Some time back, the Circle Line experienced a host of confusing signalling issues that resulted in repeated stalling and breakdowns across nearly all of its stations.

This was then traced to a rogue train, which was carrying hardware that interfered and cut off the signals being transmitted to the trains around it — essentially "confusing" them. The affected trains then apply emergency brakes and stall, impacting the rest of the system.

If you followed media reports on this, you would assume that the heroes who discovered Passenger Vehicle (PV) 46 were engineers from the Defence Science and Technology Agency (DSTA).

Take this Nov. 11 Straits Times report, for instance:

Screenshot from ST article. Click image to go to article.

Screenshot from ST article. Click image to go to article.

This one, to be fair, was reported directly off this Facebook post from Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen:

Transport correspondent Christopher Tan followed up with this:

Screenshot from ST. Click image to go to article.

Screenshot from ST. Click image to go to article.

But the story still focused on the engineers, with just two short mentions of a group of government data scientists in passing:

Screenshot from ST. Click to view article.

Screenshot from ST. Click to view article.

Thanks to a Medium post on the data.gov.sg blog, though, we now know who the real, unsung heroes behind the solution to the Circle Line's signalling problems turned out to be: a trio of data scientists from GovTech, the new agency formed from the marriage and division of the old MDA and IDA — with the rest of it forming IMDA.

On November 5, the team of Daniel Sim, Clarence Ng and Lee Shangqian took on the task of investigating the cause.

Most of the post would be quite difficult to understand for anyone who has never used the Python programming language, but in layman's terms (or at least whatever we could understand from it), here's how they deduced it was a rogue train:

1. They started with a set of data given to them from SMRT of the spate of incidents of signal loss, which consisted of

a) Date and time of each incident;

b) Location of each incident;

c) the ID of the train involved and

d) the direction the train was headed.

They initially couldn't make sense of any of the data they started out with — the incidents were occurring at all times of the day, and at pretty much all the stations along the line, and affected some 60 trains that serve it.

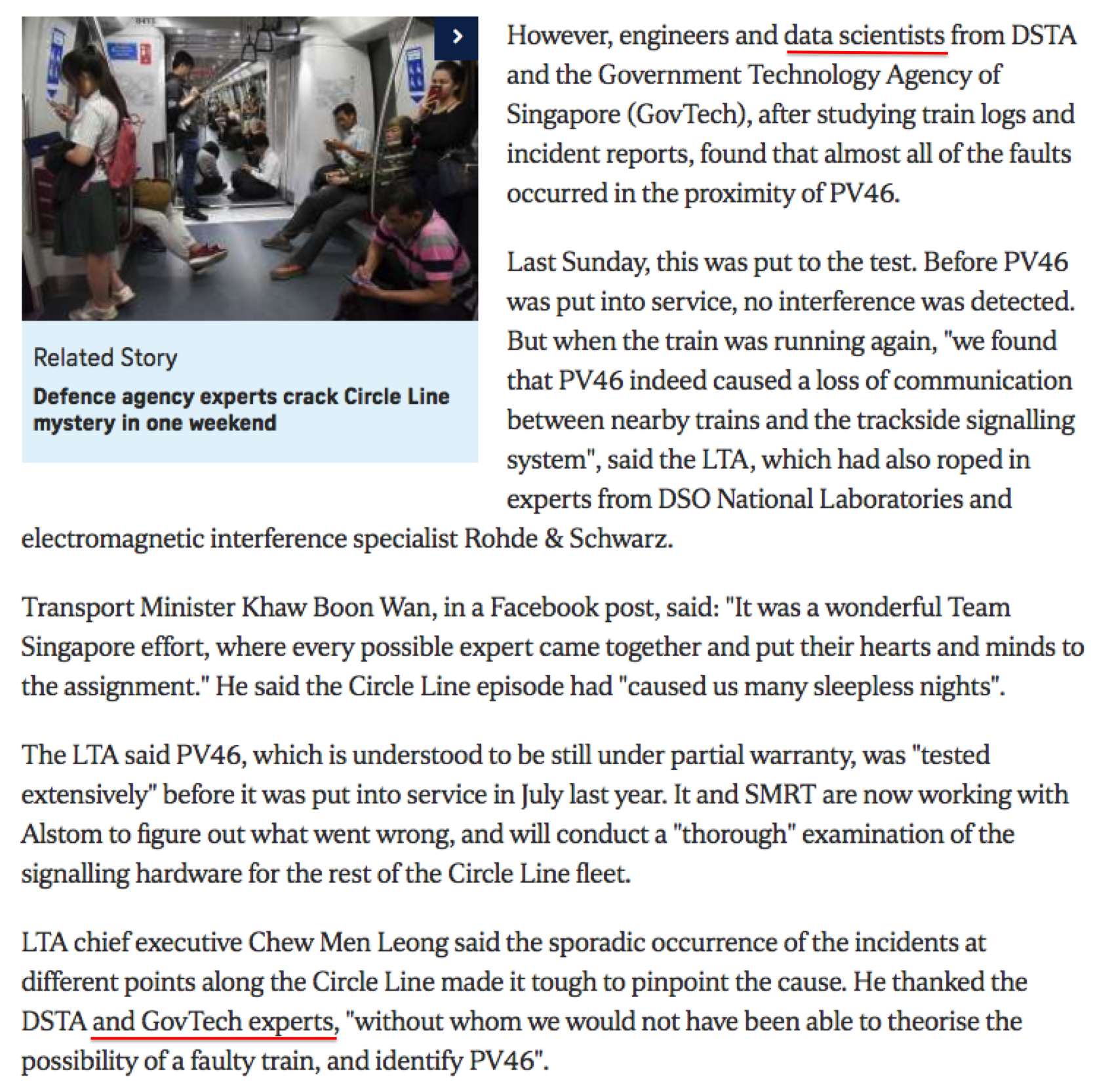

2. Then they received inspiration from something called the Marey chart, which visualises time, location and direction together.

A Marey chart looks like this:

Source: http://mbtaviz.github.io/

Source: http://mbtaviz.github.io/

The vertical axis tracks time, and the horizontal axis tracks the stations, so you'll be able to see where a train is going, and where it is, at any given time of the day.

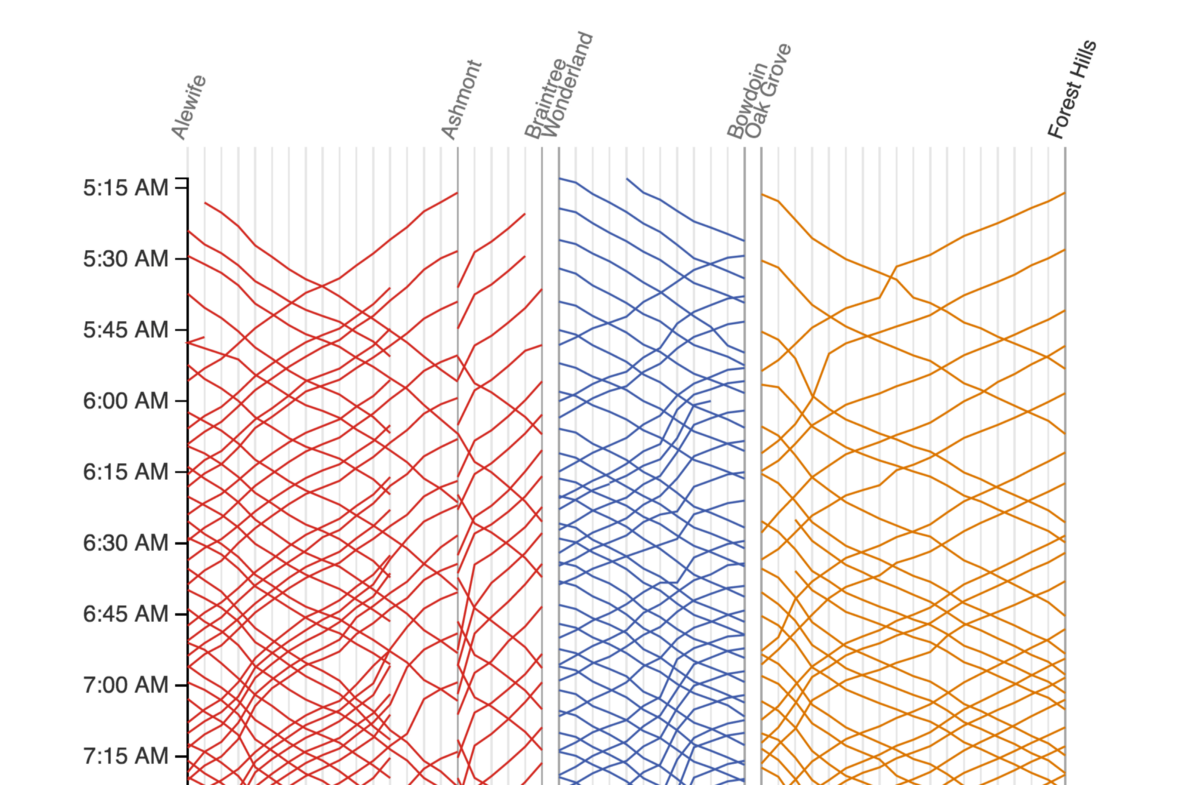

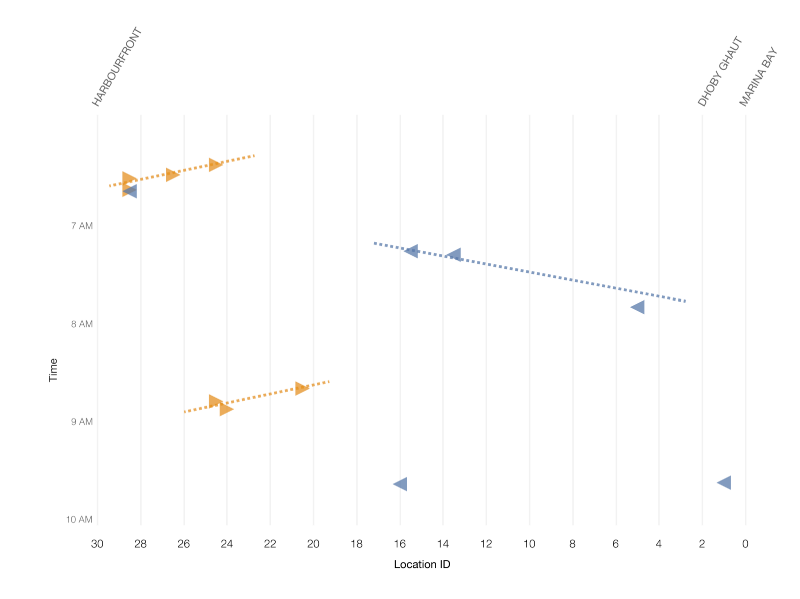

So here's what some of the Circle Line train signal failure incidents looked like, coupled with the directions the trains were headed in when the incidents took place:

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Upon looking closely, the data scientists realised the incidents were happening in quick succession, with the train at the next station behind the first affected train getting hit shortly after the first stall happens.

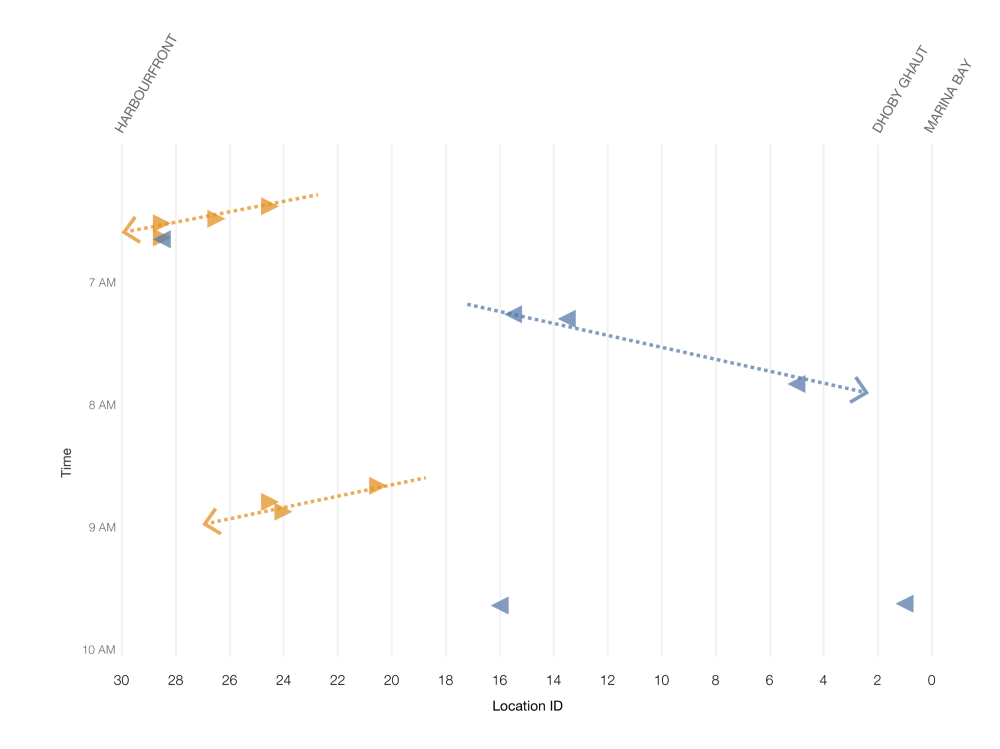

Especially when they drew lines linking them:

Screenshot from data.gov.sg blog post

Screenshot from data.gov.sg blog post

But it still didn't make sense — why were these happening in succession, and almost like a "trail of destruction"?

See how the progression of incidents took place in a reverse direction from which the trains were moving, as time passed:

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

3. That's when the "eureka" moment happened: the hypothesis of a train that is messing up the signals of anyone it passes.

Some complicated number-crunching later, they came to this conclusion:

Of the 259 emergency braking incidents in our dataset, 189 cases — or 73% of them — could be explained by the “rogue train” hypothesis.

Nice. This sounds like this could convincingly be what's happening here.

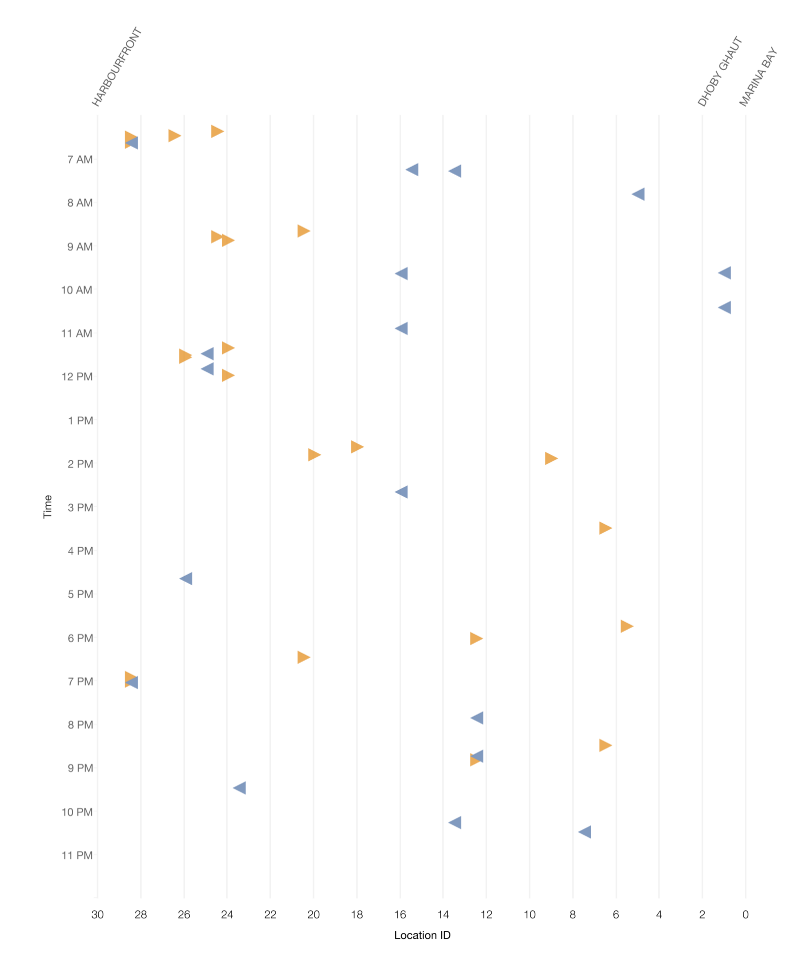

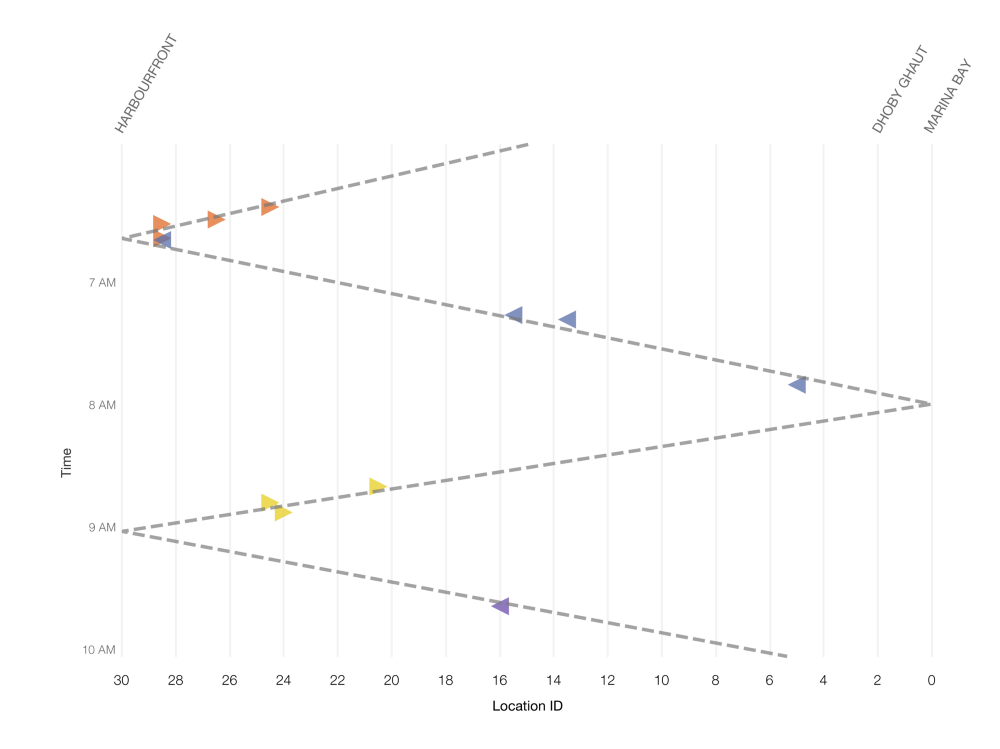

4. The next question then was, how many rogue trains were there? They looked again at the typical path a train takes to complete its entire journey before it's taken out of service:

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Compared with their initial visualisation of this, it seemed to match the path of a single train:

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

5. Then, the team headed to Kim Chuan Depot for some serious overtime work — they had to hunt down the train that was in service and at these spots when the incidents happened.

From the blog post:

After sundown, we went to Kim Chuan Depot to identify the “rogue train”. We could not inspect the detailed train logs that day because SMRT needed more time to extract the data. So we decided to identify the train the old school way — by reviewing video records of trains arriving at and leaving each station at the times of the incidents.

At 3am, the team had found the prime suspect: PV46, a train that has been in service since 2015.

The LTA and SMRT then tested the train and found that indeed, it was causing all the problems — after processing the data, Sim, Lee and Ng found that more than 95 per cent of the 200 incidents that happened between August and November were caused by this single train.

The remaining 5 per cent, Sim wrote, were likely normal instances of signal loss that happen occasionally.

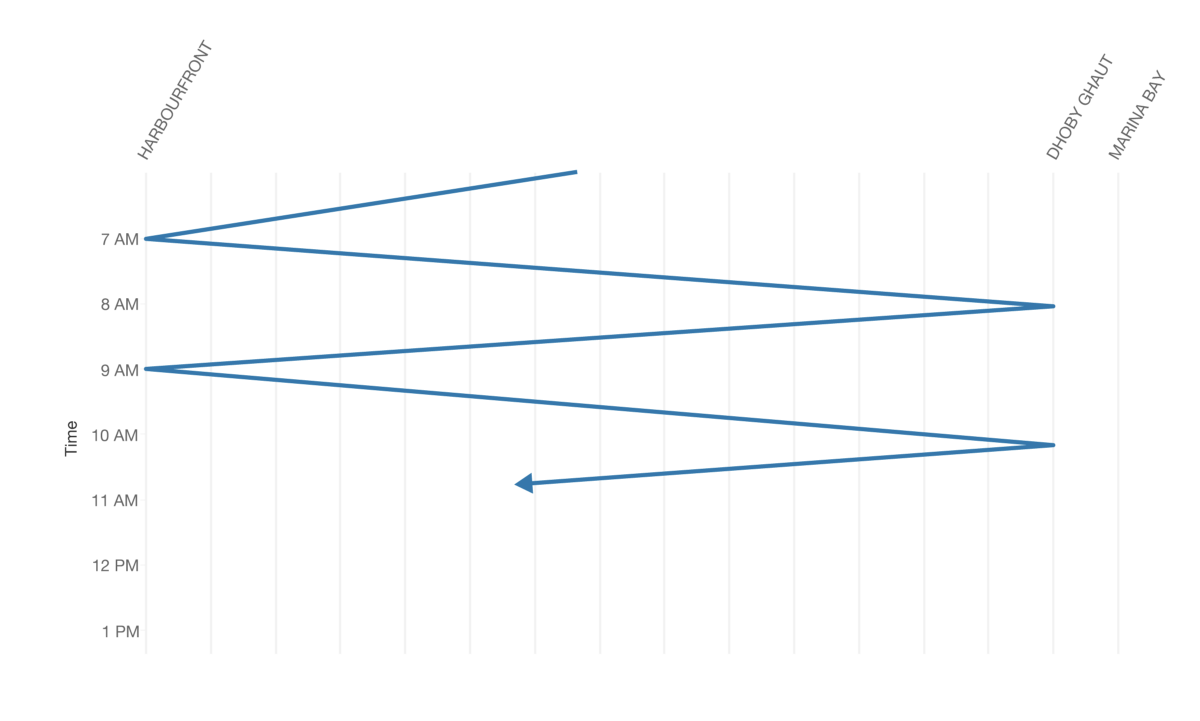

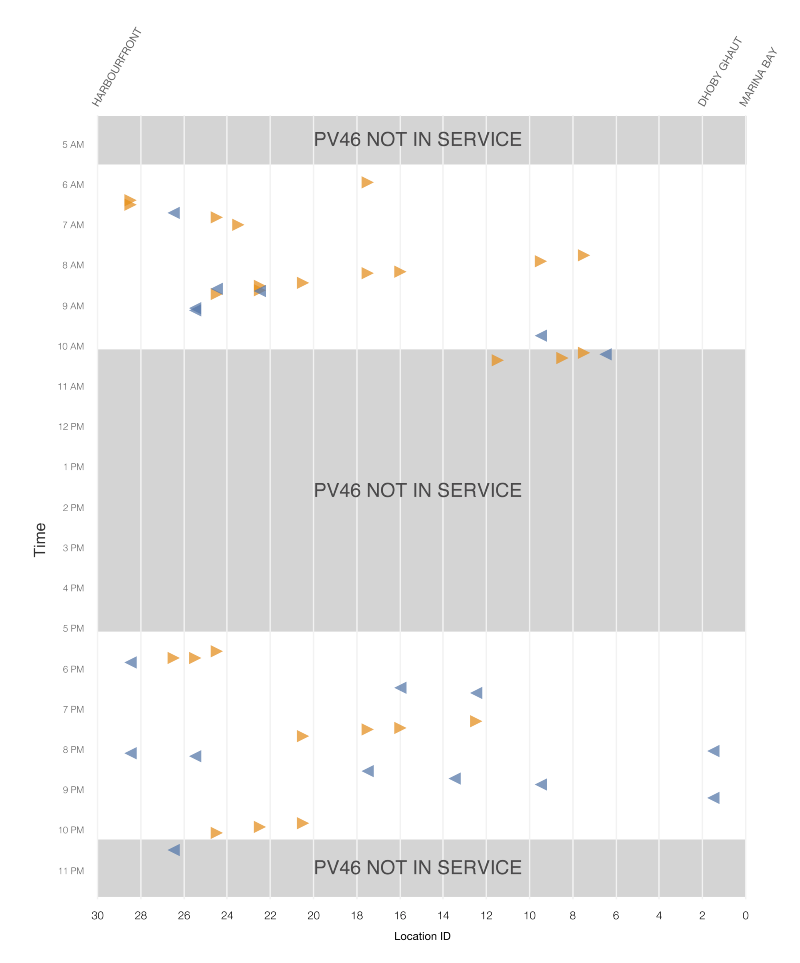

They even established that the incidents only happened when PV46 was in service:

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Screenshot from data.gov.sg

Although the credit was given pretty much completely to the DSTA engineers, it was actually these three guys who did the legwork and accurately pinpointed the exact train that was causing all the trouble.

And we're glad that the Prime Minister has recognised their work.

So here's a salute from us to you, Sim, Ng and Lee. You have done Singapore, and the thousands of commuters who take the Circle Line every day, a great public service.

Top image: Screenshot from YouTube

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.