The Occupation was a dark period in Singapore's history and this year marks the 75th anniversary of its start when Singapore fell to the Japanese in 1942.

Throughout the Occupation, Japanese imperialist ideals were imposed on the local population through extensive propaganda campaigns.

One key idea which the Japanese tried to make people believe was that they were freeing the locals from their Western colonial masters under the concept of the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".

This was done in hopes that the locals would become more accepting of Japanese control.

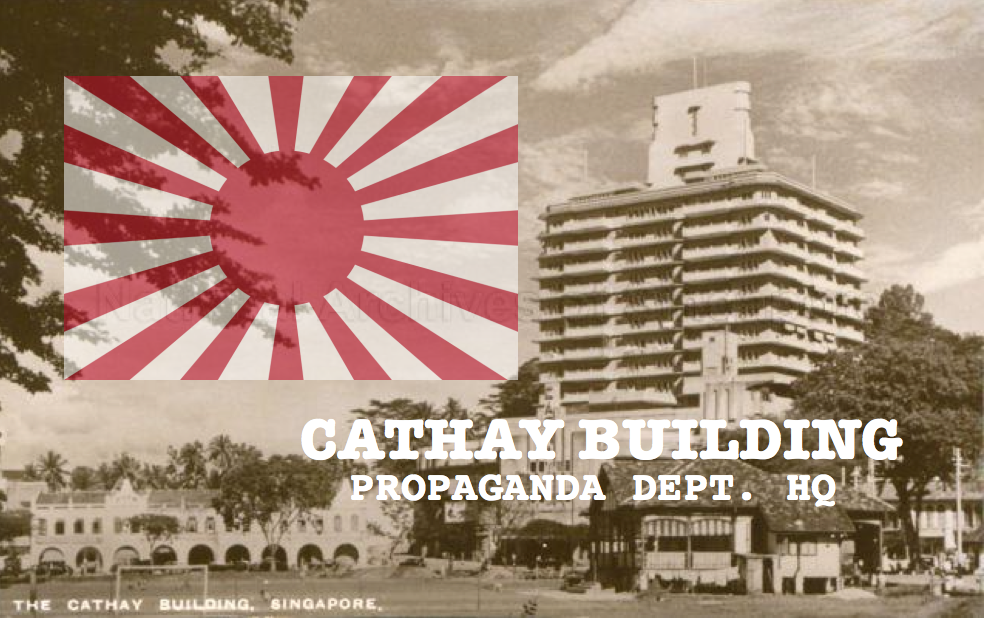

Japanese propaganda in Singapore

For that purpose, the Japanese set up the propaganda department or Hodobu. Its headquarters was located within the Cathay Building.

Photo from NAS

Photo from NAS

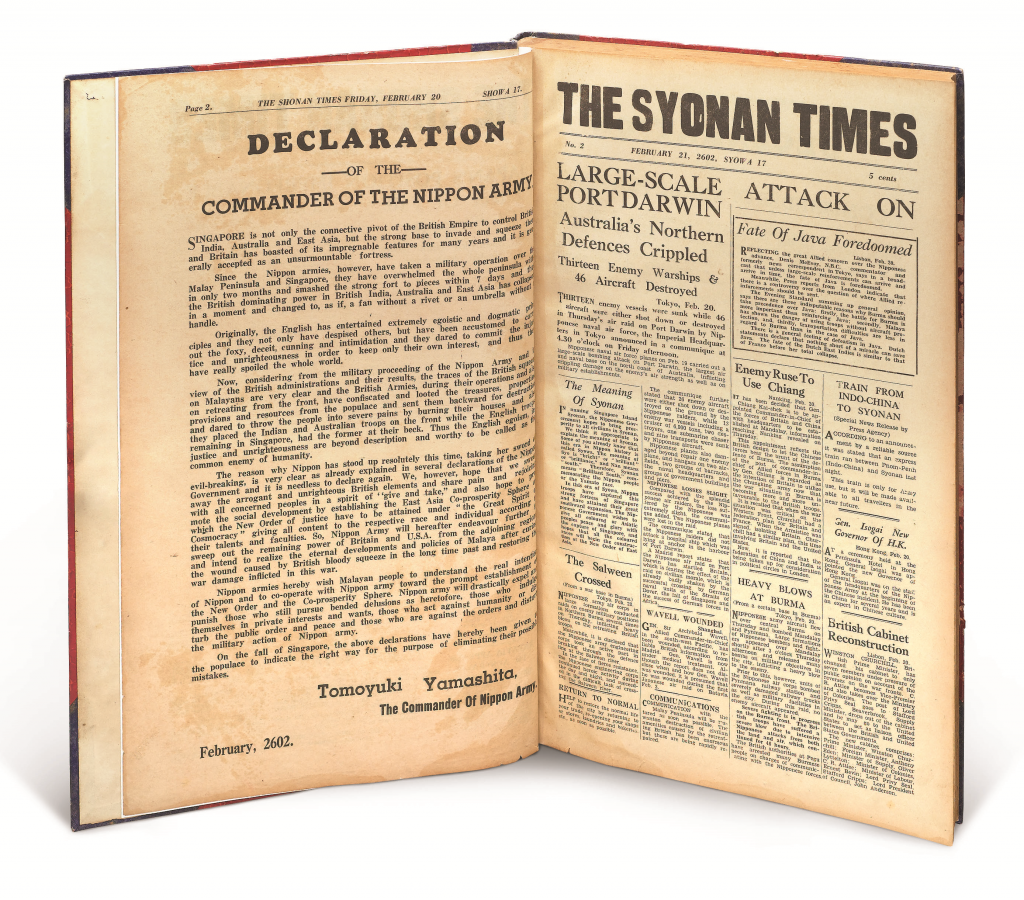

Singapore was a regional distribution centre for Japanese-produced news and magazines, and print was a major channel that the Japanese used to communicate their lies propaganda.

The Cathay Building was home to two Singapore-based dailies -- Syonan Shimbun and a Chinese edition called Zhao Nan Ri Bao.

Photo from NLB via Biblioasia

Photo from NLB via Biblioasia

Working as an editor for the Japanese

During the Occupation, Lee Kuan Yew joined the Hodobu in 1943 as an English-language editor. He was tasked to run through the cables of Allied news agencies.

According to Lee's account in The Singapore Story, cables were sent out in morse code and intercepted by Malay radio operators. His task was to piece the information from the cables:

"I had to decipher them and fill in the missing bits, guided by the context, as in a word puzzle. The cables then had to be collated under the various battle fronts and sent from the top floor of Cathay Building to the floor below, where they would be revamped for broadcasting."

The working hours were also tough. Editors had to work either from 7pm to 12am, or from 12am to 9am (with a 2-3 hour break in between).

[related_story]

Psychological implications

Despite the odd hours, the job's difficulty actually laid in its psychological implications, especially with the much feared Japanese military police known as the Kempeitai lurking and ready to arrest anyone remotely suspicious.

While Lee received news from Allied news agencies that the tide of the war was turning against the Japanese, such information was never allowed to reach the population:

"For hours my head would be filled with news of a war that was going badly for the Japanese, as for the Germans and Italians. But we talked about this to outsiders at our peril. On the ground floor of Cathay Building was a branch of the Kempeitai. Every employee who worked in the Hodobu had a file. The Kempeitai's job was to make sure that nobody leaked anything."

Watched by the Kempeitai

As Lee became more privy to the tide of the war via his job, he became concerned that Singapore would become a key battleground when the Allies attempted to take back the island.

So he resigned from the Hodobu after 15 months, and hoped to take his family to a more rural place in Malaya that was less likely to experience fighting. Cameron Highlands was one of his choices.

But he changed his plans after finding out that he was not spared from surveillance by the Kempeitai after resigning from the Hodobu. Lee was tipped off that the Kempeitai had singled him out:

"As I took the lift down in Cathay Building the day before I stopped work, the lift attendant, whom I had befriended, told me to be careful; my file in the Kempeitai office had been taken out for attention. I felt a deep chill. I wondered what could have provoked this and braced myself for the coming interrogation."

It was a harrowing experience for him as he was watched by the Kempeitai:

"Day and night, a team tailed me. I went through all the possible reasons in my mind and could only conclude that someone had told the Kempeitai I was pro-British and had been leaking news that the war was going badly for the Japanese, and that was why I was leaving. At least two men at any one time would be outside the shophouse in Victoria Street where we stayed after moving from Norfolk Road.

And he lived in fear that he would be captured and tortured:

...At times, in the quiet of the early morning, at 2 or 3 a.m., a car would pass by on Victoria Street and stop near its junction with Bras Basah Road. It is difficult to describe the cold fear that seized me at the thought that they had come for me. Like most, I had heard of the horrors of the torture inflicted by the Kempeitai."

Fortunately for Lee, the Kempeitai did not arrest him, and the surveillance stopped after two months. He spent the rest of the war as a broker on the black market in Singapore.

Top photo adapted from NAS and Wikipedia.

[related_story]

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.