It's the outcome the general public was all waiting for, but was perhaps hoping not to get.

The Court of Appeal, Singapore's highest court in the land, convened a five-judge panel comprising three High Court judges and two judges of appeal just to hear and deliberate the City Harvest Church (CHC) leaders' funds misappropriation case.

Their decision?

To uphold the sentence made by the three-judge High Court panel in April 2017, which was to slash their sentences by about half -- for some, more, and for others, slightly less:

Here's a quick rundown of that:

1. Who were these judges who decided this?

(from left to right): Judge of Appeal Chao Hick Tin, Justice Woo Bih Li, Justice Chan Seng Onn. Justice Chan felt their longer sentences should stick, while Judge of Appeal Chao and Justice Woo decided to shorten them. (Pics via Supreme Court website)

(from left to right): Judge of Appeal Chao Hick Tin, Justice Woo Bih Li, Justice Chan Seng Onn. Justice Chan felt their longer sentences should stick, while Judge of Appeal Chao and Justice Woo decided to shorten them. (Pics via Supreme Court website)

In the first round of appeals in the case at the High Court, a three-judge panel came together to form their eventual 2-1 decision of shortening the sentences of the convicted.

Now, different to this is the Court of Appeal, on which sit special judges called Judges of Appeal.

One of them, Judge of Appeal Chao Tick Hin, joined High Court Justices Woo Bih Li and Chan Seng Onn (they're pictured above) in considering the appeal at the High Court level.

These three judges, therefore, were not part of the group of five who deliberated the state prosecutor's final appeal at the Court of Appeal level.

The five, and they unanimously agreed with the High Court's majority thinking. (Photos via Supreme Court website)

The five, and they unanimously agreed with the High Court's majority thinking. (Photos via Supreme Court website)

Thus, we had two other Judges of Appeal Andrew Phang and Judith Prakash, joined by High Court Justices Quentin Loh, Chua Lee Ming and Belinda Ang.

[related_story]

2. And why did they decide to go that way?

Interestingly, all five agreed that the CHC leaders' criminal breach of trust, by the letter of the law, did not meet the requirements for the more grievous type of criminal breach of trust (Section 409, which comes with up to life imprisonment).

Section 409 defines those who should fall into that category as "a public servant, or in the way of his business as a banker, a merchant, a factor, a broker, an attorney or an agent".

The summary of their answer to the public interest question of who is an agent? Not the CHC folks. Or directors or board members, or their trustees or majority shareholders of a company, much less of a charitable organisation -- which CHC is considered to be.

Therefore, these are the estimated dates they'll all be released from jail:

So was it because the CHC folks had superb lawyers? Or did the prosecutors do a poor job?

The answer to both questions is no. They are the wrong questions posed.

Nor was it because these folks, or this church, happen/s to be wealthy.

Actually, Kong Hee and friends got shorter sentences for the sole reason that they got lucky -- on a flawed and outdated law.

This is none other than Section 409 of the Penal Code, which defines the most severe form of criminal breach of trust so narrowly that the Singapore judiciary realised it doesn't happen to include the folks at the helm of organisations, who control millions of dollars -- like in this case.

So why couldn't the Court of Appeal do anything about that?

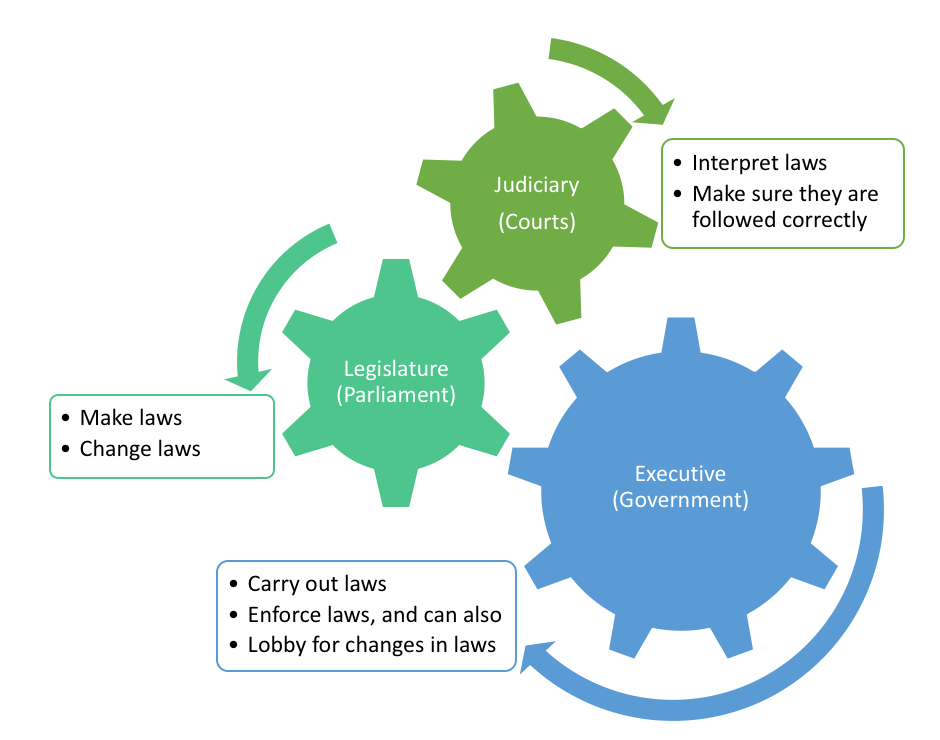

The answer to that lies with how Singapore's power is separated:

Nifty cog wheel diagram done in PowerPoint by Jeanette Tan

Nifty cog wheel diagram done in PowerPoint by Jeanette Tan

The constitution of Singapore uses Government to refer to the Executive branch, made up of the President and the Cabinet.

Turning back to the case at hand, the fact is, our court judges cannot say,

"The law says A, but we are going to read it as B instead so that these guys can be thrown in jail for longer because we think they deserve it."

Instead, as is what happened here, our Court of Appeal has more or less said,

"The law says A, but these guys are B. We can't assume that it also includes B. A is very narrowly defined in this law, and as it stands, this law also doesn't make sense in today's context. It's also really old and probably has been outdated for hundreds of years, but sorry, we don't have the right authority to do anything about that. It is still the law. And it still says A."

So what to do, then?

Change the law, of course, but that will have to be done by Parliament, the legislators.

(In case you're interested, here is what was actually said by the Court of Appeal:

"But the Court of Appeal was of the view that the task of law reform should be left to Parliament. The courts were ill-suited, and lacked the institutional legitimacy, to undertake the kind of wide-ranging policy review of the various classes of persons who, having regard to modern conditions, deserve more or less punishment for committing CBT. It observed that such a review was not only essential but also long overdue owing to the dated nature of the provision." [emphasis ours])

Here's some good news, though:

The government (the executive, who are in a pretty good position to lobby for laws to be changed in Parliament — the legislature, remember?) appears to be on the public's side on this one.

In a statement responding to the news of the final verdict, the Attorney-General's Chambers (state prosecutors) said:

"Given the Court of Appeal’s decision, the Attorney-General’s Chambers will work with the relevant ministries on the appropriate revisions to the Penal Code, to ensure that company directors and other persons in similar positions of trust and responsibility are subject to appropriate punishments if they commit criminal breach of trust." (emphasis again ours)

In other words, they're gonna try to update the laws to terms that make more sense and which do cover cases like this.

Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam also put up the following short, but pretty severe-sounding post on Thursday afternoon, the same day the CHC case concluded:

"The Court of Appeal has ruled on the CHC matter. Attorney-General's Chambers has issued a statement.

This is a serious matter.

I will make a Ministerial Statement in Parliament on the Government's position."

In conclusion:

1. Laws are made by politicians. Politicians are elected by you, the people. Your vote matters.

2. Laws can be made, and can also be changed or updated. They're not the perfect be-all and end-all, forever. Because things change. Societies change. We change.

3. Judges only read the law and make sure it is accurately interpreted. They cannot make or change laws, even if they think it's screwed up. That work is for politicians/ parliamentarians (refer to points 1 and 2).

The end.

Related stories:

Top photo via City News

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.