Following our story on Punggol Zoo, one of Singapore’s earliest zoos opened by “Animal Man” William Basapa, publisher NUS Press informed us that Botanic Gardens once housed fantastic beasts in a zoo.

No, it wasn't kept in some magical suitcase located at the Gardens where one could climb into to see the animals. There were also no nifflers, bowtruckles, erumpents, demiguises, occamies, and thunderbirds.

It was a traditional real-life zoo

The Botanic Gardens’ zoo had operated many years before Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them was published in the Harry Potter series. It was also established before Punggol Zoo.

According to the book Nature’s Colony by Timothy Barnard (were you expecting Fantastic Beast and where to find them by Newt Scamander?), the Botanic Gardens’ management first raised the idea for the zoo to the British colonial government in 1870.

Five years later, in May 1875, the zoo was formally established within the Gardens’ premises with the gift of a female Sumatran rhinoceros by the then Governor of the Straits Settlements, Andrew Clarke (best remembered in the name Clarke Quay). The gift of various animals followed, and the zoo’s collection grew.

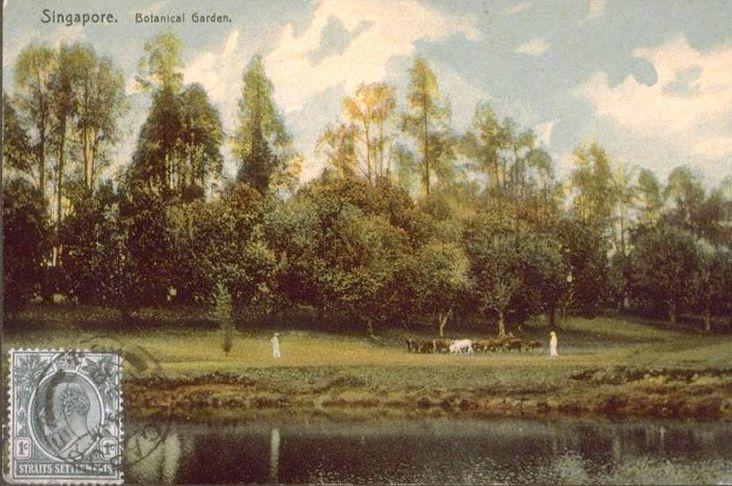

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="732"] Botanic Gardens in 1900. Source: National Archives[/caption]

Botanic Gardens in 1900. Source: National Archives[/caption]

Fantastic beasts in the Botanic Gardens

By 1877, there was a total of 144 fantastic beasts at the zoo. Most were wildlife that could be found in region. However, there were gifts of animals from as far away as Australia too. Some of the animals included in the collection were tigers, kangaroos, monkeys, emus and many other birds.

Among the famous animals at the zoo were neither a niffler nor murtlap. Instead they were a baby kangaroo, which won the crowd whenever it peeked out from its mother's pouch, and a Malayan tapir owned by the Garden's director, Henry Ridley.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="940"] Source[/caption]

Source[/caption]

The zoo grew to be a popular attraction among the locals. As Barnard notes in Nature's Colony:

The animals that were present in the zoological menagerie at the Singapore Botanic Gardens became a primary attraction for the general public. As one late-19th-century guide to Singapore described the site, the visitor would see, "on the shoulder of the hill", a small aviary and monkey-house where specimens of some of the rarer birds, beasts and reptiles of the Straits and neighbourhood are on exhibition." More importantly, the animals attracted non-elite visitors to the Gardens, who were fascinated with the range of animals on display. One visitor in 1875 commented that the newly arrived Australian animals were "sources of endless admiration and amusement to the Malays and Chinese." A young kangaroo was a particular favorite. Whenever it peeped out of its mother's pouch, it "took the popular fancy immediately."

The zoo animals were as prone to becoming crime victims as fantastic beasts were to being misunderstood by wizards/witches

Just as there are cat killers today, there were also crazy animal killers in the past.

In February 1876, someone sneaked into the zoo and killed several animals, including a large bear, emus, and several kangaroos, which were killed by stabbing. The perpetrator(s) were never brought to justice despite a $50 reward (a very handsome sum in the 1800s) offered for information on the crime.

Some visitors, who were suspected to be unscrupulous animal traders, would also try to steal or kill the animals in order to sell replacements to the zoo.

There were also instances of animal abuse by the zookeepers. One incident saw a drunk Botanic Gardens Head Gardener kicking a python in its head to impress a friend. It ended with the python strangling the gardener, almost killing him.

Having a zoo is nothing like keeping animals in a magical suitcase, or having a niffler that steals gold and other shiny stuff to pay the bills

Like the zoos of today, there were high costs in running the Botanic Gardens zoo. Money was required to maintain and upgrade the enclosures, feed the animals and also to ensure that the premises were secure.

Animals such as the tiger and Sumatran rhinoceros were particularly expensive to feed. The high costs led to the sale of the zoo's collection of carnivores in 1877, merely two years after the zoo was first established. It was probably a financial relief to the management too, when the rhinoceros died in August 1877. Sadly, that same species of rhinoceros is on the verge of extinction today.

The lack of will to maintain the facilities and to care for the animals resulted in the zoo's closure, which was announced in 1904.

Real beasts die and cannot be saved by magic or magical potions. But they can be preserved in some way.

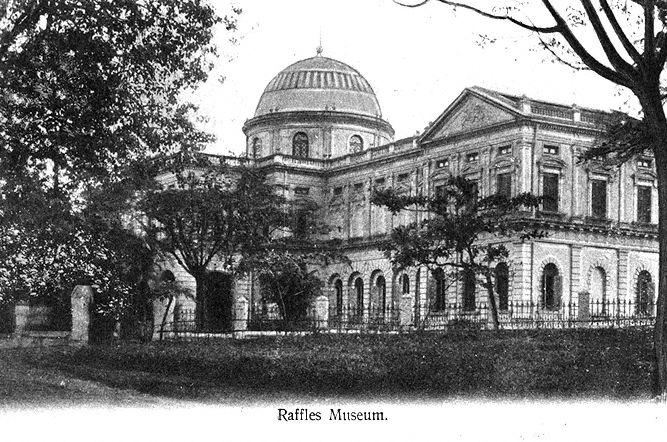

Like the Punggol Zoo later on, the Botanic Gardens' zoo had close ties with the old Raffles Library and Museum (present day National Museum of Singapore).

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="667"] Raffles Library and Museum 1900s. Source: National Archives[/caption]

Raffles Library and Museum 1900s. Source: National Archives[/caption]

In Of Whales and Dinosaurs: The Story of Singapore’s Natural History Museum by Kevin Tan, the zoo was a good source of animal carcasses that would be preserved and added to museum’s collection of specimens. One such example was the donation of the zoo's Sumatran rhinoceros' carcass to the museum after the animal had died.

It was one of the earliest specimens secured to form the beginnings of the museum's natural history collection. Unfortunately, however, there were problems with stuffing the beast, as Tan writes:

Alas, after the museum's taxidermist successfully exracted the skin from the carcass, it was found to be 'in very bad condition' and was 'judged unsuitable for stuffing'. The skeleton, however, was 'very neatly mounted' and put on display by the end of 1877.

In its evolutionary journey into the present day National Museum of Singapore, the old Raffles Library and Museum's natural history collection was hived off, moved around, and almost lost. Fortunately, those who valued the collection's importance fought to preserve it, which led to the establishment of today's Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

Some of the specimens from the Botanic Gardens' zoo have survived into the present day museum.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum[/caption]

Source: Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum[/caption]

Nature's Colony by Timothy Barnard and Of Whales and Dinosaurs: The Story of Singapore’s Natural History Museum by Kevin Tan are available at NUS Press.

Top photo from here.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.