Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

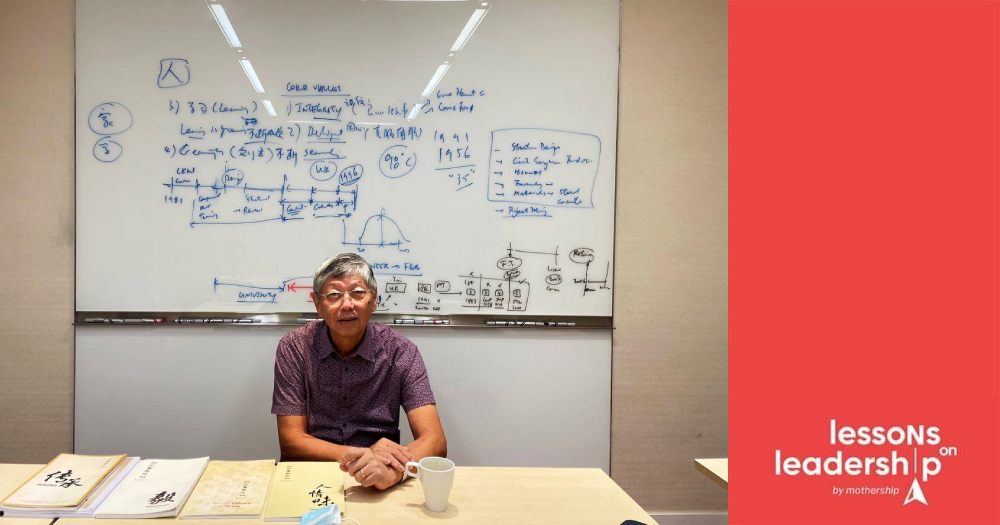

When I first entered the meeting room at the Soup Restaurant HQ, it felt as if I was attending a seminar.

Managing Director (MD) Wong Wei Teck was seated right in front of a whiteboard with a stack of books next to him (I later found out that the books were the company’s annual reports.)

There was also another person seated on the other side of the room with her laptop propped, which further furnished the classroom-like setting.

Was this going to be an actual lesson on leadership?

The 67-year-old Wong kicked off the interview with a series of questions including my Chinese name and the demographic age group of our readers.

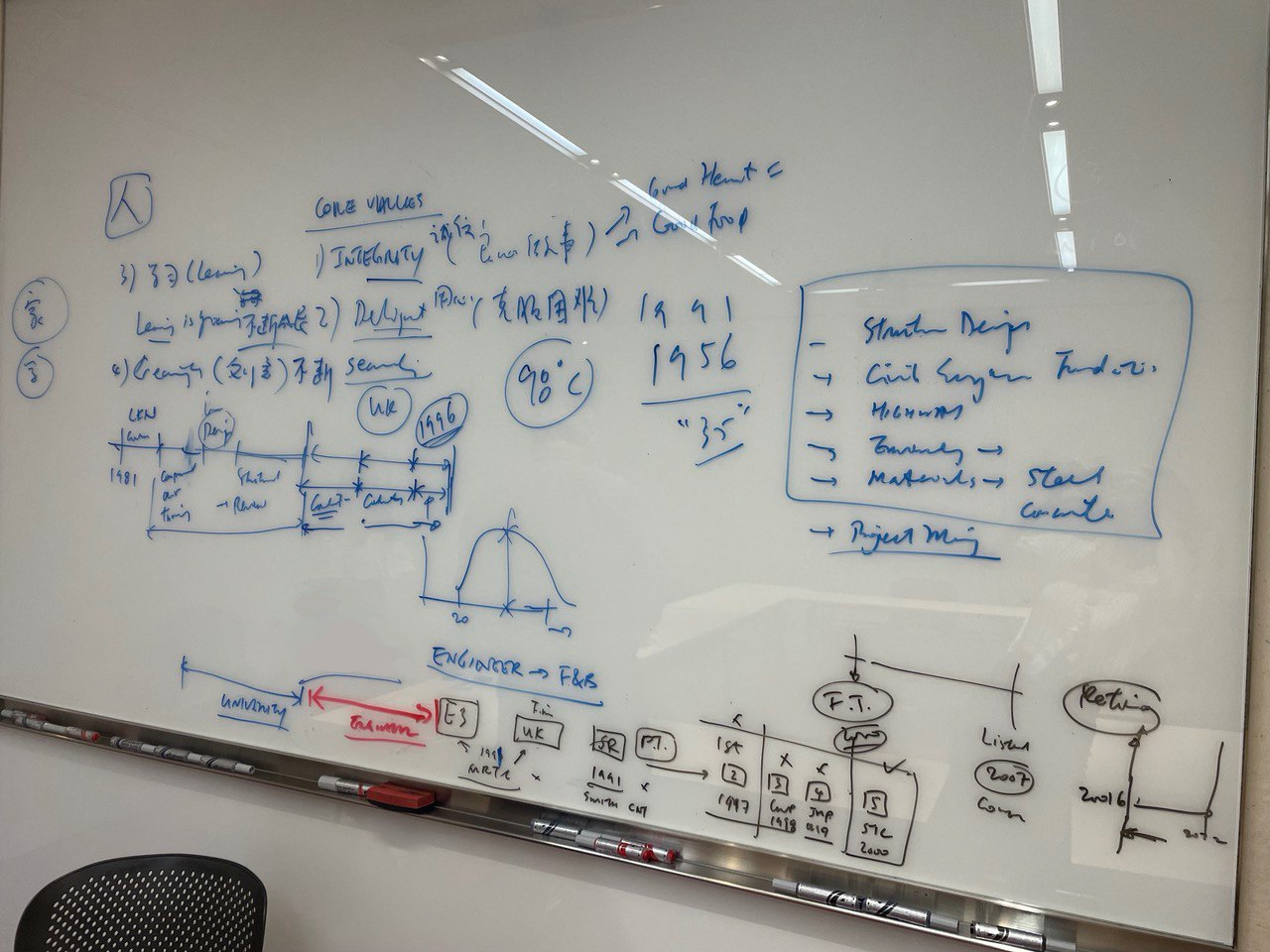

His engineering background came through when he tried to understand it by drawing a graph on the whiteboard.

And then more graphs, including a series of timeline charts that depicted the career changes of himself and his co-founders.

It couldn’t have been more different from what I imagined an interview with a restaurant owner would be.

The whiteboard at the end of the interview. Photo by Karen Lui.

The whiteboard at the end of the interview. Photo by Karen Lui.

Starting out as a “hobby”

Soup Restaurant was founded by Wong and three other co-founders, Mok Yi Peng, Wong Chi Keong, and Mike Ho – all former professional engineers.

All four studied Civil Engineering and used to work at the Mass Rapid Transit Corporation (MRTC), the predecessor of the Land Transport Authority (LTA).

Previously, Wong was mostly in charge of “backend” matters such as IT, HR, and training while Mok managed the operations side of the business.

Wong took over Mok’s duties and role as MD when the latter retired in 2016.

Chi Keong, who shares the same surname as Wong but is not related to him, oversees project and design, including the interior design of the restaurants.

Ho has always been a sleeping partner and remains one to this day, Wong said.

For Wong, Soup Restaurant began with a call.

He had received a phone call from Mok who said that he had rented a space to run a business as a side hobby driven by his passion for food; Mok invited Wong and the other two co-founders to join him.

Wong agreed readily on the spot to start a business with this group of trusted buddies.

Back then, he saw the business as a hobby that could be done on the side without interfering with their day jobs in the engineering industry.

Pooling their money together, the four friends started Soup Restaurant.

The story behind the name

At this stage, perhaps a pertinent question on your mind (as well as the minds of Soup Restaurant fans) is this: What’s behind the restaurant chain’s name?

Its Chinese name “San Zhong Liang Jian” (三盅两件) roughly translates to “three bowls, two pieces”.

As a name for a restaurant, it is not as obvious as its English name, Soup Restaurant. However, it carries a lot of cultural references and nuance.

In Cantonese yum cha teahouse culture, “Yi Zhong Liang Jian” (一盅两件) – which roughly translates to “one bowl, two pieces” – refers to the custom of serving diners two pieces of larger-sized dim sum with their bowl of soup or cup of tea.

You might have come across a zhong, a specific type of crockery that looks like a cross between a bowl and a cup, when you order hot soup or dessert in Chinese restaurants.

An example of a zhong. Photo via Taobao.

An example of a zhong. Photo via Taobao.

According to Wong, Mok came up with the name “San Zhong Liang Jian”.

Playing on the traditional Chinese phrase, “San Zhong” (三盅) refers to the three bowls that came in the set meals that Soup Restaurant used to serve: one bowl of rice, one bowl of dessert, and one bowl of soup.

Each set meal also came with two side dishes. This is the “Liang Jian” (两件) in Soup Restaurant’s Chinese name.

The other two co-founders decided on the English name “Soup Restaurant'', based on Cantonese people’s penchant for soups, which both Wong and Mok had no objections to.

I wish my group discussions were that straightforward.

According to Wong, the four co-founders never had any memorable arguments before the company became listed.

They each played different roles with Mok being the leader back then.

The quartet would discuss important issues among themselves and make decisions based on majority votes, Wong said.

Of course, it’s impossible for partners to agree all the time, he said, but admitted that they didn’t really have the chance to bicker since they were working on the restaurant business on a “part time” basis at that time.

They would “gossip” about each other by lamenting about how a certain partner did things in a certain way, etc. from time to time, Wong conceded, but remain “gentlemanly” when it came to making decisions.

Catapulted from shophouse to mall

Agreeing on matters quickly probably helped expedite the opening of Soup Restaurant’s first outlet along Smith Street in Chinatown in 1991, serving healthy steamed Cantonese meal sets.

Wong was 35 years old then.

Initially when they only had one outlet under their belt, they relied heavily on word-of-mouth to attract potential customers.

And then in October 1991, a food review in The Straits Times catapulted Soup Restaurant into the public’s consciousness.

The reviewer, one Margeret Chan, didn’t exactly rave about the food; she highlighted the “watered-down soups” and inconsistency in execution of the dishes.

Still, she rated Soup Restaurant four out of five stars.

“There is a wonderful aftertaste though, you feel virtuously healthy after you have eaten. Steaming demands very fresh ingredients and the restaurant is most able to honour this requirement because of its proximity to Chinatown wet market."

According to Wong, crowds really started to come in after Chan’s review was published.

It took the quartet six years before they opened their second outlet but the expansion continued steadily thereafter.

They opened more stores in the following order:

- Seah Street in 1997

- Causeway Point in 1998

- Jurong Point in 1999

- Suntec City in 2000

Despite having four outlets under their belt, the four of them were still dabbling in this business as a “part-time” hobby.

It was only in 2000 that they made the decision to leave their day jobs to work on Soup Restaurant full-time, Wong revealed.

In 2007, Soup Restaurant became a listed company.

Today, Soup Restaurant boasts 10 outlets scattered across Singapore, including Paragon, Jewel Changi Airport, and Vivocity.

They’ve also launched three concepts — Teahouse, Cafe O, and Pot Luck — and opened Soup Restaurant outlets in Malaysia and Indonesia.

In the financial year 2020, Soup Restaurant Group recorded S$10.2 million in equity.

A hard lesson

Initially, Soup Restaurant aimed to serve healthy steamed meal sets, which inspired their Chinese name, San Zhong Liang Jian.

Back then, they wanted to cater to the needs of busy working adults who did not have time to prepare their own nutritional Cantonese meals.

“The more we steamed, the more losses we made,” Wong remarked.

They observed and learnt from others in the market in order to improve their business.

When their third outlet was opened at Causeway Point, the team was so overwhelmed by the crowd that one of their chefs literally coughed blood from overwork and had to be hospitalised.

This incident prompted the team to redesign and break down their kitchen processes and workflow.

Looking back, Wong explained to me that they were able to take it easy at their first two outlets because they were located in shophouses and drew a modest crowd.

They learnt the hard way that the same processes did not work at shopping centre outlets which tend to draw larger crowds.

Hearing anecdotes of the co-founders’ hands-on approach to solving issues, I was reminded that all of them – Wong, in particular, are engineers at heart.

An engineer at heart

Wong worked as an engineer – or in his words, a “building doctor” – for 20 years before he started Soup Restaurant with his co-founders.

He investigated issues in buildings and provided solutions for repair and even participated actively by going up on a gondola lift to inspect buildings.

A “building doctor”, said Wong, resolves difficulties instead of viewing them as a hindrance.

“Resolving difficulties itself isn’t a difficulty,” he said, adding that “it’s all part of learning.”

It’s a philosophy that he abides by in other areas of his life.

Despite his status, the former engineer is frugal and down-to-earth, and sees the value in fixing things rather than simply replacing them – like learning to fix his car with the help of YouTube videos and assisting an employee with a tiling issue in her apartment.

Today, even though his main responsibility is to manage the operations of the company, report to shareholders, and look after his employees, Wong still loves engineering deeply, offering free engineering advice in a non-professional setting.

Running an F&B business the engineering way

In a rather profound way, Wong brings the perspective of an engineer to the running of the business.

For instance, having a strong foundation is very important when erecting a building, Wong said. Buildings cannot be built tall without a strong foundation.

Most people cannot see the foundation when they look at tall buildings as it is underground, he noted.

As an engineer, he would spend one-third of the construction time on the foundation before moving on to the rest of the structure.

In the same way, a business needs a strong foundation to succeed.

He cautioned against starting a business based on the assumption that running a business is very easy.

Some people might rush to start a business, enticed by the huge crowds at F&B establishments without building a foundation, he said.

Likening a company’s foundation to the “pillars” in structural engineering – stability, safety, functionality, and economy – Wong explained that a company must be built on the core values of integrity, diligence, learning, and creativity.

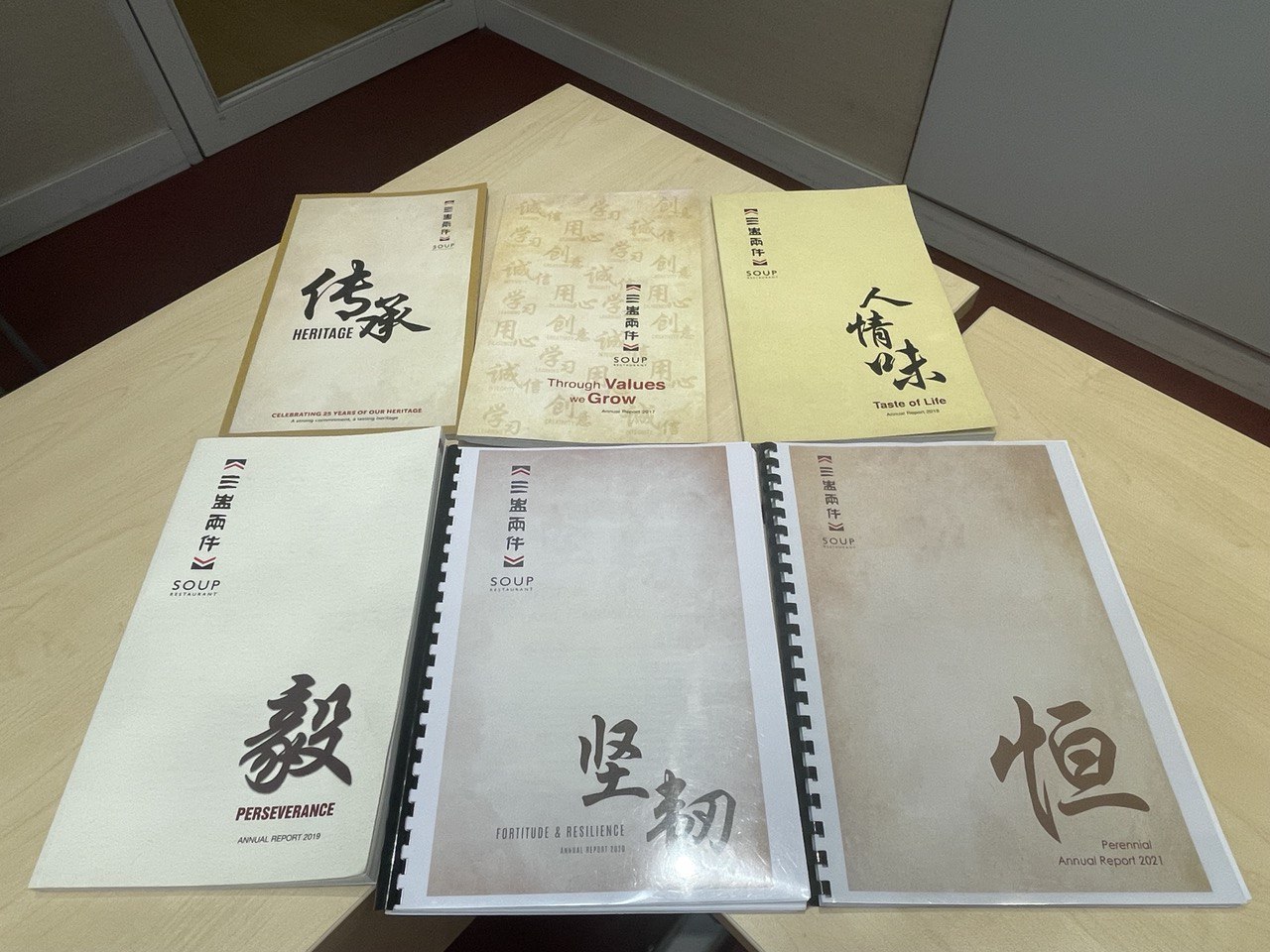

Company’s annual reports with the theme of each year revolving around a specific value. Photo by Karen Lui.

Company’s annual reports with the theme of each year revolving around a specific value. Photo by Karen Lui.

It’s easy for people to brush off such abstract buzzwords that serve as guidelines for the corporate culture.

However, Wong explained how such values have served Soup Restaurant well in the past 30 years.

For example, the business continues to innovate and come up with new items every quarter such as the cute handmade longevity peach buns, Samsui baby buns, and rose buns.

The chain’s latest offering is the panda twin buns.

Photo via Soup Restaurant’s Instagram page.

Photo via Soup Restaurant’s Instagram page.

According to Wong, some qualities that a leader should have are:

- Serve in the team as one of the members

- Earn the respect rather than rely on the power that is associated with the title

- Be unselfish and look after others first before him/herself

- Be magnanimous

A leader also has to differentiate between wisdom and smartness, noting that many people prefer the former over the latter.

He defined being smart as simply having experience while wisdom is the ability to “see the truth”.

“How does one have wisdom? Be calm. When you’re agitated, don’t make decisions. Secondly, no hidden agenda, no office politics. Then, you’ll be able to see the truth. When we make decisions, we usually rely on wisdom.”

Other gems that Wong dropped: The workplace should not be a stressful place; employees are encouraged to be self-motivated and take initiative; don’t put pressure on the employees who put pressure on themselves.

Chicken or the egg ginger sauce?

Perhaps another quality that an F&B business owner should have is love for their product. In Wong’s case, we’re talking about Soup Restaurant’s signature dish, the Samsui Ginger Chicken.

The steamed chicken is served with cucumbers, lettuce, and ginger sauce.

While Wong does not eat the chicken dish everyday, he still has it quite frequently — at least once a week, which includes food audits.

He also always hosts guests with the popular dish, he added.

Wong admitted that he did not expect the chicken dish to become such a hit among customers since they first released it in 1995.

Made with Mok’s family recipe, the dish underwent research and development (R&D), which included plating, deboning, and pairing with lettuce, at Wong’s house.

The original chicken dish was associated with Samsui women in Chinatown who paired it with ginger back in the day.

Would he get bored of eating the dish so often?

Wong paused before replying, “Not if it’s eaten with the ginger sauce.”

That brought us to our next question: Chicken or ginger sauce?

Without missing a beat, he quipped, “Ginger sauce”, because it can be used for other dishes.

The sauce, another popular offering from Soup Restaurant, has also been bottled, making it easy for you to travel with and (attempt to) recreate the dish if you are nowhere near a Soup Restaurant branch.

The sauce has also made its way overseas, released in Japanese supermarkets in September 2021.

Ginger sauce (far right). Photo courtesy of Soup Restaurant.

Ginger sauce (far right). Photo courtesy of Soup Restaurant.

Food for thought

While the Samsui Ginger Chicken is a perennial favourite among diners, Wong revealed that he personally gravitates towards sweeter food on the menu, such as the Coconut Pudding, Sweet and Sour Pork, and Tofu Prawn (that apparently tastes like Chilli Crab).

Steamed Hand-chopped Minced Pork with Salted Fish. Photo by Soup Restaurant.

Steamed Hand-chopped Minced Pork with Salted Fish. Photo by Soup Restaurant.

He also shared that he likes the Steamed Hand-chopped Minced Pork with Salted Fish, which is one of the dishes that his wife does not allow him to indulge in too often.

Apparently, Wong enjoys it so much that he sneakily ate two of them the day before our chat, I learned from a Soup Restaurant employee.

Who would expect the MD of Soup Restaurant to resort to sneaking orders of his favourite dishes at his own restaurant?

Another reason Soup Restaurant is a perennial favourite – its thoughtfulness.

Wong elaborated that Soup Restaurants offers spicy and less/non-spicy versions of the same dish, like the Hometown Fried Fish Belly (with the option to add chilli), the Homemade Tofu (with the option to top with spicy minced pork), and Ginger Fried Rice (option to have less or more ginger).

There’s also the option to debone meat dishes for those who request it.

Such options are great for fussy eaters (like myself) who cannot tolerate spice very well and find it too much work to pick out bones.

If you’ve been to Soup Restaurant, you might be puzzled by why some dishes like Sweet Potato Leaves and Ginger Fried Rice have two variations differentiated by the terms “Ah Por” (阿婆) and “Ah Kon” (阿公).

In Chinese, the terms roughly translate to “grandmother” and “grandfather” respectively but it still didn’t exactly clue me in on the differences between the dishes.

I was told that the “grandfather” option has spicier and stronger flavours whereas the “grandmother” option is lighter.

So, whose grandparents were these conclusions based on?

No one seemed to have a clear answer and it sounded like it was an arbitrary generalisation to make the dishes sound more quirky and family-friendly.

However, the dishes were named by Mok so perhaps his personal experience with grandfathers and grandmothers contributed to this little quirk.

This family-oriented perspective was also reflected in Wong’s quip that unlike other Chinese restaurants in Singapore that pride themselves on their distinctly Chinese cuisine, Soup Restaurant identifies itself as a restaurant serving “home-cooked food” for the family.

“Our dishes follow one principle: 老少咸宜 (suitable for all ages), healthy, traditional, 原汁原味 (original taste and flavour of the food), no frills, very ordinary. Simple dishes, this is what we want. Very 家常 (homely and everyday)."

Why?

“Comfort comes from home-cooked food.”

Lessons on Leadership is a new Mothership series about the inspiring stories of Singapore’s business leaders and entrepreneurs, as well as the lessons and values we can learn from their lived experiences.

Quotes were edited for clarity. Top photo by Karen Lui.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.