Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

It is the duty of the elected representatives of Parliament to deal with thorny social issues, rather than leave it to the courts.

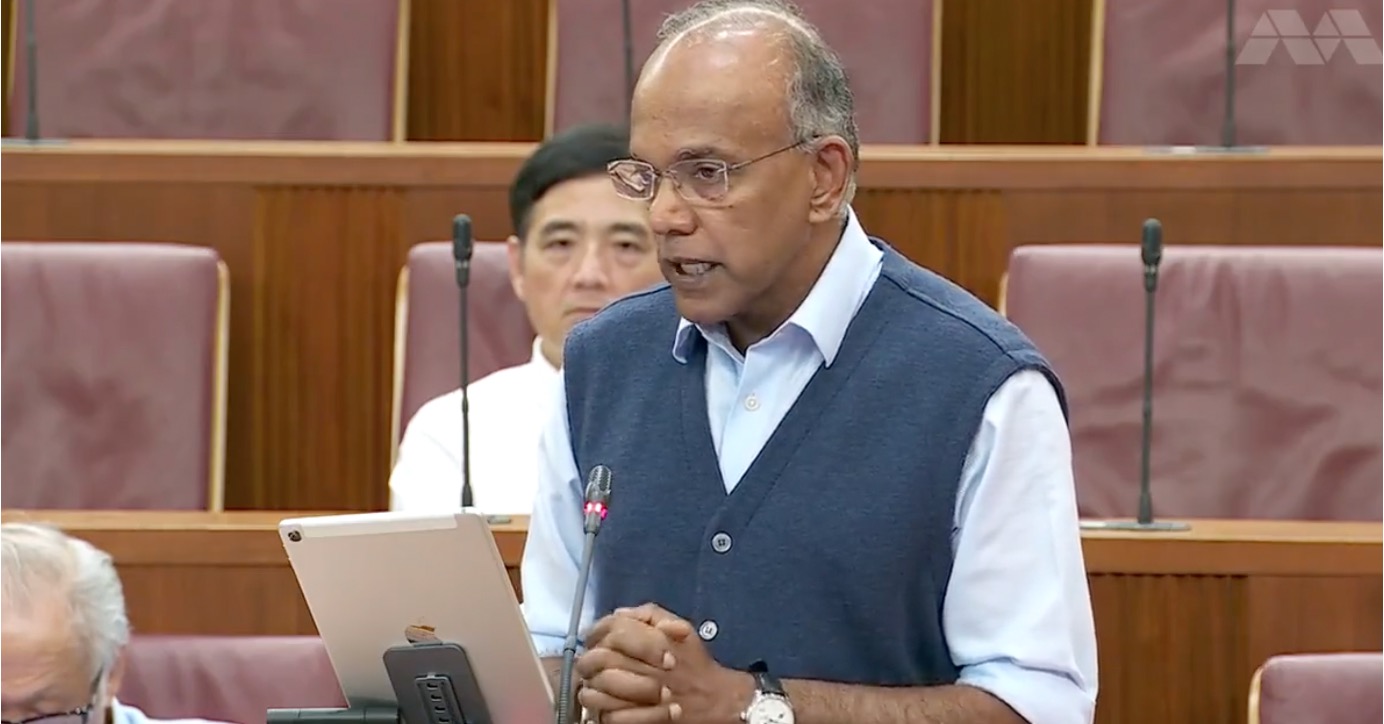

While the issue of homosexuality is a deeply divisive one, gay people deserve dignity and must not be stigmatised, Minister for Law and Home Affairs K Shanmugam said in Parliament on Nov. 28.

"So I say, the time has come for us to remove Section 377A, because it humiliates and hurts gay people", he said.

"Most gay people do not cause harm to others, they just want to live peacefully and quietly and be accepted as part of society the same as any other Singaporean," he added.

Shanmugam also expounded on the legal risks to Singapore's laws if Parliament abdicates its duty and does not act, and Section 377A of the Penal Code is struck down by the Courts in the future.

Historical context for the British law on which 377A is based

Shanmugam said the government had spoken to a wide range of people, including religious leaders and LGBT groups.

He said that many of those who opposed the 377A repeal were concerned about the consequences, and not because they thought sex between men itself should be criminalised.

Shanmugam said that in repealing 377A, one needs to examine the historical context of the law, the "political compromise" that has been struck, and the reasons for moving on the appeal now.

It started with a UK law passed 137 years ago, Section 11 of the UK Criminal Law Amendment Act. 377A is an "almost word-for-word copy" of Section 11.

This was introduced in the UK parliament at 2:30 in the morning, with few other Members of Parliament present, as a last-minute amendment to an unrelated bill, meant to suppress brothels and protect women and girls. That bill had gone through a four year process and already endured a long debate in parliament.

At this point, Member of Parliament (MP) Henry Labouchere introduced Section 11. Shanmugam elaborated on how Labouchere had a history of introducing "wrecking amendments" to discredit laws that others had suggested. Labouchere could also have been extremely homophobic.

In any case, the law that was passed covered all sexual acts between men, including between consenting adults. Perhaps the MPs were tired at the late hour, and just wanted to pass the bill. However, this law in 1885 would go on to impact thousands of lives in the years to come.

In 1938, the UK attorney general introduced 377A to bring it in line with the UK Criminal Law, when Singapore was still a British colony.

King Henry VIII

Shanmugam dug deeper into history, citing the example of the Buggery Act in the 1500s, during the reign of King Henry VIII. This criminalised sodomy, but under church laws, not state.

When Henry broke with the Church in Rome and started the Church of England, he converted many of the Church's laws into secular laws that were handled by the state. This included the Buggery Act.

"When you go through this history, into the origins of the offence of sodomy, we see that it was introduced as part of a power struggle between Henry and the Catholic Church, and not because of any view that sodomy per se ought to be criminalised," Shanmugam said.

He cited two other laws, the Vagrancy Act 1898 and Offences Against the Person Act 1861, which were introduced with no deliberation on whether there was a need to criminalise homosexual behaviour. However, they were retained in the law up till the 1950s.

Wolfenden Committee

In 1954, the UK government appointed the Wolfenden Committee to review laws relating to homosexual offences.

It was only concerned with whether homosexual behaviour should be dealt with under criminal law, and not about private moral conduct, unless it directly affected the public good.

It concluded that the function of Criminal Law was intended to preserve public order and decency, protect the citizens against offence and injury, and provide safeguards against exploitation and corruption of others.

It was not the purpose of Criminal Law to intervene in the private lives of citizens, or to enforce any particular pattern of behaviour aside from the three functions.

The Committee said that homosexual acts in public were against the public good, but such acts in private did not warrant intervention from the law. It also accepted that homosexual sex between men could have a damaging act on family life, which Shanmugam said was something many Singaporeans also believed, and had to be acknowledged.

However the committee emphasised that while it may be considered immoral, it would not be considered as damaging as criminal offences. Therefore it took the position that sex between adult men in private should not be considered a crime.

Northern Ireland's opposition

The public debate on homosexuality in the UK continued. Shanmugam noted that while partial decriminalisation of gay sex between consenting adults occurred in 1967, it only applied to the mainland UK and not Northern Ireland, which was deeply religious and conservative.

It was only decriminalised in Northern Ireland in 1982, following a decision from the European Court of Human Rights. However, Northern Ireland still opposed it and all its MPs voted against the law.

"Northern Ireland’s experience shows how a Court decision can force a change even though a society is not ready for such change", Shanmugam noted.

Division on homosexuality around the world

Shanmugam said that there is a divide in views on homosexuality in the Anglican Church, and the strong viewpoints show:

"First, that even within a single religious community, it is difficult to agree on the 'right' answer, assuming there is one, on the issue of homosexuality. Second, that homosexuality is a topic that continues to raise strong viewpoints. Third, that if we do not handle this carefully, homosexuality can be a deeply divisive issue even among those who share a common belief."

Shanmugam cited the examples of the U.S. and Italy, where even though sex between men has been decriminalised, society still remains divided over the issue.

He added international reporting may gloss over these differences and not understand that such issues need to be dealt with sensitively, with understanding, and they may portray that anyone who has a negative view of male homosexuality is a bigot.

Shanmugam shared some statistics that showed there is a growing international trend towards decriminalising homosexual acts between consenting adult men. But he also said:

"In Singapore, we look carefully at international trends but we don't simply follow such trends. We chart our own path based on what we believe is in our own best interests. And we are very clear to foreign governments and companies, that these are political, social, and moral choices for Singaporeans to decide, and that they should not interfere."

Singapore's history on 377A debate

In 2007, 377A was substantively debated in Parliament for the first time.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong spoke and stated the government's position; Singaporeans as a whole remained largely conservative, and supported stable heterosexual families, but there was growing science-based evidence that sexual orientation is substantially inborn.

While gay people have a place in society and are entitled to private lives, there are different views in society as to whether homosexuality was acceptable or moral. LGBT advocacy should not set the tone for the rest of Singapore society, and the government would try to maintain a balance. 377A would be retained but not pro-actively enforced.

Shanmugam remarked it was a "very Singaporean way" of dealing with the situation which best fitted society at the time.

PM Lee said that if the issue was "forced", it would divide and polarise society and lead to even less space for the gay community in Singapore. Therefore, it was better to let the situation evolve gradually.

"It was a compromise. It was better. And it has worked for Singapore in the past 15 years. We managed to maintain some harmony while many other societies have become deeply divided on these issues for the same period," Shanmugam said.

Why repeal now

Shanmugam said there are two main reasons why the government is moving now on repeal.

First, society is now more ready for the repeal, and it is the right thing to do. Second, there is a significant legal risk that the Courts will strike down 377A if it is left alone.

Repealing 377A is the right thing to do as it hurts the gay community

Shanmugam said that while homosexuality is considered a sin in some religions, not all sins are considered crimes.

"In Singapore, like in many other places, it is generally not the function of Criminal Law to intervene in the private lives of citizens," he said.

Even if 377A is repealed, other laws remain in place that criminalise non-consensual sexual acts between men, sexual acts against young persons, a serious act regardless of consent, and sexual acts between two men in public. These serve to protect society.

However, consensual sex between two adult men in private does not raise law-and-order concerns.

"The time has come for us to remove Section 377A. It humiliates and hurts gay people. Most gay people do not cause harm to others. They just want to live peacefully and quietly and be accepted as part of society the same as any other Singaporean.

They are our family, our friends, our colleagues. They deserve dignity, respect, acceptance. They do not deserve to be stigmatised because of their sexual orientation."

To a gay person, even if 377A is not enforced, it is memorialised in the law, like a sword hanging over their heads. It is a reminder that even in the privacy of their bedrooms, they may be considered criminals. Shanmugam added:

"We have to ask, is it fair that gays have to live in this way? This is not something that we should accept, even if we personally disagree with homosexuality. So, I will say, let us start to deal with these divides, heal these divides and remove their pain."

Shanmugam said that 377A should no longer be in the books, and repealing it makes it clear that gay people are not criminals. However, government needed to manage the consequences of such a repeal.

Legal risk that 377A may be struck down by the Courts

Shanmugam said that if 377A was left alone, there is a significant legal risk that the Courts may strike it down in the future.

It that happens, it becomes a binary process, and the Courts cannot deal with all the legitimate concerns about the consequential effects of the repeal.

Shanmugam explained two court decisions that led to the significant legal risk. The Court of Appeal has dealt with 377A twice in the past 10 years, Lim Meng Suang vs Attorney General (AG, decided in 2014) and Tan Seng Kee vs AG (decided in 2022).

In Lim Meng Suang, the Court made a Procedural decision that the applicant had standing (locus standi) to make the application, as there was a real and credible threat of future prosecution. And even if there was no prosecution, there could be standing, by the existence of a law that is unconstitutional.

However, on the substantive issue, the Court said that 377A did not contravene either Article 9 or Article 12 of the Constitution, and Lim Meng Suang was dismissed on the substantive basis that 377A was not constitutional, even though the applicants had locus standi to bring the challenge.

377A was challenged again in Tan Seng Kee, arguing that 377A contravened Articles 9, 12 and 14 of the Constitution. The Court of Appeal dismissed the challenge, but it was dismissed on Procedural grounds and did not rule on one of the Substantive grounds.

It therefore reversed itself on the locus standi point, because the Attorney General said that absent other factors, there would generally be no prosecution under 377A, where the conduct was between two consenting adults in a private place.

As 377A was unenforceable until the AG gave clear notice that he intended to enforce it, so the applicants did not face any real and credible threat of prosecution, and therefore had no standing to bring the case. One Court of Appeal can disagree with another.

Substantive ruling

Although the Court of Appeal did not need to give any view on the substantive merits of the challenge, as it decided that the applicant had no standing, it did so anyway.

While it decided that 377A did not contravene Articles 9 and 14 of the Constitution, there were two ways the "reasonable classification test" could be applied to Article 12, the Equal Protection clause.

The Court said that if the approach in the 2021 Syed Suhail case was adopted, then 377A may fall afoul of the reasonable classification test, and 377A would probably be unconstitutional if the Syed Suhail test is applied.

The Court of Appeal has since applied the Syed Suhail test in other cases, including in 2022. It suggests that if another constitutional challenge against 377A is brought before the court, the Syed Suhail test is likely to be applied.

And if that test is applied, 377A is likely to be struck down on the grounds that it breaches Article 12 of the Constitution.

While some may argue that it may not happen as long as the AG says it will not enforce the law, Shanmugam likened it to letting a small boat sail into choppy waters surrounded by rocks and hoping that it won't crash against the rocks. There exists the possibility that a future case may have standing for an application, as the Court of Appeal could change its views in the future.

Shanmugam added:

"So, let us be clear. One, after the Tan Seng Kee judgment, Section 377A is at significant risk of being struck down in a future challenge and two, we cannot simply hope that the point on locus standi is enough for the Government and Parliament to do nothing.

That will be just wishful thinking. And wishful thinking is no substitute for careful legal analysis or proper policy. If we engaged in wishful thinking, and if Section 377A is struck down in the Courts. That could lead to a whole series of consequences that could be very damaging to Singaporean society."

If Parliament does not act, the courts may have to act

Shanmugam pointed to the example of the Indian Supreme Court, which ruled their own version of the law unconstitutional in 2018. The Indian parliament did not move to repeal or amend the law, even after a court decision in 2013 said parliament was free to do so.

The supreme court held that the Indian parliament's failure to act was not a good reason to prevent the supreme court from striking it down. Shanmugam said:

"What is the lesson here? When Parliament does not act, when it should act, then we may leave the Courts with no choice. If fundamental Constitutional rights have been violated, and yet Parliament abdicates its duties, then the Courts may have no choice but to act."

If 377A is struck down by the courts, it may lead to laws that are based on the definition of marriage between a man and a woman being challenged in the future.

Despite the judiciary making rulings on social issues in countries like the U.S., in Singapore, the Courts recognise that Parliament is the better branch to resolve difficult social issues, as elected members. Considerations beyond the law may be taken in, unlike the Courts.

Shanmugam emphasised that Parliament has a duty to deal with laws that may be unconstitutional. And if Parliament abdicates its duty, then it may leave the Courts with no choice, and they will "have to do what they don't want to do."

Government has a duty to deal with this issue in Parliament

Shanmugam said that leaving it to the Courts would be the path of "least resistance", and approaching this purely on a political basis, concerned only with votes, making as few people as possible unhappy, would have been easier.

However, as elected representatives of the people, they cannot do this.

"If we see a risk that a law may be found unconstitutional, it is our duty to act and deal with it in Parliament. Both because it is our duty to do so, and because taking the easy way out would have negative consequences for our society. It will be very bad for Singapore," Shanmugam said, elaborating that a strike down could lead to cascading effects on housing and media policies, for example.

He concluded:

"I want to emphasise this. I had given two reasons for proposing the repealing of Section 377A. We should do so because there are no public order issues that are raised from such conduct, so it should not remain criminal. But I accept that MPs and others, may disagree with that. That even though there are no public order issues, they may feel that there are other reasons for keeping the law. And I accept that people can and do legitimately have such views, and it is reasonable to hold such views.

But the second reason I have given, the legal consequences, that is not a matter of conscience. It is a policy question. It requires each of us to think carefully and apply our minds. The second question is matter of considering the consequences for Singapore. Given that there is a clear legal risk that Section 377A could be struck down. And given that, having heard me, you know what the consequential legal risks are, in fact this has been talked about in public, about the consequential legal risks to the heterosexual family, housing, education, other policies. They could all be at risk.

Knowing all these risks and refusing to take a position, or be clear in how we will deal with it, is avoiding our responsibilities as MPs, basically passing it on onto the Courts. It is easier, politically. But it is also worse for Singapore and Singaporeans. And to put it bluntly, that is an abdication of duty. And it would be cynical if we as MPs did that. Because we would be putting...political capital over doing what is good for Singaporeans."

Top image from MCI YouTube.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.