During transport operator SMRT's annual review on Wednesday, Mar. 28, CEO Desmond Kuek announced that rail reliability last year has improved based on the Mean Kilometres Between Failure (MKBF) indicator.

We bet this is what you look like after reading the above sentence:

And we understand why, since there were a couple of big incidents amongst several other train faults that happened last year.

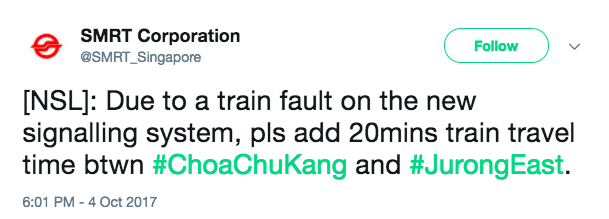

Here's a selection:

We could go on, but we've made our point.

But all that said, numbers don't lie, so here's what we understand about how they arrived at this splendid conclusion:

What is Mean Kilometres Between Failure (MKBF)?

MKBF is an international performance indicator for rail reliability.

It simply measures how far trains travel before experiencing a delay that lasts for more than five minutes.

The bigger the number, the lesser delays are experienced, the happier commuters get.

Simple enough? Great.

[related_story]

And what is SMRT's current MKBF?

The MKBF for the train lines SMRT runs has (somehow) roughly doubled throughout the three train lines for the whole year of 2017, in comparison to 2016.

In Dec. 2016, the MKBF for North-South Line stands at 156,000km and jumped to 336,000km in Dec 2017.

The MKBF also increased on the East-West Line, from 145,000km to 278,000km, while the Circle Line improved from 228,000km to 523,000km.

This means SMRT faced fewer delays in 2017 than it did in 2016.

Now, here's where we should add some comparative context so you can understand this better, though:

- In 2017, Transport Minister Khaw Boon Wan noted that the Taipei Metro clocked 800,000 MKBF in 2016.

- Hong Kong's MTR clocked 520,000 MKBF in the first quarter of 2016, but that figure goes up to 900,000 if you factor in their longer-distance regional lines.

How could it possibly have gone up??

We know, it sounds pretty impossible for it to be twice as reliable as in 2016, given the delays, disruptions and even that calamitous collision Singaporean plebeian commuters faced in 2017.

Like these cases, for example:

Here's the reason:

Not counting the disruptions & delays caused by kinks in the new signalling system

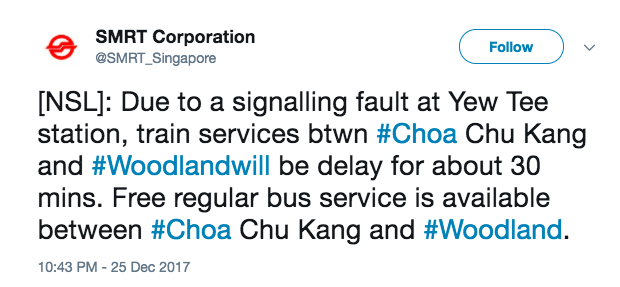

You see, a good number of these MRT disruptions happened as a result of the new communications-based train control (CBTC) signalling system, as you can see in the chart below:

via SMRT

via SMRT

These signalling faults — the incidents charted by the red bars — should by right have very much affected the MKBF indicator, but none of them did, simply because they weren't included in the MKBF numbers.

Kuek explains:

"MKBF data is used for comparing the intrinsic reliability of the network from year to year, without the temporal and possibly distortive effect of short-term projects.”

And how can SMRT conveniently discount the signalling-caused faults?

Seems it wasn't an "ownself-discount-ownself" type situation — SMRT's CEO for trains, Lee Ling Wee, said the decision to do so was made by both SMRT and the government collectively.

Can they subsequently artificially elevate the MBKF through the injection of more trains? Lee says no — because, he says, if the system remains fault-ridden, no number of trains will be able to up the reliability rate.

Now, since we're on the topic of delays, let's talk about something else everyone has inevitably complained about before:

SMRT's completely off-the-mark claims of "additional travelling time" during delays

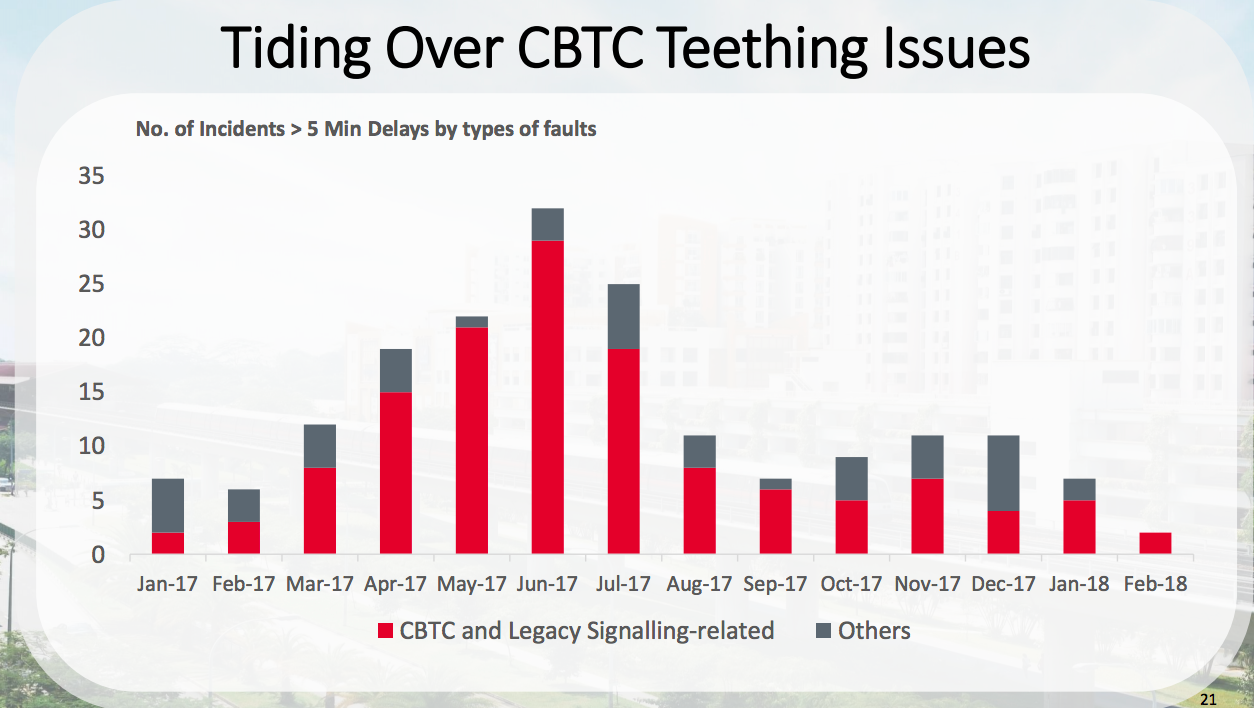

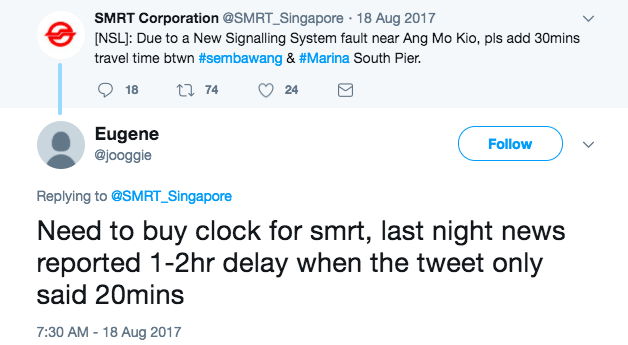

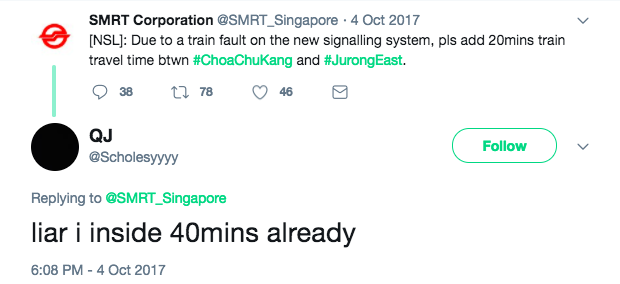

Yes, those fascinating tweets and Facebook posts from SMRT's official social media that convey their estimates of how travel times are affected whenever there is a delay in train service due to reasons ranging from faults to platform screen door closing issues.

For some reason none of us could ever understand, the times reported by SMRT pretty much never coincided with commuters' actual experience of them.

Here are just two examples:

And what's the reason for this?

Estimations based on engineers' technical assessment of the time needed to fix the problem

That's because previously, the tweets and Facebook post time estimates were based straight off the technical assessment of SMRT's engineers, who look at how long a faulty train in question has stopped, as well as the time needed to rectify whatever problem caused the delay.

Unfortunately, these engineers' estimates don't tend to factor in the actual on-ground time delay experienced by a commuter —when there is a fault, it's obvious that all trains moving on the line are hit by it, because they get bunched up from one train after another being delayed by the first faulty one.

So even after a fault is sorted out, more time is taken in a) clearing the first train from the line, if needed, b) getting the rest of the trains moving and c) clearing the crowd of passengers that accumulate at every station, who cannot board the stalled trains that are already packed and delayed.

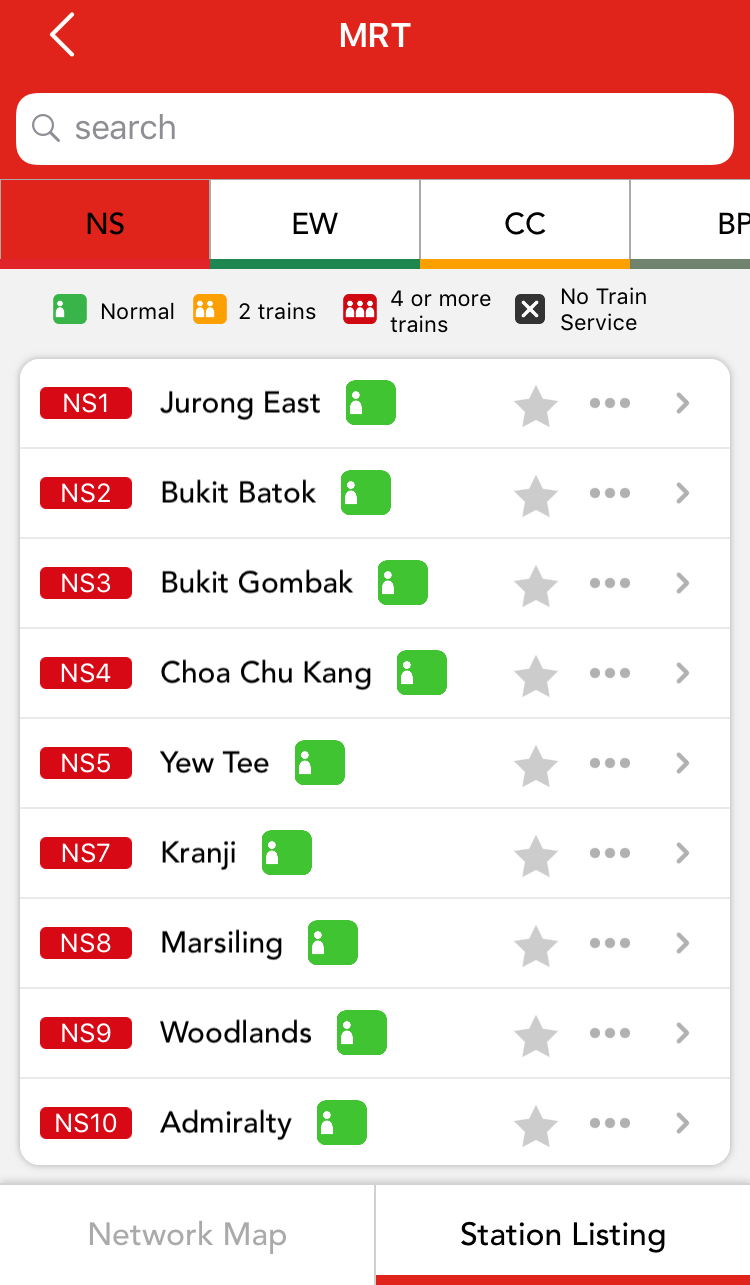

Kuek, who explained this in remarks he shared with the media on the company's progress on this front, says these real-time, on-ground factors will be factored into SMRT's latest version of its mobile app "SMRTConnect".

One of its interfaces shows you if you'll be able to board the train as soon as it arrives, or if you'll have to wait for two trains to pass you by, or four, or more, or if there's a complete disruption:

Screenshot from app

Screenshot from app

... that said, they haven't told us if this means we should completely disregard their tweet time estimations. So...

What now?

SMRT says it has a goal of reaching 1 million MKBF by 2020. This means having less than an average of one incident delay (of five minutes, bear in mind) per month on the North-South line.

From where we're standing, that is one big ambition. And Kuek agrees.

But if your trust in the MKBF indicator is starting to wane (because they could just discount this or that upgrade or blame it on this or that system change, right?), know that SMRT has also ambitiously said it's working toward zero safety accidents, as well as zero delays of more than 30 minutes, caused by anything at all, by 2020.

We'll see.

Top image via SMRT

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.