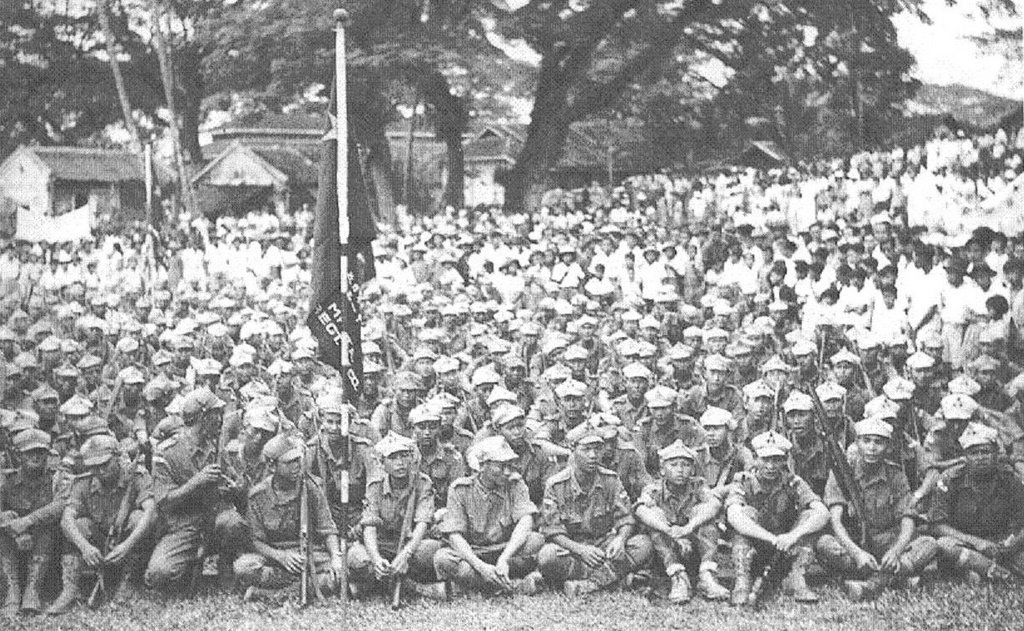

On June 24, 1948, a State of Emergency was declared in Singapore.

This occurred one week after an Emergency was declared in Malaya, as a response to the ongoing guerrilla campaign waged by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP).

For the late leader of the MCP, Chin Peng, the turn to armed revolt was the result of the passing of a law under the newly-created Federation of Malaya, which restricted union powers and deprived the MCP of the right to lead the trade union.

Source: HNMUN Malayan-JCC

Source: HNMUN Malayan-JCC

As Chin Peng recounted in his own account of events, he felt the "inevitable next step" would be "the outright banning of our party".

In his view, it was the "vested interests, like plantation owners' organisations or tin miners' groups", which had led to this piece of legislation being passed.

It was also further proof that "the local man or woman in the street had no influence at all".

Accordingly, the decision was made within the MCP that "there was no option... but to wage war for our principles."

Effects on Singapore

Although much of the fighting was waged in Malaya, Singapore keenly felt its spillover effect.

As the late Lee Kuan Yew mentioned in his memoirs, the MCP had been fomenting "labour unrest and social tensions... and by June 1948, Communists had started shooting and killing British rubber planters upcountry."

Additionally, the MCP were "winning many recruits from among the Chinese-educated majority in Singapore, who had been impressed by reports of Communist China's progress", with even some of the the most idealistic "English-educated intelligentsia" succumbing "to the appeal communism had for peoples fighting colonialism."

As Lee saw it, "the militancy was contagious."

What's more, the State of Emergency would have a profound impact on shaping the political landscape of Singapore for the years to come.

Attacks on British authorities and interests

The MCP launched various acts of violence against the British in Singapore and often encouraged their supporters to do the same.

Some of their efforts in Singapore included the attempted assassination of Singapore's postwar British governor, Franklin Charles Gimson, on April 28, 1950, with a hurled hand grenade at the now-demolished Gay World, and various acts of arson and murder targeted at British interests.

Instances of assaults on the police were also recorded.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Source: National Archives of Singapore

The MCP was also proactive in infiltrating trade unions to organise strikes in industries where British businesses were involved, subsuming the grievances of various labourers to their cause, especially where rubber plantations were concerned.

Essentially, anything that was an institution of the British was to be targeted.

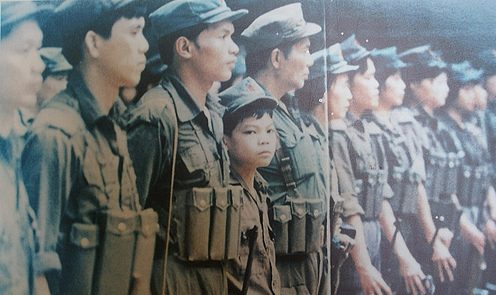

Firing up the Chinese-educated population

Of far greater impact, however, was the MCP's use of their members to "foment feelings against authority among the workers, the rural dwellers in the countryside... and Chinese middle school students," as Lee further noted in his memoirs.

The conditions for Communist infiltration were ripe.

Lee saw that the the Chinese-educated "had no place or role to play in the official life of the colony".

This created a lack of economic opportunity and sense of dispossession, "which turned their schools into breeding grounds for the communists".

It also allowed the MCP to expand their base in Singapore greatly.

The tactics that the MCP employed to do so also left a deep impression on Lee, convincing him that they were "superb stage managers of the mass rallies by the pro-communists".

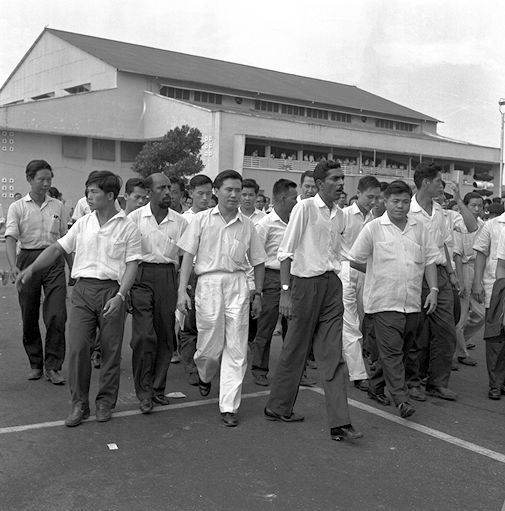

Stage-managed impressions

One tactic that Lee observed in particular was the use of cheerleaders to stage prolonged applause for speakers who attacked the State of Emergency and jeers for those who did not follow the MCP's official line.

The overall effect was to amplify the message of the MCP.

And given that even some of the English-educated population, despite their favoured treatment by the British government, were starting to support the communists, Lee decided that if the English-educated were not mobilised "into an effective political movement, the MCP would be the ultimate gainer".

Thus, was born one of Lee's impetuses for the creation of the People's Action Party.

It would be a party that would have the goal of creating "a democratic, non-communist, socialist Malaya", as Lee put in his own words.

Formation of the PAP

Even so, Lee realised that if the PAP were to succeed at all, it would still need the support of the Chinese-educated in order to claim that it represented the people.

And so contact was made with some of the Chinese trade union leaders, despite their communist leanings, to enlist their support.

The year was 1954.

Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan of the Singapore Bus Workers' Union replied to Lee's outreach.

Lim Chin Siong with Lee Kuan Yew. Source: Flickr

Lim Chin Siong with Lee Kuan Yew. Source: Flickr

They went to 38 Oxley Road to meet with Lee.

His initial impression of them was favourable. Lee found them determined, selfless and hardworking, and he was hopeful they would be won over.

Fong Swee Suan speaking at a rally. Source: National Archives of Singapore

Fong Swee Suan speaking at a rally. Source: National Archives of Singapore

Lee explained to Lim and Fong that he intended to form a party:

"... to represent the workers and the dispossessed, especially among the Chinese-educated... to gain a significant number of seats so as to show up the rottenness of the system and the present political parties, and to build up for the next round."

After some deliberation, and a request by Lim to be excluded as one of the convenors of the party out of fear that his police record could harm the party's status, Lim and Fong became two of the PAP's founding members with its establishment on Nov. 21, 1954.

[related_story]

LKY's relationship with Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan

In 1955, the Legislative Assembly general election was slated to be held on April 2 and the PAP ran on a platform calling for the independence of Singapore via merger with the Federation of Malaya and for the Emergency in Singapore to be abolished.

During the period of campaigning leading up to election, Lee noted the oratorical prowess of Lim, with the attraction he drew from women in the trade unions, and his themes of "the downtrodden workers, the wicked imperialists, the Emergency Regulations that suppressed the rights of the masses, free speech and free association".

Source: Flickr

Source: Flickr

Combined with the manipulation of the rallies by the communists, as mentioned above, and the support from the Chinese-educated, the PAP's platform was solidified.

Lee had reservations however, about "whom the unions and the Chinese students were really campaigning for through their biased behaviour over canvassing and cars".

Lee would win the Tanjong Pagar constituency, while Lim would go on to win the Bukit Timah constituency for the PAP.

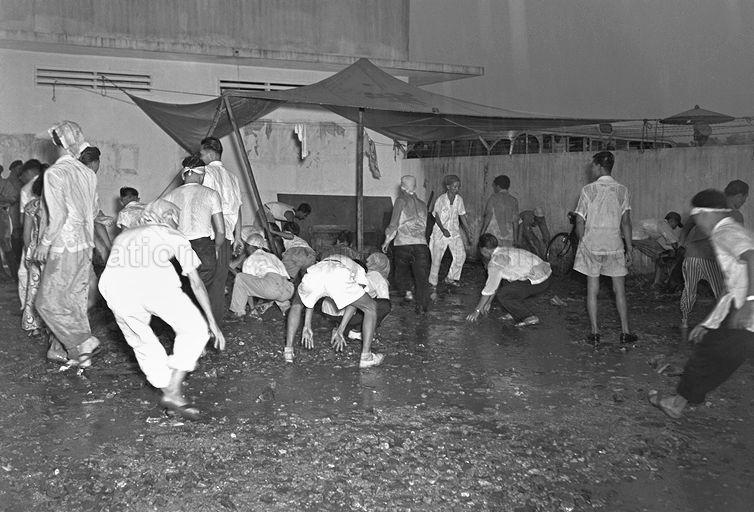

Unfortunately, the next month saw the Hock Lee Bus Riots, where a strike organised by Fong eventually escalated into a riot on May 12, which left four people dead and 31 people injured.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Source: National Archives of Singapore

In its wake, the British authorities squarely placed the blame on the trade union leaders and Chinese students, and responded by closing three Chinese schools.

The students responded with sit-ins at the schools.

Lim and Fong organised the trade unions in support of the students with marches through town that, according to Lee, involved "stone-throwing and attacks on cars".

As such, Lim and Fong were blamed by the British for the riots.

In particular, Fong was blamed as the chief instigator because of his role in organising the strike preceding the riots.

He was detained for 45 days under Emergency regulations, starting on June 11 and upon release, denied he was a communist.

For Lee, the actions of Lim and Fong convinced him that their course would end in "political disaster" for the PAP.

Laying the groundwork for the Internal Security Act (ISA)

In any case, the Hock Lee Bus Riots came to have a significant effect on the Emergency Regulations.

Chief Minister David Marshall, whose party, the Labour Front, had come to head the government at that time, reviewed the Emergency Regulations and replaced them with The Preservation of Public Security Ordinance on October 18, 1955, after due parliamentary process.

Under the new law, an individual could be detained by the government for up to two years if he or she was deemed as a threat to Singapore's national security.

This law would eventually come into sharper focus with Malaya's own enactment of a similar law under the name of the Internal Security Act at the end of the Malayan Emergency in 1960.

In 1963, during Merger, it was extended to Singapore to include The Preservation of Public Security Ordinance as well.

Much of its wording has remained unchanged since independence.

A seminal period in Singaporean history

For better or worse, the Emergency in Singapore saw the galvanising of the Chinese-educated population against the British, the formation of the PAP, the sowing of the seeds for Lee's eventual fallout with the PAP's left-wing members and the basis of the ISA being laid.

The legacies this tumultuous period of Singapore has produced is still being debated today -- if the recent cross examination of Singaporean historian Thum Ping Tjin by Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam on the final day of the public hearing on online falsehoods is anything to go by.

Top image from http://photos1.blogger.com

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.