Firsthand Takes On: Housing is a new series by Mothership, diving into the topic of housing in Singapore with in-depth articles and videos.

We’ll explore the uniquely Singaporean housing system by experiencing it for ourselves, gathering expert opinions, and hearing the perspectives of young Singaporeans, to present the points of view that matter, firsthand.

Since 2021, Charlotte (not her real name) has been renting an apartment with her husband, Darren.

Such a situation might have been unusual in the past, but no longer. The young Singaporean couple is just one of many who were hit by Build-to-Order (BTO) flat delays in the wake of the pandemic.

They initially managed to get a studio apartment in Geylang for S$1,950 a month. But nearing the end of their lease, they were informed that the price would be increased to S$2,400: a change that the couple, who are both teachers, couldn’t afford.

In hopes of getting a cheaper place to stay, they applied for the Parenthood Provisional Housing Scheme (PPHS) — a rental programme launched in 2013 to temporarily house families while awaiting the completion of their flat — but were unable to get a suitable flat.

Left without alternatives, the couple decided to move back in with Charlotte’s parents.

“It’s quite sian because we’re stuck in a room, with no private space. We don’t even watch TV now,” she says wryly.

“Living in limbo” — as Charlotte puts it — has also affected their family planning. “We have not given serious thought about kids, probably also because of the lack of stability,” she tells me. Both are in their early thirties.

“I think as a couple it’s important to have our own space. [Without one], you have no private space, not even to quarrel. You’ve no place for rest cos it’s not your own…even when you’re sian, you still got to pretend to be okay in front of your parents.”

Not just a foreigner’s problem

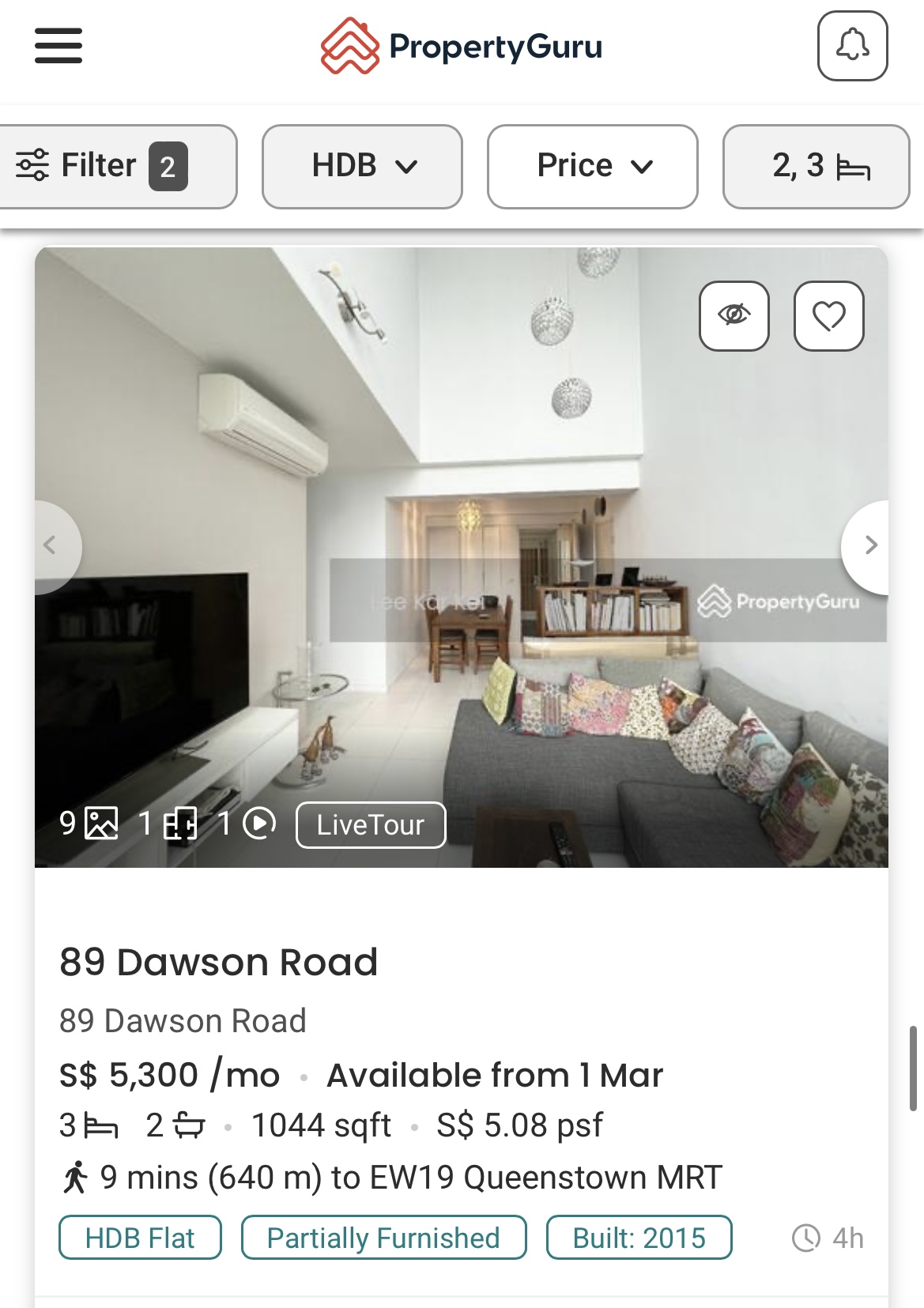

Rental figures have skyrocketed, with a quick search on PropertyGuru showing figures well beyond the means of the typical Singaporean (from S$3,000 for a partially-furnished, three-room HDB flat at Petir Road, to over S$5,000 for a four-room loft unit at the centrally-located Skyterrace@Dawson estate).

The increase in HDB rents — which amounted to a staggering 27.8 per cent in 2022, according to a Straits Times report — wouldn’t have been of particular interest to most locals a decade or so ago.

After all, Singaporeans have always been meant to own their homes, rather than rent; the latter was seen largely as a “foreigner’s problem”.

But times have changed. And Charlotte isn’t alone.

It’s difficult to get the exact numbers, but the evidence seems to point to a trend that Singaporeans are renting more.

For a myriad of reasons. A recent study by PropertyGuru showed that more young locals are considering renting, largely due to high property prices and inadequate savings.

Another factor driving demand in the rental market is singles’ desire for personal space. With more in each generation marrying later (or not at all), there are more singles outgrowing their parents’ homes and turning to renting.

Most significant, however, was the Covid-19 pandemic. Manpower shortages drove construction projects to a halt, causing building delays, and driving stranded couples to rent — something they might have once scoffed at as uneconomical.

Work-from-home and Zoom meetings have also become a mainstay in local corporate culture, resulting in a renewed sense of urgency for personal space.

Property agents Mothership spoke to observed that locals, particularly young singles and couples, have indeed been renting more.

And according to Wendy Yap of CP Residences, a co-living and accommodation services provider which manages approximately 150 properties in Singapore, the occupancy rate of local tenants in its apartments has increased from 1.76 per cent in 2014 to around 25-30 per cent in 2022.

However, data from the Ministry of National Development (MND) shows that over the past 10 years, locals comprise just 5 to 8 per cent of HDB tenants. In response to a request for a breakdown, an HDB spokesperson said:

"The proportion of Singaporean tenants renting HDB flats from the open market has remained low, averaging around 5 per cent for the past 5 years (i.e. 2018 to 2022)."

It's apt to note that this data includes only whole-flat rentals, which means locals who rent master or common bedrooms are excluded from this number. "Some Singaporean households may be renting as they await the completion of their homes," the spokesperson acknowledged.

Still, growing demand means growing prices. Going by the common rule of thumb, which dictates no more than 30 to 40 per cent of an individual’s paycheck spent on rent — S$3,000, while attainable on an expatriate’s salary, may be less feasible for a pair of young Singaporean newlyweds.

And in some cases, impossible.

Searching for a foothold

The rent problem hasn’t gone unnoticed by the authorities.

Member of Parliament Louis Ng has called for more rental aid to be extended to singles, particularly those among the lower-income stratum. Separately, a number of policies have been installed to staunch the bleeding, like the PPHS.

But they have floundered under the relentless impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The PPHS, initially intended for young parents, has since become a desperate foothold for the recently-married.

Young couples like Charlotte and Darren, lacking the means to rent on the open market (the PPHS has an income cap of S$7,000, with no priority for those with lower income within that ceiling) have turned to the scheme in droves to tide through their BTO delays.

As a result, application rates have soared, slimming the odds of getting a flat. In August last year, MND said that there were nine times more PPHS applicants than units available — rivalling that of a well-situated BTO launch.

Meanwhile, other young couples, unable to bite the bullet of increasingly out-of-reach rent, have been left scrambling for alternative solutions to the challenges they might face to family planning, privacy, and the simple logistics of having enough space.

Some end up living separately in their parents’ houses while waiting out their BTO delays, or turning to relatives or friends with spare units for help.

Another couple, who was told that their rent would be increased by 75 per cent upon the expiration of their lease, plans to move in with the man’s in-laws temporarily — something the woman, 28-year-old Ophelia, feels very paiseh about. “But no choice lah,” she says, adding that they will search for a resale flat in the meantime.

“An extra S$1,500 a month is definitely not feasible for us,” Ophelia explains. “We were expecting the rent to go up for sure, but didn’t expect it to go up THIS much.”

While she does not blame her landlady for increasing prices, calling the separation “civil”, this experience has left Ophelia with a bitter taste in her mouth.

“I hope I never have to rent a house again,” she tells me.

Market pressures

But just how bad is the situation, really?

In the words of property agent Shaik Amar, who goes by the moniker @thatproperty.guy on TikTok — “it’s really ridiculous,” he says. “It’s mad.”

Across the board, HDBs and private properties alike have suffered astronomical increases in rent. He points out one example — a four-bedder condo unit in Eunos that was rented out for S$8,000 a month — and another that went for S$10,000.

“It’s insane!” Shaik exclaims. “In 2019, you could rent a landed at the same price, for your understanding of how horrible the rent is right now.”

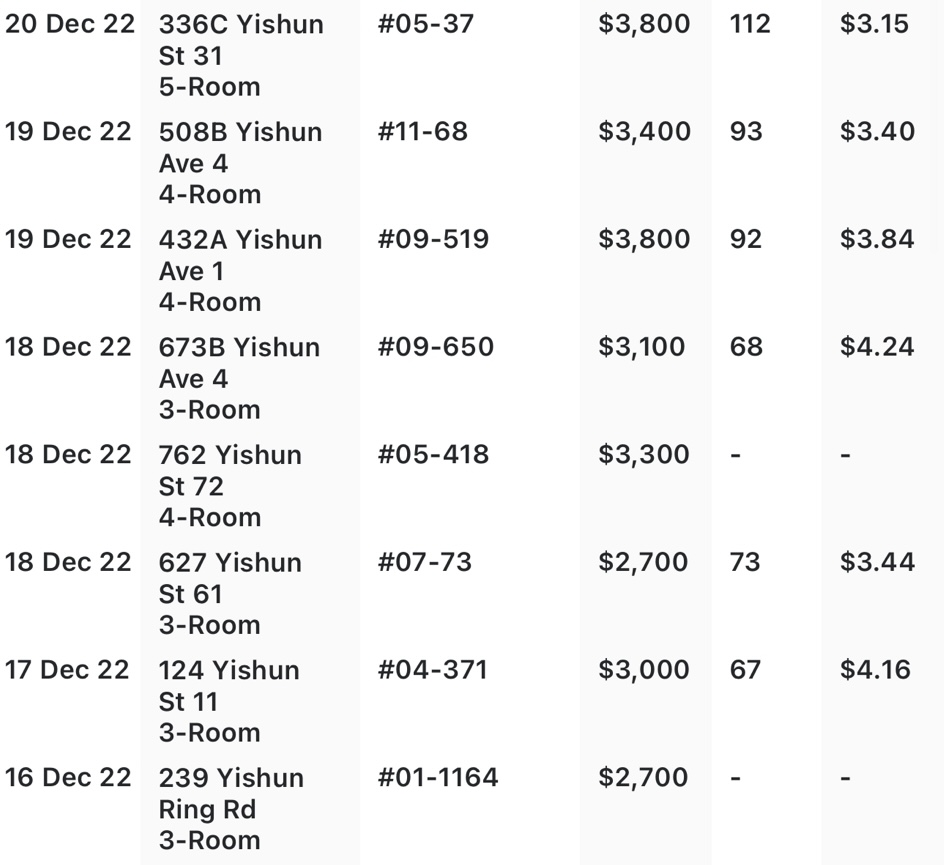

Data from property and real estate portal SRX on HDB flat rental rates is equally alarming. Between Dec. 15 and 20 last year, three- and four-room units at Yishun St 81 went for between S$2,200 and S$3,800.

In contrast, median figures for rent across the year, as reported by the Ministry of National Development, pegged units in non-mature estates as going at between S$1,700 to S$2,600.

With such dizzyingly high prices, even those already renting are facing pressure from landlords enticed by a barrage of willing enquirers, offering to pay market rate.

One TikTok user, who goes by the username @salshoult, recently posted a video venting her frustrations about her landlord, who had allegedly raised her rent by 75 per cent.

“And I’m reliably informed that it’s an excellent deal because if we choose not to accept, he’s going to put it onto the market at a 100 per cent increased rate,” she exclaims.

“So yeah, I’m moving out.”

A correction in the future

The developments in the rental market are certainly unprecedented, and perhaps a touch demoralising.

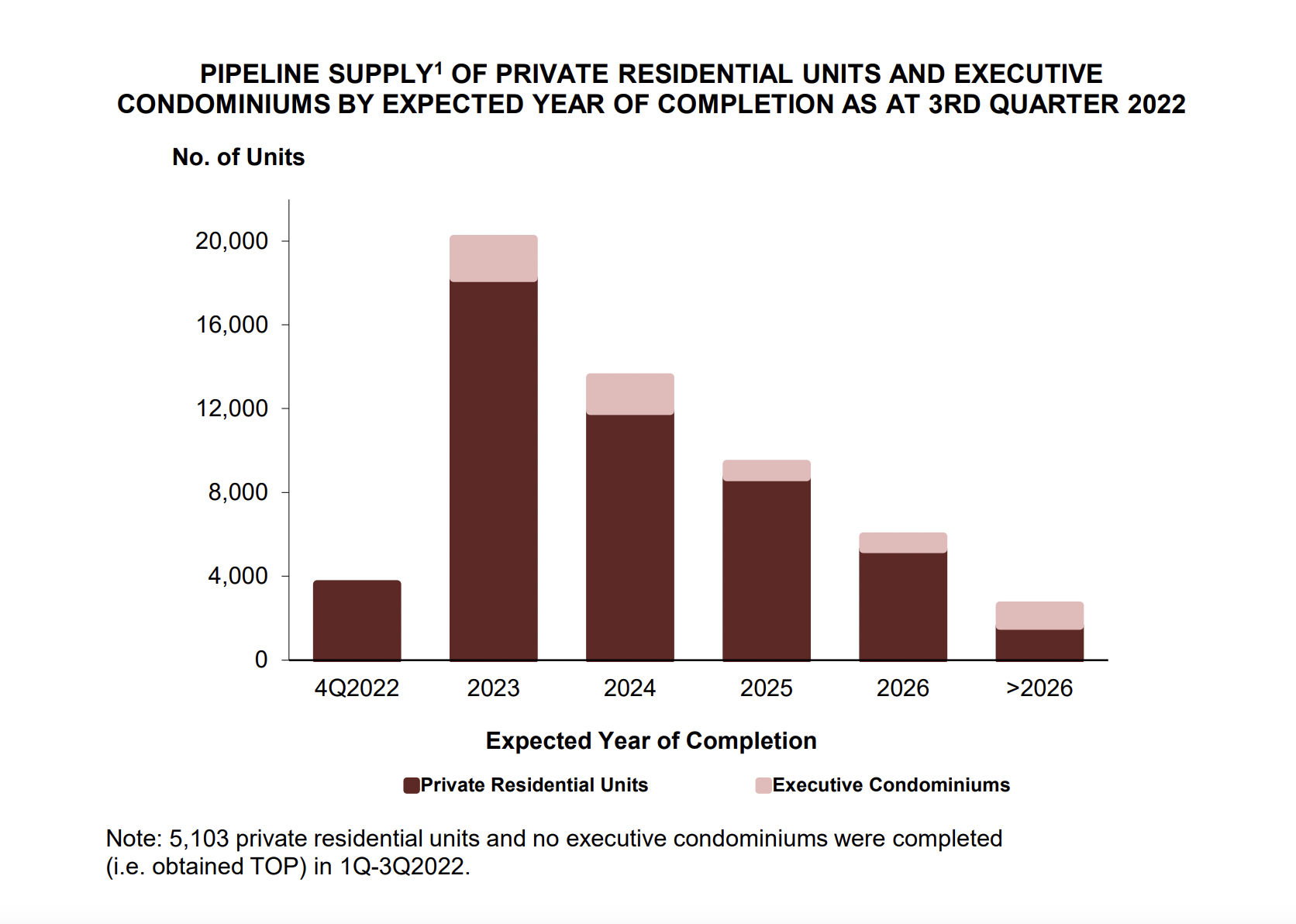

But Shaik is optimistic about the future. Moving into a post-pandemic world, BTO delays are likely to become the exception rather than the norm. The same goes for private property developments.

Singapore Management University Economics professor Eric Fesselmeyer agrees. “So my view is that [rental rates] are higher than they have been historically, I think they’re the highest they’ve ever been right now. And that’s probably not sustainable.”

His prediction: high prices will attract more people to rent out their flats, increasing supply. Between that and the government’s efforts to build more flats — “we’ll find some equilibrium,” Fesselmeyer says, “[and] I think rents will probably come down.”

The caveat is that rent, when it does reduce, does so extremely slowly.

This is because people sign leases, Fesselmeyer explains. “So when you sign on a two-year lease, and rent starts coming down — you’re not going to have any kind of relief for at least a couple years.”

Still, Shaik expects the relief to kick in as soon as in a matter of months. “Where I see it, from June, we should start to see a decent correction of about 10 per cent in the rental market,” he tells me.

"And a slow, gradual decline, as more and more supply starts to enter the market.”

Meanwhile, Minister for National Development Desmond Lee announced late last year that the government would double the supply of PPHS units to 1,800 in 2023.

Combined, these measures may culminate in some relief for the overheated rental market.

Reevaluating the future of rent

But the damage has been done. The rental market can spiral out of control, as it did in the past few months.

It’s apt to consider, then: should renting, from a policy point of view, be expanded to include the needs of locals?

Population data has given us a glimpse of the future. Marriages today are an event of the late-twenties at best, or thirties at likeliest. This could drive more couples to rent as a temporary solution once they do decide to get married.

At the same time, more people than ever are choosing to remain single. Despite the government’s gradual relaxation of housing policies directed at singles, the 35-year minimum age for the purchase of a flat remains firmly in place.

As such, this group, too, has and is likely to increasingly turn to renting, Shaik believes.

Such lifestyle changes mean that the upward pressure on rental rates is unlikely to subside anytime soon.

Furthermore, we’ve come to be familiar with the “template” Singapore couple who plan their wedding timelines around the estimated completion of their BTO.

Renting — for a period of time, while awaiting their new home’s completion, or while saving up for a home of their own — could well become a part of the template too.

Rent could also be a lifeline for those who with nowhere else to go.

Lynn (not her real name) began renting a room in an HDB flat two years ago. Despite the prohibitive costs of renting, long-standing conflict with her parents — some of it physical — pushed her to go her own way.

“It was a very unstable environment to grow up in,” she explains, “so I resolved to move out rather early on.”

At 25, she hopes to save up for a flat, but it “feels like light years away”; rent alone takes up 25 per cent of her income.

Meanwhile, as she continues to rent, she fears that it will become even less affordable. “People move out for various reasons, and many times out of necessity,” she says.

Some government oversight on rental costs, especially for HDB flats — which are meant for public housing — might be apt, Lynn says.

This can help provide some peace of mind for those who rent, she adds, highlighting the fact that in situations like hers, a rented space is a necessity.

Should rent be protected?

Protecting the rent prices of public housing may seem a touch radical — but it wouldn’t be unprecedented.

Government-led initiatives, like price caps and ceilings, have historically been used in times of economic uncertainty to protect resources deemed public necessities.

Last year, Malaysia fixed a statutory price ceiling for chicken amid plummeting prices. Australia passed a law introducing domestic price caps on coal and gas. Amid rapidly rising rent costs, Scotland passed emergency legislation freezing rent for six months.

Even here in Singapore, the government announced two consecutive rounds of property cooling measures targeting soaring HDB prices, barely a year apart.

As it is, the authorities are taking a cautious approach towards rent. In October 2022, Lee said that the government is currently not considering plans to introduce rental grants.

“Providing direct subsidies or grants for renting flats from the open market will likely induce demand and may drive up market rentals, which would be counter-productive as it makes renting more expensive,” he said, suggesting that families instead consider alternatives, such as staying with family members.

He added that low-income families may be offered Interim Renting Housing — a scheme that provides temporary housing for families with no other options — on a case-by-case basis.

Lee reiterated the government’s stance in the Committee of Supply 2023, in response to a query on the possibility of distributing rental vouchers for couples waiting for their flats.

The end of Covid-19 delays and increased supply of flats would likely help temper the rent market, he said.

It’s also notable that Lee didn’t rule out the possibility of government intervention, saying:

“We’ll certainly keep an open mind, and keep a close eye on the situation, and we’ll be prepared to take necessary measures in order to support Singaporeans.”

But with rent quickly becoming a problem for both expatriates and Singaporeans alike, what would it look like if measures were taken to protect the HDB rent market?

Rent control could help prices in the short-term. But what often happens is landlords stop maintaining their properties, attempting to push out tenants or compensate for their lower earnings — especially in the light of rising interest rates.

Furthermore, “there’s two sides to every story,” Fesselmeyer points out. “For every person that enjoys lower rent, there’s some landlord that’s now getting lower rent as well.”

“So it’s not clear. If you wanna favour people that need to rent an apartment or flat, then yeah, of course rent control will help. But it also hurts people.”

High resale prices and demand are also partially responsible for driving individuals to rent.

As such, further cooling measures might offer some relief — but Fesselmeyer says the government has traditionally avoided being too heavy-handed in the property market.

As such, while the government continues to ramp up the supply of new flats, what might be best would be for renters “to grin and bear it,” Fesselmeyer concludes.

Falling through the cracks

What happens if someone just can’t afford rent, does not qualify for HDB’s rental schemes, and has nowhere else to go?

This was a question I posed to Shaik towards the end of our interview, one that had been nagging at me for a while.

He shrugs. He doesn’t know. Some have it harder than others — a number of his Indian clients, for example, have to contend not just with the prices, but also pickier landlords who now have plenty of prospective tenants to choose from.

It’s gotten to the point that with some clients, he just says sorry, I can’t help you.

Most get by somehow. Humans are adaptable. One family ended up renting two common rooms, he recalls.

“So technically, they are living together,” he says wryly. “I mean, that’s the best they can do, right? Your privacy is completely affected…you can’t live your life. But it’s really a place to sleep, and then go to work.”

But others fall through the cracks. “You hear some stories. Students, especially,” he tells me. “They come to Singapore, they go to [university], and then all of the hostels are already full. They have to go out and rent.

“But what happens if your parents are not rich? Then how? You didn’t know this before [you came into the country].

It’s sad. It’s really sad…a bit heartbreaking, sometimes.”

Top image adapted from photo by Joyce Romero on Unsplash

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.