What makes a person an artist?

Is it their talent? The fact that they make a career of it? Or even a formal education in an artistic discipline that translates into pursuit of it in a full-time capacity?

We thought we had the answers, until we met Yip Yew Chong.

You see, Yip is a Singaporean, as ordinary as we come.

He followed the mainstream academic system the nation upholds and which any set of traditional parents would be proud of: Pearl's Hill Primary School (now replaced by Hotel Re!), Raffles Institution and Raffles Junior College, Accountancy graduate at Nanyang Technological University.

He even has a reasonably mainstream profession now: he's an accountant. Precisely what his 15 years of formal education prepared him for.

Despite this lifelong conventional path, Yip, now 48 years old, has since 2015 created beautiful, very accessible wall murals in various places around Singapore, like this:

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

And this:

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

And this, at Everton Road:

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

As well as these, part of a series he did in Tiong Bahru:

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

All this, with no formal training whatsoever.

But it would be unfair for us to claim he got here from scratch, doing absolutely nothing before his first of these murals, "Amah", which he did in August 2015:

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Because, as we found out when we sat down with Yip during his lunch break at a couple of modular cube benches at the National Museum, where his latest creation is displayed (pictured at the top of our story), he has dabbled in art, almost continuously and in various forms, since his childhood.

Always drawing

Photo by Joshua Lee

Photo by Joshua Lee

It started in kindergarten, Yip struggles to recall. He remembers using pencils, crayons and colour pencils, working on scenes like going to the beach, and drawing people with stickman-style shapes and faces to begin with.

"I think I applied colours more brilliantly than most people. That was what stood out. In primary school I was one of the rare members in the arts club... and there was one art teacher who was very passionate about what I do."

His parents, he says, didn't focus too much on his talent, so he worked with the usual supplies they bought for the family for school from "the bookstore on the street" near their home.

But his first art competition they sent him for was in 1976, one that was held in conjunction with the opening of People's Park Complex. He was in Primary 1, and drew a series of colourful lights on the ceilings where there was a large podium using magic markers — a tool he is still happy to employ today, by the way — but couldn't finish his piece within the two or three-hour window allocated.

Yip didn't lose heart, though, thankfully — he would go on to do much more than drawing. Still in primary school, he crafted lanterns for Teachers' Day, created chalk drawings on the blackboard and even made and painted a styrofoam sculpture for its 100th anniversary when he was in his final year there, all while being in art club.

In Raffles Institution, he opted for the parent-pleasing science track, but continued his artistic exploits.

It was in fact here that he painted his very first mural, also with the school's art club — an underwater scene on a 50-metre wall at RI's swimming pool, at their previous location on Grange Road.

Yip's vertical painting continued with vast backdrops done for the school's drama club productions, and he would go on to do this in RJC, and also at NTU, where he spent three years studying accountancy.

National Service didn't stop him, either — he worked with his superior on this epic dragon sculpture for a graduating dinner event:

Photo courtesy of Yip Yew Chong, via his site. Yip's on the far left, at the dragon's tail.

Photo courtesy of Yip Yew Chong, via his site. Yip's on the far left, at the dragon's tail.

Then, life happened

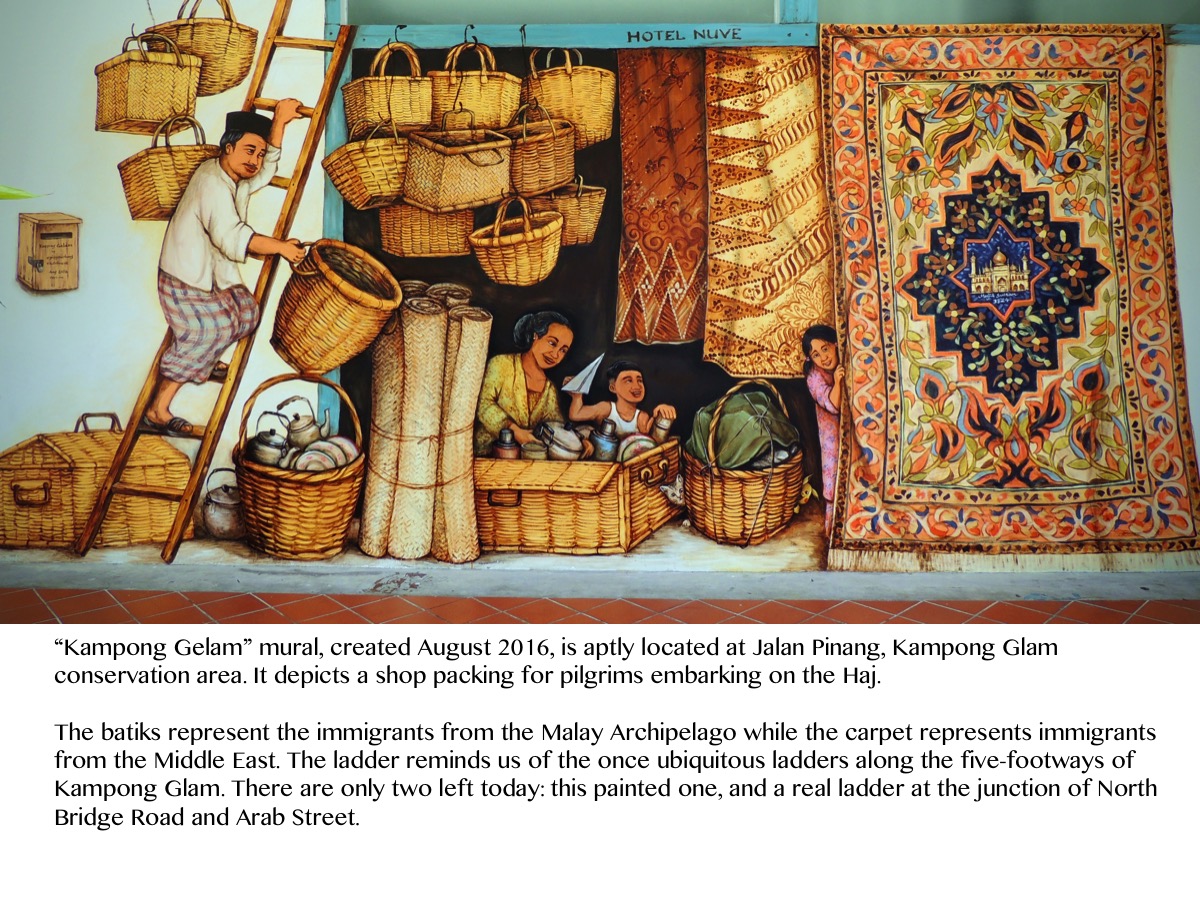

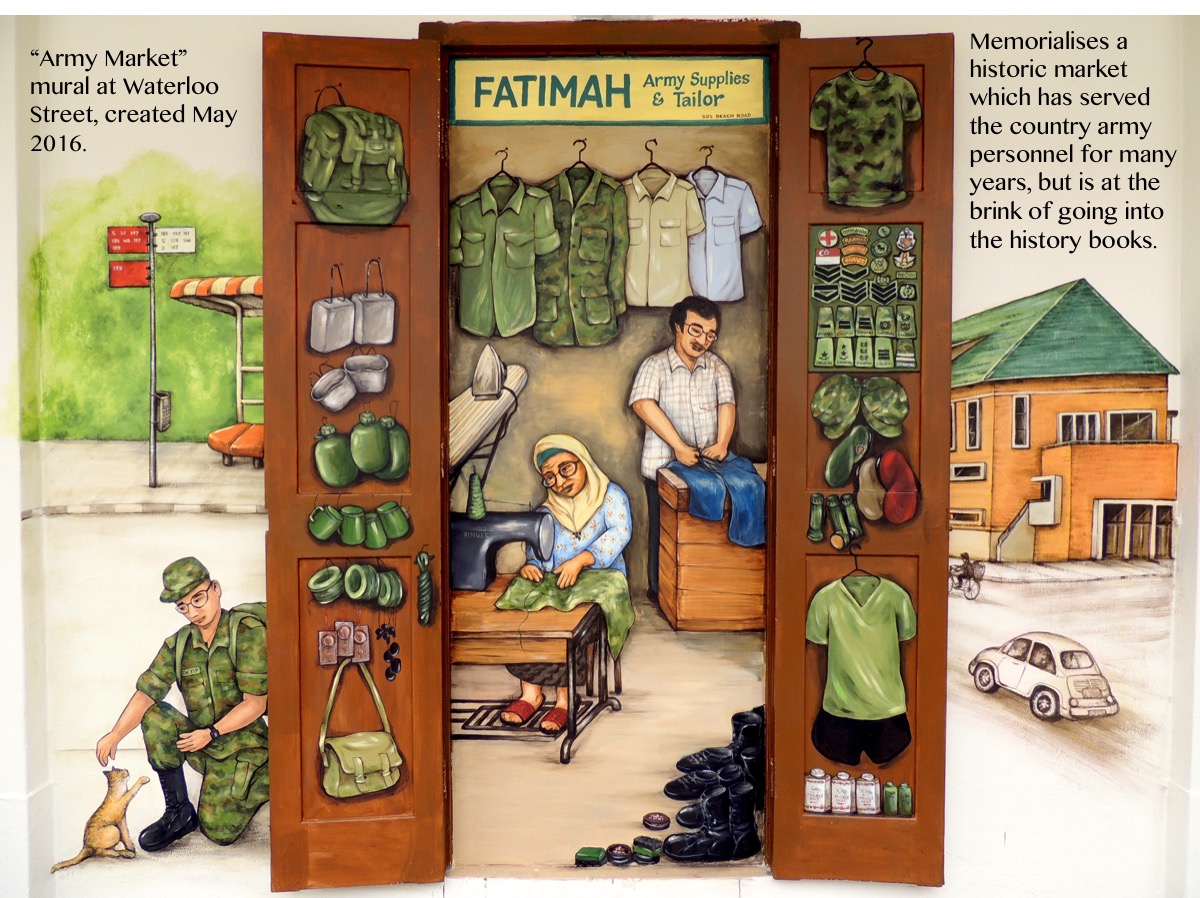

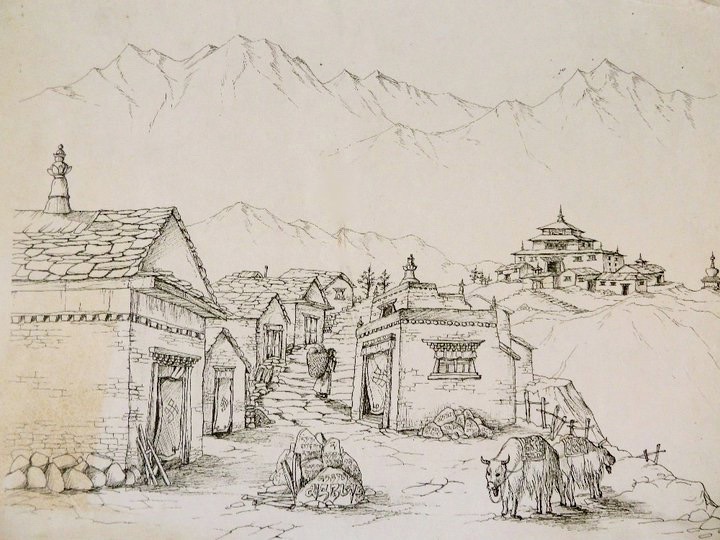

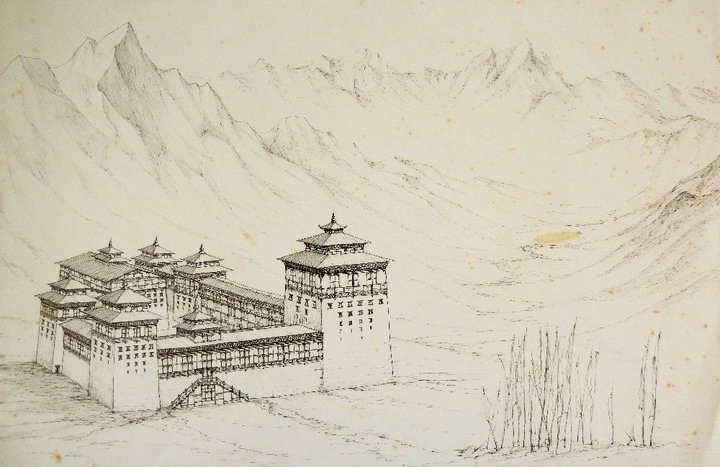

"A romanticised depiction of Thyangboche, a mountain village about 3 to 4 walking days from Everest Base Camp." Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

"A romanticised depiction of Thyangboche, a mountain village about 3 to 4 walking days from Everest Base Camp." Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

As with many Singaporeans who might have started out with a certain interest in some kind of art, but had to abandon it as "life" took over, Yip's experience is a classic tale of Singaporean "life happening".

After graduating from school, Yip's backdrop painting, sculpting and general artistic activity took a backseat, although before getting married, he snuck in the occasional sketch of scenes he recalled fondly from his travels.

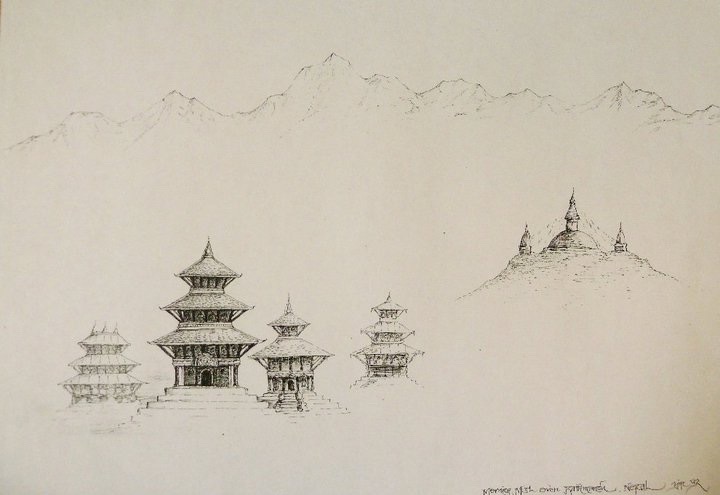

Like this one from his first trip to Nepal in 1990:

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

In a caption to this, he writes:

"Here, I imagined the Kathmandu valley being shrouded in a thin veil of morning mist, exposing only the top of the monkey temple hill, with the medieval city in the foreground."

And this, too, a scene from a palace in Bhutan — a place Yip had never been to, and drew before realising where it actually was:

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

Photo via Yip Yew Chong's site

From there, Yip was largely busy getting busy with his work and with starting a family — his son is now 20 and a full-time national serviceman, while his daughter is 18, and is studying in an arts and humanities course. His wife, meanwhile, has been a homemaker.

He said no matter what his children choose to do, though, he'll be supportive.

"Nowadays doing humanities has more options than in my time. Doing humanities was, sad to say, harder to find a job; that kind of mentality. Now it's different."

Painting heritage-themed murals around Singapore was something Yip wanted to try about two years ago, and that's what culminated in Amah, the first of his public murals in recent years.

Clad in a T-shirt, shorts and slippers on most occasions, Yip took to the wall (on weekends and public holidays only, mind) — his blank canvas — with brushes, cans of emulsion paint, as well as acrylic paint for the finer details.

"They approach me and ask what are you doing. A common question: you have permission? In the early days, they will ask. Then I say, 'Yeah, yeah I have permission.'"

These days, though, with plenty more publicity and attention given to his work online, Yip said people were mostly happy when they came across him working, and their positive reactions to him continue to take the humble man by surprise:

"They say very appreciative words, which is nice. People come up to me and, 'oh you're making everyone in the world happy.' And I'll say, oh thank you. Some will say, 'my dental clinic is just down there. Next time you come I give you a free treatment'. Some people will tell me about how happy he or she is when looking at the murals. It feels strange to me when I hear that."

But why heritage?

Photo by Yip Yew Chong, via his site

Photo by Yip Yew Chong, via his site

Something he feels as passionately about apart from art is the urgent need to preserve Singapore's natural and cultural heritage, memories and our past — that in turn, being something Singapore has never been all that good at.

In fact, he's been a member of one of Singapore's most established civil organisations — the Nature Society of Singapore — and has been serving as its treasurer for the past three years.

"Singapore is moving really fast. Too fast that some of the things got bulldozed along the way. Only years later we regret and rebuild, recreate...

For example, we've built the Bukit Timah Expressway in the middle of the forest. What do we do now? We try to bridge it with the bridge. The eco-bridge. The eco-lane. To link the animals' movements and plants' movements... We destroy, only to recreate many years later."

Photo by Yip Yew Chong, via his site

Photo by Yip Yew Chong, via his site

"I think education to the public, especially the younger generations, of not just the superficial of 'appreciate this plant or that animal' but really have an understanding of the whole ecosystem and the habitat. How the habitats actually work together. That's important.

Otherwise youngsters may just, 'okay this animal is very cute or that plant is very nice...' Not enough. If they understand the whole habitats and that habitats cannot be fragmented... They cannot survive as fragments. That's important. Which is what Nature Society is also trying to do. Which is to promote and appreciation of not just the individual flora and fauna but the whole habitat, how habitats can survive. Not as fragments."

Singapore, a part-time art culture?

Photo by Chiew Teng

Photo by Chiew Teng

Perhaps Yip's is one journey an artist (or aspiring one, for instance) in Singapore often finds themselves having to take — keeping it as a co-curricular, worked on when there are pockets of time outside of a "real job".

Even now, some 25 public murals later, he's still a part-timer — he works on murals only on weekends, and sometimes during lunch hour, like the time he spoke with us.

We asked him if he felt like he would have pursued the arts as a career if those options were available to him back then — he said perhaps, but back then, there weren't:

"My first break was in 2005 after 10 years of working. (By then) There's no need to go overseas to study film anymore. I didn't really want to go full force into this. I wanted to keep my accounting profession. So I just took short courses and self-learn so I went to the Objectif."

This situation isn't ideal, let's face it: we all want a thriving arts culture in Singapore, where talented folk can channel all their energies into pursuing their craft — be it in dance, painting, literature, singing, composing and producing music, beatboxing, theatre, or anything else — and turning it into a sustainable, full-time career.

[related_story]

Any arts practitioner will know that the best way to hone one's craft and truly have any semblance of hope to emerge as recognised or great is to devote all his or her time to it. Most also at some point determine the need to venture overseas to pursue it further: think of beatboxer Dharni in Poland, our dancers and ballerinas who go overseas on arts scholarships (or not) to train and join companies professionally, our singers, actors and actresses who go big in Malaysia, China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, and our visual artists who exhibit overseas. Even our filmmakers.

But perhaps, for people like Yip who don't necessarily aspire to those heights (meaningful, significant and a huge source of Singapore pride as they all are, undoubtedly), pursuing one's passion on a part-time basis could truly make all the difference, even if it's just to bring joy, delight or nostalgia to Singaporeans or people who see his work.

Top photo via Yip Yew Chong's mural blog

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.