Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Here are some meals served to full-time national servicemen (NSFs) in Pulau Tekong over the past few years.

Granted, these are nice pictures of "special occasion" meals. But still, not bad.

Of course, if you eat these meals about five times a week, please feel free to disagree vehemently.

But what was the food like before professional catering services?

The comment sections of posts about special meals in at the Basic Military Training Centres (BMTCs) are often rife with former NSFs regurgitating horror stories of unpleasant meals of National Service's past.

And yes, of course, standards might have fluctuated throughout the years, but there seem to be one or two defining moments in cookhouse history — watershed moments for food quality.

Privatisation

On a now-deleted page on the Army Museum section of MINDEF's website, there's a timeline showcasing interesting facts about army culture.

This part:

Private caterers. Nice.

While the considerations might have been happening in 1984, the full implementation of private catering would take place only over 15 years later.

Ah boys to cooks

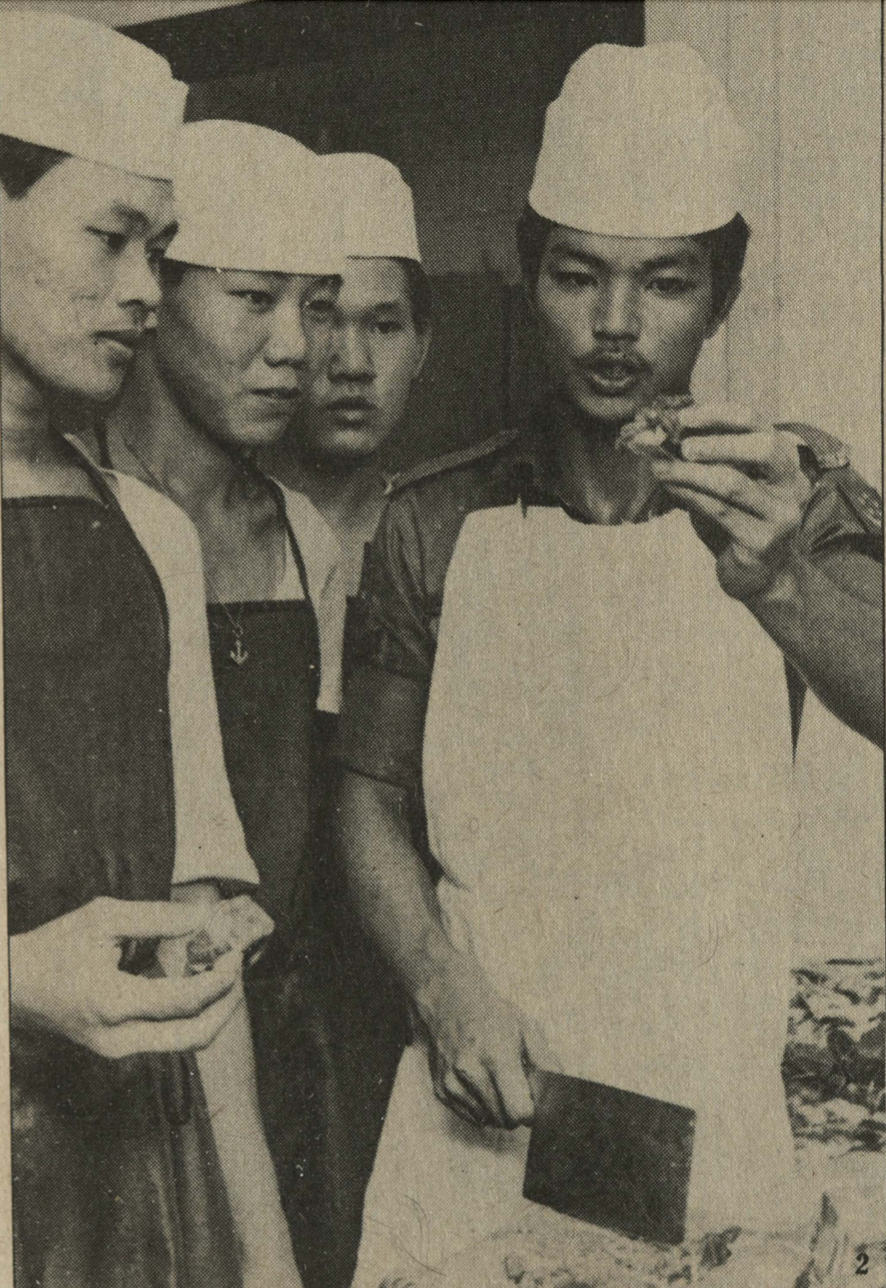

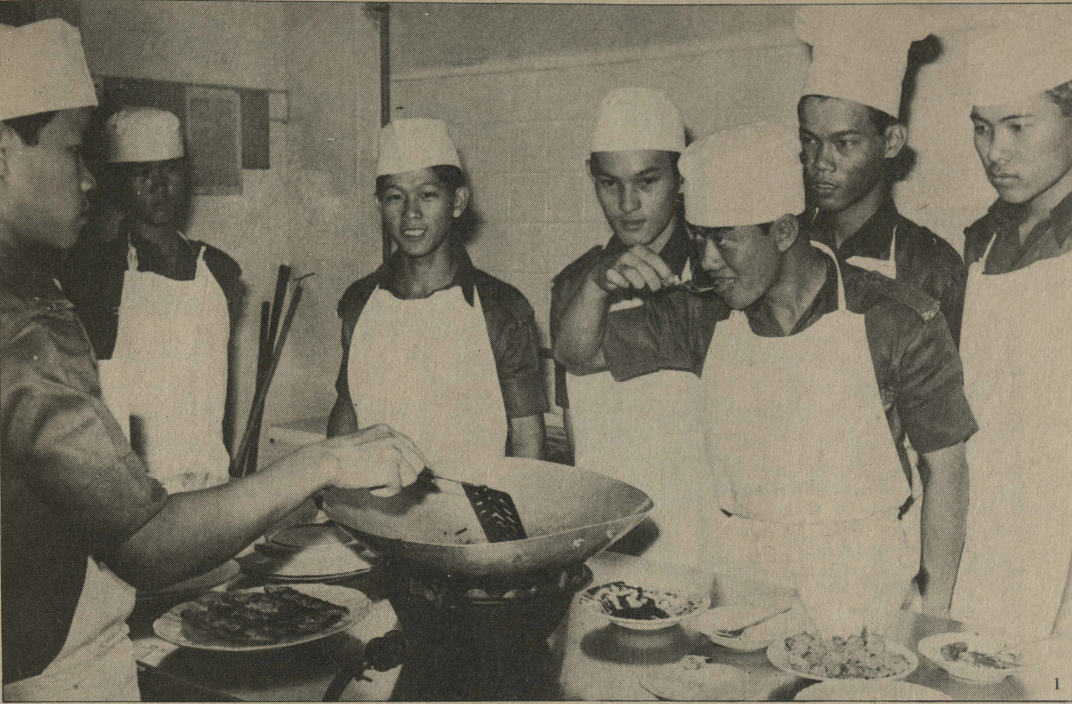

But before the dawn of private caterers, the army cookhouses were squarely the domain of the National Servicemen.

Like most vocations in the army, some recruits were selected for the role of cook, fresh out of BMT.

These chosen cooks were then trained at the School of Army Catering (SAC). There, they underwent an eight-week "intensive course".

Their first few lessons covered how to identify utensils and ingredients, as well as learning different cookery terms.

If you are wondering whether you can learn the intricacies of cooking for a massive number of hungry, bald teenagers in eight weeks, put that worry to rest. You absolutely cannot.

Captain Wong Soon Yoke (you'll be seeing his name a lot), the head of the SAC, laid out what the eight weeks would be used for.

"We can only teach them the basics in this course and send them out with a list of recipes."

After eight weeks, the recruit, armed with a handful of recipes, is now a Class 2 cook.

There will be opportunities for some of these cooks to get a Class 1 certificate later in their NS life, but for now, they are off to different units to feed a ravenous bunch of boys/men.

What to eat?

But what were they going to feed them?

The cooks were mainly taught recipes during courses, and they could sometimes be called back to SAC to learn additional recipes.

According to an article by Pioneer, the cooks in the Class 2 course learnt to whip up dishes like chicken stew, fried pak choy, fish lemak, fried turnip, egg sambal and tow hoo soup.

The ones with more cooking experience enlisted in the Class 1 course and were taught how to make char siew, pak cham kai, chap chai, chee pau kai, roti prata and kueh dadar.

Screenshot from Pioneer Magazine

Screenshot from Pioneer Magazine

The Class 1 course also ended with a real doozy of a final task.

A 20-dish marathon where the candidate had to produce a selection of "Chinese dishes, stews, curries, pastries and desserts" in five hours.

Screenshot from Pioneer Magazine

Screenshot from Pioneer Magazine

Even though cakes and pastries weren't standard SAF fare in the 70s, SAC included pastry making in some of their courses.

However, these skills were not entirely wasted, as cakes and pastries were sometimes served during festive seasons.

So even in the 70s, the food choices didn't seem too terrible.

It wasn't Oliver Twist-ian levels of minimal gruel and maximum cruel, but more like a mediocre coffeeshop's menu.

But as anyone who has talked to an older Singaporean about his army days would know, the food wasn't just mediocre; it was "talk passionately about how terrible it was nearly 50 years later" bad.

Why was it bad then?

An oft-overlooked part of the NS cooking experience was the cooks themselves.

Being an NS cook was not always the flashiest profession. In fact, Wong (the head of SAC) talked about the various challenges associated with the vocation.

"In the beginning there weren't many boys who were interested in being cooks"

There were even considerations early on to assign sergeant ranks to army cooks to attract more manpower.

But unlike a vast majority of NS vocations, where the core components of their NS training are applied within active service (and pockets of reservist call-ups), some of these cooks had a bit of experience in the kitchen before coming into NS, and carried on as a cook afterwards.

As Wong pointed out:

"...many of my ex-students after completing National Service have taken up jobs as cooks in leading hotels."

In fact, the students would muse to Wong about how odd it was that they could "produce such lovely food in the hotel" but "fail dismally" when cooking for the army.

The main culprit was sheer volume.

It's one thing to cook a nice dish for a hungry diner, quite another to push out meals for an entire army. This was the case even with the 1,200 army cooks they were training a year by 1977.

Private Tay Seng Kee told Pioneer about the challenges of cooking for so many people:

"There is no time to concentrate on just the right ingredients for taste. When you cook vegetables in a cauldron-sized kuali and with a paddle-seize ladle, the best you can do is concentrate on a generally acceptable standard and on hygiene."

This wasn't some sentiment murmured in the dishevelled bunks of disgruntled men either. Captain Wong pointed to the same thing as well in New Nation's piece, "Food for thought: Why it's not so tasty in the mess":

"Even good, experienced cooks find it difficult to produce tasty food when they have to cook for masses, so it is no surprise that army cooks do not produce wonderful food"

And cooks didn't just have to deal with mass catering. They were responsible for every step of the cooking process. From washing dishes to budgeting food...

"The boys are also taught to be budget-conscious since working within a budget is an important aspect of army cooking."

...to serving as quality checkers for cookhouse ingredients during the army's earlier days.

This even led to food contractors bribing cooks to accept "inferior quality" vegetables.

All this to say, these cooks were doing a lot, and the diners were suffering for it.

Reception to the food

Everyone who knows an older serviceman would know second-hand how bad the food was by the anger that flashed across their eyes.

But just how bad was it?

It's tough to give a precise score because of the relative lack of contemporary literature about cookhouse food back then.

There are plenty of gripes written in retrospect, though.

Notable personalities in the food scene like MakanSutra founder KF Seetoh, ieatishootipost's Leslie Tay and Daniel Ang of DanielFoodDiary have all given some measure of what they felt about the food back then.

Seetoh described his first meal at BMTC as having to choose between "plain steamed horrible bread with flavourless egg" and fried bee hoon he described as "fried rubber bands".

You can also find bits and pieces of anecdotes here and there over the decades detailing just how terrible army food was.

Take this one random forum letter from 2007 by one Ezekiel Lim on NS.

In the midst of a broader point about the positive traits NS had inculcated in him, Lim recounted the food they had in the army back in the 70s.

According to Lim, they "had to tolerate" the food prepared by the army cooks. But even their commendable patience had limits.

Their arch nemesis was noodles. Specifically the noodles they had for breakfast.

Lim said the cook who prepared it "couldn't decide whether to make it dry or wet".

The result of that fusion cooking?

"After eating it, there was always a long line for the toilets."

It was so bad that they had to raise the issue with their then-Platoon Commander, Lee Hsien Loong, who was leading the platoon for a couple of months.

Lee subsequently responded to this letter, saying that it was heartwarming to hear from old soldiers who have served with him.

NSF cooks recounting their experiences

Mothership talked to two people who were NSFs in the NSF cook eras of the 70s and early 80s.

Here are some choice samplings of how they described the food then.

Rice was too hard, vegetables sometimes had soil, and the chicken was either too hard or burnt.

All in all, not exactly a ringing endorsement.

Also, they noted that despite the relatively wide-ranging recipes mentioned above, quite a few of the meals were either fried mee or fried bee hoon.

Praise of the food in reports from those days, when there were any, was quite tempered, usually toeing the lines of hardworking cooks giving it their all, with two rather notable exceptions.

One was a glowing review by a British army chef comparing their standard of cooking to "some hotels in Singapore".

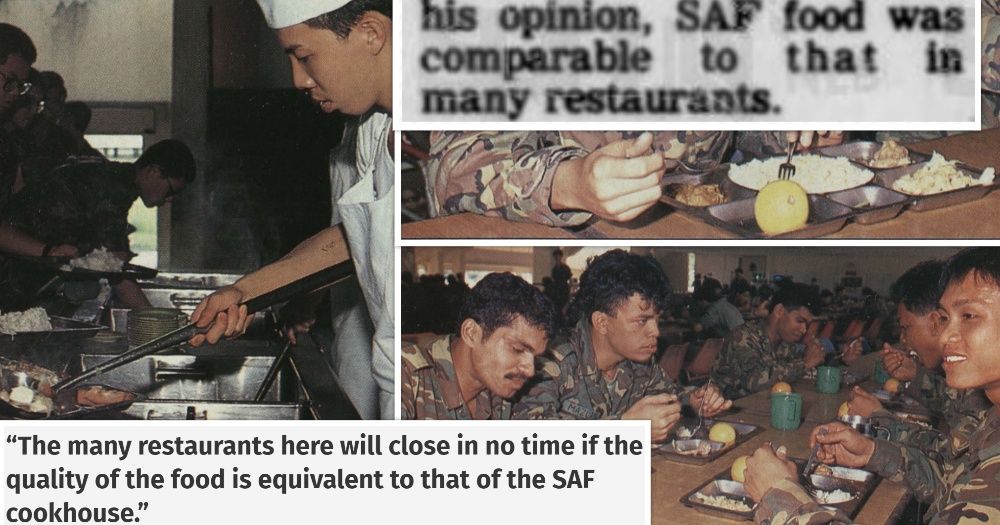

The other was in 1982, during the opening of a S$6 million Singapore Food Industries coldroom and warehouse complex (more on this later), when then-Minister of State for Defence Yeo Ning Hong said that he had eaten meals "from the same pots" as the officers and men in the SAF.

Yeo said, in his opinion, SAF food was comparable to that in many restaurants.

Hmmmm.

But before the dark times of overworked cooks ended completely, there was one more notable shift in the kitchens.

Transition to reheating

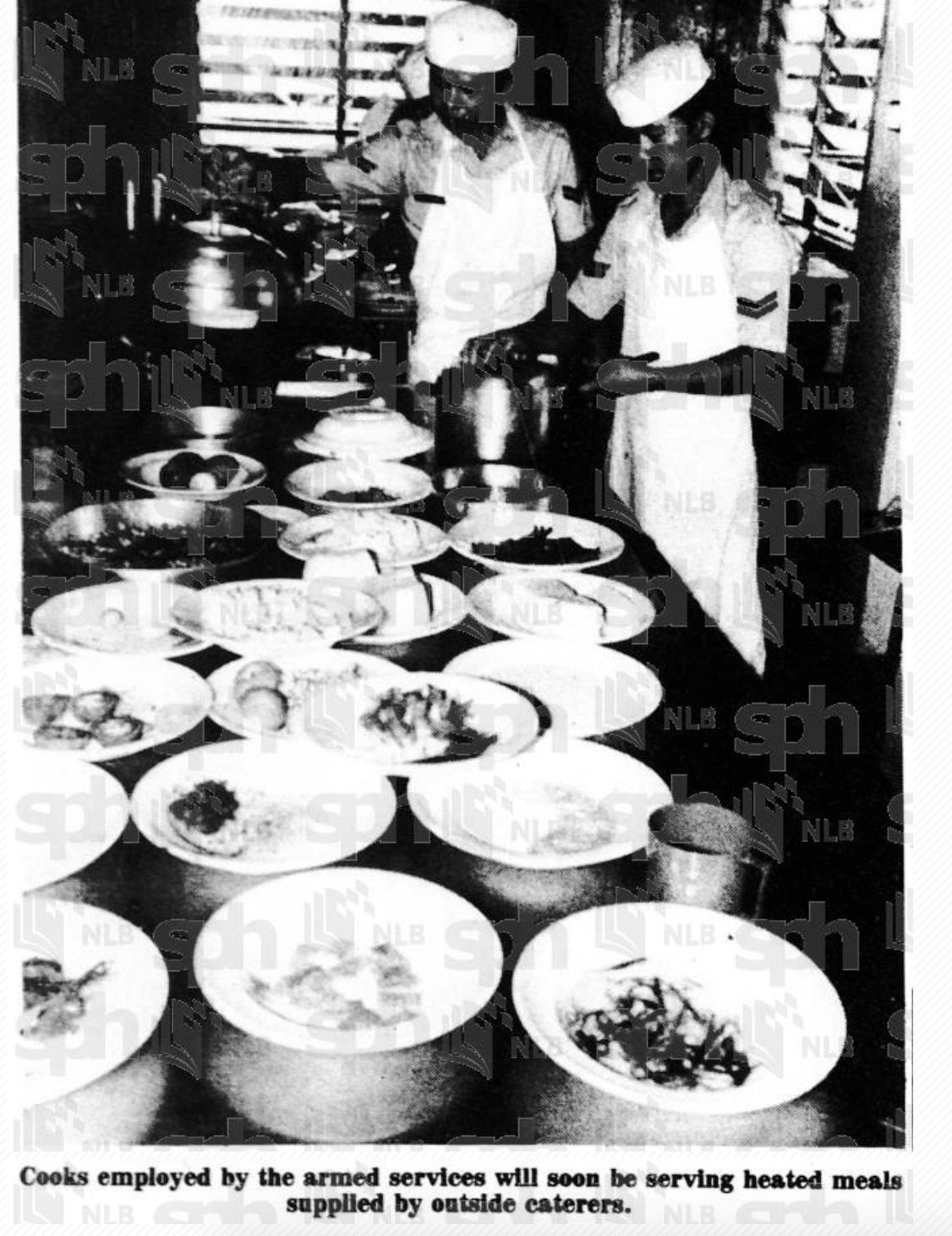

The 80s was a time of significant change in how the army cooked their food.

While not yet deploying a full catering system, cooks were very much still involved in the day-to-day operations, as the process became more about reheating pre-cooked food.

In 1985, tenders were called for pre-cooked food supplied by outside caterers.

The plan was to supply enough food for four meals daily for 5,000 men in the first year and 20,000 men in the subsequent three years.

Of course, all these were just interim measures till a full-time catering system. But it had quite the impact on the NS cooks.

Here's basically how the new system worked.

Caterers would cook the meal off-site. Meals would then be collected by personnel from various camps twice a day (once a day on weekends and public holidays).

Dinner and night snacks were picked up in the morning, and the next day's breakfast and lunch were picked up in the afternoon.

The food would then be stored in cold rooms and reheated before serving.

The surveys at the camps where the new system was implemented apparently showed 56 per cent of the men favoured pre-cooked meals. It isn't specified if a catering staff was standing beside them as they gave their scores.

But it wasn't like this was some panacea to all the disgruntlement about the food quality.

In fact, the cooks weren't all too chuffed about the new preparation system either.

Calvin Koh was a cook in the army from 1992-1994.

Falling smack dab in the middle of one of the last years of the NS cook.

He is one of those many success stories illustrated by Captain Wong. An NSF cook who went on to bigger and better things in the culinary world.

Koh became a station chef at Pan Pacific out of NS, before eventually rising to Executive Chef at AccorHotel. He is currently running his own eatery, CK Cuisine at ITE Headquarters, Foodgle Hub.

Good ratings too.

But like every cook before him, Koh had a rather bad go in the army cookhouses.

Speaking to Mothership, Koh noted just how little room they had to experiment.

While the NS cooks of the 70s and 80s were not exactly crafting menus and experimenting with fusion food, the last batch of cooks was for the most part, just reheating the prepped food.

Koh was not a fan of the tray reheating system, saying he preferred cooking the food from scratch.

A major gripe he had was with the smell from reheating the trays.

But that reheating phase of the army didn't last long.

And by the end of 1998, every single cookhouse in the army was run by private caterers.

Pragmatism and food

These watershed moments might serve to bookend different generations of army personnel, with the inevitable comparisons being made across generations.

Phrases like "last time the food was so much worse" might be technically true, but misses out on the more pragmatic forces that ultimately led to change.

The most significant push behind the outsourcing of cookhouse food was manpower limitations.

As the number of enlistees shrunk, the need to free up manpower became more pressing.

Therefore less cooks.

An oft-repeated talking point by older folks I talked to was how terrible the food was because of the cooks. Was that true? Yeah, maybe.

But remember, many of these cooks went on to become really impressive chefs in their own right. So it wasn't like they didn't possess talent or love for cooking.

These burgeoning chefs were just being asked to cook for hundreds of tired, grumpy enlistees, they were also responsible for administrative decisions like buying ingredients, waking up at ungodly hours to prepare breakfast, and all this with just a few weeks of training.

So in summation, no one was having a good time.

The relatively better experience of improving food quality is a likely consequence of pragmatism. It is not because food quality was improved for this supposedly weaker generation.

Because if some of the top brass back then thought the food was comparable to restaurants, what was the impetus to make it better?

Interestingly enough, Yeo's restaurant comment peeved off one Steven Yong so much that he took to the most proven method of rebuttal back in pre-social media days, the ST forum.

In an acerbic piece titled "when to find out about army food" Yong suggested the Minister conduct surprise visits to cookhouses.

"Let us however face the fact that the food Dr Yeo tastes during his rounds is specially made by the same cooks. Dr Yeo should make a survey of how many soldiers praise cookhouse food. He should pay a surprise visit to any camp in the evening to taste the food there."

Rounding off with this observation:

"The many restaurants here will close in no time if the quality of the food is equivalent to that of the SAF cookhouse."

Other Motherlong articles

Image adapted from Pioneer Magazine

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.