From 2018 to 2022, public transport fare adjustments will be determined by a new formula that will kick in from the end of this year.

This new formula takes into account the rising, as well as the changing nature, of operational costs, decreased public transport productivity, and includes a new component called the Network Capacity Factor (NCF), which Minister for Transport Khaw Boon Wan says is a "sensible" introduction:

And we knew this was coming. This formula change was previously announced by Khaw in Parliament earlier this month:

Nonetheless, it is still important we understand the what, the how, the when, and the why. So here goes:

Why is there an adjustment in the formula?

For starters, the current formula that kicked in at the end of 2013 will expire at the end of this year. The fare formula has to be rejigged every five years.

That aside, the adjustment is also needed to account for an increasing gap between operational costs and fare revenue.

Over the past five years ending last year, Singapore's public transport capacity increased by 25 per cent thanks to a big injection of buses and trains.

Under the Bus Service Enhancement Programme, the government added 1,000 new buses. The third section of the Downtown Line also opened in October 2017, and around 200 new trains were injected into the rail network.

With this in mind, while operating costs increased by over S$900 million between 2012 and 2016, annual fare revenues increased by only S$230 million -- and the bulk of the fare revenue increase wasn't even due to fare increase. Rather, it was due to increased ridership.

[related_story]

These heightened costs didn't exist five years ago, and so it's fair — arguably necessary — for the revised formula to reflect these changes.

So what's the current fare formula?

To recap, here is the formula that is currently being used to determine your public transport fares:

It currently comprises two parts:

- The Price Index (made up of Core Consumer Price Index, the Wage Index, and the Energy Index) i.e. staff wages, fuel costs and maintenance of assets, and

- the Productivity Extraction, which is basically the discount commuters get when transport operators are super productive. It's in red because it is a deduction from the overall fare calculated — the higher that number is, the better it is for us — the higher the discount on the eventual fare calculated.

And what will the new formula be?

It will come with three changes:

- An increase in weightage of the Price Index (i.e. operating costs will be factored in more into the calculation), from 40 per cent to 50 per cent of the formula

- Lowering of the Productivity Extraction (i.e. lower discount, from 0.5 per cent to 0.1 per cent. i.e. sad.) and

- Inclusion of a new component called the Network Capacity Factor. Don't worry, we'll explain what this is in a jiffy.

Why decide on these 3 changes?

1. Rise in weight of Price Index

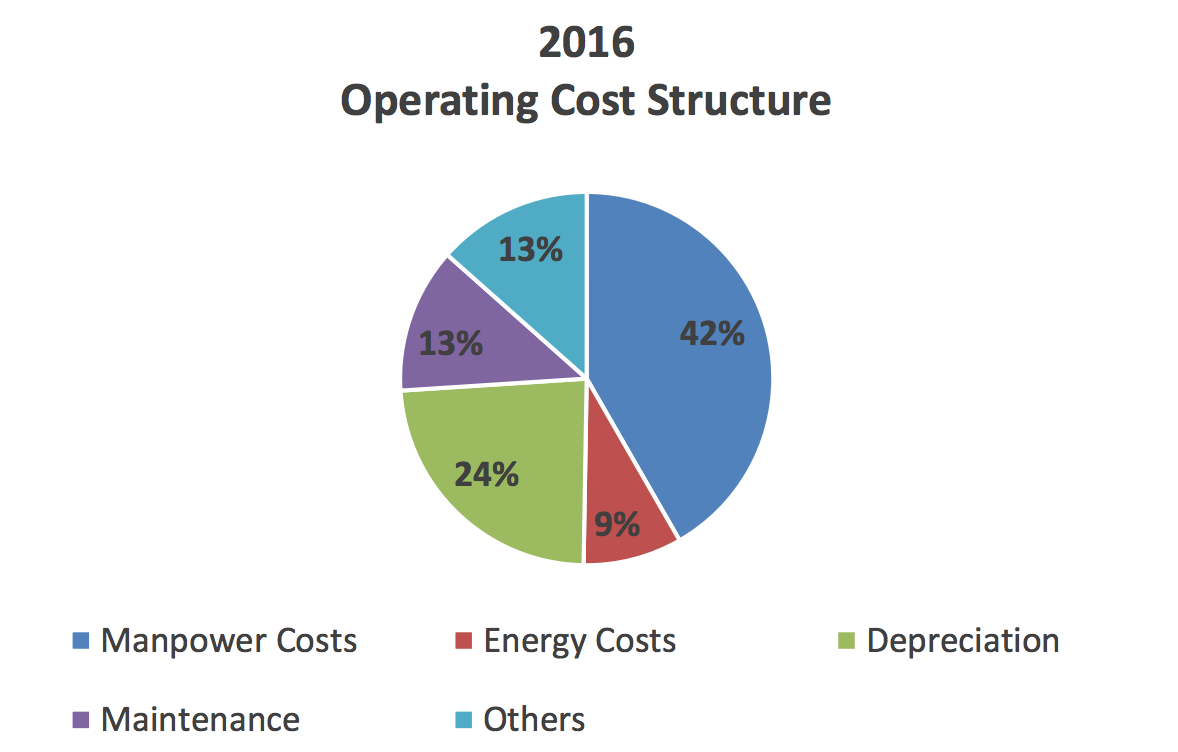

The Price Indices reflect what make up the operating costs for the public transport industry.

For example, the old formula reflected that in 2012, 40 per cent of operating costs was for maintenance and operation, 40 per cent of operating costs went to paying for wages of public transport workers, while 20 per cent of operating costs went to paying for energy.

These proportions changed in the last 5 years.

Now, about 10 per cent of operating costs go towards paying for energy costs while nearly 50 per cent now come from operations, maintenance, and asset depreciation (like the value of buses and trains as they age).

Courtesy of PTC.

Courtesy of PTC.

And that's why this in particular has to be changed, to accurately reflect the cost of running public transportation.

2. Lowering of Productivity Extraction

The Productivity Extraction, as we explained earlier, takes productivity gains and and shares it with commuters in the form of a "discount". In other words, the more productive the public transport operators are, the bigger the number, and therefore this reduction in the fare formula.

In determining the old fare formula, the estimated productivity gain of the public transport operators in 2012 was 1 per cent. Half of that gain (0.5 per cent) went into the Productivity Extraction.

From 2012 to 2016, however, the public transport industry only managed a paltry productivity gain of 0.2 per cent -- which means half of that (an even sadder 0.1 per cent) will be used for the productivity extraction component.

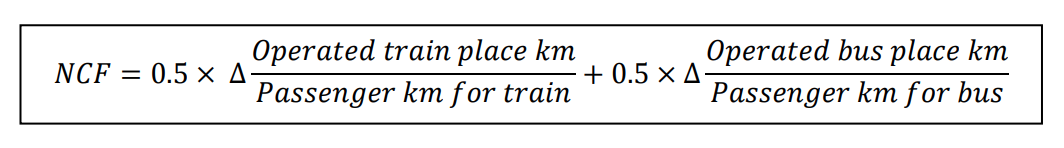

3. Inclusion of Network Capacity Factor (NCF)

Now, if you've been reading carefully, you might have noticed that the old formula did not cover the costs incurred from increasing our public transport capacity.

This kind of cost comes from differences in supply and demand. For example, running an empty bus costs money that no one is paying for (because not many passengers are riding those buses).

This new component to be added into the formula capacity calculates the costs that come from building more lines or injecting more buses or trains into the public transport system that are in excess of passenger demand.

This is derived from the formula below:

Courtesy of PTC.

Courtesy of PTC.

So this formula takes the "supply" of trains and buses that are running on the roads and tracks, and divides that by the "demand" (or distance travelled by each passenger) of public transport commuters on the network.

If supply outstrips demand, the NCF will be positive, resulting in an increase in fares.

Conversely, if demand were to outstrip supply, then the NCF will be negative, and will trigger a decrease in fare.

Lastly, if demand were to equal supply, then the NCF would be zero; it won't make a difference to the fare adjustment process.

Therefore, it is in your best interest for everyone to take more buses and trains — if just to impact this component.

In order to prevent supply from outstripping demand too quickly (such as opening a new rail line), the Public Transport Council (PTC) will exclude new rail lines for the first 18 months of operation, in order to allow ridership to build up and stabilise.

So will there be a fare increase come end-2018?

No one knows (at least officially) for sure now if it will go up or down just yet, and we'll tell you why.

For one thing, the 2018 fare review exercise, which is done every year, will be finalised in the third quarter of this year. It will incorporate this new fare formula, and we will only concretely know then.

However, it certainly is worth keeping in mind the fact that fuel prices, which impact the energy index component, are the most affected by fluctuations — both upward and downward, to be fair — and so even if fuel prices drop, the component, which is now smaller, will have a smaller impact on the eventual fare change.

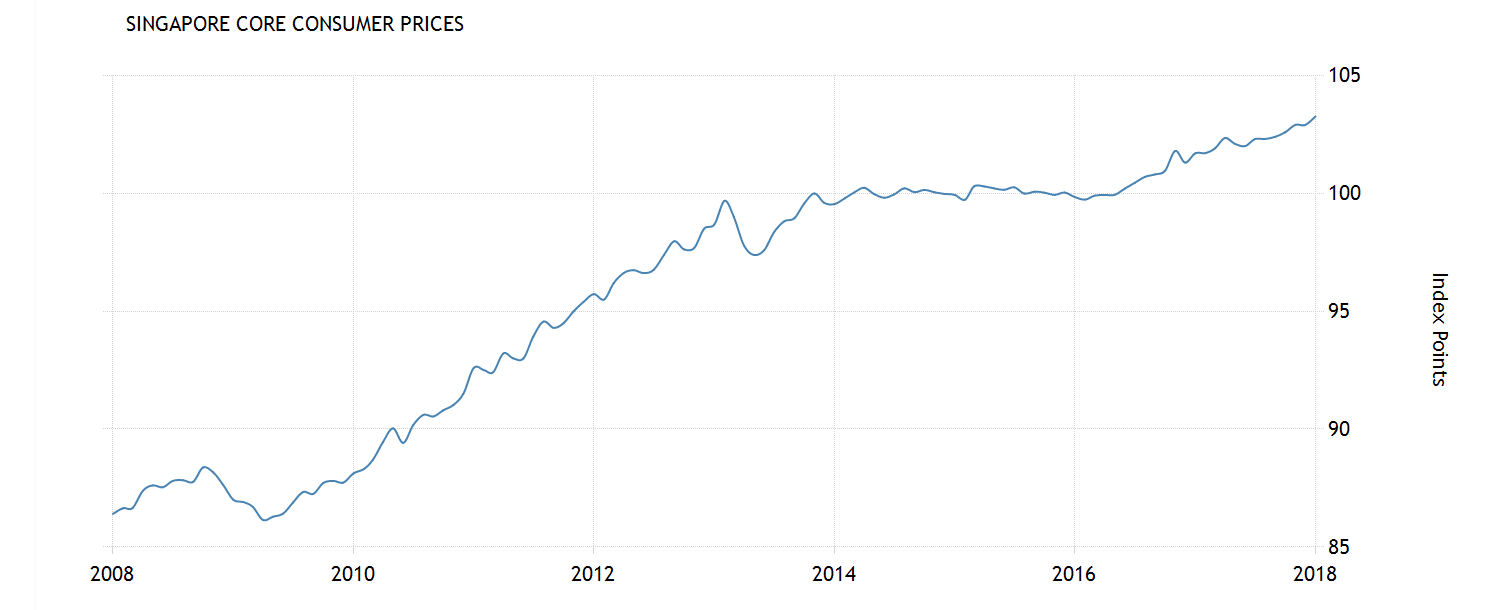

On the other hand, we can pretty much be assured that the price index will almost always go only one way. Here's the overall core consumer price index over the past decade:

Core Consumer Price Index from 2008 to 2018 in Singapore, via here

Core Consumer Price Index from 2008 to 2018 in Singapore, via here

But there is one thing we do know: during last year's fare review, the PTC had a quantum of 5.4 per cent to play with to reduce fares.

At that time, however, they only used 2.2 per cent of it for the reduction in morning pre-peak travel fares. That leaves 3.2 per cent that the PTC can still play with to weave into fare calculations at any point in time.

And so in honesty, it's hard to say, because it really depends how much of this reduction they're going to weave in this year, if at all.

But what about low-income commuters? Won't this hit them hardest?

Interestingly, public transport fares have become increasingly affordable as a whole for the average user — especially for lower-income commuters.

As Minister Khaw mentioned in his Committee of Supply speech, the PTC tracks the affordability of public transport fare regularly.

They found through surveys with commuters that for both average and lower-income public transport users, monthly public transport expenditure as a percentage of household income has been decreasing for the last decade.

In other words, according to the PTC, the majority of public transport users are spending less of their income on public transport, meaning it has become increasingly affordable, despite the overall fare increases over the years.

In 2007, the percentage of people's incomes spent on public transport was between 3 per cent and 4.2 per cent. In 2017, public transport expenditure dropped to between 1.9 per cent and 2.7 per cent of household income.

For lower-income commuters who still struggle with fares, the government will also continue to provide an estimated S$9 billion over the next five years as subsidies for public transport services.

Top image by Joshua Lee.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.