Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

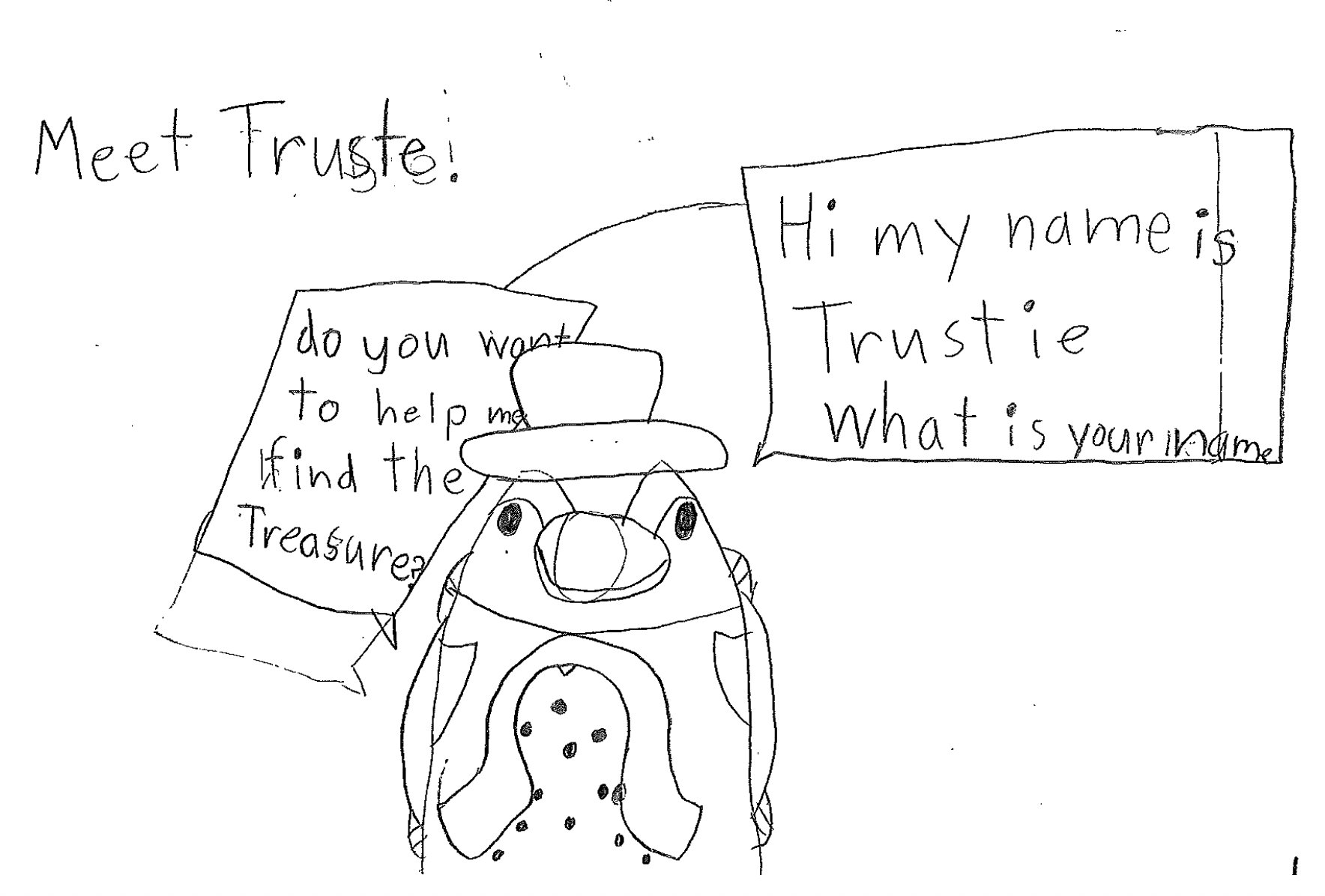

Once upon a time, as the story goes, there lived a penguin called Trustie.

Trustie is an African penguin. He has a few distinctive features: a hint of pastel-pink in his lower beak, a scattering of spots at his abdomen.

Trustie's kind of the adventurous sort. In the story, he goes on adventures with his friends — an elephant and a giraffe among them — to uncover a hidden treasure. He crosses rivers, climbs mountains, and traverses caves.

But this article isn't about Trustie, not really. It's about his creator: a soon-to-be Primary Two student named Darren.

Darren likes animals, LEGO, and reading about STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) topics. His favourite snack is ang ku kueh and his hobbies are drawing and playing games.

Bright and inquisitive, he seems like a perfectly ordinary, perfectly healthy child.

But he hadn't always been: Darren was three years old when he was diagnosed with Wilms' Tumour, a rare kidney cancer that affects children.

It was during this battle with cancer that he created Trustie.

Making a story

Darren has loved to draw for as long as he can remember, and maybe before that.

At the interview, he shows me his various muses: a pink penguin plushie called Queek Queek (based on his mother, Iris Tan); a blue penguin called Baby Queek Queek ("because I wasn't that creative, I couldn't think of anything," explaining how he named it); and the latest addition to his collection, Trustie — the book character's namesake.

"Because I was creative now," he informs me. "I was very artistic."

Drawing was his solace during his long periods of hospitalisation. Barely a week after being diagnosed, he was whisked away to the operating theatre where his left kidney was swiftly removed. Subsequently, he went through four and a half months of painful chemotherapy.

It was a terrible time, Tan tells me. The drugs made his hair fall out and subjected him to relentless nausea. "When he ate, he would vomit," she explains. "People have 'sleep-walking'. But Darren was 'sleep-puking'."

"Because his body is so tired, he slept. But his body cannot keep the food in his stomach, so he has to vomit it out."

"But he's so tired, he cannot wake up. So he was sleeping and puking at the same time...I clean him up, change him, and he still didn't wake up. Because he was so tired."

It was then when his oncologist referred him to Make-A-Wish. "At that time, I thought Make-A-Wish is for those terminally ill children," Tan admits. "So I had the perception, 'huh, why are you granting Darren a wish?'"

"But then he told me that Make-A-Wish is for any child who has critical illness, not exactly terminally ill. Then I said, okay lah, if you want to make this happen for him."

Fortunately, the treatment worked, and Darren was soon well enough to have a wish granted. Unfortunately, Covid-19 struck, and so his initial wish — to go to the Natural History Museum in London to see its famous dinosaur exhibits — became impossible.

As a compromise, his volunteer wish-granters, 29-year-old Cheryl Ng and 58-year-old Suzanne Liu appealed to his second love: animals. They arranged a private tour of the Singapore Zoo, where Darren promptly fell in love with the African penguins.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

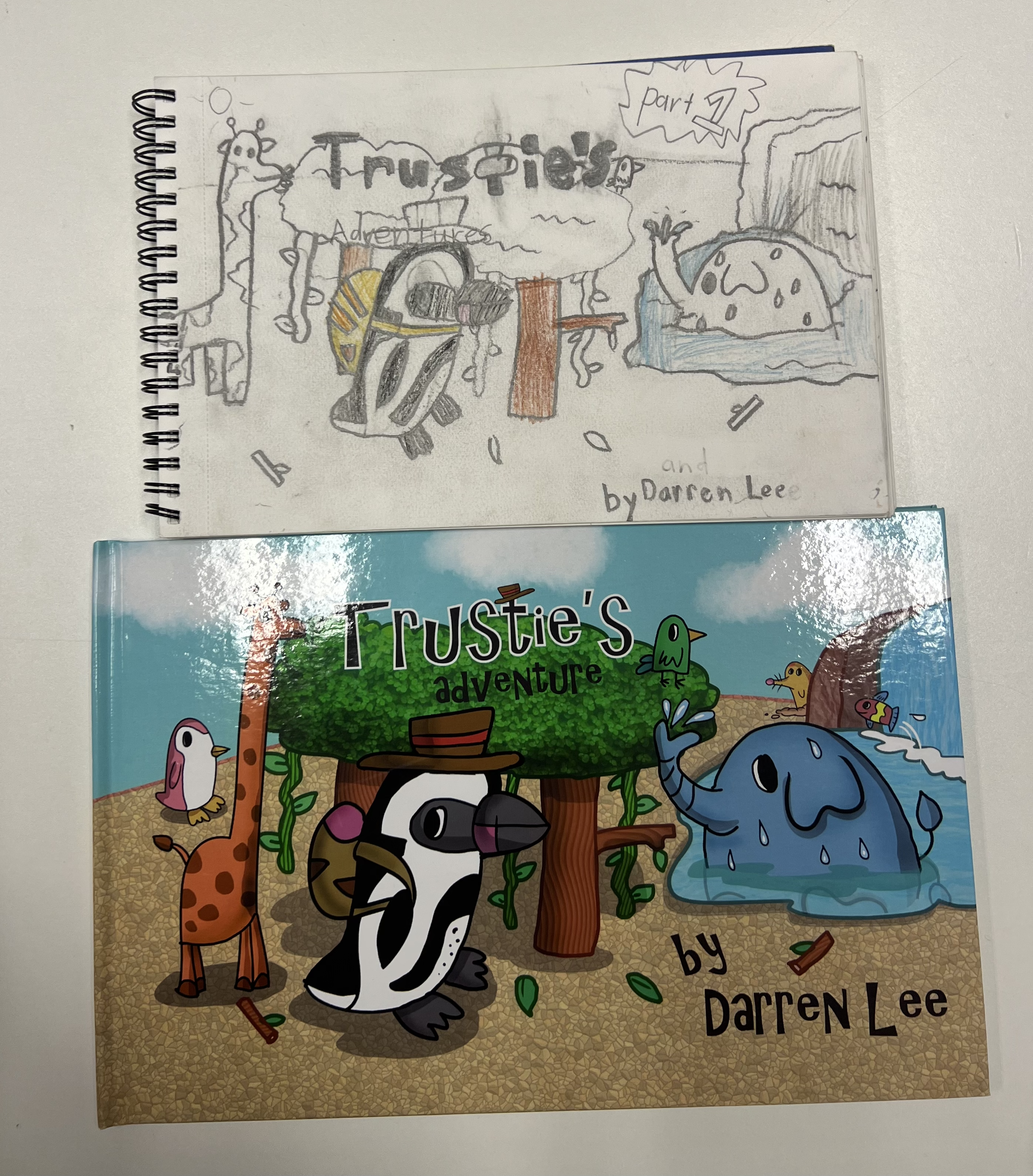

Aware of his love for drawing, Ng and Liu presented him with a sketchbook and colour pencils and told him to go crazy.

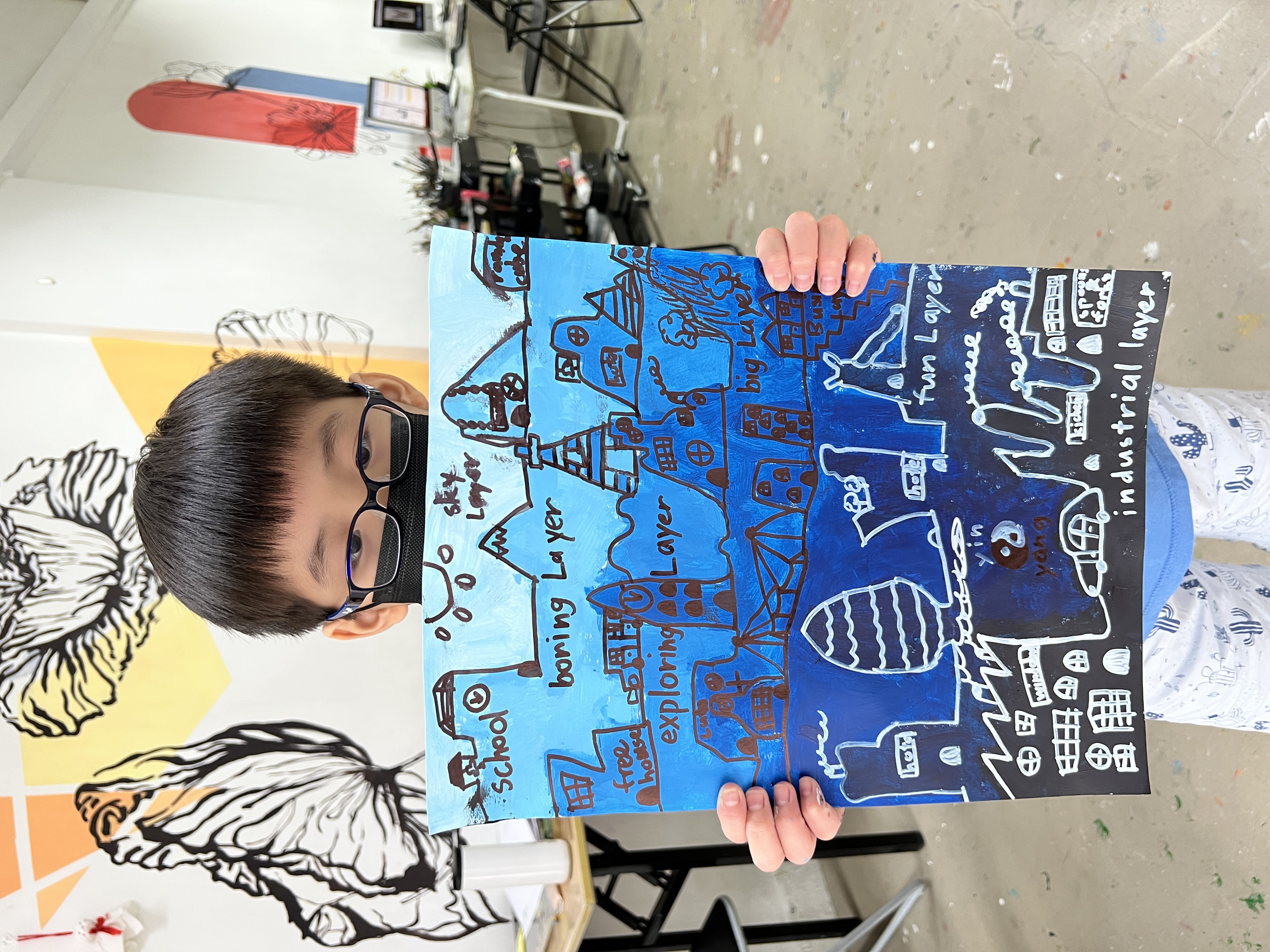

But instead of doing individual drawings, Darren began to create a story — Trustie's story.

"Finally, he finished after three months," Tan tells me. "And he said something like, 'Mummy, how nice it would be if other children can read my story.'"

"So I asked Cheryl and Suzanne if they can help."

Behind the scenes

And help they did. But despite what the organisation's name might suggest, the magic doesn't happen with a flick of a wand.

In the absence of a fairy godmother, months of hard work are dedicated to planning, coordination, and logistics. Real life gets in the way, too — finicky little things like physics and laws. In Darren's case, it was the pandemic; another child, Ng recalls, wished to parachute out of an airplane, but was unfortunately thwarted by his age.

To grant Darren's wish of sharing his story with the world, Auntie Suz and Cheryl Jiejie (as he calls them) set out to transform his sketches into a book.

The first step: to find an illustrator. They'd initially planned on getting someone to help out with the storyboarding, too, but Darren took to the task with vigour, even drawing out speech bubbles and titling each of the four chapters.

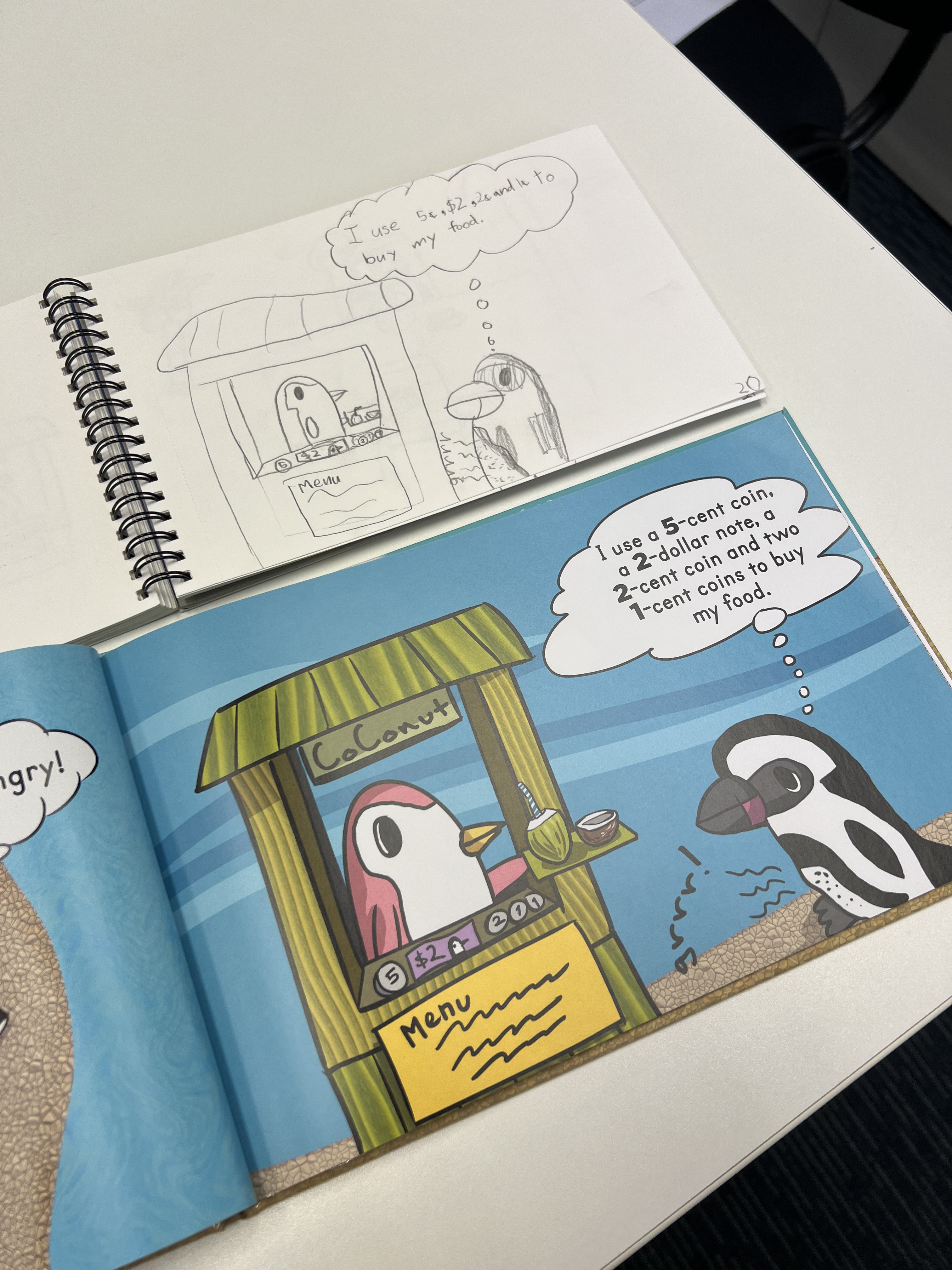

During the interview, when we go through the book together, he points out every single difference between his pencil sketches and the illustrator's digitalised version with the detailed eye of a critic.

He indicates one faded part of the original sketch, which was left out in the final version. "It was gonna be a shark, a shark chasing Trustie," he says. "But Mummy said, 'That's too violent'."

At another page, he indicates another difference. "Here, the stripes are more difficult, so I erased it," he explains. "Let the professional do it."

After the artwork had been approved by its young creative director, Ng and Liu had it printed and bound. In its initial run, they printed 50 hardcover copies and 200 softcover copies, which they distributed to friends and family.

(Darren hopes to eventually see it in libraries, too. But that's another story.)

Not the end of the story

Contrary to what you might think, Make-A-Wish is not about granting a child's dying wish.

The organisation aims to grant the one true wish of every child suffering from critical illness, and has been working toward that objective across 50 countries and four continents.

This, it hopes, will improve a child's quality of life and chances of recovery — and indeed, most of the wish children not only survive their illnesses, but also return to volunteer as a wish-granter in turn.

As such, the wishes are designed not to fulfil, but to transform.

In Darren's case, his wish was designed to encourage his growth as a budding artist and storyteller. But his wish-granters explain that even the simplest of wishes, like a room makeover or a new iPad, can be adapted from a simple gift into something truly meaningful.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

Photo courtesy of Make-A-Wish Singapore.

One young chef, for instance, wished for a new kitchen.

"And it sounds simple, right?" Ng quips. "You just move them out of the house for a few days, get the kitchen done, and move them back into the house.

"But I think you come back to the why of this wish, how to push [the wish] to become something that really stays with the child."

In this case, the team ensured that the kitchen was designed around her height (as she has a condition that makes her a bit shorter), and even sent her recipes for baking prior to the renovation.

"So before the kitchen gets renovated, she can already start practising her baking skills," Ng explains.

"Because ultimately the renovation is to enable her, right, to bake more and cook more for the family."

Sadly, not every wish has a happy ending. An inevitable part of being involved with critically ill children, death does occur — undoubtedly the hardest part of her work, says Liu, who was inspired to join Make-A-Wish because of her nephew, also a wish child.

But even in pain and grief, a wish can bring a moment of joy to a sick child or grieving parents.

One child, who was hospitalised his whole life, requested a room makeover. The team not only acquiesced, but even managed to obtain the doctor's permission to bring him home for just one night, where they held a party.

The team then printed the party photos into a book for his parents.

Liu recalls: "Even [during] his last few days, when I visited him in the hospital, they were going through photos with him."

"It gave him a bit of comfort, and you can still see a very slight smile despite all the tubes in," she says.

In another case, Liu shares, a girl passed away after her wish was granted.

Her father had never been very forthcoming. "Like, you know, very quiet. He's always like, 'oh, you can talk to my wife', and then excuse himself," she tells me.

"But during the wake...her father actually came and said, 'I'm so glad that it happened.' Because we brought so much joy to her."

Start of something new

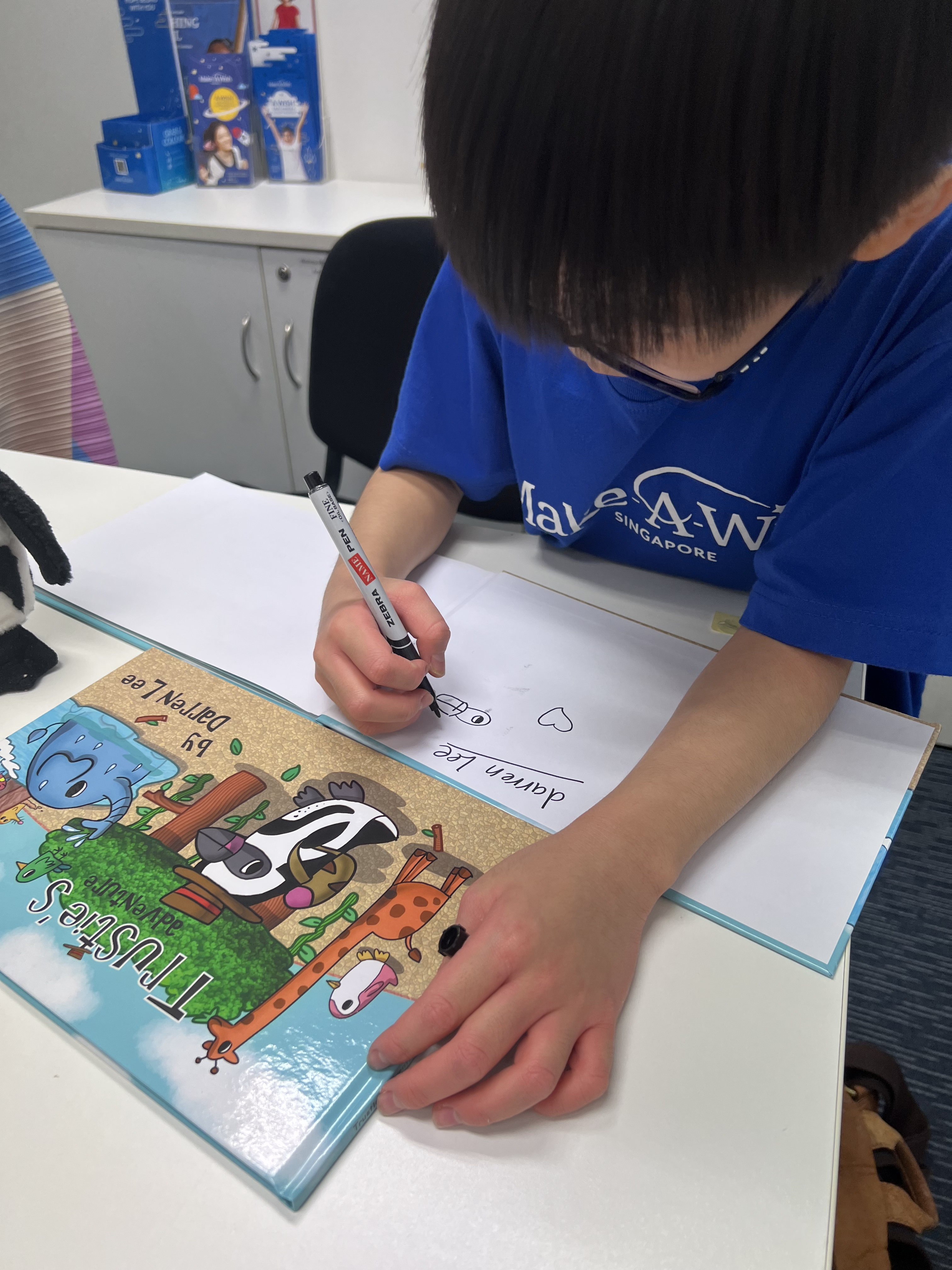

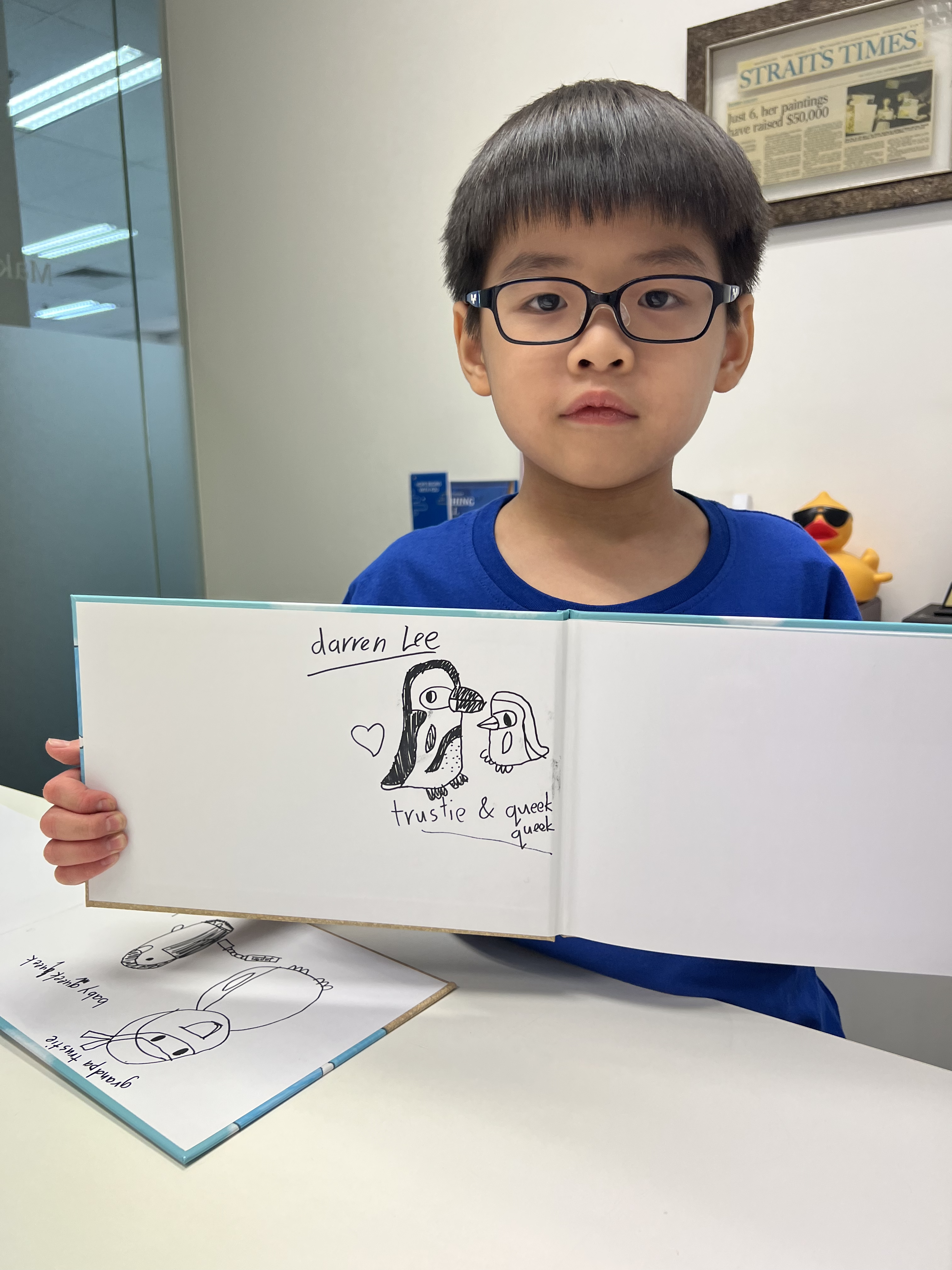

At the end of the interview, Darren presents me with a copy of his book. I ask him to sign it, and he obliges, even adding an off-the-cuff drawing of Trustie and Queek Queek.

As he draws, he offers me a sketch bearing a "sneak peek" of his next book. The sequel will feature two new characters, a capybara named Capy and a tortoise called Porpoise.

That's just the start of his new journey as an author. He aims to create one to two new stories a year, and foresees Trustie's adventures spanning a whopping 14 books. The series will conclude with an exciting twist at the end (which he whispered into my ear and I promised to keep secret), followed by an entirely new sequel series, featuring a new cast of characters.

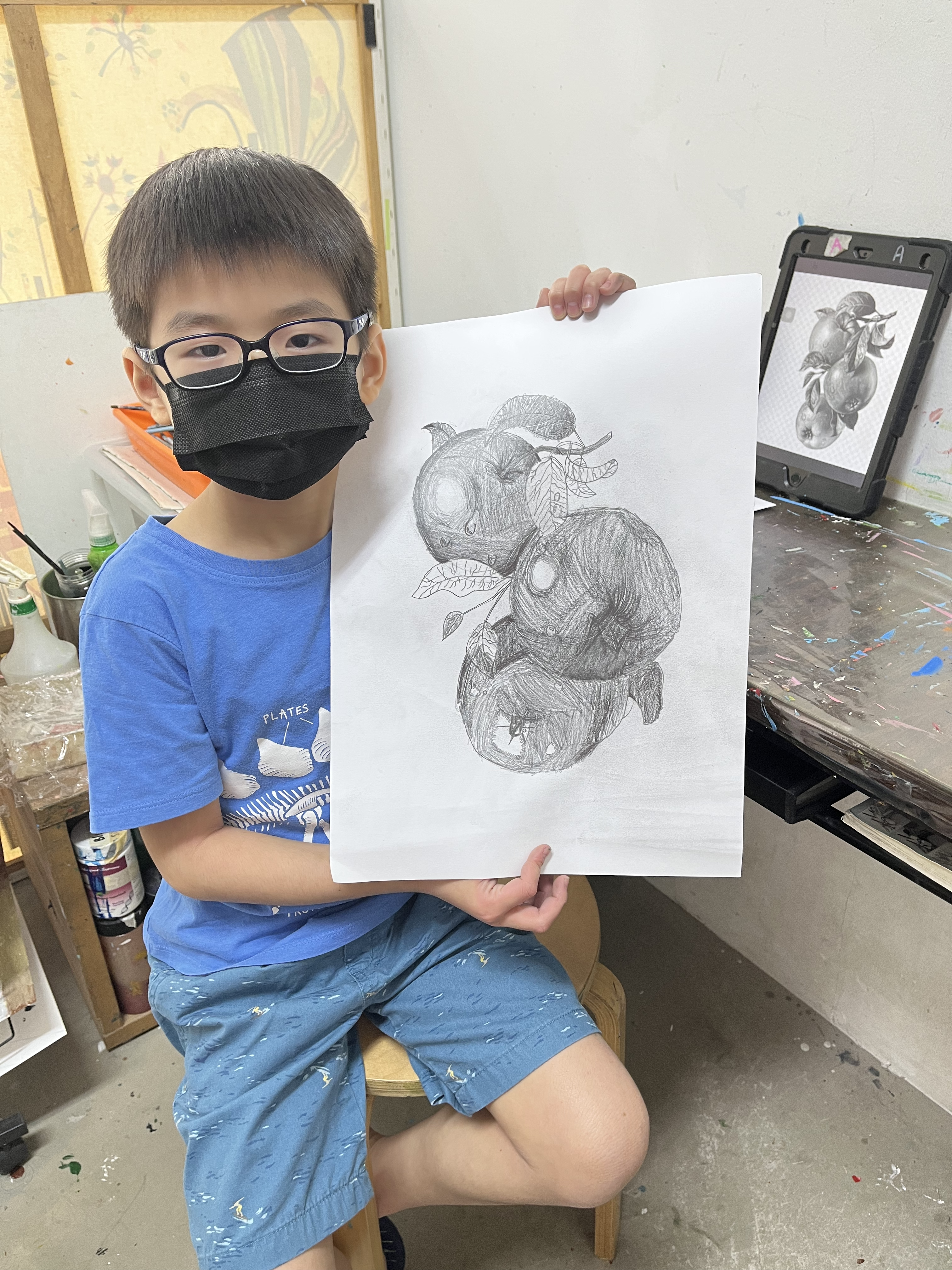

Outside of his budding career as an author, Darren has come a long way, too. He's now going for art classes, where he recently tried his hand at a still-life drawing.

Photo courtesy of Iris Tan.

Photo courtesy of Iris Tan.

Photo courtesy of Iris Tan.

Photo courtesy of Iris Tan.

When I ask him how his first year of primary school was, he tells me — with a somewhat uncanny maturity — that he still has much more to learn.

"There's so much more in the universe," he says. "How much I've learnt, is like how much we've seen to [sic] the ocean. We've only seen five per cent of the ocean. There's still 95 per cent of the ocean."

The not-quite eight-year-old tells me all these in a perfectly matter-of-fact tone, with the easy confidence of a child unhindered by fear of illness or failure. Success is inevitable; growth is necessary. All that lies ahead is possibility — an ocean's worth of it.

His mother is more cautious. While Darren is in remission, he still goes for regular check-ups; if the cancer recurs, the prognosis becomes much worse. And as Wilms' Tumour has no known cause, there's little they can do but watch and wait. "So that is like a lingering thing that we are both still very afraid of," she tells me.

Just a simple stomachache — his very first symptom from the initial diagnosis — is enough to turn her pale.

"If any other children, I will think maybe food poisoning, maybe stomach flu. But when Darren tells me his stomach is [causing him] pain, I think about the worst thing."

But for Darren himself, his days of cancer are a distant memory. He doesn't remember his chemotherapy experience — only a hazy understanding that he used to have a "poisonous stone" in his body.

Firsthand, his most recent encounter with pain was when his front teeth fell out a few months ago. His adult teeth haven't yet grown in, so when Tan tells him to smile for the camera, he does so with a hint of self-consciousness, his lips pressed tightly together.

Photo courtesy of Iris Tan.

Photo courtesy of Iris Tan.

Instinctively, I ask him whether it hurt. He considers the question carefully before answering. "Not that painful," he decides finally. "It was bleeding, and it felt like there was an ulcer there."

He thinks again, and nods. "Yeah," he repeats. "It wasn't that painful."

Top image via Make-A-Wish Foundation Singapore

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.