No one likes higher taxes or a higher goods and services tax (GST) — even if it is only coming in a few years' time.

So of course, some Singaporeans have come up with different creative excuses reasons to “persuade” the government not to increase GST.

Source: Today Facebook.

Source: Today Facebook.

Source: Today Facebook.

Source: Today Facebook.

When public intellectual and economist Donald Low posted on his FB that he was of the view that if we use more of the government’s Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC) and GST may not need to increase, many Singaporeans latched on his intellectual argument and agreed too:

To know more about the NIRC, see our nifty chart and simplistic Chinese New Year analogy explanation near the bottom of this article.

Indranee Rajah: "Preserving our Inheritance"

Enter Senior Minister of State for Finance and Law Indranee Rajah.

In a FB post that was shared at almost midnight yesterday, Indranee argued against the Singapore government using more of the NIR from our reserves:

The more-than-50 per cent of NIR argument

First, Indranee argued that a suggestion of using, say Low's suggested 60 per cent of the NIR, is making four assumptions.

Assumption 1: That an additional 10 per cent of NIR (from 50 per cent to 60 per cent) will always give the government the same amount as a permanent 2 per cent GST increase.

Assumption 2: That the amount of returns generated by the reserves will always be the same. But there will be volatility in investment returns and it is difficult to eliminate investment risk.

Assumption 3: That Singapore will never have to draw on the principal amount of reserves on which the returns are generated. The government, she reminds us, did so in 2009, during the global financial crisis.

Assumption 4: That the government can get the same returns on a principal amount that is growing at a slower rate. It is not a wise assumption because if we use more (60 per cent instead of 50 per cent), we save less. This means that less is reinvested and we will have less to spend over the long term.

The argument for 50 per cent + 2 per cent extra GST

Indranee said the government used 50 per cent as a gauge to be "fair and prudent". In other words, the government spends half now, and saves half for the future.

And since the NIRC is the biggest source of money for the country's expenditure at the moment, she argued that the government would be over-relying on the yield from our reserves if we decided to take more from the NIR.

She also reiterated that the government will keep making sure the less well-off are buffered, with the low- and middle-income receiving more support — hence her conclusion that there is the need for an increased GST as a "continuing and sustainable source of revenue to fund our future needs", which include healthcare, infrastructure, security and education.

[related_story]

Low did acknowledge this in a follow-up Facebook post on Tuesday night, noting that the reserves will grow at a slower rate. At the end of the day, Low wrote, it depends on how much we value our present as compared with our future, and is eventually an "agree to disagree" scenario:

"My reason for supporting a higher spending limit and hence a slower rate of reserve accumulation is that future generations are likely to be richer than the current generation entering retirement. But you’re of course free to disagree with my optimism."

"GST hike not the only option considered for raising revenue"

Separately, Indranee also shared on 938NOW that GST hike was not the only option that the government explored.

However, she said again, "GST is the one that will give you, over the long term, a sustained revenue of sufficient amount that will take care of our expenditure needs".

Earlier on Tuesday, she also told the media that spending a higher percentage of the returns could be going down a "slippery slope" and that the authorities would have to make the principal sum of reserves "work a lot harder".

This may mean taking on more investment risks.

However, it's nice to know that Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat isn't closing the door fully on the discussion on how much we take from our investment returns.

In his interview with The Straits Times a day after the Budget, Heng said the numbers (from NIR) might be debated, but what is more crucial is the principle that every generation pays its fair share.

We can all agree with that.

The Net Investment Returns Contribution — an analogy in oranges

Let's say you've got a basket of oranges. Like this one:

Photo via Pixabay

Photo via Pixabay

You know that your kids will need some oranges to eat in future, but you also need oranges to eat now.

So, in essence, you need more oranges.

You take two of the oranges from the basket to go visit your relatives and wish them well in the new year:

Source: Getty Images

Source: Getty Images

And in return, you get your oranges back, and also... ang baos:

Yeyyy. Source: Getty Images

Yeyyy. Source: Getty Images

So what do you do with these oranges and ang bao money? You put the oranges back into your basket:

Photo via Pixabay

Photo via Pixabay

And then you take your ang bao money and spend it on something fun like Ban Luck (blackjack) or mahjong. And then, hopefully, from there, you make more money from winning.

And then you use some of that money to buy more oranges to put in your basket...

Adapted from Pixabay picture

Adapted from Pixabay picture

... while taking another portion to continue playing games to win more money to buy more oranges. And with the new year, you bring the newly-purchased oranges out again to do your rounds of visiting, and continue to put more oranges into the basket.

This, in essence, is the simplest form of how our reserves and investment work.

Prior to 2009, the government grew its basket of oranges by:

a) "investing" groups of oranges by doing lots of visiting, and then taking in lots of angpow money, and

b) giving away pairs of oranges to the idiots who forget to bring them for visiting, and then getting them back together with, say, an extra because the orange-borrowers 'owed them one' (i.e. two oranges became three).

It could then take half of the angpow money and extra oranges it gained to spend on the country and whatever it needed, while the rest of the gains went back into the orange basket so that it continues to grow. This is also known as...

net investment income (NII).

For the financial year of 2009 onwards, though, the government decided it could figure out a way to safely use more angpow money (not the oranges, mind you) for spending. They did this through the...

net investment returns (NIR) framework.

This is a bit more difficult to explain using oranges, but the idea is this:

You have that basket of oranges, right? And you've taken some of the oranges to "invest" so you can receive more oranges and angpow money in return. And after playing enough mahjong and blackjack you've realised you can predict how much you'll make from your gambling. And then you decide you can take half of the predicted amount (you know, just in case you eventually end up earning a bit less than that amount) to spend.

Except this time, the amounts involved are in the billions. And they're handled by three investment companies: Temasek, GIC and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS).

What if they lose money on their investments, like big-time?

Good question. The government investment bodies quite likely invest in really rock-solid stable things, though — (think about how there are types of investments that come with guaranteed interest rate returns, for instance) only some of these investments are as risky as blackjack. Most of these are probably grounded in very clear and certain things that can definitely make Singapore money. Our guess is our government investors are a very conservative group of people, not to worry.

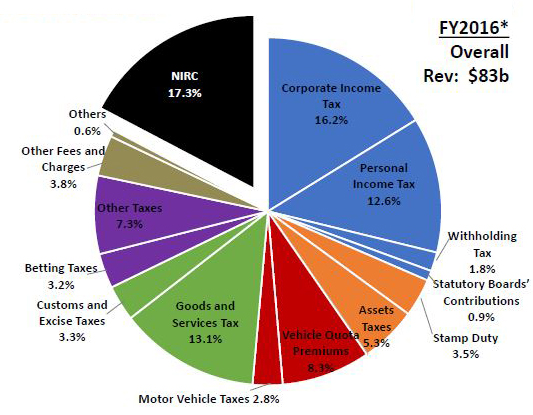

So that's the NIRC, in a nutshell — or in this case, an orange basket. It's made up of half the NII and half the NIR, to form the amount of money the government allows itself to spend every year in the Budget.

This is important because now, the Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC) has overtaken corporate tax to become the largest single contributor to the government’s coffers.

The NIRC will more than double from S$7 billion in FY2009, to an estimated S$15.9 billion for the financial year ending March 31, 2019.

GST and personal income tax are expected to constitute S$11.4 billion each towards the government's operating revenue for FY2018, while corporate income tax is set to contribute S$15.1 billion.

Top photo from gov.sg YouTube.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.