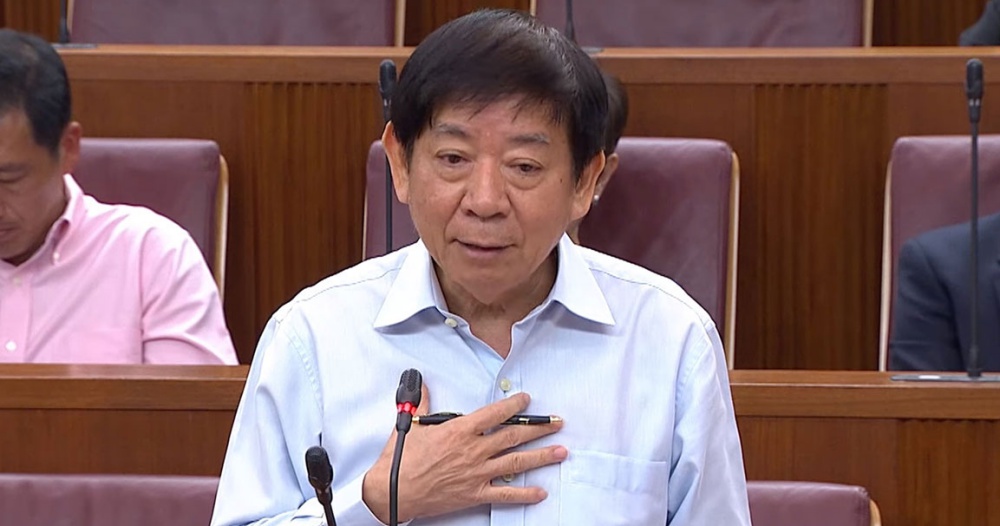

Public transport commuters in Singapore are angry at Transport Minister Khaw Boon Wan again.

What did Khaw say?

This was after Khaw said in Parliament on May 18 on the final day of the debate on the President's Address that linking reliability to transport fares directly could worsen the situation:

"When a system is very unreliable, in fact, that is the time to pump in more resources... And if you punish them through reduced fares, you are withdrawing resources from the operators, and you will be doing exactly the opposite."

This was reported by Channel News Asia.

Why did he say that?

He was responding to parliamentary questions from Workers' Party Non-Constituency MP Dennis Tan and Nee Soon GRC MP Lee Bee Wah on whether rail reliability and service standards can be captured in the new fare formula.

In other words, Khaw meant that fares should not go down if public transport becomes unreliable.

Because unreliability means there are problems, and money is needed to fix these problems.

Reducing fares exacerbates the problems.

These questions pertain to the new transport fare formula that will kick in by end-2018.

The new transport fare formula will take into account a whole bunch of stuff that includes price index, operator productivity, and the capacity of public transport supply to serve demand.

However, rail reliability and service do not factor in the new fare equation.

What is the latest arrangement?

At present, public transport operators in Singapore are no longer responsible for public transport infrastructure or capacity.

The government owns all bus assets and operators bid to run services.

With the Rail Financing Framework, for example, SMRT will pass the buck: Infrastructure concerns are under the purview of the Land Transport Authority.

Operators are now in charge of maintaining the assets (trains, stations, interchanges etc.) and focus on providing reliable services.

Khaw might be right about something

Khaw's argument is not without merit.

Under the new Rail Financing Framework, licensed operators have to abide by certain service and reliability standards set out by the LTA.

Linking transport reliability to fares is another extra layer of regulation which can be unfair to operators.

What can commuters feel iffy about?

Instead, commuters might be iffy about Khaw using himself as a guarantee.

Khaw insisted in Parliament that he will deal directly with operators when it comes to rail and service reliability "through the sort of focus and pressure" he is known to exert.

This is pretty abnormal for a government that uses formal regulations when dealing with entities and matters with consequential outcomes.

And this is despite Khaw saying that he has made rail reliability "my priority and I will see to it that it happens, whether or not this is included in the fare formula".

Despite this assurance, the question commuters will have is: What will happen if Khaw is personally not around anymore?

Then how do commuters ensure Khaw's priority can be transferred to the next transport minister?

How to reassess Khaw's meaning?

However, for a more charitable reading of what Khaw said in Parliament, you are advised to read The Straits Times coverage of this issue.

ST reported that the service factor is indirectly included in transport fare formula.

This is the rationale:

For instance, "if we do not expand the rail network but demand grows, as it happened a few years back, that means resulting in crowded trains", the Public Transport Council (PTC) "will be asking for a reduction in fares".

But "if things improve through more comfortable rides but costs go up... there may be a need for fare adjustments," he told the House.

[related_story]

Where does money come from?

Once again, even though this has been reiterated many times before, at the end of the day, this is a resource allocation game.

Bear in mind that the Public Transport Council is responsible for setting fares.

It is their duty to balance the interests of taxpayers and commuters. The point is for the money to eventually come from somewhere to keep pushing for Singapore's public transport system to be world class. And sustainable.

Any funding to make Singapore's public transport First World would, therefore, have to come from "either taxpayers through subsidies or commuters through fares".

Commuters, however, are also quick to note that, yes, it is agreeable that money has to come from somewhere, but SMRT, even at its worst, was turning in after-tax profits of S$26 million and S$81 million in 2017 and 2016.

Perhaps the next phase of the conversation is to show how ploughing all that back might still not be enough.

Only then, public transport commuters might be more convinced.

And less angry.

Top image via YouTube

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.