Operation Coldstore is a controversial piece of Singapore history.

How it happened is not as controversial as why it happened, details of which will continue to be argued over for a long time to come.

We break down what we know:

What is Operation Coldstore?

Operation Coldstore was a covert security operation which culminated in the arrest of over 100 people on Feb. 2, 1963.

The government maintains that those arrested were communist sympathisers plotting to subvert the government.

The mainstream understanding of events is that the operation broke the underground communist network that had been running since World War II.

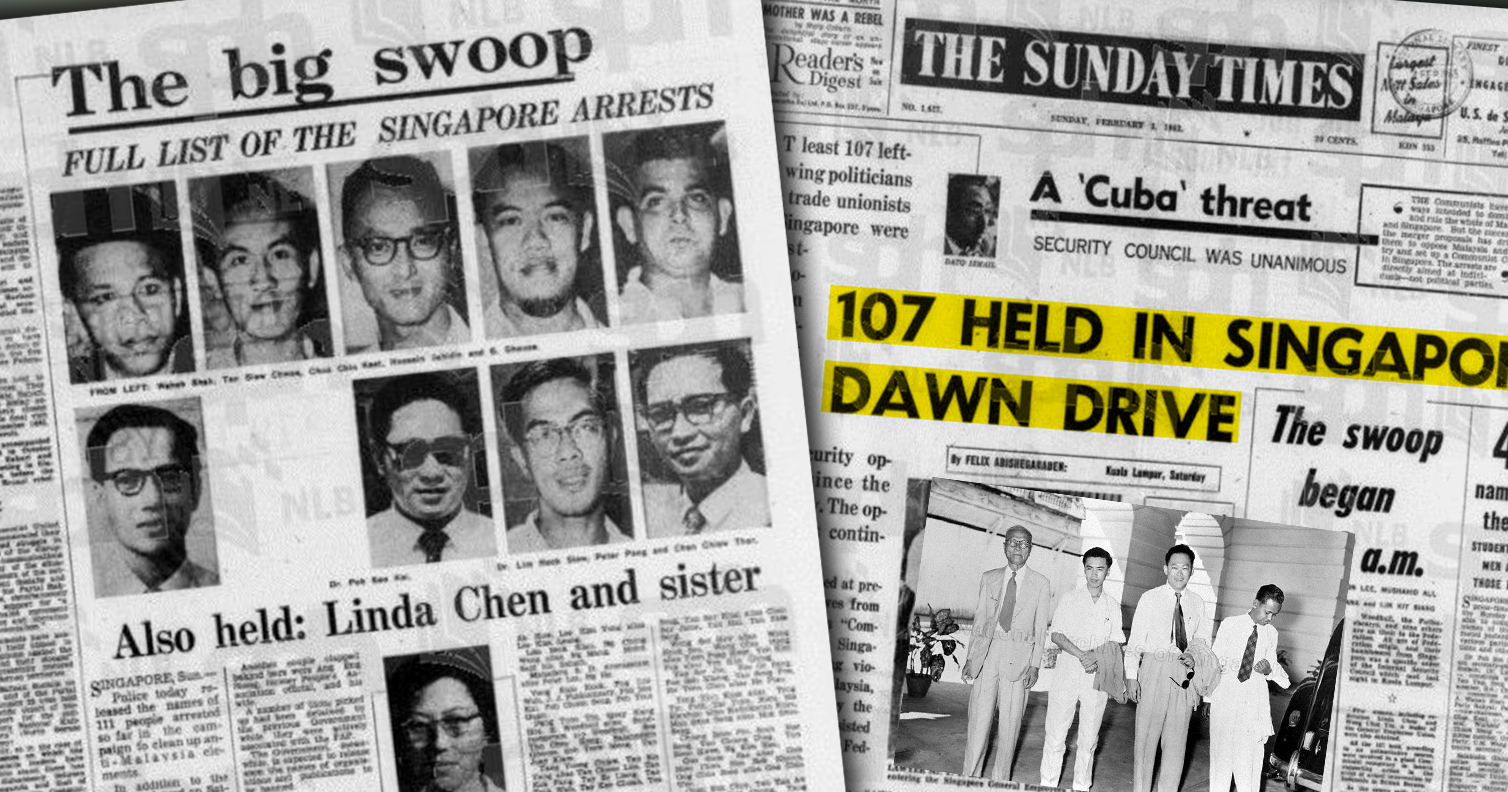

February 3 1963 headlines.

February 3 1963 headlines.

Those arrested included Lim Chin Siong, Fong Swee Suan, James Puthucheary, Dominic Puthucheary, Poh Soo Kai, and Lim Hock Siew. They were detained without trial.

Many of the detainees were politicians mostly from Barisan Socialis, the faction that split from the People's Action Party.

While we do know that the number of arrests made ran into the hundreds, the exact number is debatable.

But to really understand Operation Coldstore, there is a need to first understand it as a product of a particular time and place.

Post-war exhaustion

Britain emerged from World War II largely exhausted and bankrupt.

While Britain wanted to keep the colonies and their resources for itself, maintaining imperial control was becoming too costly for the Crown.

At the same time, there was a growing desire and movement towards independence among Britain's colonies, starting with British India.

Meanwhile, the Cold War between the United States and the communist Soviet Union was simmering. It led to the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962.

Closer to home, the proposal to form the Federation of Malaysia -- comprising Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo (today's Sabah), Sarawak, and Brunei -- led to violence in the form of the Brunei Revolt in December 1962 and Indonesian Konfrontasi (which began in 1963).

Meanwhile in Singapore...

Back home, the post-war years were tumultuous. Unemployment was high.

Concerning Malaya, the intention was to transfer power to local governments in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, in line with the British desire to let go of her colonies.

However, in the late 1950s, the British Commonwealth forces were fighting a guerrilla warfare against the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) in what is known as the Malayan Emergency.

The CPM joined with British forces during World War II to fight a common enemy -- the Japanese.

However, now that the war was over, the CPM turned to another goal: Independence.

Singapore is a highly valuable trading port situated in the middle of one of the busiest maritime route in the world. The British did not want to risk letting it fall into the hands of communists.

In their minds, the only way to avoid that was for Singapore to join the Federation of Malaysia and have her internal security controlled by the anti-communist Malaysian government in Kuala Lumpur.

[related_story]

In the PAP

Ever since its inception, the left-leaning People's Action Party (PAP) was split into two camps: The English-speaking camp led by Lee Kuan Yew, and the Mandarin-speaking camp which galvanised the Chinese masses and the trade unions.

The latter was led by the equally charismatic Mandarin-speaking Lim Chin Siong.

Lee Kuan Yew standing next to Lim Chin Siong in the middle. Via NAS.

Lee Kuan Yew standing next to Lim Chin Siong in the middle. Via NAS.

While both sides were fighting for independence, both were ideologically different.

Tensions worsened over matters regarding the Internal Security Council (elaborated below) and Lee Kuan Yew's refusal to release certain political detainees. The party finally split in July 1961 over the PAP's proposed terms of merger with Malaysia.

The folks that split from PAP set up their own political party called Barisan Socialis (BS)

Terms of merger

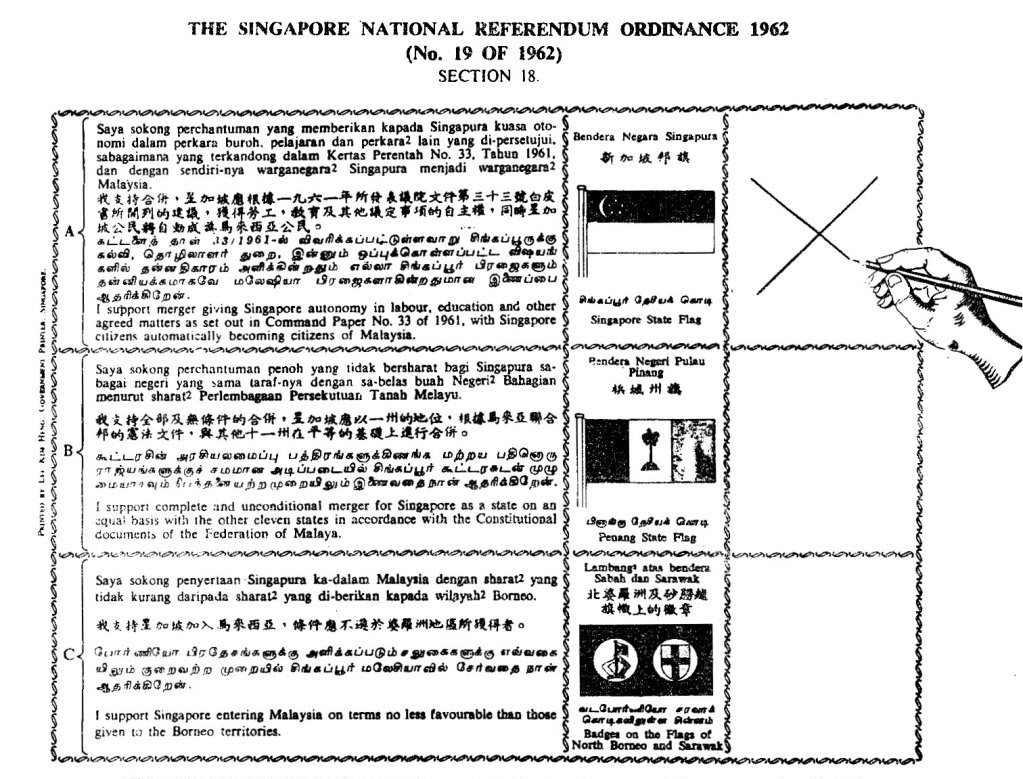

Both PAP and BS were for merger, but wanted to join under different terms and conditions.

Under the terms of merger, the PAP was agreeable to Singapore not being a complete state of Malaysia, but one that is autonomous in all internal aspects except for defence, internal security, and foreign affairs.

Singapore would also not have the full 24 seats in the Malaysian House of Representatives, but only 15 -- the same as the urban centres of Kuala Lumpur and Malacca.

To ease the Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman fears about an overwhelming Chinese population, it was also proposed that Brunei, Sarawak, and North Borneo (today's Sabah) join the Federation of Malaysia.

Without Brunei, Sarawak, and North Borneo, the combined ethnic Chinese population (3.6 million) on the Malay Peninsula would outnumber the ethnic Malay population (3.4 million).

Singapore citizens would also be known as Malaysian citizens, but only be allowed to vote in Singapore elections.

This was done to appease Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman and convince him to proceed with merger.

Merger referendum poster in 1962. The merger terms were put to a referendum, asking the public to vote for which set of merger terms they wanted. An overwhelming portion of Singaporeans supported the first option.

Merger referendum poster in 1962. The merger terms were put to a referendum, asking the public to vote for which set of merger terms they wanted. An overwhelming portion of Singaporeans supported the first option.

To BS, these terms were unacceptable and made Singaporeans second-class citizens. They campaigned furiously to oppose merger on these terms.

One of the Tunku's demands before merger was that the communist situation in Singapore be settled.

The December 8 Brunei Revolt

On Dec. 8, 1962, a revolt occurred in Brunei.

Organised by the North Kalimantan National Army (TKNU), an anti-colonialist liberation army, the rebellion was in response the Federation's plans for merger.

It was later alleged that Lim Chin Siong had a secret rendezvous with the leader of the TKNU, A.M. Azahari five days earlier. What was discussed during the meeting is unclear, but his association with Azahari prompted the Malayan and Singaporean governments to reinforce their beliefs about an imminent violent communist subversion in Singapore.

Further, the Barisan Socialis also publicly announced their support for the rebellion in Brunei.

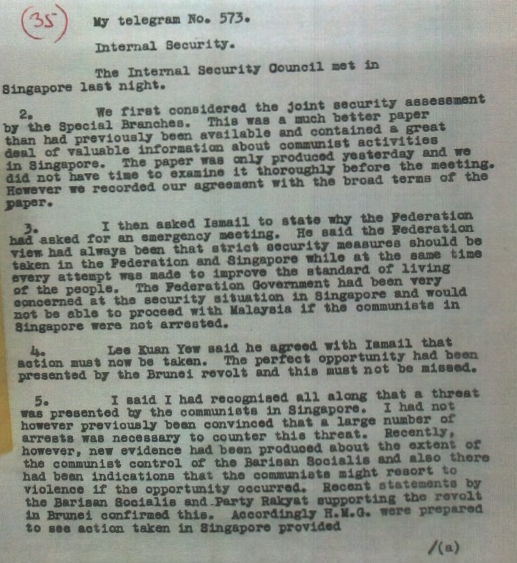

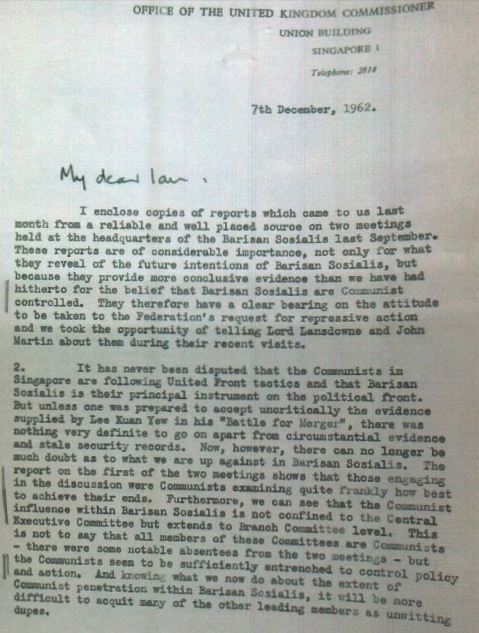

Previously, the Earl of Selkirk, the UK Commissioner to Singapore, was hesitant to approve the arrests. However, the revolt in Brunei and subsequent support by BS prompted him to change his mind.

In a telegram to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Selkirk confirmed that the revolt in Brunei confirmed the "extent of the communist control in Barisan Socialis" and "indications that the communists might resort to violence if the opportunity occured".

Based on these events, the Malayan and Singapore governments sought the approval from the Internal Security Council (ISC) comprising British, Singaporean and Malayan governmental representatives to conduct the arrests.

The governments drafted a list of people to be detained and the British approved it.

In the early hours of Feb. 2, 1963, seven months before merger, Operation Coldstore was carried out by the Special Branch. The arrests were carried out under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance, the predecessor of the Internal Security Act (ISA).

Why people are arguing over Operation Coldstore

Central to Operation Coldstore is the question whether there was a concerted communist conspiracy to subvert the government.

While there is general agreement that there were communist elements in BS, whether it was a concerted effort masterminded by an entity? That's debatable.

The leader of the Communist Party of Malaya, Chin Peng, did mention in his memoirs that the party's underground communist network was indeed smashed after Operation Coldstore.

Some are of the opinion that the whole exercise was an attempt by Lee to quash his political opponents in BS, especially Lim Chin Siong. To that end, they maintain that Lim was unfairly detained and his arrest was not warranted.

In many accounts and speeches, Lim himself defended himself fiercely:

"Let me make it clear once and for all that I am not a Communist or a Communist front-man, or, for that matter, anybody's front-man."

- Lim Chin Siong, July 1961.

He even defended himself up to 1995, a year before he died.

The other concern from Operation Coldstore was the use of the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance (what is now the ISA) to detain suspects, one which the government insists today that protects us from national threats.

The question remains as to how dangerous the communist threat back in the 1960s was given the many different accounts of events put forth by many individuals over the years since.

To better understand Operation Coldstore, you might want to check out the following titles:

- "Original Sin"? Revising the Revisionist Critique of the 1963 Operation Coldstore in Singapore by Kumar Ramakrishna

- Comet in Our Sky : Lim Chin Siong in History by Poh Soo Kai

- Living in a Time of Deception by Poh Soo Kai

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.