PERSPECTIVE: In June 2021, a Singaporean scam victim founded the Global Anti-Scam Organisation (GASO) to help support people around the world who have been affected by cybercrimes.

Part of this work includes rescuing people who have been lured to countries such as Cambodia and Myanmar by false job advertisements and trapped in secretive compounds where they are made to work as scammers.

Mothership spoke to two Singaporeans who volunteer with GASO in its anti-human trafficking department.

They shared how victims are lured over and dragooned into becoming scammers, how the criminal syndicates behind the advertisements and compounds operate, the various challenges faced in carrying out rescue operations, and what Singaporeans need to be aware of.

On Jun. 19, Lianhe Zaobao shared a video detailing the experience of a 26-year-old Malaysian who decided to accept a job offer in Cambodia, only to end up getting forced to work as a scammer for a criminal syndicate.

His ordeal offered a glimpse into the syndicates operating out of the Cambodian city of Sihanoukville and the nature of the scam operations that he was made to run while trapped in one of many such compounds in various Southeast Asian cities.

A person who refuses to engage in scams could face torture

The Malaysian was made to work as an online investment scammer by looking for potential victims on Chinese social media platforms WeChat and QQ.

He attempted to escape the compound several times but failed due to the compound's isolation and armed security.

The compounds are effectively self-contained neighbourhoods with minimarts, living quarters, clinics, restaurants, massage parlours and salons.

The Malaysian also told stories of people who attempted to leave but were beaten and confined upon being discovered by the syndicate.

Speaking to Mothership, a Singaporean who joined GASO's anti-human trafficking department as a volunteer in March 2022, Lucy (not her real name), said these experiences are typical in such compounds, regardless of whether they are located in countries such as Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, the Philippines or Thailand.

Another volunteer, Carol (not her real name), who joined the department in July 2021, said those who refused to be scammers were tortured by the syndicate.

This includes being beaten, starved, locked in a room, having your phone confiscated or being sold off to another syndicate.

Carol also provided photos and videos shared with her by people trapped within compounds in Cambodia.

Carol said these images showed bunk-like living conditions and offices where they must work more than 12 hours to bring in "sales" as a scammer.

Photo courtesy of Carol

Photo courtesy of Carol

Photo courtesy of Carol

Photo courtesy of Carol

According to the accounts of people within these compounds, Carol estimates that working hours there can be up to 14 hours a day.

Those tasked with targeting victims in Asia usually have to work from 10am to midnight, whereas those targeting Europe and the U.S. have to work from 11pm to 12pm the following day.

The scammers are only allowed occasional meal breaks that range from 30 minutes to an hour, Carol pointed out.

In addition, if they cannot meet "sales" targets, they may have to work overtime.

The scammers can also be beaten for their poor performance or a perceived "poor attitude" by the syndicates.

For the scammers, "you never know when they (the syndicates) find fault or when they want to beat you," she highlighted.

On top of that, a debt of tens of thousands of US dollars is usually imposed on the victim by the syndicate — an amount they are required to pay if they want to leave, Carol said.

This is known as the "赔付" or "bondage debt".

Similar stories in regional media

The stories recounted by Lucy and Carol are not unique, nor are they the most harrowing. Escaped victims have shared similar stories of confinement and abuse with regional media.

Most of the victims tricked into working for such syndicates are from China, along with many from Southeast Asian countries.

Both Zaobao and Japanese media Nikkei Asia reported that people tricked into working for such syndicates can be subjected to physical abuse such as being beaten repeatedly with a stick or even being electrocuted with a taser.

According to others who escaped, there are also people who allegedly have been killed, with their deaths reported as suicides afterwards, Nikkei Asia further reported.

On Aug. 19, AFP reported that about 40 Vietnamese people escaped from the Golden Phoenix Entertainment Casino in Cambodia by fighting with the security guards and swimming across the river to reach Vietnam.

At least one person has been reported missing after being swept away in the river.

Vietnamese media VNExpress reported that the workers had been persuaded to work at the casino through either advertisements or acquaintances who promised them "easy jobs and high salaries."However, the workers soon discovered that their role was to trick people into putting their money into online games instead.

If they failed to meet the quotas imposed, they would either be beaten, have their salaries docked, or get sold off to another casino.

One of the victims, who is 20, alleged that they were forced to work 14 hours daily under threat of being beaten to death.

The challenges of rescuing a victim who has been trafficked into a scam compound

The Malaysian in Zaobao's report was eventually rescued after three months, under the coordination of GASO, when he took the risk of being beaten to message his family about his circumstances.

His family filed a report with the Malaysian police and embassy, with the assistance of GASO.

According to Lucy, GASO works with local contacts and organisations on the ground to organise a rescue.

However, such rescues are incredibly challenging to pull off and cannot just be done whenever a call for help is made, she said.

Carrying out an operation involves finding out where the compound is located and the extent of the danger present — such as the ties it has with the local authorities and the syndicate running the compound, Lucy added.

The onus of providing such information is usually on the victims themselves, Lucy pointed out, or the rescuers do not know where to start.

The victims must also avoid getting into more trouble themselves, with GASO generally advising those who call for help to "pretend to be compliant".

"You have to pretend to be compliant regardless of how much you don't want it (having to scam others) and then from there, we find a way to get you out. It's not immediately you know, I'm not David Copperfield."

In some instances, such as within Sihanoukville, it is "virtually impossible" to save a victim from a compound because of the influence that the syndicate has with the authorities, Lucy further said.

Nikkei Asia noted that syndicates in Cambodia are able to purchase the protection of some local authority figures.

The Japanese media outlet further highlighted that in one case, local police officers accompanied the bosses of a syndicate to recapture trafficked workers who had escaped.

Aljazeera also reported that several scam compounds, particularly those located in Sihanoukville, have links to some of the biggest Chinese investors in Cambodia.

In countries such as Myanmar, the political situation makes it extremely difficult to rescue a victim, Lucy said.

The United States Institute of Peace (USIP), an American federal institution that deals with violent conflict around the world, reported in April 2021 that following the military coup in Myanmar, transnational Chinese gangs were able to widen their activities within the country by working with factions within the armed forces and various militia groups.

Many of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) within Myanmar, focused around Chinese-owned casino developments, have since become linked to online scams, human trafficking and sexual exploitation, according to an August 2022 feature by The Diplomat.

Not all pleas for help are genuine

This leads to Lucy's next point about the people trapped within the compounds: they are aware of what they are doing.

GASO's anti-human trafficking department does not rescue people who have been at a compound for three months or more because it generally means such "victims" are willing participants in the scams.

If such profiles call for help, according to Carol, it is because they are incompetent at "doing sales" — that is, scamming people.

Lucy added, "Anybody in their right mind, if you do not know what you are being tricked into, will immediately look for help."

Lucy shared a recent case she dealt with — a Hong Konger brought to a scam compound in Myanmar on Aug. 11 after flying over to Thailand on Aug. 10 in response to an advertisement for a job opening.

"He panicked and immediately went to ask his family for help," she said.

In contrast, she added that a call for help from someone who has been at a scam compound for two to three months is "dubious", as it means that this person has probably tried to engage in scamming.

"When we talk to a person who wants to be rescued, we will also roughly know their mindset or their thoughts," she said.

Checks on the person's background will also be carried out. This includes reaching out to their family members to help determine if a person is lying and whether a rescue should be made, Carol further elaborated.

She added that many of the people they talked to wanted to be rescued because they could not do "sales".

Carol acknowledged however, that there is still a minority among this group who really do not want to engage in scams but were doing so under the threat of torture by the compound's management.

How do people even end up there?

This brings up my next question: how do these victims within the compounds even end up in such a position in the first place?

Here, Carol shared another insight she gained from talking to many scammers: many of them are in desperate situations in their home country.

Desperation borne out of debt

According to Carol, many scammers are from mainland China and are either heavily in debt or have a criminal record.

"Basically, they cannot survive in China and they move out," she said.

Compounding this desperation is the fact that many syndicates have lured people through false advertisements promising high salaries for job openings, particularly in Cambodia, mainland Chinese media Global Times and China Daily reported.

Making money through scamming is therefore seen as a means of earning quick money, and a path towards a better life, Carol added.

According to state-run media outlets, the Chinese embassy warned its citizens at least twice in 2022 about such job advertisements.

Elsewhere, in Malaysia and Taiwan, the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic has also caused many to seek jobs online. Some inadvertently come across jobs advertisements by the syndicates, Carol pointed out.

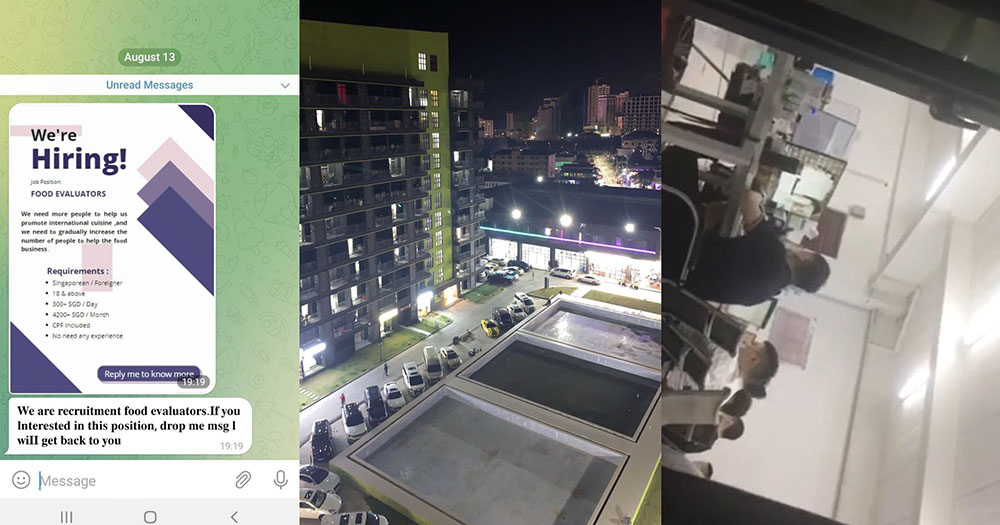

Images shared with Mothership showed such job advertisements calling for "food evaluators", translators and people with tech-related skills.

Photo courtesy of Carol. Job advertisement targeted at Singaporeans.

Photo courtesy of Carol. Job advertisement targeted at Singaporeans.

A fake translation job advertisement requiring "relocation" to Thailand. Photo courtesy of Carol.

A fake translation job advertisement requiring "relocation" to Thailand. Photo courtesy of Carol.

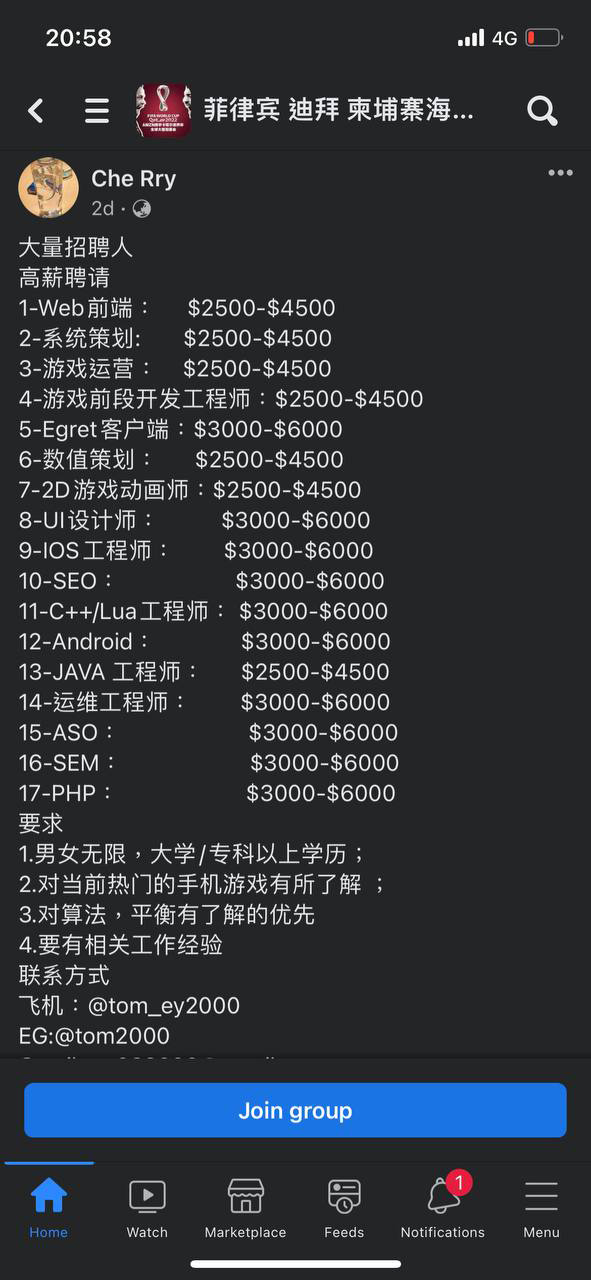

A fake job advertisement calling for people with tech-related skills and promising people with different tiers of pay depending on their specialties. Photo courtesy of Carol.

A fake job advertisement calling for people with tech-related skills and promising people with different tiers of pay depending on their specialties. Photo courtesy of Carol.

On Aug. 9, Taiwan's Central News Agency reported that one of Taipei's City Councillors (elected lawmakers) issued a warning about several Taiwanese being lured by the promise of lucrative jobs to Cambodia, only to be held against their will and forced to engage in illegal work.

The councillor noted that within Taiwan, organisations behind the fraud lured victims by first inviting job applicants to interviews at expensive venues and then persuading them to sign exploitative contracts after gaining their trust.

However, she acknowledged that some victims could also have prior drug or fraud convictions, which means they are less likely to report their experiences to the Taiwanese authorities. This makes it harder for the authorities to take action.

In Malaysia, Bernama reported in July 2022 that 46 Malaysians were rescued from Cambodia after they were reportedly duped by high-paying job offers.

Malaysia's ambassador to Cambodia, Eldeen Husaini Mohd Hashim, issued a statement warning Malaysians to be cautious of job advertisements promising high salaries overseas.

He said, "Check with relevant authorities including the embassy to validate the job offers. Do inform your parents and relatives in Malaysia if you receive such offer. They might give you a valuable second opinion on whether the job offer is a scam."

A Chinese businessman, who is part of a volunteer network in Cambodia that helps to rescue such victims, gave an estimate of at least 30,000 people who have been trafficked into Cambodia, according to Nikkei Asia.

A spokesperson for Cambodia's police has denied that cases are in the thousands but has acknowledged that "some" cases have happened.

Unsuccessful rescues

A victim who was sold off to another scam compound by his rescue driver in Myanmar

Lucy shared that the first case she ever worked on involved a Chinese victim who ended up in a scam compound in Myanmar due to an online job advertisement for work in Thailand.

He flew to Bangkok, where he was met by a snakehead (human trafficker) at the airport, who took him by car to the Thai town of Mae Sot on the border with Myanmar.

The snakehead then smuggled him across to Myanmar by sailing along the Moei River towards a tiny jetty that turned out to be an entrance to a scam compound.

According to Lucy, three to four days after arriving at the compound, he eventually reached out to GASO.

While at the compound, he was tasked with "recruitment" or luring more people over into the compound, she said.

Lucy highlighted that initially, the man would "recruit" people, then ask her to warn them not to come as it is a scam.

Lucy added that as a result of her interactions with him, she also gained more insights into how the recruitment process worked.

However, once the syndicate boss began checking his communications daily, he could no longer provide such information, resulting in at least one person he "recruited" going over to the compound.

He also made multiple attempts to escape, she said.

However, he would be caught and beaten by men guarding the compound each time.

The man eventually turned to asking his family to help pay for his bondage debt, which started at US$10,000 but subsequently ballooned to more than US$30,000.

The rise was due to the costs of the people he "recruited" but backed out at the last minute being added to the debt, Lucy told me.

This included items such as the price of their air tickets, she added.

He was nonetheless able to raise the inflated amount, with the help of his family.

The man also had to pay an additional sum of almost US$10,000 for a driver who would take him out of the compound.

However, upon leaving the compound, the driver took him to another compound instead, 10 minutes away.

"He had been sold by his driver for US$30,000," Lucy said.

What do Singaporeans need to be aware of?

I then ask Carol and Lucy a question even closer to home: have they encountered any Singaporean victims or scammers so far?

Both of them said that they have only heard about the presence of Singaporeans in Cambodian scam compounds from other scammers they have spoken to.

They have also not personally encountered any Singaporean victims seeking help.

Mothership has reached out to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for more information on the matter.

When I asked what Singaporeans need to be aware of, Carol told me that it is crucial for Singaporeans to first be aware of the scam industry.

"A lot of Singaporeans don't know about what is going on in the 'dark world'," she said.

"Singaporeans are very sheltered and innocent to a certain extent. It is very easy to get into trouble, really," Lucy pointed out.

There is also the fact that these scammers can be encountered in person in popular holiday hotspots, such as in clubs in Thailand, and can come off as being friendly and approachable.

Such people will strike up conversations with you, said Carol, relating one of her own experiences at a club in Bangkok.

In her case, Carol said that red flags were raised once the person she talked to mentioned that his job involved cryptocurrency and repeatedly asked her to stay with his friends in Thailand for a few more days to spend time together.

Similarly, Lucy shared a story of a Chinese national who claimed that he was kidnapped and sold off to a compound in Myanmar, having been lured by an invitation from an acquaintance and fellow countryman at a club in Thailand, who invited him over to the Thai border city of Mae Sot.

Calling on Singaporeans to be more careful, they said, "Stick to yourself and your friends, don't kay kiang (act smart) and join others, even if they seem 'normal' or 'friendly'."

Top images courtesy of Carol

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.