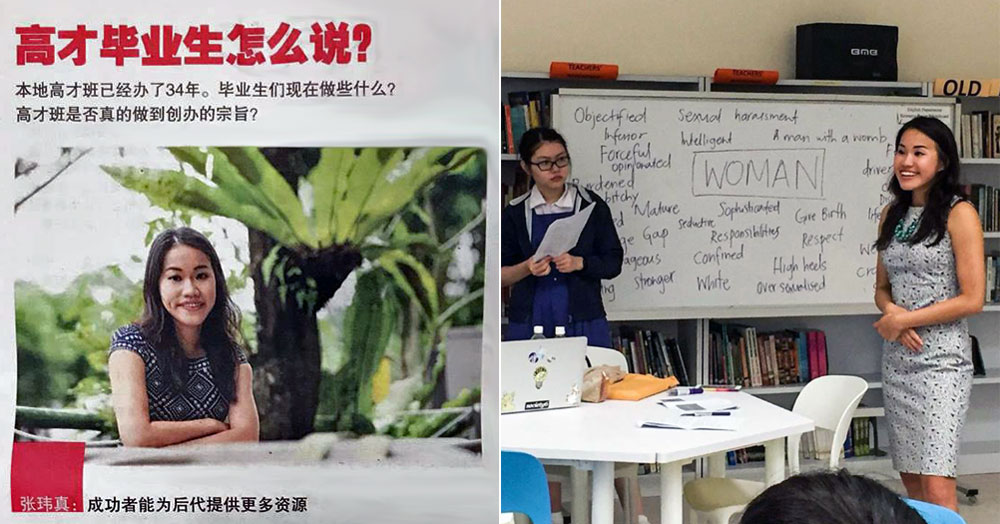

The Gifted Education Programme (better known by its initials GEP) has been around for a good three and a half decades now.

According to the information pages on the Ministry of Education's website, it exists to cater to the "intellectually gifted", and for a small country, doing so is "to the advantage of the nation":

Screenshot from MOE website

Screenshot from MOE website

And depending on who you are or where you are in life or placed in society, you'll either see it as a great thing to aspire to, or abhor it as heaping unnecessary stress on the already-intense Singapore primary education system.

But because it caters to just one per cent of any given batch of students each year, people who know it well enough — those who have been through it (sometimes referred to as GEPers) — to talk about it are few and far between, so we don't hear about it as often.

It so happens lawyer-poet Amanda Chong is one of these batches of academic "super-elite", though, and on Monday, April 30, she took to Facebook to share an interview she did with a Chinese newspaper that had asked her for her thoughts on the GEP.

Why it should be scrapped

Chong shared in a post that, as she said in the interview, her view is that the GEP should be discontinued since it has evolved into yet "another badge of elitism" — to her, the many places that offer "GEP test preparation" for middle-class children whose parents are hoping they can game the programme's entry tests standing testament to this fact.

She raises a few reasons for her view:

- Access to the GEP hinges on more than mere smarts.

She points out that access to opportunities, coaching and even the prior exposure to IQ test-style question format can pit a perhaps otherwise-average but wealthy kid above a natural genius who simply hasn't had the access to tuition or prior coaching.

In one instance, Chong relates the story of a child she coached as part of the reading programme she co-founded who wasn't able to go for the GEP test because of health issues and work commitments his parents had as full-time hawker stall assistants.

[related_story]

- School syllabi have evolved to focusing more on problem-solving and creativity.

This, she argues, is more suited to the needs of brighter students, whom she describes as "would-be GEP kids", and conversely more detrimental to those who might not inherently possess the smarts or the money to make up for that lack.

Besides, Chong notes, the biggest thing being in GEP taught her is a) that she isn't the smartest person in the room, and b) book smarts don't matter all that much in the larger scheme of things anyway — one's character does.

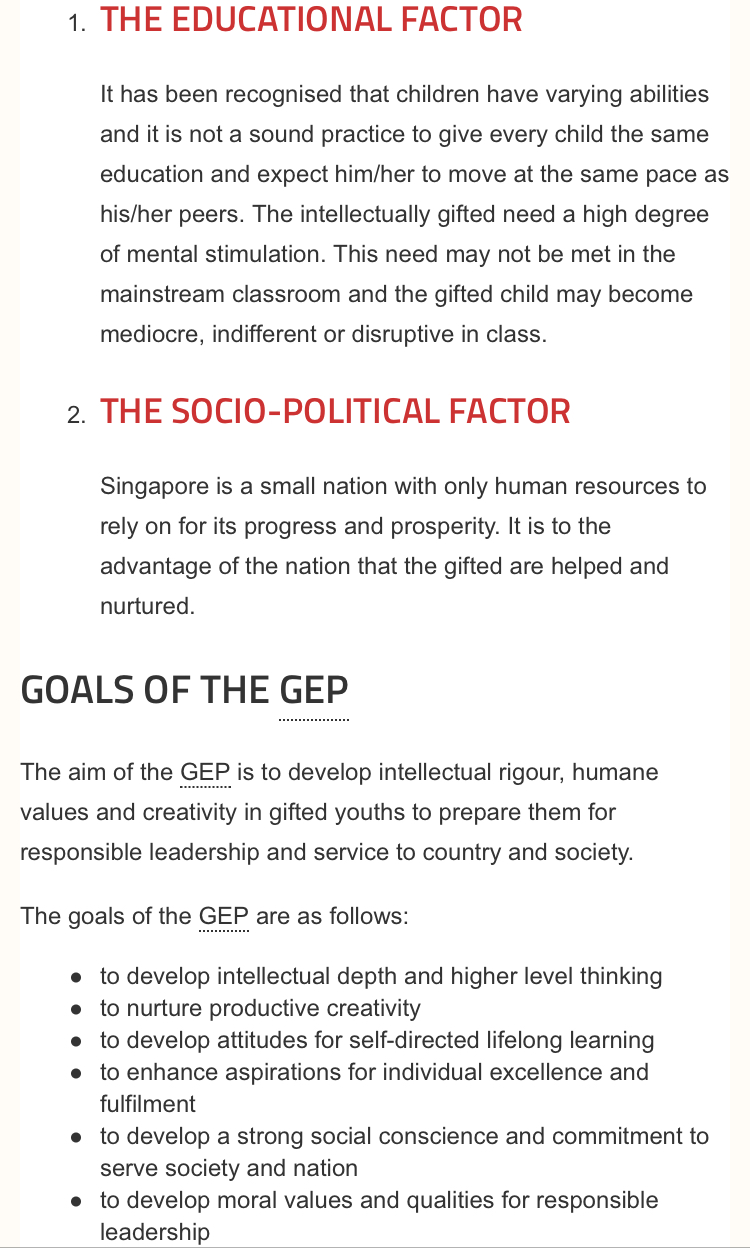

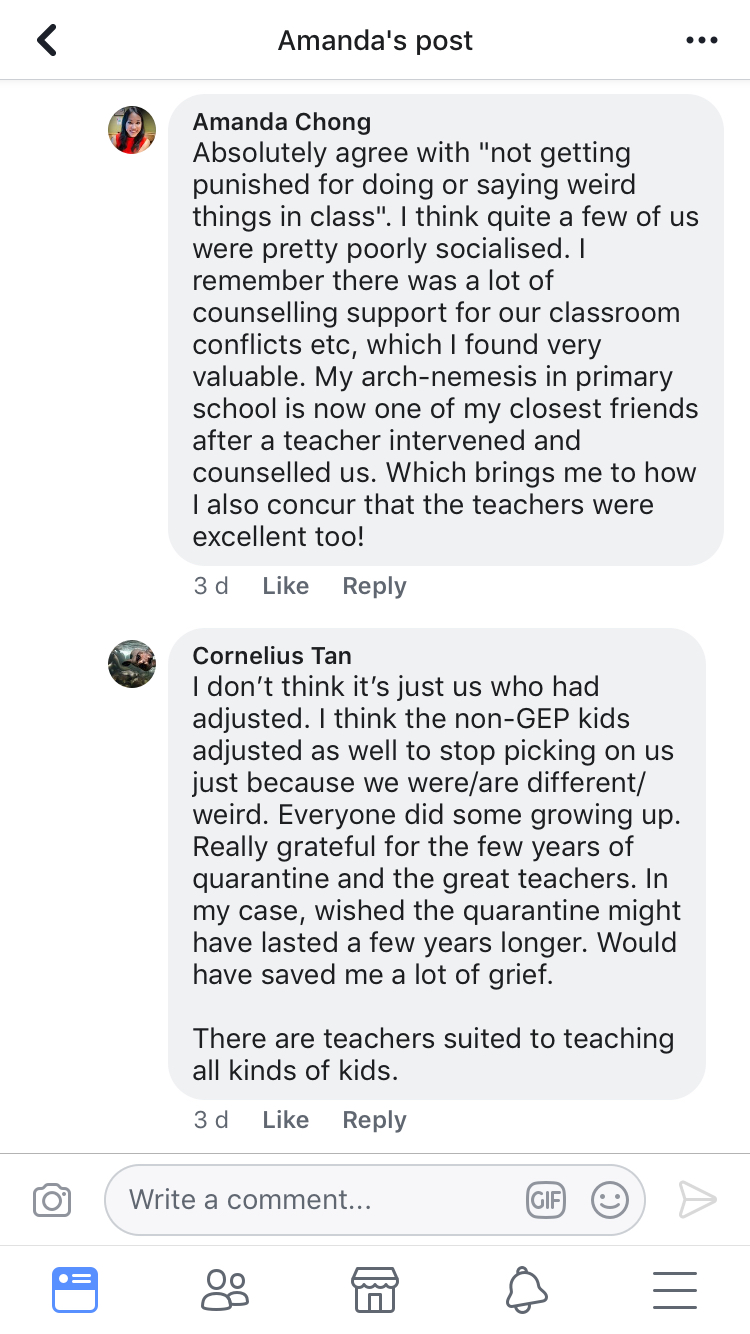

GEPers respond

Interestingly, Chong's post attracted responses from a good number of GEPers. Some of them praised the virtues of the programme, sharing how it benefited their lives:

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

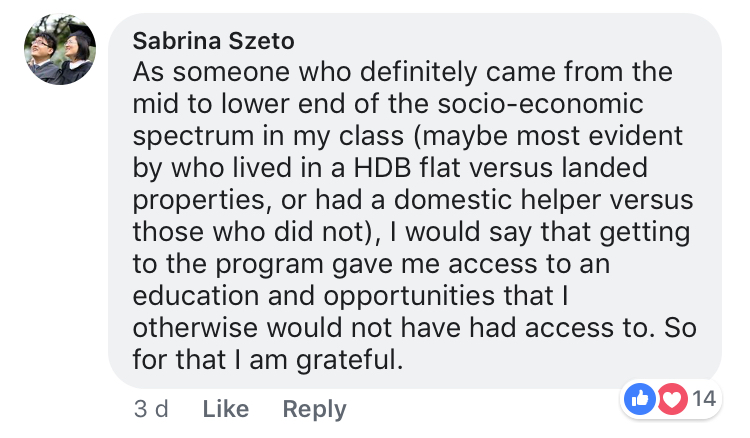

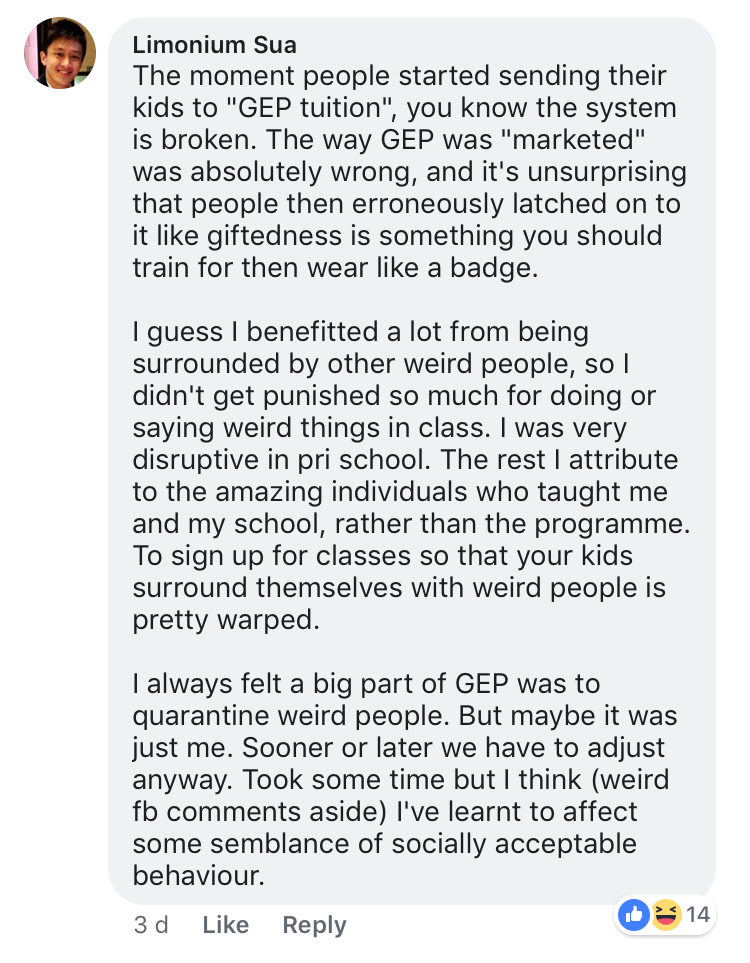

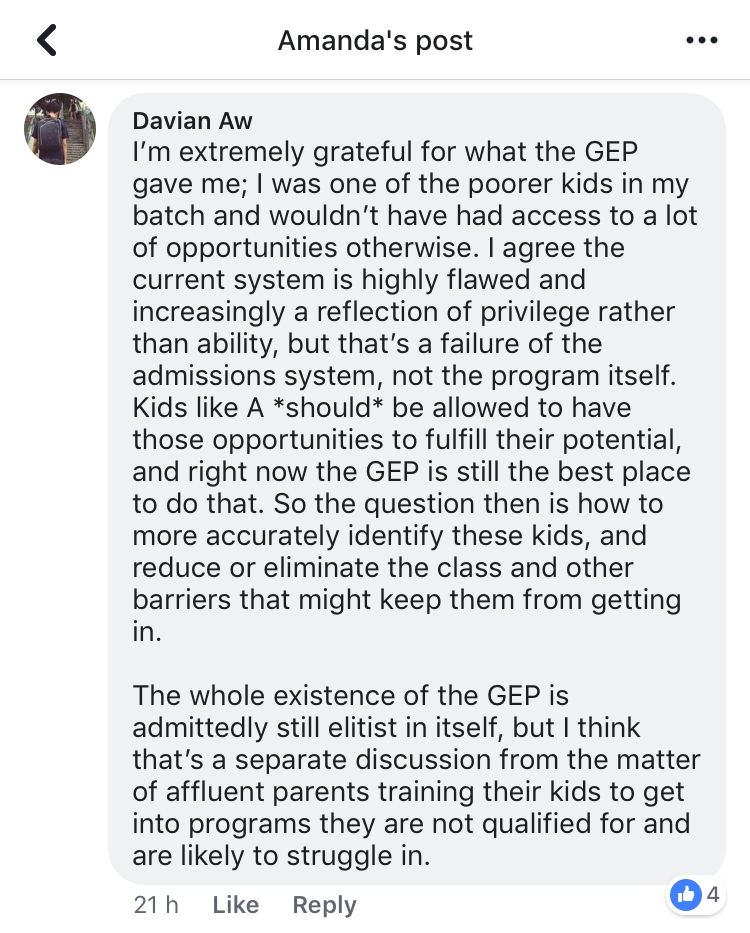

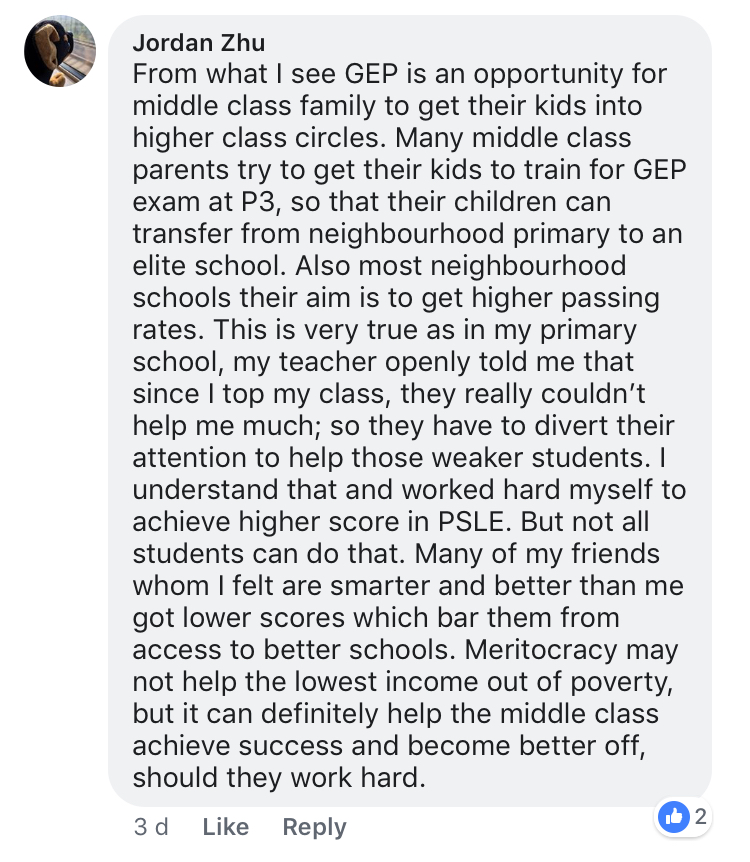

But some spoke more strongly about the importance of preserving the programme, highlighting that it was the issue of making sure brilliant kids from difficult circumstances or backgrounds still manage to get in rather than it in itself being flawed:

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot from Amanda Chong's post

Screenshot from Amanda Chong's post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

Screenshot via Amanda Chong's Facebook post

It's about the access and equal opportunity for all kids

Reading Chong's post on its own may make you see her as resentful of the GEP and what it's done to parents who now try to game its entry tests in a bid to call their own children "gifted".

But she shares she has in a previous talk extolled its virtues and lauded the teachers on the programme from her time in it:

Speaking to Mothership, Chong says to her, as reflected in what she eventually said in her post, the more pressing need is to address inherent inequality in Singapore's education system as opposed to whether GEP should be scrapped or not."Nowadays children are expected to enter primary 1 with a level of literacy in both English and their mother tongue. So many of the less privileged children’s first experience of the education system is already one of feeling like a failure. We have seen children we work with feeling demoralised or dispirited because they are behind their classmates from the first day of primary 1, whereas I feel the education system has progressed to catering well to high ability learners."

And, she feels, in an ideal society, our education system would be able to cater to all learners — less-privileged and higher ability children — with ongoing efforts to subsidise early childhood education a step in the right direction to begin with.

At the end of the day, Chong says, if accessibility to the GEP can be improved, the programme could still be a force for good.

You can read Chong's post in full here:

Top photo courtesy of Amanda Chong for the ReadAble project

An exclusive deal for Mothership readers:

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.