Singapore on steroids.

This was what Brexit campaigners were selling before the European Union (EU) referendum in the United Kingdom last Thursday.

It was also mentioned twice last week in the influential news weekly The Economist (see an example below).

Source: The Economist

Source: The Economist

So, our nationalistic nation-building newspaper decided to take a step further by commissioning a contributor to draw some similarities between Brexit and Singapore after its separation.

Before Charles Tan Meah Yang proceeded with his thesis ("Brexit: Why I voted Leave - A Singaporean in UK"), the Commonwealth citizen rubbed salt in the British's wounds by saying that he was shocked that UK had voted to leave the EU — note that this was even though he himself voted for Leave.

In fact, he asked this rhetorical question — "why would I vote for Leave when, arguably, I have benefited most from EU membership?"

Because he believed.

"I was swayed by Leave's uplifting message of optimism that despite the risks and uncertainty, Britain was better off being the master of its own destiny, unshackled from an EU that lacked democratic legitimacy. It was, in some ways, almost a triumph of hope over fear."

And had faith.

"Rather, while there was no doubt that Brexit would be detrimental (particularly to Londoners) in the short term, I had faith in the resourcefulness of the British people to identify and iron out any issues in the long run."

This is when things get a bit complicated — Tan attempted drawing parallels between the Britain-EU relationship and that of Singapore and Malaysia prior to separation.

And the two commonalities he pointed out?

a) a lack of common culture, and b) a bureaucracy of a larger economic entity that is stifling business and innovation of the smaller territory.

In other words, you can use these two observations on almost any distinction between a country and a more developed city/region: UK-London, US-California or even Singapore-Raffles Place.

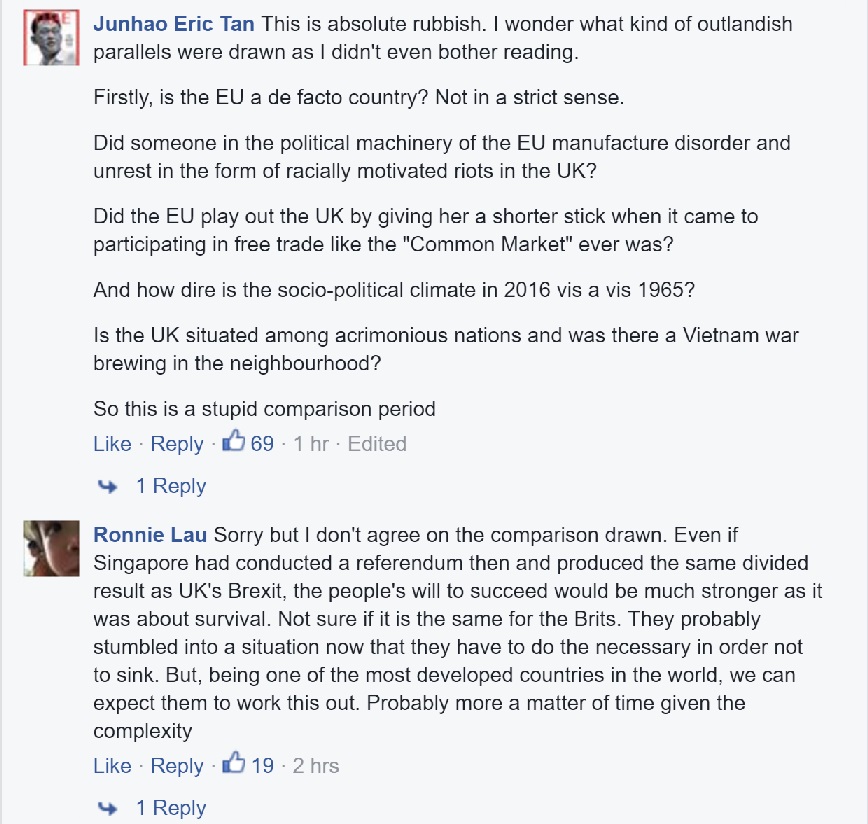

Here are two of the most popular comments to the post on The Straits Times's Facebook page.

Source: ST comment

Source: ST comment

Now let's hear what public intellectual and local economist Donald Low has to say about it —

In brief, Low said, "No, kids, Brexit is NOT like our Separation in any way." He also gave four good reasons why, which we break down here:

1) Malaysian Federation ≠ European Union.

It seems this actually needs to be said. Beyond the blindingly obvious facts of size and importance, Low notes that Singapore joined Malaya for a Common Market — free movement of goods and services between us and the rest of Malaysia.

Sadly, that didn't happen when we merged; not only that, we also lost control of foreign policy and defence — and hence our state sovereignty.

Britain, on the other hand, enjoyed sovereignty (foreign and security policies), their own currency AND free access to the world's largest common market, Low says.

Look, even the Brexit leaders are trying to protect Britain's ability to move their goods and services into Europe now — but sorry, fact is you can't have your cake and eat it too.

2) Singapore did not succeed IN SPITE of Separation; rather, it succeeded BECAUSE of it.

If you say it was a bad idea to merge with Malaya, it follows that you agree it was a good thing for us to leave them, says Low.

In fact, it was our departure from Malaysia that allowed us to explore our own economic strategy of export-led industrialisation, which Low calls "history's surest path to prosperity".

Turning to Britain, even if you think they could pull of what we did — they need to re-negotiate access to the rest of Europe and other markets, which it initially already had with the EU. And even if it does regain control of immigration, good luck trying to convince foreign investors that they're a free-trading, talent-welcoming and multicultural society.

3) Singapore's reasons for leaving ≠ Britain's reasons for leaving.

Let's talk about race, then. Low argues Singapore left Malaysia because of rising racial tensions, intolerance and race-based politics, and leaving allowed us to build a culture of meritocracy and multiracialism — imperfect as it is.

Britain voted to exit the EU because, at least in part, of racism and intolerance to foreigners in their midst.

4) Saying all Britain needs is a leader like the late Lee Kuan Yew is trivialising his and our first-generation leadership's achievements.

The late founding prime minister, Low argues, was crucial to Singapore's success immediately after separation, because of his humility in admitting that an idea he was really committed to and invested in (merger) turned out to be quite a bad one.

Besides, was it just the late Lee who brought Singapore to where we are today? Hardly — just saying "we had LKY, you have Boris Johnson" downplays the role of Lee's first-generation leadership team, and also all the Singaporeans — our pioneers and even our baby boomers — who worked real hard and got us here.

Low also couldn't resist a dig at ex-PAP member and ex-NMP Calvin Cheng, who also touched on this comparison:

Importantly, though, Low points out that instincts of elitism, intolerance and racism are present in all of us — hence the importance of education and history, which both teach us to suppress these instincts and be better people in our relationships with others, and, it would follow, build a better society.

Here's the full text of Low's Facebook post here for your convenience:

The people drawing parallels between Britain leaving Europe and Singapore leaving Malaysia in 1965 - with the implication that Britain could succeed post-Brexit in the same way Singapore succeeded post-Separation (if only Britain finds a leader like LKY) - are completely wrong. It's a view that's NOT even somewhat accurate or half-right but provides useful historical parallels and lessons. It's just completely inaccurate. The people who spout this view (and it's not just Calvin Cheng) know nothing about Singapore's economic history, how federalism works, and Britain's relationship with the European Union.

This view, which is somewhat seductive and instinctively appealing, is completely wrong for at least four reasons.

The first and most obvious is that the Malaysian federation was nothing like the European Union - and I don't just mean this in terms of their relative size and importance. Singapore joined Malaysia believing that it would have access to a Common Market, i.e. free movement of goods and services between Singapore and the rest of Malaysia. This didn't happen. Meanwhile, it didn't have control over the key institutions of state sovereignty - foreign policy and defence. In short, when Singapore was part of Malaysia, we had all the costs of being part of a federation (loss of sovereignty, no independent economic policy), but none of its benefits. Singapore being a part of Malaysia was simply a lousy idea.

Britain's case is completely different. Being part of the EU gives it access to the world's largest common market. Joining the EU, unlike Singapore joining Malaysia in 1963, was a very good idea. It still is. It is very telling that even the Brexit campaign leaders want to safeguard the entry of British good and services into Europe. But they also want to limit the free movement of people from the rest of Europe into Britain. Unfortunately, you can't have your cake and eat it too. So in the case of Britain, unlike Singapore when it was part of Malaysia, it has all the benefits of European federalism, albeit with some attendant costs (the main one being the loss of control over immigration). Britain also has its own currency (i.e. it hasn't given up monetary sovereignty), and pursues it own foreign and security policy.

Second, the view is wrong because it suggests that Singapore succeeded in spite of Separation. If you agree with the first argument - that joining the Malaysian federation was a bad idea - then you'd also agree that Singapore leaving Malaysia was a blessing. Albert Winsemius, one of the architects of Singapore's industrialisation, certainly believed so. He thought that the two years that Singapore spent in Malaysia were two years wasted insofar as industrial development here was concerned. Specifically, leaving Malaysia meant that we were free to pursue the economic strategy that turned out to be history's surest path to prosperity: export-led industrialisation.

Can Britain do the same? Perhaps, but it would have to negotiate access to Europe and other markets - something it already has as part of the EU. Meanwhile, regaining control of immigration is a Pyrrhic victory if, as a result of Brexit, Britain loses its reputation as a free-trading, talent-welcoming and multicultural society.

Third, the political-philosophic basis of Singapore's leaving the Malaysian Federation was entirely different from why more than half the British people who voted in the referendum want to leave the EU. For Singapore, continuing to be part of Malaysia would have meant an increase in racial tensions, intolerance, bigotry and divisive, race-based politics. By leaving Malaysia, Singapore was able to carve out a space for itself to pursue multi-racialism and meritocracy. The contrast with Brexit cannot be any greater. The people who voted to leave Europe are motivated, at least partly, by a latent racism and aversion to foreigners.

Fourth, the view is wrong because it misrepresents the nature of leadership. It suggests that all the British people need to do to create a prosperous, dynamic Britain after Brexit is to find a messianic leader - someone like LKY. This view is completely ludicrous. People like Calvin Cheng think they are paying a tribute to LKY when they say cute things like "we had LKY; you have Boris Johnson." In reality, they are trivialising LKY and Singapore's achievements.

LKY was crucial to Singapore's success in the immediate aftermath of Separation. Perhaps his most important contribution was that he was honest, humble and courageous in admitting that he was wrong about Singapore being a part of Malaysia. Leaders and decision-makers often suffer from something known as the "sunk cost fallacy", the common mistake of throwing good money after bad, of increasing our investments (of money, time, effort) in bad ideas on which we had staked our reputations. Mr Lee didn't suffer from this. He abandoned the bad idea (Singapore as part of Malaysia) after less than two years even though he was personally very invested in that idea.

Finally, there's a great irony in someone like Calvin Cheng rubbishing Boris Johnson. The fact of the matter is that the two of them are fundamentally alike - they hate liberals, they pride themselves as conservatives, they appeal our respective countries' sense of exceptionalism. Boris Johnson (very much like Trump in relation to the American people) reflects the worst instincts of the British people - elitism, insularity, parochialism, intolerance. And in winning the referendum, he has legitimised those instincts - as evidenced by the increasing incidence of racist incidents in Britain. Calvin Cheng appeals to those very same instincts. We all have those instincts. Part of the purpose of education, and of history in particular, is so that we learn to suppress those instincts and let our better selves govern our relationships with others. This is why his misrepresentation of history is not just wrong and misguided, but also disingenuous and dangerous.

Still think Separation is like Brexit / Britain is Singapore on steroids?

Top photo via NLB

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.