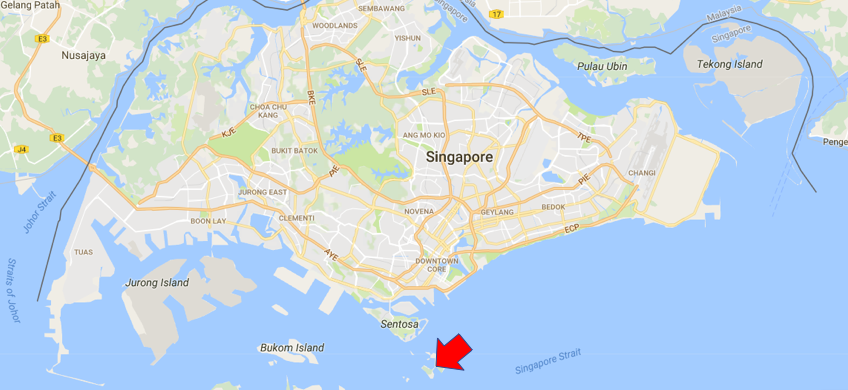

St. John's Island is located approximately 6.5 km to the south of Singapore.

We associate the island today with picturesque beaches, holiday bungalows and picnic grounds. In 2002, it also became home to the St John's Island Marine Laboratory for marine science research.

Source: Google Map

Source: Google Map

This is how it looks like today:

Photo from Singapore Island Cruise

Photo from Singapore Island Cruise

Photo from Singapore Island Cruise

Photo from Singapore Island Cruise

Perhaps unknown to many, beneath the scenic tranquility of the island lies a history of drugs, disease and detainees.

Housing the diseased (late 1800s to 1930s)

In 1819, St John's Island was the site of Stamford Raffles' anchorage before his historic meeting with the Temenggong to establish Singapore as a British colonial port.

After the establishment of the port, immigrants flocked to Singapore in search of better economic prospects.

As the immigrants arrived in droves, some brought along diseases.

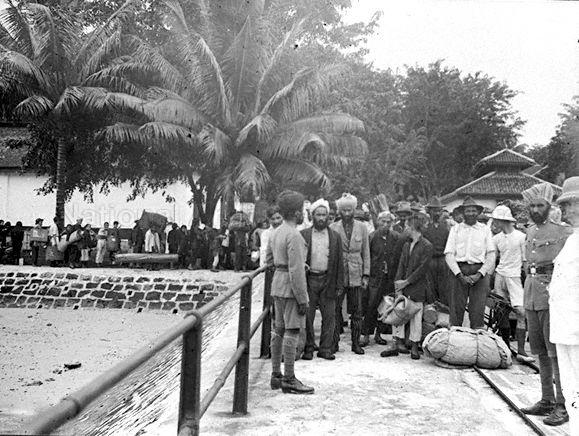

In 1873, a cholera epidemic necessitated the colonial authorities to introduce port health controls on immigrants and ships. St John's Island was made a screening and quarantine centre for this purpose.

Immigrants at the screening and quarantine station at St John's Island in the 1880s. Photo from NAS

Immigrants at the screening and quarantine station at St John's Island in the 1880s. Photo from NAS

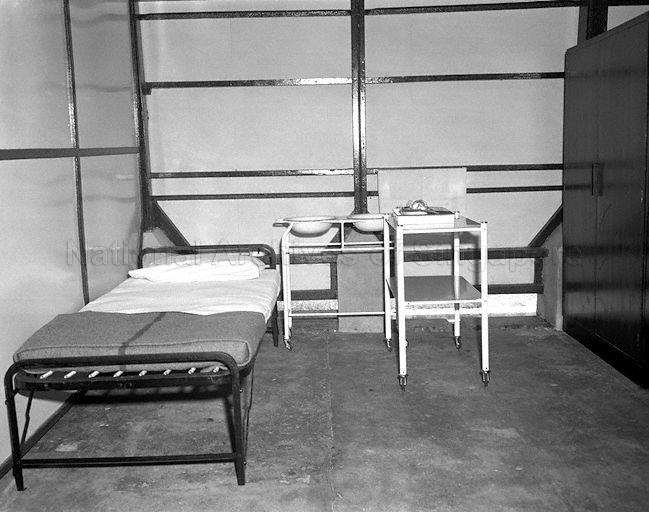

This was what the quarantine quarters looked like in the 1880s:

Photo from NAS

Photo from NAS

Eventually, St John's Island also became a housing centre for sufferers of diseases such as beri-beri and leprosy.

Many immigrants went through the island's quarantine station, and by the 1920s, it had become one of the largest in the world with a maximum capacity of 6,000.

Its reputation grew, and about a decade later, the island became a world-renowned station for screening Asian immigrants and pilgrims returning from Mecca.

Prisoners' settlement (1940s to 1975)

When the era of mass immigration ended, St John's Island's purpose shifted.

During the Japanese Occupation, the island was used to house Prisoners of War (POWs).

After the Second World War, the colonial government used the island to house political detainees and ringleaders of secret societies.

Among its political detainees was S'pore's labour movement pioneer Devan Nair, who was housed there from 1951 to 1953 for his involvement in anti-colonial activities. He would later become Singapore's third president from 1981 to 1985.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="208"] Devan Nair. Source: Istana website[/caption]

Devan Nair. Source: Istana website[/caption]

Another famous detainee was People's Action Party (PAP) co-founder Samad Ismail, who was also assistant editor of Utusan Melayu.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="503"] Samad Ismail. Source: Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation[/caption]

Samad Ismail. Source: Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation[/caption]

As a detainee, Samad's lawyer, Lee Kuan Yew (LKY) paid a visit to him in St. John's Island. According to LKY's memoirs, The Singapore Story, Samad was housed in a bungalow that housed political detainees. It was ringed with chain-link topped with barbed wire.

Drug rehabilitation centre (1955 to 1975)

In the 1800s, there was a thriving opium trade and opium addiction was widespread in Singapore, especially among the Chinese.

By the 1900s, however, there was an emerging debate surrounding ethical and economic considerations of the opium trade in both Europe and Asia. In response to these sentiments, and as an acknowledgment of the harmful effects of opium, the colonial government began to reduce and control opium consumption.

The possession of opium and the tools for smoking it became illegal under the Opium and Chandu Proclamation in 1946.

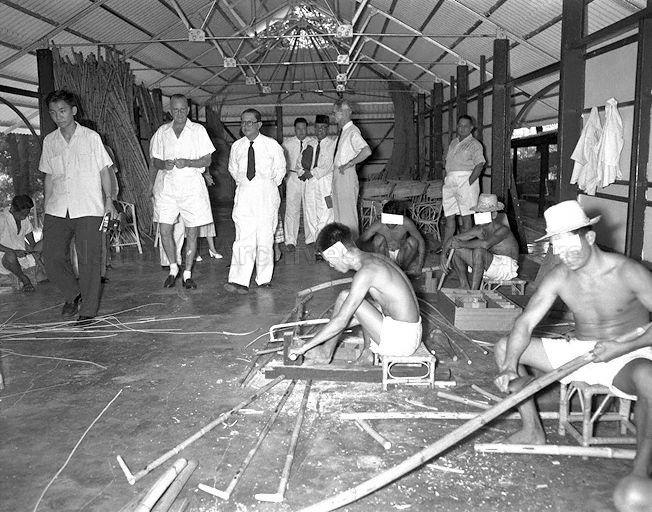

In 1955, the Opium Treatment Centre opened on St John’s Island for treating opium addicts. The treatment facility served the second phase of a three-phase rehabilitation process of the era: withdrawal, rehabilitation and re-integration.

Photo from NAS

Photo from NAS

The centre went beyond just keeping individuals away from opium. Through occupational therapy, addicts were given tasks or skills, such as carpentry, rattan work or tailoring, to learn. This enabled them to find work and re-integrate into society after their release.

Photo from NAS

Photo from NAS

Photo from NAS

Photo from NAS

After years of being a place for quarantine, incarceration, and rehabilitation, St. John's Island was made a place for holidays in 1975.

Today, some of the buildings, such as the old drug rehabilitation centre and old bungalows, still remain, but they no longer have the same purpose as before. Nonetheless, they serve as a reminder of the island's past.

Top image from Google Street View.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.