"How? The popiah nice or not?" Zita Quek, also known as the popiah matriarch asked. "Is the chilli too spicy? We make it by hand you know."

Packs a punch, humbly

The popiah was indeed something. Soft popiah skin contrasted with a juicy turnip filling -- and the little dab of sambal chilli that packed a punch.

Michael Ker and his aunt, Zita Quek. The family runs Kway Guan Huat Joo Chiat Popiah which produces freshly made popiah skins.

Michael Ker and his aunt, Zita Quek. The family runs Kway Guan Huat Joo Chiat Popiah which produces freshly made popiah skins.

With the recent talk about preserving intangible cultural heritage in Singapore, Mothership.sg decided to pay Kway Guan Huat Joo Chiat Popiah a visit to learn the art of popiah skin-making (and stuff ourselves with their famous popiah).

"My father didn't want me to be in this popiah trade," laughed Michael Ker. "He wanted me to study hard, be educated, and do some other things -- anything other than popiah".

Third generation

The 42-year-old Ker is currently the third-generation owner of Kway Guan Huat.

Ker said: "He knew the hardships of being a hawker so he didn't want me to be in the trade."

Unfortunately for Ker senior, life had other plans for Michael.

After completing a mentorship programme at the Singapore General Hospital in 2004, Ker spent nearly a decade working as a pharmacist, before taking over the family's popiah skin business in 2013.

What is popiah?

Originating from Southern China, the popiah was brought over to Southeast Asia by immigrants from the Fujian province. Popiah is traditionally eaten during the Hanshi (or Cold Food) Festival, from which Qingming Festival -- also known as Tomb-Sweeping -- comes.

During the Hanshi/ Qingming festival, people usually pay their respects to their dead ancestors and eat "cold" foods such as popiah.

Coming to Southeast Asia, the popiah has adapted to local culture and tastes.

In Singapore, the popiah has two variants -- the Hokkien popiah and the Nyonya popiah.

Hokkien popiah tend to have bamboo shoots and pork. The Nyonya type tend to have a seafood-based filling which has prawn or crab meat.

A typical Nyonya popiah consists of sambal chilli, sweet sauce, lettuce, bean sprouts, scrambled eggs, dough batter fritters, roasted peanuts, prawns, and stewed turnips and carrots rolled up in a semi-translucent skin.

"I felt it's quite a pity if I don't carry it on"

Ker's grandfather came over from Fujian in 1938 and set up a popiah skin-making business here.

He married a Peranakan woman from Malacca. Together, they set up a business selling Nyonya-style popiah that catered to the Peranakan community in Joo Chiat.

Kway Guan Huat in the 1980s. Courtesy of Kway Guan Huat.

Kway Guan Huat in the 1980s. Courtesy of Kway Guan Huat.

Today, the 80-year-old business has established a loyal base of customers who frequently patronise Kway Guan Huat to buy handmade popiah skin and condiments to host their own popiah parties.

"Popiah looks like a simple street food, but when you count the ingredients and the preparation [that goes into making it], it's a lot of hard work," says Ker.

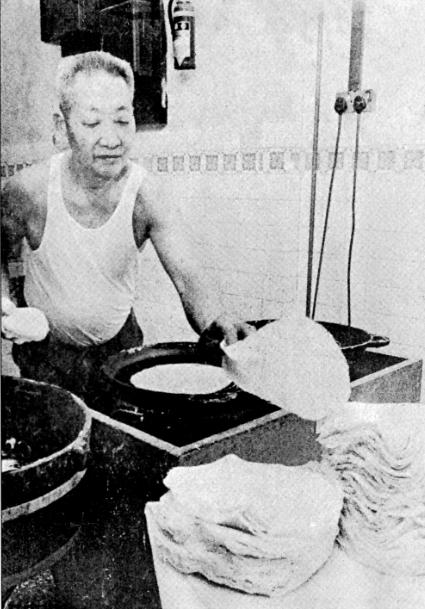

Ker's grandfather making popiah skin. Courtesy of Kway Guan Huat.

Ker's grandfather making popiah skin. Courtesy of Kway Guan Huat.

From mixing the dough to manning the heated cast iron pans (each weighing up to 30kg), popiah-skin making is "sweaty, tough work", according to Ker.

Cast iron pans for making popiah skins.

Cast iron pans for making popiah skins.

During peak festive seasons, the men in Kway Guan Huat can work for 12 hours straight making popiah skin, sometimes starting as early as 2am.

Ker recounted how, in his teenage years, he would come home at 3am and see his father and uncle slogging over all eight iron pans, churning out popiah skins.

"That memory really imprinted on me," he added. "It's something precious and I felt it's quite a pity if I don't carry it on."

Years to master popiah skin-making

It took Ker one whole year to get the hang of making popiah skin, and another few years to fully master the art.

First, the popiah skin dough is created by mixing flour, salt, oil, and water.

According to Ker, the consistency of handmade popiah skin dough is between that of liquid pancake batter and roti prata dough (see video below).

Machine-made popiah skin batter, on the other hand, is liquid, which contains conditioning agents to enable them to last longer.

Ker demonstrating how to wrap a popiah. Handmade popiah skins cannot last longer than a day.

Ker demonstrating how to wrap a popiah. Handmade popiah skins cannot last longer than a day.

In the past, the dough was created by repeatedly beating the mixture with a huge wooden pole. Today, Kway Guan Huat uses an automatic mixer to do that.

After the dough is mixed, it is left to ferment for up to an hour. The fermented dough is then applied to a hot cast iron pan where a thin layer of popiah skin quickly forms.

The effort shows in the handmade popiah skin. Compared to store-bought skin, handmade popiah skin is softer, more translucent, and can only last a day because of the lack of preservatives.

Passing on the art of popiah skin-making

Judging from Ker's dramatic career shift, it's quite evident this man is bent on preserving the art of popiah-/ popiah skin-making.

Over the years, he has been providing live demonstrations on popiah-making to various youngsters such as secondary school students and girl guides.

Customers patronise Kway Guan Huat to get all the condiments (such as sweet sauce) and ingredients they need for a popiah party.

Customers patronise Kway Guan Huat to get all the condiments (such as sweet sauce) and ingredients they need for a popiah party.

His shop along Joo Chiat Road is also currently undergoing renovations to include a heritage gallery that showcases popiah-making equipment and hands-on demonstration for visitors, where they can learn more about its history.

These will be ready by 2019.

Popiah and Kueh Pie Tee from Kway Guan Huat.

Popiah and Kueh Pie Tee from Kway Guan Huat.

[related_story]

"I want to do all this to let the younger generation know about it," said Ker. "Once it is lost, it can never be brought back. There must be continuity."

Unfortunately for Ker, he and his wife does not have any children that he can pass on this craft to anytime soon.

"I hope that somebody continues it and make it 100 years of history," he adds.

"If that somebody is going to be doing this, I have the obligation to make sure the person is doing this for the right reason. I think it's very important where the heart is."

"If you don't have the heart or passion, I don't think you can master it well."

All images by Ilene Fong, unless otherwise stated

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.