Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Annie’s new flat is large and airy.

Natural light floods the vast living room, and floor-to-ceiling windows open up to an unblocked view of the Sentosa coast. There’s plenty of space, enough to accommodate her children as they grow. It’s a perfect fit for her young family of four.

Of course, her “dream house” (as she puts it) doesn’t come cheap: the 1,140 square feet unit at the Pinnacle@Duxton Housing and Development Board's (HDB) estate comes with a hefty price tag of S$1.34 million.

The homeowner is not using her real name in this story.

Once a novelty in Singapore’s property market, such million-dollar HDB flats have today become a dime a dozen, with new transactions seemingly announced every other day -- 111 million-dollar HDB flats changed hands in the third quarter of 2022 alone.

But exactly who are the people buying them — and more importantly, why?

Back to beginnings

Before we go into that, let’s backtrack a bit.

It’s important to note that this phenomenon is more than just another blip in the property radar, eliciting a range of fairly strong, often pretty negative reactions from Singaporeans.

To understand why, let’s delve a little into the history of the HDB flat. Under the governance of the then-prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, the HDB was launched in 1960 to house the citizens of the fledgling nation — which was, to put it lightly, kind of a mess.

Most people resided in overcrowded slums and squatter settlements, which in turn caused tensions between social classes. This only worsened as the population rose post-war. "People were poor and life was hard," PM Lee recalled, speaking at the key handover ceremony of Pinnacle@Duxton in 2009.

"No running water, no modern toilets, no expectation of a better future... our future looked bleak."

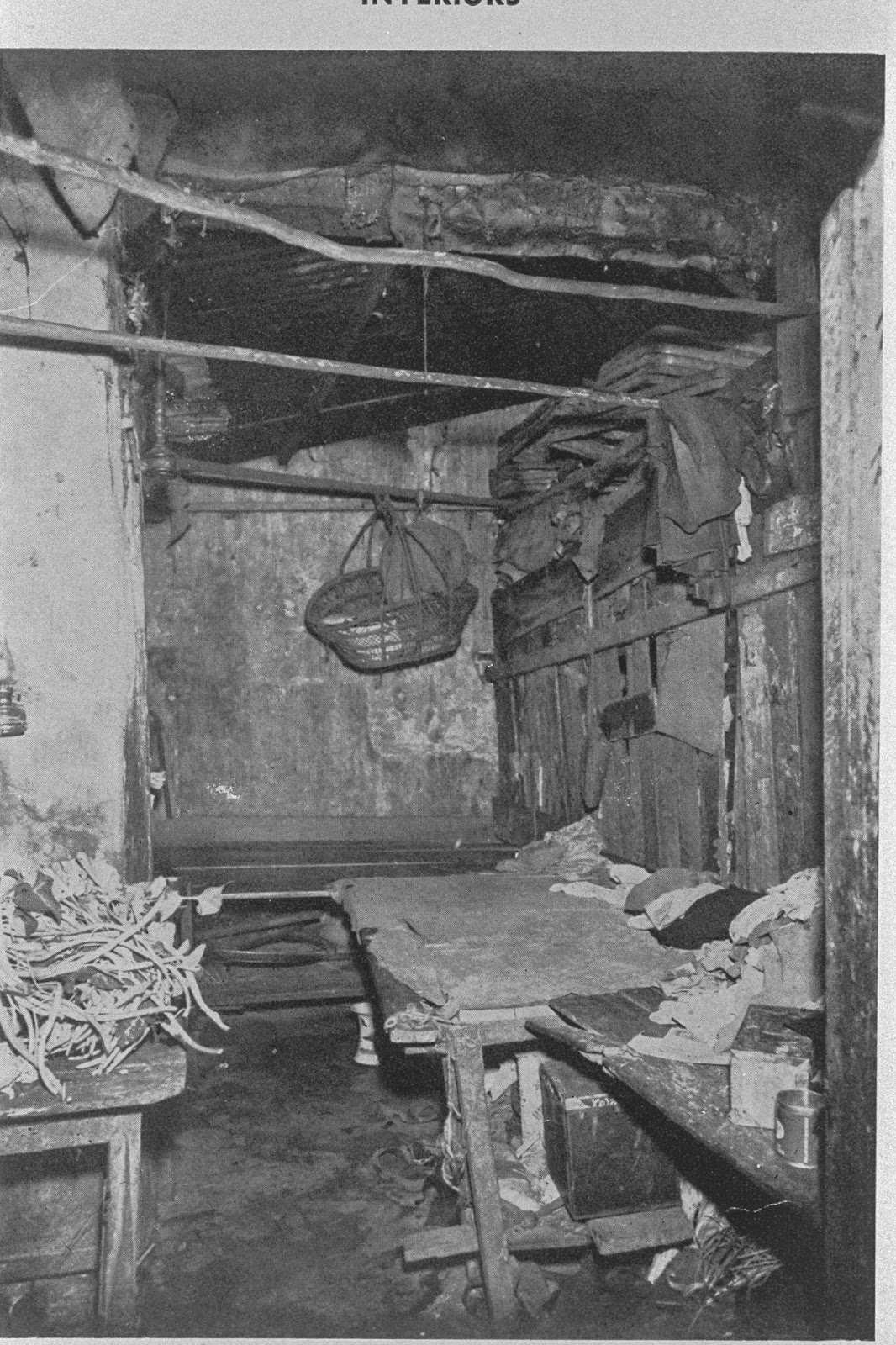

Interior of an urban slum (kampong) at Bukit Ho Swee, taken in 1947. Photo from National Archives of Singapore.

Interior of an urban slum (kampong) at Bukit Ho Swee, taken in 1947. Photo from National Archives of Singapore.

Still, his government took to the task with breathtaking efficiency, housing the population the true Singaporean way: "progressively and systematically", as he described in his speech.

To this day, it remains one of Singapore’s greatest success stories; upon inheriting Singapore from its colonisers, only 9 per cent of the population resided in public housing and by the 1980s it was 85 per cent.

But it doesn’t end there. In 1964, the government introduced the Home Ownership for the People scheme, the first PM’s next step towards his vision of “a home-owning society”. By the time he stepped down in 1990, Singapore’s homeownership rate had hit 88 per cent.

With such a history, it’s not difficult to understand the angst. The HDB flat has always been synonymous with housing that every Singaporean could aspire towards. Affordability and accessibility are, at risk of sounding dramatic, its literal reason for being.

But with million-dollar flats popping up all over the place — most alarmingly, in non-central, heartland estates like Bukit Batok and Yishun where housing has historically been the most affordable — is the heart of the HDB set for change?

The marginal buyer

Short answer: probably not.

At least, that's what Sky Seah — a senior lecturer at the National University of Singapore's Department of Real Estate — believes.

The latest slew of property cooling measures, announced in late September, come as a sign that the government fully intends to keep housing affordable, says Seah.

"I think that it’s a very strong signal that they really want to make housing affordable, and they don’t want to have runaway prices as a norm for sure," she explains.

"That's a very key policy that [the policymakers] want to maintain — to have those high levels of homeownership, so that nobody gets priced out by the market."

But why the need for such cooling measures in the first place?

According to Seah, it's because the market has moved to a point where average or median prices are no longer what the majority can afford, running a course she admits seems "baffling".

And the culprit? A party — or rather a phenomenon — called the "marginal buyer".

This basically refers to the people with the ability to bid the highest, Seah explains. In a free market, transaction prices are determined by how much buyers are willing to pay for a good or service.

Where there is one unit and more than one interested buyer, there becomes "something like a highest bidder situation". Basically, the owner sells the unit to the highest bidder: the marginal buyer.

That's just economics. But the real problem today is that the marginal buyer is no longer representative of the average Singaporean, Seah says.

The result: runaway prices, unexplainable by market fundamentals, that are beyond the average Singaporean's purchasing power.

There's no singular reason for the emergence of these market-disrupting marginal buyers. Some might be higher-income couples who prefer not to wait for a BTO, amid increasingly lengthy wait times; others may be affluent singles who previously weren't able to buy an HDB under the old (and less restrictive) Singles Scheme.

Many, Seah theorises, may be private property downgraders cashing out and entering the resale market.

Whatever the reason, the government has introduced some cooling measures to rein in the market, including a 15-month wait-out period for private property downgraders looking to buy a resale flat.

It essentially creates a barrier between the resale and the private markets, so homeowners can't just take the capital they get from one market "and basically set record prices in the other market," Seah says.

“I think that this cooling measure is to signal to sellers: don’t think that there’s so many marginal buyers out there who can pay these high prices," she adds.

"And I do hope that in the short run, with the cooling measures, that the prices will be moderated. Because I really don't think that it is sustainable, this rate of increase... at all."

A forever home?

For context, I recently bought my first HDB flat (sadly not a million-dollar one).

At this point, I was beginning to see a major incongruity between the behaviour of these marginal buyers and my own. Namely, why would anyone spend a million dollars on a government-owned flat, just because you have the cash?

After all, as old folks (read: my parents) are fond of pointing out, property is an investment.

And with a million-dollar budget, wouldn't private property surely have much better investment potential than an HDB flat at peak price?

Well — yeah. According to veteran realtor Kas Chen, 32, the buyers of these flats aren't looking to make bank.

Rather, they have a list of things they want in a house, like space or location, and are just looking to get the biggest "bang for buck".

Take, for instance, a young family hoping to live in the trendy, centrally-located district of Tiong Bahru. A mid-sized condominium might cost upwards of S$1.7 million, while a larger, younger HDB flat would cost much less.

With a million-dollar budget, they could squeeze into a smaller private unit with better profit potential — or they could just skip out on the earnings and get their dream house.

The view from a 4-room HDB flat at Henderson, which sold for S$1.055 million in 2021. Photo courtesy of Kas Chen.

The view from a 4-room HDB flat at Henderson, which sold for S$1.055 million in 2021. Photo courtesy of Kas Chen.

A decade or two ago, the decision would've been obvious, erring on the side of financial prudence. But with increased affluence and general prosperity, an increasing number of people no longer feel the need to profit off their property, Chen explains.

“You’d be surprised, not everyone wants to make money from selling houses," she tells me. "There are people who don’t need to make money from their home... a lot of downgraders, retired people. ‘This one, I buy, I live comfortably’."

"They just want a good place to live and grow.”

"To a lot of the masses, getting a home is like forever. They don't really need to aim and sell," she adds.

"So it’s not so much for investment... but mainly for [the buyer’s] own stay over a longer horizon."

Willing buyer, willing seller

So now, going back to the first question — who are buying up these flats?

It’s a question best answered by realtor Joanne Lee, who has sold 10 S$1 million units in the past three years (Annie’s will be the 11th).

In her experience, buyers tend to fall into one of three main groups.

The first are seniors, typically around retirement age. No longer having any use for swimming pools and tennis courts — facilities which may have lost their appeal after their children leave the nest — they’re now looking to trade in their private property for money in the bank.

The second group are what she calls "pre-private upgraders" — high-income earners, often without children, looking to move up the property ladder from an HDB to a condo.

View from a unit at Pinnacle@Duxton, which sold for over S$1 million. Photo courtesy of Joanne Lee.

View from a unit at Pinnacle@Duxton, which sold for over S$1 million. Photo courtesy of Joanne Lee.

Finally, there’s the third group, which Lee says makes up the majority of her buyers: dual-income, young couples with parental support.

In terms of motive, they differ in one key way from the other two groups: they're buying for sentiment rather than cold-hard functionality.

These couples tend to prioritise living near their parents; but when their parents stay in mature estates with a dearth of affordable housing, and especially if the couples are younger with fewer savings — "[the parents] will actually support the down payment," she tells me.

Of course, in some cases, it's a matter of simple convenience. With dual-income households pretty much the standard these days, grandparents are increasingly involved in childcare. Mature estates also tend to have more amenities, like MRT stations, supermarkets, and polyclinics.

But Lee says it's really more about the sentiment — the desire to stay close to family, and to remain in the same environment in which they grew up.

"Willing buyer, willing seller," she summarises. "It's human nature that you will fall back to familiarity... familiarity in a school, in an estate that you grow up with."

As a result, whether in a central location like Queenstown or in the heartlands of Bukit Batok, Lee foresees that people will continue to pay for this privilege of sentiment as long as they can afford it.

And the numbers don't lie — as of Sep. 25, over 266 million-dollar HDB flat transactions have been recorded, of which only 12 were located in non-mature estates, reported The Straits Times.

But while the new cooling measures might help stave off the worst of the heat, Lee firmly believes that million-dollar flats aren't going anywhere.

"As long as the market is moving upwards, there will always be people with genuine needs," she tells me.

"And as long as there’s genuine needs — people needing to be near their support system — there will be more S$1 million HDBs coming up, beyond the central region.”

"I found my dream house"

In Annie’s case, the ink hasn’t yet dried on the Option to Purchase. But already she is full of ideas.

Her two children will each have a bedroom of their own (they’ve both seen the flat, and have given their stamp of approval). The slightly dated interior, a relic from the unit's first owner, will have to be revamped.

Most importantly, it's just a stone's throw away from her parents' flat.

Her excitement is effusive, and it’s no surprise: this will be the 47-year-old’s first home of her own.

For the past decade, Annie and her family have been staying in her parent's flat at the Pinnacle. That familial attachment made it an easy call to set proximity as a prerequisite when, half a year ago, she began looking for a home of her own.

Besides, “my parents help me to look after my children, so it’s more convenient if we stay together," Annie adds. With these advantages, her S$1.34 million flat seems, against all odds, like a pretty good deal.

Naysayers may warn against its investment potential, but Annie isn’t deterred. The flat is a forever home, she says — one for her children to grow up in and one that fits all her young family’s needs.

Because finally, after 10 years — "I found my dream house," she says.

Top image adapted from photo by Modern Affliction via Unsplash.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.