Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

It was near the start of his first year in polytechnic when Wayne Chan set his eyes on his “holy grail” watch – a Rolex Submariner worth about S$11,000.

For two and a half years, Chan saved every cent from his internship pay, his Chinese New Year and birthday ang paos, and even took on part-time jobs during school breaks to save up for the watch, aiming to purchase it before he turned 21.

His batchmate and friend, Brandon Fong recalled: “He didn’t want to eat lunch with us. He’ll say he needs to save up. Quite a journey.”

Now a student at the National University of Singapore (NUS), Chan managed to buy the watch a couple of weeks before his 21st birthday, a proud moment for him.

A luxury watch is a significant expense for most, and naturally, the hobby of collecting them is not something everyone can easily afford.

Which begs the question: Is watch collecting an expensive hobby just for the rich?

An expensive hobby

As Chan’s story illustrates, getting a watch is a big financial commitment.

Chan has a collection worth about S$19,000, including his Rolex Submariner.

Rolex watches are priced anywhere from S$6,000 to over S$40,000.

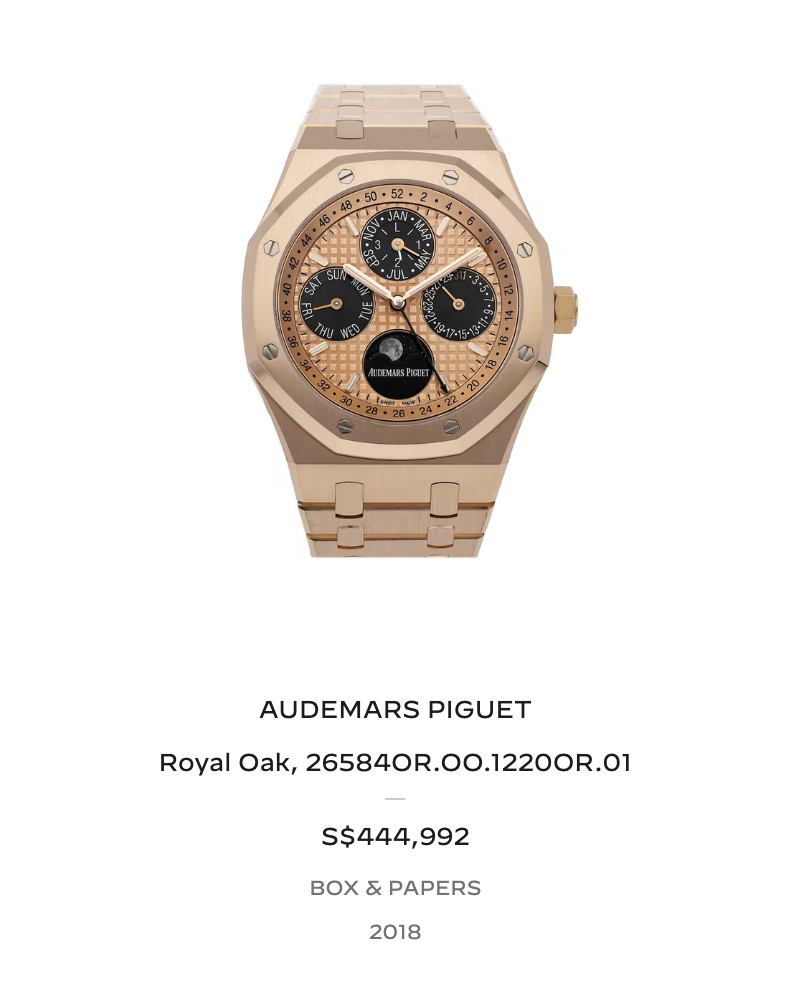

An Audemars Piguet (AP) Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar Limited Edition costs S$444,992 on Watchbox, an e-commerce platform for pre-owned luxury watches.

Need I go on?

Collectors with multiple luxury watches likely have a collection worth tens or hundreds of thousands, maybe millions – an amount some enthusiasts are willing and able to pay.

What is the value these collectors see?

Rolex prides itself on the fact that its watches are mostly assembled by hand, from their movements to their bracelets.

Image from Rolex website.

Image from Rolex website.

What’s fascinating is how these watches, without an electrical circuit, function with the moving of their springs and gears and nothing else.

With all that intricate craftwork, it's not surprising that each Rolex watch takes about a year to make.

Image from Rolex website.

Image from Rolex website.

German watch brand A. Lange & Sohne told Forbes that it takes six months to over two years to make their watches, depending on the complexity of the make and design of the timepiece.

The Federation of Swiss Watch Industry says that price disparity between watch models and brands is “justified” for several reasons — the type of cases used, the choice of crystal for the watch’s dial, and its bracelet band.

These explain why watches are pricey; those who collect them value the craftsmanship.

Chan was also drawn to the work of watchmakers around the world but couldn’t afford a watch with such a hefty price tag at the start of his watch-collecting journey.

His first watch

Chan bought himself a watch — a Casio G-Shock — when he was 17.

To him, choosing a watch for himself was a mark of stepping into adult life. Seemingly, it was a common mindset among his friends who were doing the same at that age.

Quickly, his enthusiasm for watches grew. He started learning about mechanical watches and got hooked.

“These watches have no batteries, I was fascinated,” Chan said. His co-worker at the time recommended a Seiko watch — which cost around S$200 — as a good first mechanical watch.

And it became his goal to save up and buy it by his 18th birthday, which he managed to do.

Chan's first Seiko watch.

Chan's first Seiko watch.

Owning his first mechanical watch inspired a different feeling.

Unlike his Casio watch, Chan could see the gears and wheels oscillating through a clear case, and he became fascinated by how the mechanism drove the watch’s hands to move so precisely. Chan said:

“The oscillation kind of reminds me of a beating heart because like how the heart pumps the blood to the whole body, this oscillation is what drives the hands to move. I think that's cool.”

Chan’s eagerness to learn about watches rubbed off on Fong, and they soon got into studying horology, the art of making clocks and watches.

The duo would watch YouTube videos of watch collectors’ reviews and scour forums on watches every day.

Left to right: Brandon Fong and Wayne Chan.

Left to right: Brandon Fong and Wayne Chan.

Just like Chan, Fong got himself an automatic Seiko watch when he turned 18.

“It was like a rite of passage,” Fong said.

Fong also saved up for his first mechanical watch, one recommended to him by Chan.

The Seiko SKX009J was a diving watch manufactured in Japan.

And as he began to describe his watch, it sounded like he was quoting directly from an advertisement.

“Running it is the automatic movement 7S26... a robust and well-regarded movement that has stood the test of time.”

From my conversation with them, it was clear they knew a lot about the intricacies of their watches. This made them appreciate their watches beyond a monetary value.

A “timeless” possession

As a full-time student with a year to go before he graduates, Chan doesn’t seem to be in the ideal financial position to spend thousands on watches at the moment — unlike other watch collectors who are older and better-positioned to finance their hobby.

But Chan’s scrimping and saving — like he did over two and a half years for his Rolex watch — is for the sake of buying items he believes will stick with him for a long time.

Chan’s Omega watch.

Chan’s Omega watch.

The “permanence” of a well-made watch was something Chan marvels at.

Watches, at least to collectors, are timeless objects.

“I really like the idea that I can buy a watch at the age of 21 and still be wearing it at the age of 60,” Chan said.

Unlike electronics and clothes that we expect to eventually throw away, a mechanical watch that’s cared for can last a lifetime and even over multiple generations. This was the value Chan saw in them.

Watchmaker Patek Philippe’s 1996 advertising campaign promoted the same idea with the classic slogan: “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation.”

But there’s no denying that with their high price tags and a healthy resale market, they do function as investment pieces.

The price of a Patek Philippe Nautilus 5711A, which sells for about US$35,000 (S$48,320) at retail, surged to US$240,000 (S$331,334) in the first quarter of 2022.

It also has been observed that the price for watches like the Girard-Perregaux Laureato, Cartier, Breitling, and nearly all models from the Omega Speedmaster collection has increased in value.

It can be lucrative to buy a watch and resell it at a higher price, but many watch collectors don’t buy watches with the intention of reselling them.

For Chan and Fong, they see watches as accessories they want to wear, not something to keep away. Chan said:

“For people who buy watches as investments, they usually don't wear them. They will keep it in a safe. I try to buy watches that I know I will wear.”

An experienced watch collector in Singapore, who requested to remain anonymous, told Mothership that looking at a watch as an investment can “blur the passion and can cloud judgement” of what a watch has to offer.

The collector, who has been involved in watch collecting for the past 10 years said understanding and appreciating the horology of a watch is what’s valuable.

This is very much Chan and Fong’s mindset.

But as we saw in March this year with the Omega x Swatch collaboration social media and speculators can influence the demand for models of a few specific brands.

With some trying to resell watches for a profit, valuing them at nearly 50 times more.

An Augustman writer wryly observed that anyone who thinks the watch is comparable to the well-known Omega Speedmaster is “seriously deluded”.

Looking at the current Omega x Swatch watch listings on Carousel now, most of them are priced from S$350 to close to S$700, nowhere close to how inflated the prices were back in March.

Compared to a much pricier Omega Speedmaster collection that goes from S$8,000 to over S$50,000 at retail stores, an amount Chan and Fong are not able or willing to fork out impulsively.

Just for the wealthy?

Wearing a luxury watch is often associated with a certain social status.

Image via Unsplash.

Image via Unsplash.

But, as an article in The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) points out, the idea that a watch reflects one’s position in a social hierarchy is more prevalent in traditional workplaces. Top executives in tech companies are ditching expensive branded accessories and wearing simple jeans and sneakers.

Yet, there’s still something about noticing a luxury watch on someone’s wrist and thinking to yourself: “They must have quite a lot of money to afford a watch like that.”

Bruno Belamich, the co-founder of watchmaker Bell & Ross told Mr Porter, a high-end fashion site, that watch ownership boasts one’s status.

Whether it be how wealthy they are or if they are connected to respected members of the community.

“Personally, it’s the ‘connections’ that make me feel that there’s a perceived exclusivity in the hobby,” Chan said.

He explained that if a watch has a very limited supply or is in high demand, watch salespersons would reserve these watches for their VIP customers, often frequent clients who have already spent a lot.

Simply put, the more you spend, the more they’ll want to work with you.

You could have the money to pay, but if you don’t know the right people, you might just be a number on a long waiting list.

Chan added:

“Suddenly, having the money isn’t enough, you need to be ‘known’ as well. Thankfully this is happening only to a select few watch brands but they’re brands that see huge demand for their watches.”

Chan admitted that he’s envious of those with the right connections or family in the space as it would have made things easier for him.

While price tags can be a barrier to entering the watch collector’s market, the seasoned collector argued that “it doesn’t always have to be”.

Of course, there will always be super high-end items that only a wealthy few can afford.

“But watch collecting and appreciation [goes] beyond luxury brands,” the collector added.

The watches Chan brought to the interview.

The watches Chan brought to the interview.

Take Fong, for instance. With his collection worth under a thousand dollars, he continues to learn about watches and observes what other collectors are looking at. But he plans to stick to a similar watch collection of less pricey watches in the near future.

“I chose Seiko because I feel that they dominate the entry-level market in terms of value. At a price range of about S$300, you can get a mechanical piece from a universally recognised company with a rich history in watchmaking.”

At the end of the day, picking out which watch to add to their collection, is based on what they like about the make, design and even the history of the watch.

Watches mark milestones in their lives

When I asked Fong and Chan what their end goal was, they both said they had never thought of their hobby that way.

From the beginning, the two viewed getting a new watch as a milestone in their lives. It was something they achieved at each stage of their lives, be it a birthday or graduation. Chan added:

“[The watches] serve as a way for you to just record some memories, and then you can look back on them. A reminder of the things you’ve done.”

They do have short-term goals for their watch collections: To research and find their next target watch, or as collectors call it, their “grail watch”. Chan explains:

“In watch collecting, there is the ‘grail watch’, which is a watch that you really want, save up for and buy…. It can be any watch, but it's something you want to buy, like a goal.”

For Chan, at 21, that was his Rolex Submariner. For Fong, his Seiko watches.

“Even if you’re not ready to buy a watch, [it] doesn’t mean watch appreciation isn’t for you. I promise you that one of the facets of watch appreciation will appeal to you,” said the seasoned watch collector, encouraging those interested in dipping their toes to first read up on different watches and find what they like.

Fong, relatively new to the scene, gave an example of how a watch collector may think a S$15,000 watch is not expensive.

However, if something they weren’t interested in, they would not be willing to fork out the money to purchase it.

It struck me that two collectors at different stages of life said almost the same thing — as the relatively more experienced one said:

“It is only through better understanding that we can properly realise where the value lies… I don't think you need to own a Picasso to talk about whether you like a Picasso or not.”

After my meeting with Chan and Fong, I went back home and watched a couple of videos on how the gears oscillated and how skilled artisans made watches. And I had a newfound respect for their artistry and understood why branded watches had such steep prices.

Would I spend thousands of dollars on a watch right now? Probably not.

But do I understand why someone might? More than I did before.

Top image courtesy of Wayne Chan.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.