One thing Singaporeans never hear the end of: How Singapore built up its water resilience for survival.

Over the years, Singapore has been developing and innovating its water technology, making sure to collect every drop of water, reusing water endlessly and desalinating seawater.

It has come some way since even before nationhood, where Singapore was, and to an extent, still heavily dependent on Malaysia's freshwater.

And with this ability, Singapore has harnessed water not only for survival but even as a diplomatic tool.

Buy and then sell water to Malaysia

Singapore is innovating to become more robust to avoid over-reliance on one major source of water.

And one major source is Malaysia.

Singapore has signed four water contracts with Malaysia in 1927, 1961, 1962, and 1990.

These water agreements are meant to provide up to half of Singapore's water demand, since Singapore's natural catchment isn't big enough.

The first two agreements have expired.

If you're interested, here's the 1962 Water Agreement (also known as the Johor River Water Agreement) signed between the City Council of the State of Singapore and the State of Johor:

Here is the 1990 Water Agreement, which was signed between Singapore's Public Utilities Board (PUB) and the State of Johor:

Under the 1962 and 1990 agreements, this was what Singapore could do:

- Draw up to 250 million gallons per day from the Johor River.

- Build a dam to regulate the flow of freshwater in the Johor River and creating the Linggiu Reservoir, from which we draw water.

- Buy treated water generated from the dam from Johor above the 250 million gallon daily limit.

In return, Singapore pays rent for the land it uses for drawing water, and covers the costs of building and maintaining the dam. It also sells treated water to Johor at 50 sen per 1000 gallons.

These two legally-binding agreements will only expire in 2061, but that hasn't stopped Malaysia from trying to change the price of raw water it supplies to Singapore.

Water as negotiating card

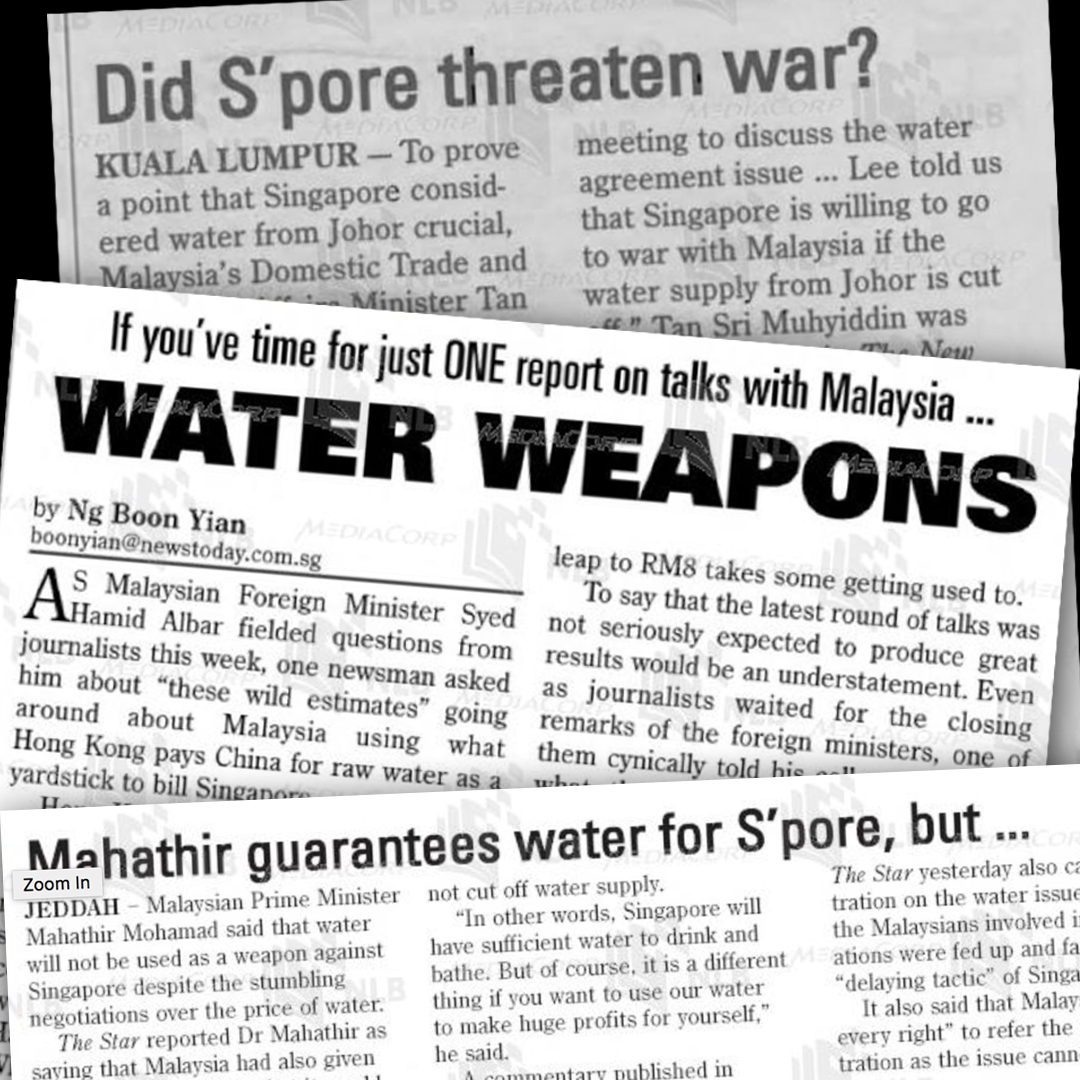

Throughout the 1980s and 2000s, Malaysia often issued veiled threats to cut off its water supply to Singapore.

Things got pretty ugly in 2002 when talks between the two governments regarding a bilateral package deal escalated into a war of words about the pricing of water.

While Malaysia never acted on those threats, it was a very clear example that Singapore did not have the upper hand, and had to depend on the sanctity of international agreements in water negotiations.

Singapore subsequently resolved to cut down its dependence on Malaysia's freshwater by developing her own water.

This is now most notably done by desalinating seawater and recycling waste water (NEWater).

The Singapore government is set to be completely independent of Malaysia's water supply by 2061.

Water expertise and humanitarian efforts

Having growing confidence in Singapore's self-sufficiency when it comes to water, the water technology developed and experience in urban water management has also allowed the country to become an international leader in water matters.

This is an increasingly important matter today when water security is a global issue.

This sort of expertise and leadership enables Singapore to engage in what is called "niche diplomacy", which is how a country can use its domain expertise to exercise influence.

Singapore does this by sharing water management expertise and offering humanitarian help, often to emerging countries that do not yet have a stable water management system in place.

Singapore's public service experience

The PUB's Technology and Water Quality Office is currently a designated World Health Organisation (WHO) Collaborating Centre for water management.

It promotes "safe management of drinking-water and integrated urban water management".

This is done by sharing best practices, conducting training for WHO members states, and leading public health strategies in the Western Pacific region and other regions in the world.

Singapore has been able to lend her expertise in water management to countries such as India in 2012, and Mauritius in 2011, to treat waste water and develop systems that provide potable water.

These were managed by the Singapore Cooperation Enterprise (SCE), which helps foreign governments meet their development objectives by drawing on Singapore's public service experience.

Humanitarian assistance

More importantly, Singapore shares her water expertise in the form of humanitarian assistance.

In 2017, the Singapore Red Cross provided water filtration equipment and other supplies to Marawi when it was under siege by pro-Islamic State fighters.

Singapore also provided water monitoring equipment and filtration sets to Cambodia and Thailand when they were hit by devastating floods in 2011.

In the longer term, Singapore is providing bio-sand filters to rural areas in Cambodia to help them access clean water and reduce the incidence of water-bourne diseases.

All these water efforts have enabled Singapore to strengthen diplomatic relations with other countries and her position on the global stage.

These sorts of niche expertise were developed as a result of the country's vulnerability in the first place, namely, water insecurity and scarcity.

Top image from Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen's Facebook page depicts SAF humanitarian efforts to Marawi

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.