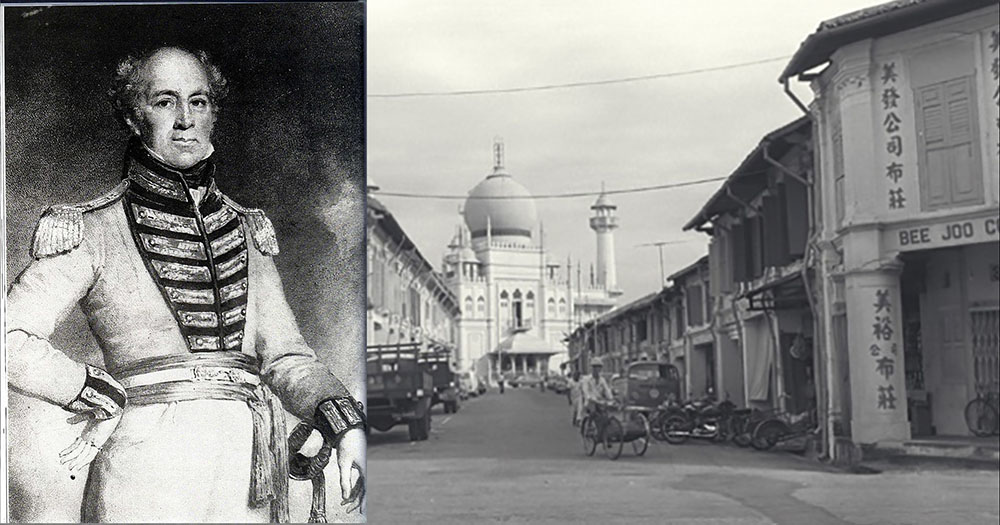

Yet, if it was Raffles who first invited them to set up shop in Singapore, it was the presence of a different figure who gave them enough confidence to actually do so -- Raffles' second-in-command, British Resident William Farquhar.

William Farquhar's efforts

According to Australian writer Nadia Wright’s book, William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping out from Raffles’ Shadow, Farquhar had already acquired a reputation as the "Rajah of Malacca" amongst the Arabs, Indians, Chinese, Malays and Europeans, with his successful turnaround of Malacca from years of losses in trading.

In fact, when news of Farquhar's departure for Singapore to take over Raffles' administration spread in the early 1820s, more than 5,000 merchants departed Malacca to settle in Singapore instead.

Farquhar's success stemmed greatly from his close cooperation with the local population, utilising his expert knowledge in Malay culture and politics, which had been developed over 25 years.

As Wright's book details, Farquhar made sure Singapore was as attractive as possible to local traders. He permitted gambling and opium dens, provided a license was paid, and used the money from the licensing fees to fund the Singapore police.

Farquhar also worked as a cultural bridge between the British and the other populations of Southeast Asia, often explaining to the British in Malacca why certain actions would upset the Malay population and suggesting alternative courses.

All of these helped to inspire confidence amongst the Asian merchants about his administration of Singapore.

In contrast, Raffles departed Singapore a few months after his arrival in 1819 for his base in Sumatra.

As Wright's book sums up, he “left Farquhar understaffed, underfunded and under-stocked, having issued hopelessly impractical orders to be carried out in his absence”.

In fact, as some historians note, Raffles was present in Singapore for a total of less than 10 months, on only three instances over five years -- January to February 1819, May to June 1819, and October 1822 to June 1823.

His role in the daily administration of Singapore was minimal relative to Farquhar.

[related_story]

The Arabs -- outsized contributions relative to their size

One community that Raffles had a particularly keen interest in inviting were the Arabs.

This was because many of the Arabs already had established networks and influence in the Indo-Malay Archipelago prior to Singapore's founding.

The number of Arab merchants who decided to come to Singapore were small compared to other Asian populations.

By 1824, the first census taken showed that only 15 of Kampong Glam's 9,652 residents were Arab.

As a point of comparison, 3,178 of the Kampong Glam residents were Chinese, as highlighted by Jane Perkins in her book, Kampong Glam: Spirit of a Community.

But the size of their presence did not stop them from making immense contributions to the community.

Mostly hailing from the Hadhramaut region in Yemen, many of them were successful businessmen in a variety of industries such as retail, wholesale, production, and particularly, real estate.

The Arabs also played a key role in building up Singapore's Muslim community with the custom of wakaf, where they dedicated land and property for religious or charitable purposes, and as religious teachers.

These contributions have left a deep imprint in Kampong Glam and in areas around the central district, both in terms of business and religion.

Community Contributions

Thanks to their astute land purchases, by the 1930s, the rise in land prices meant that the Arabs had become the largest landowners in Singapore along with the Jewish community.

Prior to the Land Acquisition Act of 1967, the Alsagoffs, for instance, owned the Raffles Hotel and the land it sat on, while the Alkaffs built Singapore’s first indoor shopping centre, the Arcade.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="740"] Source: YourSingapore[/caption]

Source: YourSingapore[/caption]

The Arabs also owned whole stretches of properties in Kampong Glam. Here was where a range of businesses belonging to different ethnic groups came to set up their livelihood.

There was the historically large Javanese population who operated food stalls, eating houses, flower stalls, and sold fruit and Javanese leaf cigarettes. The Arabs themselves traded in dates, rubber, perfume oils, agarwood and honey.

There were also the Indian businessmen who owned basketry shops, which encompassed a range of products such as wicker baskets, cane, bamboo, straw works, rattan, and handicrafts.

Basketry was a particularly important industry for both recreation and livelihood, due to the use of rattan baskets in a multitude of areas, from baby cradles to chairs, and from grocery baskets to hawkers peddling their wares.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Source: National Archives of Singapore

In terms of religion, the contributions of the Arab community mainly came from two areas -- their dominance in the Muslim pilgrimage industry during the colonial era and their custom of wakaf.

For the pilgrimage industry, Arab brokers known as Shaylehs would recruit potential pilgrims from the region, help arrange for their passage through shipping agents, and escort them to Mecca in Saudi Arabia.

Once there, the pilgrims would be handed over to local brokers for the rest of the journey.

This made Singapore a regional centre for Muslim pilgrims on their way to Mecca, with Arab-owned shipping companies such as the Alsagoff Singapore Steamship Company providing the transport.

One such recorded instance was in 1874, where the Alsagoff Singapore Steamship Company transported 3,476 pilgrims to Mecca, with around 2250 pilgrims coming from the Netherlands East Indies.

In the second area of wakaf -- the custom of designating a physical object for religious or charitable purposes -- many of the Arab merchants donated entire pieces of land and properties, which benefited the Muslim community in the form of schools, hospitals, and religious institutions.

The first recorded instance of wakaf in Singapore was the endowment of the Omar Mosque in 1820 by Arab businessman Syed Omar bin Ali Aljunied.

Later, further wakafs from Aljunied would include the Bencoolen Mosque and Jalan Kubor Cemetery along Victoria Street for Muslim burials. Such contributions were how the donor families came to gain much prestige in their communities.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="1200"] Source: Wikipedia[/caption]

Source: Wikipedia[/caption]

Explore this part of history for yourself

Presently, some of the businesses set up by the original Arab merchants in the past are still thriving today.

Shops such as Aljunied Brothers at 95 Arab Street, and Aidid Trading Co. at 74 Bussorah Street, which were established in 1966 and 1967 respectively, sell a variety of products ranging from agarwood to perfume oils and Hadhrami honey.

Many of the products are imported from Hadhramaut itself.

As for the basketry shops set up by the Indian business community, only a single shop currently remains -- Rishi Handicrafts on 58 Arab Street.

As important as the basketry industry used to be, the invention and subsequent mass production of cheaper materials such as plastics have caused the industry to greatly dwindle over time.

Source: Aliwal Arts Centre

Source: Aliwal Arts Centre

The fact that it is a vanishing trade has not gone unnoticed however.

Coming up this weekend, the Aliwal Arts Night Crawl, on July 28, will look at the vanishing art of basketry, featuring both traditional and contemporary art forms to reflect the identity of Kampong Glam and a chance to listen to the story of Rishi Handicrafts.

You can also learn a new skill at their themed workshops, gain insights on an Open Studio Tour (yes, you’ll get to tour Aliwal artists’ studios), catch a performance or two, and have fun with kid-friendly interactive elements.

Where / When to go

Date: Saturday, 28 Jul, 2018

Time: 5pm till late

Location: Aliwal Street will be closed off from 5pm till late, with two stages and an interactive zone. Look out for activities lurking in Sultan Gate Park, Malay Heritage Centre, and several retail establishments in the neighbourhood too.

This sponsored article by Aliwal Arts Centre made the writer think about updating social studies textbooks.

Top image by One Kampong Gelam

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.