In 2013, a girl met an incredible taxi driver who overcame his lack of formal education and ability to read, and had read books on English law, the Cold War, classic greats in literature, engineering, Winston Churchill and the Economist.

She wrote about her encounter with him on Facebook, and the post went viral — once that year, and a second time two years later when it resurfaced.

Four years later, she was on a panel at a big-time conference discussing whether or not Singapore can sustain itself as a “vibrant, cosmopolitan global city”.

There, she made a badass speech about the arts in Singapore that drew an unexpectedly emotional response from Ambassador-at-large Tommy Koh.

But neither of these stories, true as they are, are what 28-year-old Amanda Chong would want to be known for.

Achieved aplenty

What does she want to be known for, then? Does she even do the things she does or has done, to be known?

It’s clear she doesn’t need to, really.

She went to both Harvard and Cambridge to read law, and could in all likelihood have gotten a Big 4 firm job with far better monetary prospects than what she ended up doing — prosecuting sex crimes for the state, certainly not as well-paying as a high profile private sector litigator or corporate lawyer.

Her flair for poetry has achieved the following - having one of her poems engraved on the Marina Bay Helix Bridge; some poems being used in the Cambridge International GCSE syllabus, as well as in her very own book compilation.

Professions (2016), by Amanda Chong. You can get it here.

Professions (2016), by Amanda Chong. You can get it here.

Overcoming the education gap

So we sat down with her after sunset, in a bid to understand her psyche, and one of the first things she speaks about reflects a remarkable self-awareness:

“I recognise that I am incredibly privileged. I have had so many chances to study overseas and I feel it’s a moral responsibility to use my personal resources in order to lift up other people… If I believe in equality, what am I doing to advance equality?”

The answer to that rhetorical question is, in her case, more than quite a few of us actually.

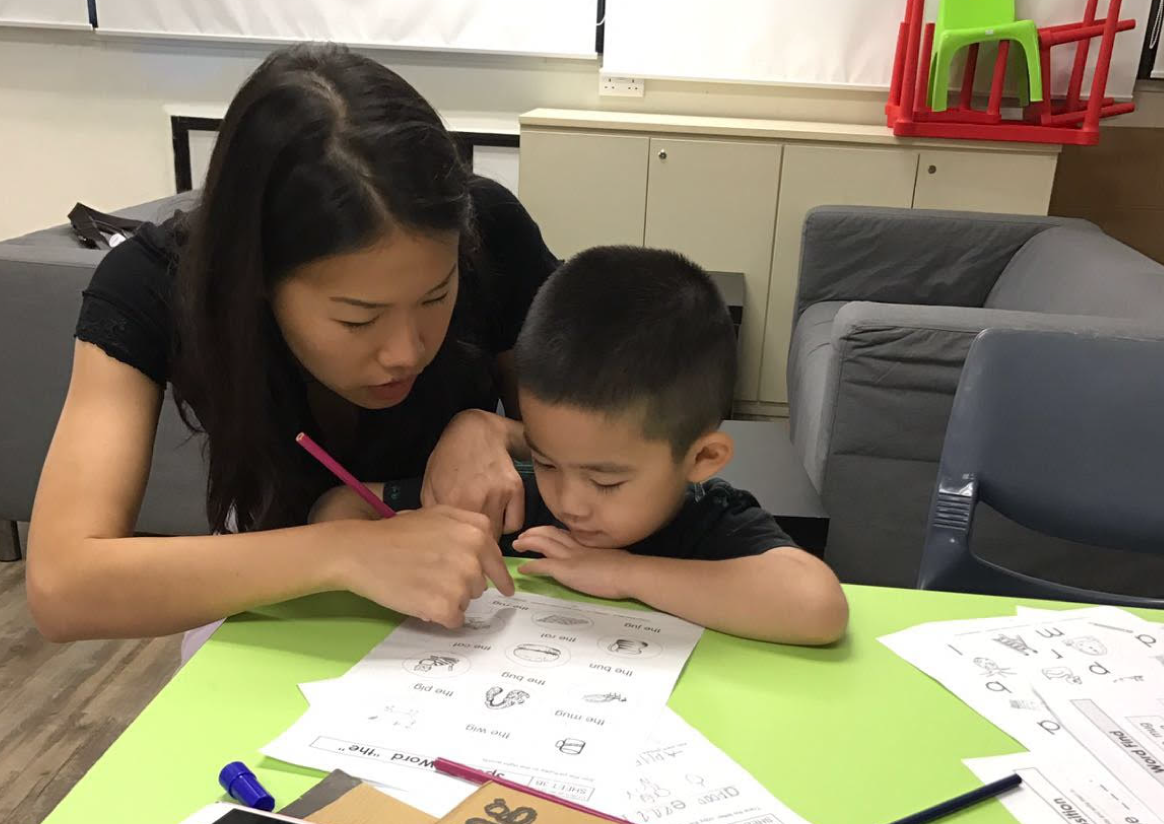

Chong, together with two noble colleagues at the Attorney-General’s Chambers, started a project reading to underprivileged children, at the same time teaching them to read.

Called ReadAble, it started in 2014 at a migrant mom’s one-room flat in Jalan Kukoh, which they used as a classroom, and as the number of volunteers helping out grew, they bought books and started a mini-library there as well.

Why reading, we asked? A voracious reader since she was a child, Chong said she was raised to believe that reading is intimately linked to life opportunities.

“My father grew up in a very underprivileged background. He used to live in a one room flat with his seven siblings. What made a huge difference for him was reading – he became the first person in his family to go to university because of that.”

Because of these circumstances, she also realised that there were many children who, because of their inability to read, often got left behind in primary school:

“Primary schools presume that you know how to read… but some parents experience such huge challenges. They just don’t have the same level of resources to give to their children. These kids are left behind.”

Choice to be a lawyer & poet also stemmed from desire to serve

Her strong values also informed her decision to become a deputy public prosecutor — to her, it was one of the more straightforward ways she thought she could put her idealistic values into practice and help serve the public interest:

“I believe that law is the language in which society’s ideals are enacted. I wanted to do something in the public interest… I had no interest whatsoever in being a corporate lawyer.”

In her poetry, Chong also strives to highlight the perspectives of women by placing them in public consciousness.

She explained excitedly that her efforts in writing are to “redress” a “huge historical debt” from women being excluded from centuries of literature, chiefly because they were not allowed to write books.

To do this, Chong imagines herself in the shoes of other women who suffered as victims of gender violence.

She reads court cases and judgements to get clues on these women’s perspectives, and in her poetry attempts to reflect the voices these women did not have.

“For those who did not get a chance to speak before, and in some ways, cannot speak — how can I help to reflect that?”

One of her poems, for instance, is about the famous 1965 Sunny Ang murder case — Ang, a one-time Grand Prix driver, killed his girlfriend in order to benefit from her insurance money.

She also says her book of poems, Professions, “explores the gender power dynamic of how women were excluded from professional life.”

But why care so much about women?

Chong’s passion for women’s rights and interests also stems from her own experience while in school at Harvard.

She recounts how in class, the boys did most of the talking and seemed to have much more confidence than the girls.

“A lot of women struggled with this, and they were not graded as well even though they were incredibly brilliant. Women would also apologise before asking a question.

Why do women have such a crisis of confidence?”

She notes as well that women are inevitably more greatly affected by gender-linked and sexual violence than men:

“[Gender violence] changes your experience of life and a public space. It affects the way you interact with the world and causes you to lose confidence or not feel so comfortable in certain spaces. So I think it is important to address that.”

Doing (even) more

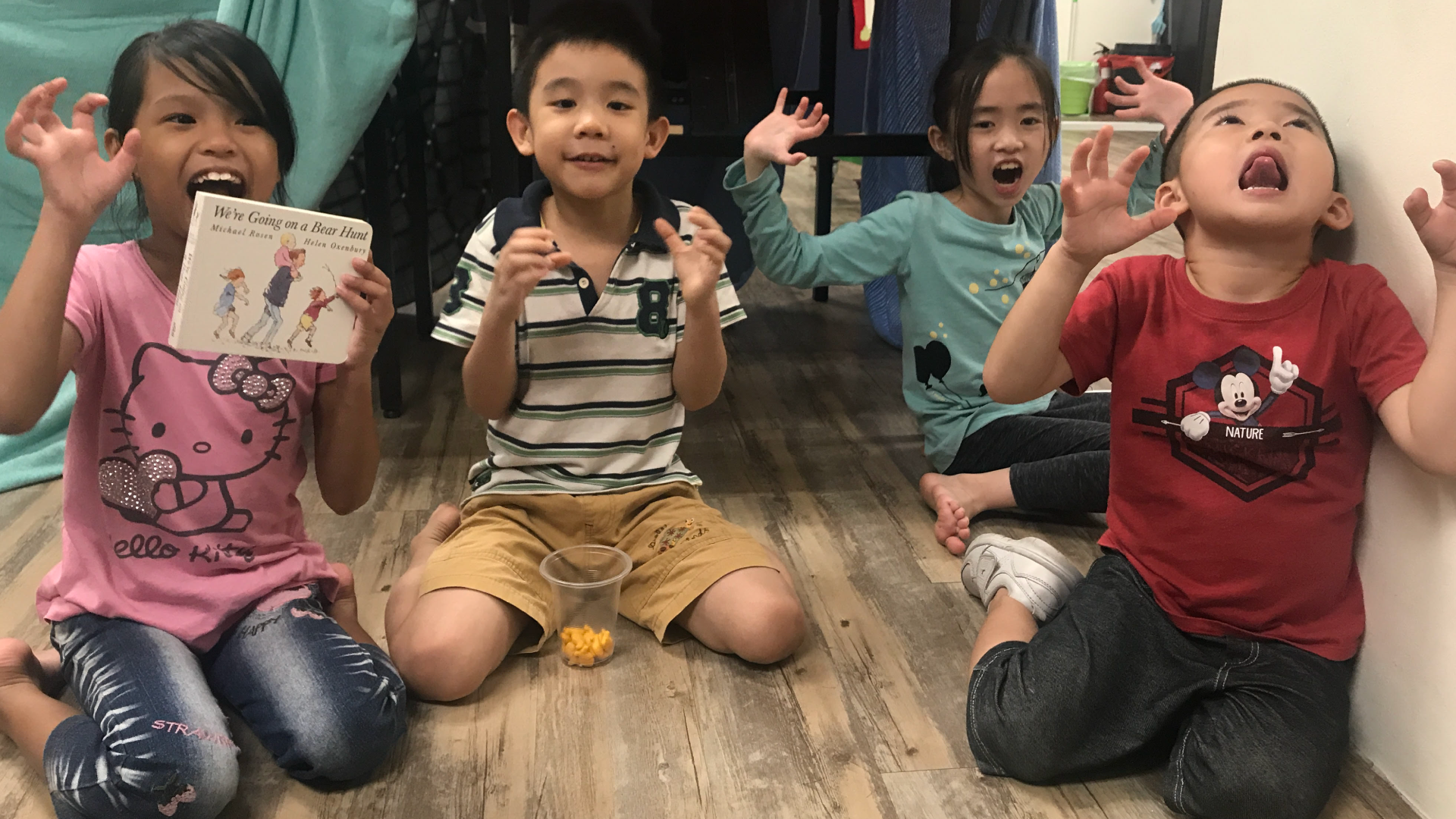

This imperative is certainly in part what drives Chong and her friends to expand the ReadAble project to migrant mums as well, especially considering how much they have inspired her personally.

The migrant mothers Chong met in Jalan Kukoh live with young Singaporean children and without their Singaporean husbands (either because of crime or death). They are an extremely marginalised group in Singapore, she adds — they often can’t speak English and cannot find work due to their immigration status.

But the great lengths they go to in order to give their children a good life were what truly moved her, especially to learning English — one mom, in a bid to give her child spelling tests, did so by Googling the word and pressing the audio button.

It was examples like these, with others who faced immense difficulty and tribulations raising their children, that moved her to think about any and all means of helping them.

And so by teaching them how to read, the migrant mums she and her friends helped can read letters from their children’s schools and government agencies, fill out forms and even help to drill their kids in spelling.

[related_story]

The power of community

From her time volunteering at Jalan Kukoh, one of Chong’s biggest takeaways is that it is quite a neglected neighbourhood.

“People who are poor feel very isolated… They feel people don’t care about them. And Jalan Kukoh is surrounded by rich people, but a lot of people don’t know they exist! (Residents here) don’t feel like they are part of society.”

Yet, she wholeheartedly believes that “very small changes can have huge effects” in addressing social inequality in Singapore:

“If poverty comes from exclusion, the solution to that is inclusion…We wanted to form a community, where the parents, children and volunteers are working together.”

As a project about inclusion, ReadAble also goes beyond just teaching people to read. Everyone involved — volunteers, children and mothers — share their lives with one another.

It is a community of friends and strong social bonds forged that do their tiny part in mending the rifts social inequality creates, too — Chong shares she was once very moved to hear from a mom that she was regarded as family.

“I often tell the moms whom I know through this work, that we are all friends. It is a privilege that I would be the first person they contact when they are going through difficulties, whether it is a phone call to me at midnight when their electricity has been cut off, or a text when they find out their kid has dyslexia.”

And certainly, Chong hopes the project will grow beyond Jalan Kukoh, and to inspire others to “use [their] model to go into other neighbourhoods.”

Even though social equality is still a distant dream, the perhaps idealistic Chong continues to hold great hope for her cause.

“The world is changing. The things that hold women back don’t have to hold us back anymore.”

Keep up to date with Amanda via her Facebook and Instagram.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.