Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

On the evening of Aug. 21, 2022, the who’s who of Singapore’s LGBTQ+ activist scene gathered at The Projector X Riverside for a watch party of the National Day Rally (NDR) speech.

In the months and weeks preceding Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s annual address, there had been rumours and whispers that the government was getting ready to repeal section 377A of the Penal Code, a law that criminalised homosexual intimacy in Singapore.

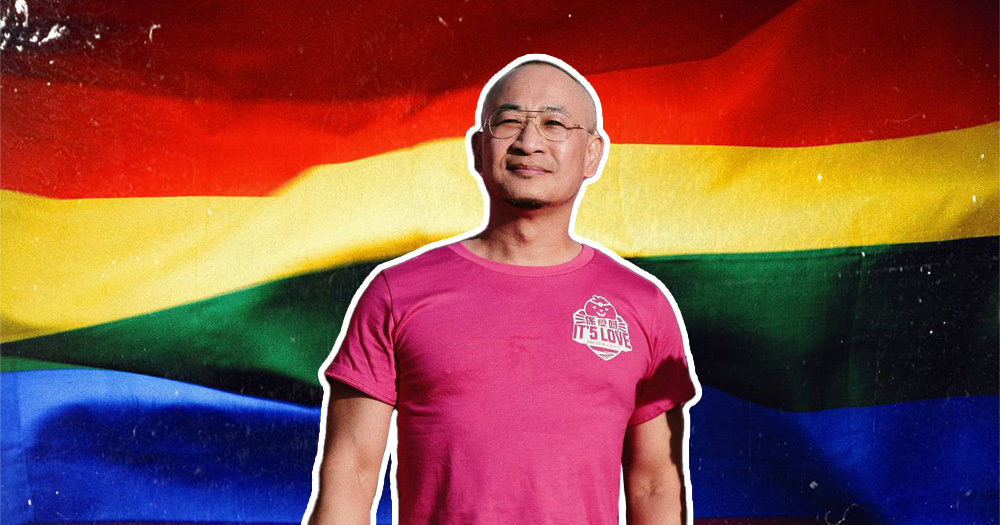

Among those at The Projector was Alan Seah, a 59-year-old gay man who had spent the last 15 years campaigning for the 50-word sentence to be consigned to the history books.

His most recent contribution had been as a founding member of Pink Dot, a yearly LGBTQ+ event held at Hong Lim Park.

From its inception in 2009 till today, Seah has remained a member of the organising committee for what is the only large-scale LGBTQ+ rally in Singapore.

But Seah’s advocacy precedes even Pink Dot — he was one of the organisers of a 2007 open letter to PM Lee, urging the government to repeal the anti-gay statute.

In many ways, that letter, which garnered more than 8,000 signatures, along with a parliamentary petition that was submitted concurrently, kicked started the national conversation on 377A.

Fast forward 15 years, and PM Lee, speaking live to the nation, tackled the issue head-on once more.

“It is timely to ask ourselves again the fundamental question: should sex between men in private be a criminal offence?” he said.

He noted that most Singaporeans did not think homosexuality should be criminalised, that the law had been the subject of numerous challenges in the court and could foreesably be struck down in a future ruling.

“For these reasons,” PM Lee said, “the Government will repeal Section 377A and decriminalise sex between men.”

“I believe this is the right thing to do, and something that most Singaporeans will now accept.”

A video taken by filmmaker Boo Junfeng captured the moment those words fell on the ears of those at The Projector.

In the middle of the cheering, screaming, flag weaving, and general merrymaking, was Seah.

He had risen to his feet in applause with an expression that could be described as stoic satisfaction.

Seah had been involved right at the very beginning of Singapore’s public grappling with 377A, and was now witnessing the closing of that chapter.

"Relief," said Seah when I asked him how he'd felt in that moment.

"Relief that finally we will be rid of this huge obstacle."

Kicking up a fuss

Seah traces the roots of his activist-tendencies to his time in junior college in 1980, when as a student failing Chinese, the school had effectively expelled him.

The government had just introduced a new policy to promote bilingualism; it made passing a second language a pre-university requirement and Seah was part of the first cohort that it applied.

“Very suay, I kenna that first year,” he told me.

Having been born in an English-speaking household — neither Seah’s mother nor father could converse in Chinese — he struggled in picking up a second language while generally excelling in all other areas of his studies. He had failed his O-Level Chinese exams but gotten into a junior college anyways.

“I went to Catholic Junior College (CJC), but we were required to take our O-Level (Chinese examinations) again at the end of the year. They hoped that we would pass and that we would be able to stay and graduate the next year with our A-Levels.”

“True to form, I failed again,” Seah said smiling.

It turned out that Seah was one of 90 students across Singapore whose second language exams scores did not meet requirements and whom the Ministry of Education was offering one last chance to complete the A-Levels, though this time at an institution where the load would be spread over three years instead of two.

Yet, that prospect wasn’t very appealing to a 17-year-old Seah. He along with 28 other students petitioned the government to allow them to stay at their schools.

Though ultimately unsuccessful, Seah’s recalled his first campaign with an understandable tinge of sentimentality.

“We organised ourselves. We wrote letters to the press — to the forum page. We were interviewed by the TV channels,” he said. “And we really kicked up a fuss.”

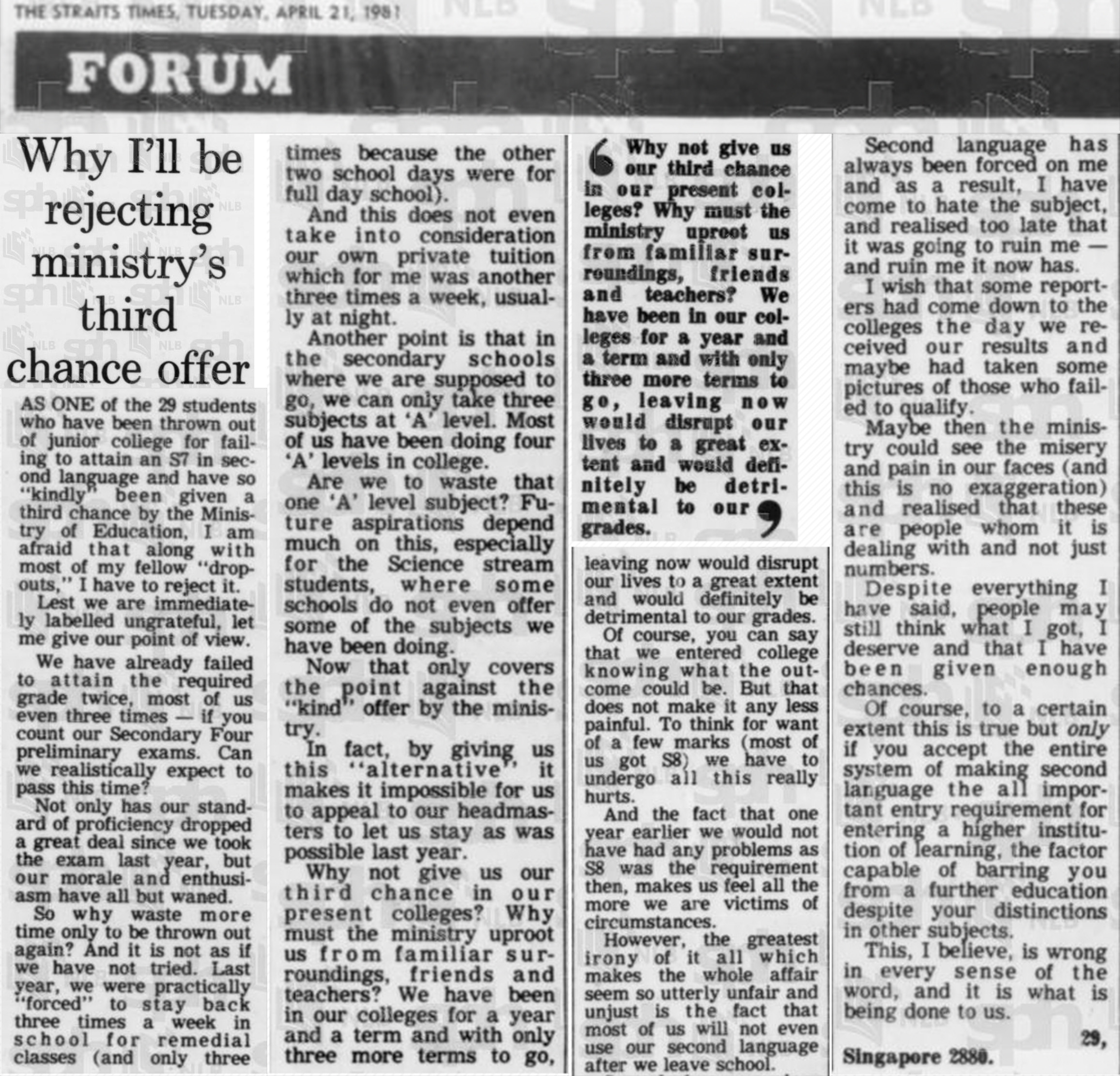

One of the letters written by students who had failed their second language requirement. Image from NewspaperSG

One of the letters written by students who had failed their second language requirement. Image from NewspaperSG

A big part of why Seah was so determined to stay at CJC was the friends he had made during his one year there.

They were the first people he’d come out to in his life, an experience he described as “cathartic”.

“I came out to one of them, and it felt so amazing that I came out to all of them,” he said.

“It’s just such a weight off your shoulders. It’s like ‘wow’, you know? It’s night and day, it’s like being able to breathe rather than suffocating.

We remain the best of friends till today… I always tell them, ‘I’m so lucky to have had you guys and to have come out to you guys first in such an accepting environment.’”

Seah was quick to acknowledge his relatively privileged circumstances; not everyone’s coming out is met with similar support. Yet, such acceptance, Seah mused, played a large part in helping his 17-year-old self resolve many of the internal debates he was having.

“I think that really helped me become the person that I am,” he said.

The 2000s, a rollercoaster for the gay community

Seah did eventually make it through pre-university (via private education), before continuing his studies in the U.S., where he also started his career in advertising.

He returned to Singapore in 1996 and would go on to be a prominent member of the local gay community, opening the gay club Happy with film and theatre director Glen Goei in 2004.

The 2000s, it would turn out, was a pivotal decade for Singapore when it came to LGBTQ+ rights.

In 2003, then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, had given an interview to Time magazine where he revealed that the civil service no longer discriminated against homosexuals in its hiring policies.

"In the past, if we know you're gay, we would not employ you, but we just changed this quietly,” he said.

Goh reiterated his stance at his NDR speech that year — “In every society, there are gay people. We should accept those in our midst as fellow human beings, and as fellow Singaporeans.” — before ominously warning that if the gay community were to lobby for more public space, it could provoke a backlash from the “conservative mainstream”.

“Their public space may then be reduced,” he added.

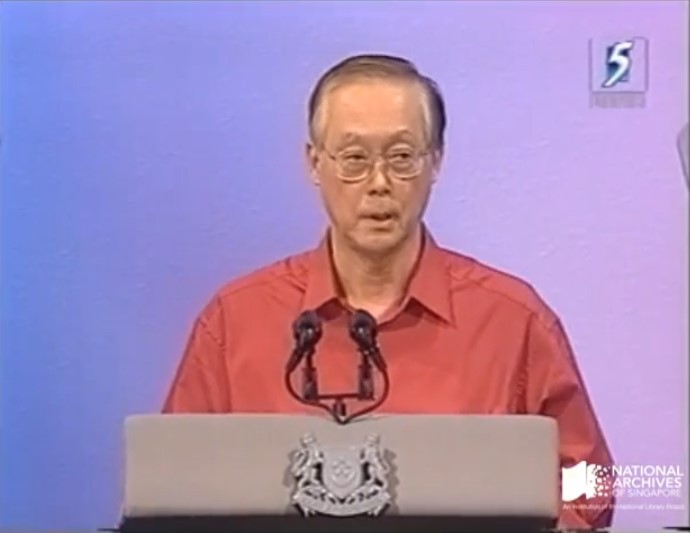

Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong during his NDR speech in 2003. Image from the National Archives Singapore.

Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong during his NDR speech in 2003. Image from the National Archives Singapore.

Despite the foreboding remark, Goh’s public comments sparked a sense of hope within the gay community.

An Aug. 20, 2003 article in Today headlined “An Easier Time for the Gays”, opened with the declaration that “the past two months have been the most momentous for the gay community in Singapore”.

Seah himself penned an op-ed for gay Asian media outlet Fridae, in which he speculated on what Goh’s statement might mean for homosexuals.

“Call me a hopeless optimist,” he wrote, “but I see the whole affair as a breath of fresh air.”

“Implicit in Prime Minister Goh's message are a few uncannily enlightened statements that give cause for enthusiasm: that our government is preparing society for a certain positive evolution in mindset towards gay men and women; that they understand that being gay is not a 'perversion' or a 'lifestyle' but very likely a biological phenomenon; and finally (and very hopefully) that gay men and women will one day be equal citizens in Singapore.”

"Contrary to public interests"

However, by 2005, the collective mood had shifted.

Police had denied a licence for organisers to hold a gay Christmas party called SnowBall, which in effect spelt the end of the Nation parties, a big gay rave that had been held at Sentosa around National Day every year since 2001.

According to Today, police explained that they had been assured by the organisers — Jungle Media, a subsidiary of Fridae — that events like SnowBall and Nation would not be gay parties.

They cited the “openly gay acts”, such as individuals of the same gender “kissing and intimately touching each other”, seen at the parties as provoking several complaints.

Jungle Media’s application to hold SnowBall was thus rejected on the grounds that it was “contrary to public interests”.

Adding to the indignation many gays felt about the cancellation of the parties, was the insinuation by then-Senior Minister of State for Health Balaji Sadasivan that the Nation rave at Sentosa had caused the sharp rise in the amount of AIDS patients in Singapore. (The late Balaji would go on to be a strong proponent of AIDS education programmes and upon his death was hailed by Fridae as a “friend to Singapore’s gay community”.)

Referencing Balaji’s comments, Seah wrote a letter published in The Straits Times Forum section on Mar. 12, 2005, arguing that the battle against AIDS would be better off without the demonisation of homosexuality.

“If education is the key what is stopping us from embarking on an all-out educational drive? It is clear that the authorities are having major problems engaging the gay community,” wrote Seah.

“One major reason is that homosexual acts are against the law here.

We need to admit that we have faltered in our fight against this disease and that one of the major reasons is that we have problems discussing sex and sexuality openly and honestly.”

Section 377A and the review of the Penal Code

Two years later, Singaporeans were indeed discussing sex and sexuality more openly, as the Government proposed amendments to the Penal Code after a review set in motion by the conviction of a police coast guard officer under Section 377 for having oral sex — albeit consensual — with a teenage girl.

In the September 2007 sitting of Parliament, the reading of the Penal Code (Amendment) Bill revealed that while the Government intended to repeal Section 377 — which threatened anyone who engaged in “carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal,” with imprisonment for life — Section 377A would be retained.

The latter was a clause that stated:

“Any male person who, in public or private, commits, or abets the commission of, or procures or attempts to procure the commission by any male person of, any act of gross indecency with another male person, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years.”

It was a crushing blow for those hoping that the review would see the decriminalisation of gay sex in Singapore.

“I think the injustice was felt very palpably,” Seah remembered.

“I don’t think you ever plan to be an activist. I mean I never planned to be an activist,” Seah said to me while describing how he became one of the key driving forces behind the campaign to repeal 377A.

A favoured retelling of how it happened — involving a chance meeting with British actor Sir Ian McKellen — was featured in episode three of AWARE’s celebrated podcast, "Saga".

According to the Sydney Morning Herald, McKellen had been in Singapore in July 2007 as part of the Royal Shakespeare Company's world tour; he was performing in William Shakespeare's "King Lear" and Anton Chekhov's "The Seagull", both staged at the Esplanade.

During his visit, McKellen made use of his media appearances to advocate for Singapore to decriminalise gay sex. This included a hilariously awkward interaction on CNA’s morning show where the celebrated British thespian was asked what he would be doing while in the country during his free time.

“I’m a gay man and I gather that’s not a very popular thing to be, although maybe the laws are about to change and I do hope they do change quickly,” replied McKellen.

“But I’ll be looking for a gay bar, if there is such a thing.”

Seah had gotten to meet McKellen while he was in Singapore and taken by the actor’s humour and mischievous style of activism, asked for his thoughts on the situation in Singapore.

“He was incredibly inspiring,” Seah said on AWARE’s podcast.

“Basically [what he told us was]: ‘Don’t just accept things for what they are’. It wasn’t the only thing that inspired us, but it happened right before [the government announced it would retain 377A] and we were like ‘you know, let’s just do this. Let’s just start this website. Let’s see what happens.’”

The campaign to repeal

Initially started by Seah and his friends as a repository of information on the anti-gay law, Repeal377A.com soon became an online hub where like-minded individuals passionate about LGBTQ+ rights connected.

“There was no big meeting to say: ‘let’s organise something’. It was just because the website was there, the people that were doing things all sort of came together,” Seah said.

“There was no blueprint, no big scheme to do things, other than something needed to be done, so what should we do?”

Separately, work was already underway on a parliamentary petition that was fronted by lawyer George Hwang, former AWARE President Tan Joo Hymn, and Fridae’s founder Stuart Koe. It would be delivered to Parliament by for its members to consider in their debates over 377A by nominated member of Parliament (NMP) Siew Kum Hong.

“I think the feeling was we also wanted something more grassroots, more ground up,” said Seah.

“So how about an open letter to the Prime Minister?”

Coalescing around a campaign to give voice to those who would be affected by the retention of 377A and their allies, a team was formed including Goei — who had given his name to register the website — Johnson Ong, Leigh Pasqual, Pam Oei, Edgar Tang, Tan Chong Kee, Sylvia Tan, Choo Lip Sin, and Seah.

(L-R) George Hwang, Alan Seah, Siew Kum Hong, Leigh Pasqual, Pamela Oei, and Johnson Ong after PM Lee's National Day Rally in 2022.

(L-R) George Hwang, Alan Seah, Siew Kum Hong, Leigh Pasqual, Pamela Oei, and Johnson Ong after PM Lee's National Day Rally in 2022.

Seah and Chong Kee co-wrote the letter before the team took to the streets of Singapore to canvas for support.

“Those were hard-won signatures,” said Seah, recalling how one of the places they would visit were clubs — “including anywhere that was slightly gay-friendly, where we wouldn’t get kicked out”. They would also put out calls for people to visit certain locations where organisers were on hand to facilitate the petition signing.

The result of that campaign were 8,120 signatures, collated in a large grey folder.

“We had no idea [how to deliver a petition],” Seah said, chuckling.

“I remember calling the Istana and the Prime Minister’s office to say ‘hey I’ve got this petition. Is there any way I can deliver it to the Prime Minister?’”

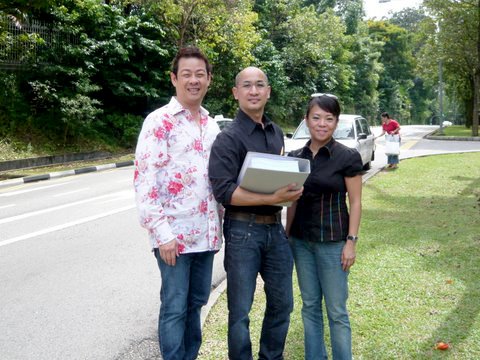

After enduring a couple of ‘huhs’ and a chain of being put on hold and transferred from one civil servant to the next, Seah was eventually told he could bring the open letter to the guard house at the rear entrance of the Istana. He would do so on Oct. 23, 2007, with Oei and theatre actor-director Ivan Heng along for the ride.

“[I was] a bit nervous. I didn’t think we’d be arrested. I mean there was nothing to be arrested for. But the heart was definitely beating fast.”

In the end, it was rather anti-climactic. The trio walked up to the guard house, explained why they were there to the perplexed guards, and handed over the folder.

A policeman doing his rounds was asked if he’d mind taking a photo of Seah, Oei, and Heng. Along with a photo of Seah and Oei, it remains the only piece of visual memorabilia from the delivery of the petition.

(L-R) Ivan Heng, Alan Seah, and Pamela Oei deliver the open letter to the Istana. Image courtesy of Alan Seah.

(L-R) Ivan Heng, Alan Seah, and Pamela Oei deliver the open letter to the Istana. Image courtesy of Alan Seah.

Thankfully, despite the confusion of the guards receiving it, the open letter did eventually reach the desk of PM Lee and he acknowledged it at his speech in the October sitting of Parliament.

377A was the hot-button topic of that sitting, prompting 17 members of parliament to speak on the issue, including impassioned speeches from Siew and fellow NMP Thio Li-Ann, for and against the repeal respectively.

Thio’s speech, in particular, has since gained notoriety amongst LGBTQ+ activists for her graphic portrayal of gay sex — at one point she likened it to “shoving a straw up your nose to drink” before going on to describe the act of rimming.

The National University of Singapore law professor also made references to the idea that preserving 377A would serve as a bulwark against the future legalisation of same-sex marriage and child adoption rights.

Doing both, argued Thio, “subverts both marriage and family, which are institutions homosexuals seek to redefine beyond recognition”.

LGBTQ+ and the family

Such rhetoric about protecting families from the influence of homosexuals has persisted till today, though for Seah there isn’t a more nonsensical argument to make.

“Singapore's always been a diverse country — different races, different religions. And we’re proud of the fact that we generally get along. I think for the LGBTQ community we want to be part of that fabric,” Seah explained.

“When people talk about the family vs. LGBTQ, that doesn’t make any sense because LGBTQ people come from these families. Would you rather a family is split up because there's no acceptance? Because they feel they have to kick their LGBTQ child out?”

Seah pointed to his own parents and their acceptance of his sexuality as an example of how the concept of a tight loving family and homosexuality need not be viewed as incompatible.

Two interactions stood out for the 59-year-old.

The first was when he wrote the forum letter in 2005, arguing that Singapore needed to be more open to homosexuality if it were to successfully deal with the spread of AIDS.

“I remember my father called me up and said, ‘I saw your letter today…’ and I was waiting to hear what he was going to say. And he just said, ‘well done’.”

The other occurred when in 2007, Seah asked his mother, a Catholic, if she would sign the open letter on 377A.

“She read the letter, and I said, ‘will you sign?’ and she said ‘yeah sure’. So I was really curious what she would write.”

Next to her signature, Seah’s mother had written: “God made all of us, so what’s the fuss?”

While Parliament eventually voted in favour of the Government’s proposed amendments to the Penal Code, leaving 377A intact with the assurance that it would not be enforced, Seah was not disheartened.

“You can’t be an activist without being an optimist, otherwise you wouldn’t do it. Hope is always there but I don’t think we were super hopeful that it would be repealed, but it achieved a lot of things.”

One of those things was the formation of a small energised community of Singaporeans, ready to continue the campaign to see 377A repealed.

“It felt like the gay community had finally come out of the closet in Singapore,” Seah said.

Painting Hong Lim Park pink

Another opportunity to channel that optimism would arrive in 2008 when the Government moved to loosen the rules surrounding outdoor demonstrations at Hong Lim Park.

Announcing the decision at his NDR speech for that year, PM Lee said:

“I think we will still call it Speakers’ Corner, no need to call it demonstrators corner but we will manage with a light touch. So I think there is no need for the police to get involved.”

A little more than a week later, police, the Ministry of Home Affairs, and the National Parks Board (NParks) held a joint press conference to furnish more details on the handover of Hong Lim Park from the purview of the police to NParks.

“Burn an effigy of a Singapore political leader? Or organise a gay pride event outdoors? From next week, protests like this will have a place in Singapore,” read a line on the front page of Today.

For LGBTQ+ activists the second clause must have read like a challenge.

In 2009, the first ever Pink Dot was held at Hong Lim Park, taking advantage of the new rules.

Seah, who by this point must have begun to appear like the Forrest Gump of Singapore’s pro-gay movement, was part of the event’s first organising committee.

“We had no idea if anyone would show up,” said Seah.

Despite the relaxation of rules, organisers were still wary that Singaporeans might be fearful of attending a protest. There was also the fact that attending a gay pride event, held not at night in the privacy of a gay club but in broad daylight, would constitute a coming out of sorts for attendees.

Estimates for how many people attended the first Pink Dot vary: The New Paper reported 500 attendees, The Straits Times put it at 1,000 people, while Today wrote that nearly 2,500 had gathered at Hong Lim Park.

Nevertheless, Seah remembered feeling heartened by the response.

(L-R) Alan Seah's husband Laurindo Garcia, his mother, and Seah at the Pink Dot photo booth. Image by Steven David Lim Photography. Courtesy of Alan Seah.

(L-R) Alan Seah's husband Laurindo Garcia, his mother, and Seah at the Pink Dot photo booth. Image by Steven David Lim Photography. Courtesy of Alan Seah.

The annual event has only grown in scale ever since; today it is undoubtedly the most important date of the year for the LGBTQ+ community.

And while many organising committee members have come and gone, Seah is among three or four who have served every year since the inaugural Pink Dot.

This year’s rally saw thousands flock back to Hong Lim Park following two years where the pandemic derailed plans for large-scale physical gatherings.

But it was one attendee that caught the eye — dressed in a light pink polo shirt and white slacks, Henry Kwek, a lawmaker from the ruling People’s Action Party, became the first member of parliament to attend the event.

Alan Seah and Henry Kwek at Pink Dot 2022. Image by Ching S. Sia. Courtesy of Alan Seah

Alan Seah and Henry Kwek at Pink Dot 2022. Image by Ching S. Sia. Courtesy of Alan Seah

It was the clearest sign yet that change was in the air.

"It's not a good deal"

The reaction to PM Lee’s announcements on Aug. 21, 2022, from the LGBTQ+ community, has been mixed, to say the least.

While some were buoyed by the decision to repeal 377A, the Government’s signal that it would move to safeguard the traditional definition of marriage has left others frustrated.

Daniel (not his real name), a 30-year-old gay Singaporean, told me he couldn’t help but feel that the whole situation was a net loss.

“All the fine print was quite concerning,” he said.

“I mean yes, we can celebrate now that it is like a first step towards something, but for younger Singaporeans like me, millennials or Gen Z’s, it's concerning because we still have years ahead of us.”

For Daniel, a real feeling of being unequal persists because of the way that Singapore has tied many of its policies to the family unit — only married couples, for example, can apply to get a built-to-order flat. Single individuals must wait until the age of 35, and even then are restricted in terms of the size of the unit they may purchase.

Getting equal access to such policies continues to be of greater importance to Daniel than the removal of what he viewed as a toothless statute.

“I mean, yeah sure now we’re not criminals, but we still can’t buy a house, we still can’t get married,” he explained.

"It’s not a good deal, if you think about it. We still have to service the nation and pay taxes.”

Nabil Khairul Anwar, 28 and also gay, told me that he was similarly despondent when he first heard all the news from NDR 2022.

But having had a few days to digest the information, he’s now more appreciative of the clarity.

“In principle, it does matter to me,” he said on the repeal of 377A.

“It also sets the tone as the backdrop for the rationale with regard to a lot of public policy as well.”

When it comes to the rhetoric surrounding the need to safeguard marriage, Nabil said he found it “problematic”.

“The way it's being pushed is like it's a zero-sum game. If you were to repeal 377A, suddenly you are going to endanger families? And you going are going to endanger the sanctity of marriage? Even the term sanctity of marriage — what does that even mean?”

Ultimately, Nabil said that, at least for him, the argument about marriage is one about semantics.

“If they want to have marriage, they can keep it. Then let's come up with a different word, a civil union?

I feel like the underlying thing about this is that marriage is not just a social institution. It’s also a thing that grants you legal privileges. And so to deny people the ability to have some legal privileges, it's almost like structural violence.”

The linchpin

When I posed the frustrations that some younger members of the gay community had with the repeal and the “fine print” it came with to Seah, he was characteristically optimistic.

“They’re absolutely justified, don’t get me wrong, they should be. But channel that anger, that concern, productively,” he advised.

“I think it's great if this energises young people, but I really don’t think marriage is the most important thing right now. But if this energises people to campaign for some sort of protection from workplace discrimination, for fairer housing policies for our community, for education, it will be a great thing.”

Though Seah is far from retiring from activism, we may one day look back at 2022 as the year that a baton was passed from one generation of LGBTQ+ activists to another.

For Seah’s cohort of agitators, repealing 377A was a rallying point, a finish line they could set their sights on. Or in Seah’s words “a linchpin to a lot of other trickle-down effects”.

Neither Daniel nor Nabil begrudge the activists who are celebrating the repeal and championing it as a victory for the community.

“It’s their moment,” said Daniel. “They have fought so hard for 15 years. So I'll say they should enjoy this moment.”

That young LGBTQ+ Singaporeans can now dream of a future where marriage might just be possible, is in no small part thanks to the work put in by activists like Seah, who’s quick to point out that he too had built on the work and toil of preceding activism.

The night before

The night before NDR, Seah was hit with a gamut of emotions.

It dawned on him that all the effort he'd painstakingly sowed for the past one and half decades was about to be validated.

Yet, he could stop ruminating about those who came before him.

"I was just really thinking about all the pain, all the suffering that 377A had caused to the community," he said.

"I thought of all the times we were humiliated in the bars and nightclubs we frequented when the police raided them. I thought about those men who were entrapped in Tanjung Rhu, who had their names and faces splashed all over the newspaper and pretty much had their lives ruined. Then I thought back to all the Singaporeans I know, who have left Singapore and their families to have a decent shot at a normal life.

And the saddest of course was those who might have taken their own lives because Singapore became too much for them."

Each of those moments represented a black mark in Singapore's history, where our diverse society had let the differences between communities get the better of its guiding principles of justice and equality.

The fact that the colonial-era law responsible for giving weight to much of this was about to meet its end was surreal.

"And that really hit me the night before," Seah said, "thinking about 'Wow, is this going to happen tomorrow?'"

Top image adapted from Pink Dot HK's Facebook page

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.