Today social media is so entrenched in everyday life that we simply cannot imagine a day without Facebook's Newsfeed or Snapchat's Stories. We even train ourselves to talk to each other in 140 characters or less.

But it is precisely in this open environment on the Internet that the most exciting drama plays out.

What if social media existed in the 19th century? How would the drama that was Stamford Raffles' life play out if it was out on Twitter? We hazard a guess:

Raffles sat for this iconic portrait by George Francis Joseph in 1817. This oil painting was done when Raffles returned to Britain to publish his book on ancient Javanese history. Look closely and you'll find Asian artefacts, like a seated Buddha statue, in the background.

Since selfies weren't available then, the best way of immortalising his image was to sit for hours for an oil portrait, which was literally a pain in the ass.

Instagram is littered with photos of boarding passes, airplanes, and #wanderlust.

Being the workaholic and ambitious man that he was, we imagine that Raffles' Instagram would be filled with photos of his work trips. His first foray into Southeast Asia started with Penang in 1805. He would spend almost 20 years in the region, hopping between Malaya, Bencoolen, and Singapore.

In December 1818, Raffles set out to look for a new location to replace the port city of Malacca. By end January 1819, Raffles arrived on the shores of Singapura, and negotiated a deal with Sultan Hussein Shah and Temenggong Abdul Raman to set up a trading post (or "factory" as it was the in word back then) on the island.

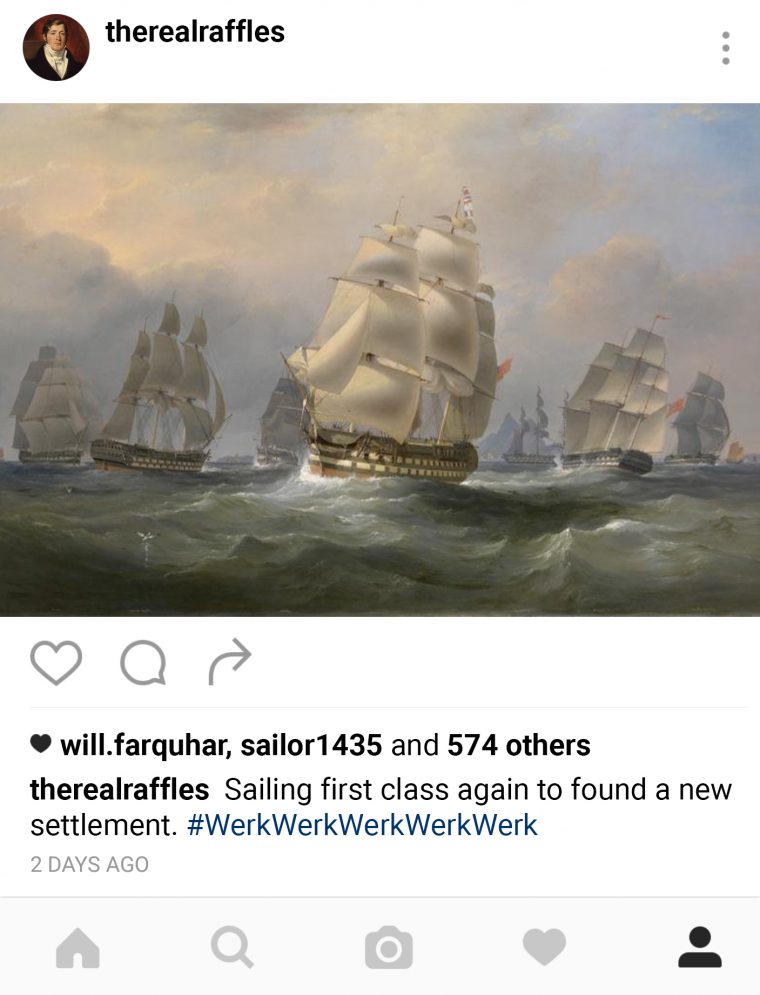

Raffles was a avid naturalist who was fascinated by the world of flora and fauna available on the other side of the world. He often observed exotic animals and plants and commissioned detailed drawings of the natural world to document.

One of these was the Rafflesia, the largest flower in the world. It is a huge, foul-smelling parasitic flower discovered by a local guide hired by botanist Dr John Arnold on an expedition in Sumatra in 1818. Dr Arnold decided to name it after Raffles - for what reason, we would never know.

While Raffles was undoubtedly the founder of modern Singapore, it was his two Residents - first William Farquhar and later Dr John Crawfurd who effectively ran the colony. In many ways, Farquhar and Crawfurd were the pragmatic voices who balanced Raffles' idealistic nature.

Once Raffles got permission to set up a trading port here in 1819, he left Farquhar in charge of running the settlement, only returning a total of three times within the next five years.

While Farquhar turned the settlement into a thriving port town, he deviated from Raffle's plan by allowing gambling dens, slave trading, and other vices - which, while immoral, were good sources of income for the government. Raffles ultimately sacked Farquhar and replaced him with Dr John Crawfurd in 1823.

The avid naturalist in Raffles would sometimes see him resort to less-than-scrupulous means to make sure he gets credited for wildlife discoveries. Animals such as the Tapir, the Dugong, and the Black Hornbill were initially discovered by Farquhar. However, Raffles read Farquhar's account of the animals and sent his own accounts to London to get them published first.

Today, Farquhar's collection of natural history drawings can be found at the National Museum of Singapore.

Five years after Sultan Hussein Shah allowed the British to set up a base in Singapore, Dr John Crawfurd managed to arm-twist him and Temenggong Abdul Rahman into selling the entire island to the British. This contract was called, ironically, the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance.

In return, the Malay chiefs got a lump sum of between 700 and 33,200 Spanish dollars as well as monthly allowances of between 700 and 1,300 Spanish dollars.

The rivalry between Raffles and Farquhar didn't stop when Farquhar left Singapore in December 1823. When Farquhar returned to England, he requested the East India Company to reinstate his command of Singapore - claiming that he was the rightful founder. Unfortunately, his request was rejected.

Nearing the end of his career in 1824, Raffles boarded The Fame, an England-bound ship at Bencoolen (present day Bengkulu, Indonesia). However, minutes after leaving the harbour, The Fame caught fire, destroying all of Raffles' possessions as well as his drawings and research.

Raffles managed to depart Bencoolen successfully two months later and arrived safely back in England. He died two years later in 1826.

Jokes aside, perhaps if social media existed in the past, we might have a more comprehensive idea of our history. At the very least, it would make for a more entertaining read.

Top photo adapted from Raffles' 1817 portrait by George Francis Joseph.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.