Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Dinoflagellates have caught the attention of the nation after being named as the cause of the glowing blue waves at Singapore's western coast over the past week.

These single-cell microorganisms emit a bright, blue glow when disturbed, possibly to confuse predators or to attract other organisms to prey on what's threatening them.

While the presence of dinoflagellates may be new to many of us, some researchers in Singapore have been acquainted with them for quite some time.

Not a plant or bacteria

"It seems like everyone knows the word 'dinoflagellate' already, but not many understand exactly what it is," Clarence Sim told Mothership.

Sim is a second-year PhD student at the Genomics and Ecology of EuKaryotes (GEEK) Lab led by Adriana Lopes dos Santos, an Assistant Professor at Nanyang Technological University's Asian School of the Environment.

"You probably know the different kingdoms of living things -- there's animals, plants, bacteria and fungi," said Sim.

But dinoflagellates belong to a whole other group of diverse organisms known as protists, Sim explained.

Dinoflagellates are common marine plankton well known for having close relationships with other organisms.

Corals for example, have a mutually beneficial relationship with some dinoflagellate species that live in them: they protect the dinoflagellates and provide it with carbon dioxide, so the microorganism can share the nutrients that it makes from photosynthesis with the coral.

While these single-cell microbes might seem unassuming, Sim shared that marine microbes (including photosynthetic dinoflagellates) produce about half of the oxygen we breathe.

In comparison, forests only produce about 28 per cent of Earth's oxygen, according to National Geographic.

A bloom of dinoflagellates observed since January

As part of Sim's thesis, he regularly samples Singapore's coastal waters to map the trends of the local plankton community over the years.

Sim collecting water samples off Singapore's coast. Image via GEEK Lab.

Sim collecting water samples off Singapore's coast. Image via GEEK Lab.

Therefore, the bioluminescent dinoflagellate species responsible for the glowing waves that attracted massive crowds to Changi Beach was nothing new to Sim.

Sim told Mothership that he had detected low amounts of the species over the past two years and identifed the species as Noctiluca scintillans.

Then in January, he observed a bloom of Noctiluca scintillans, but noticed something peculiar about them this time.

Hosts thousands of tiny algae

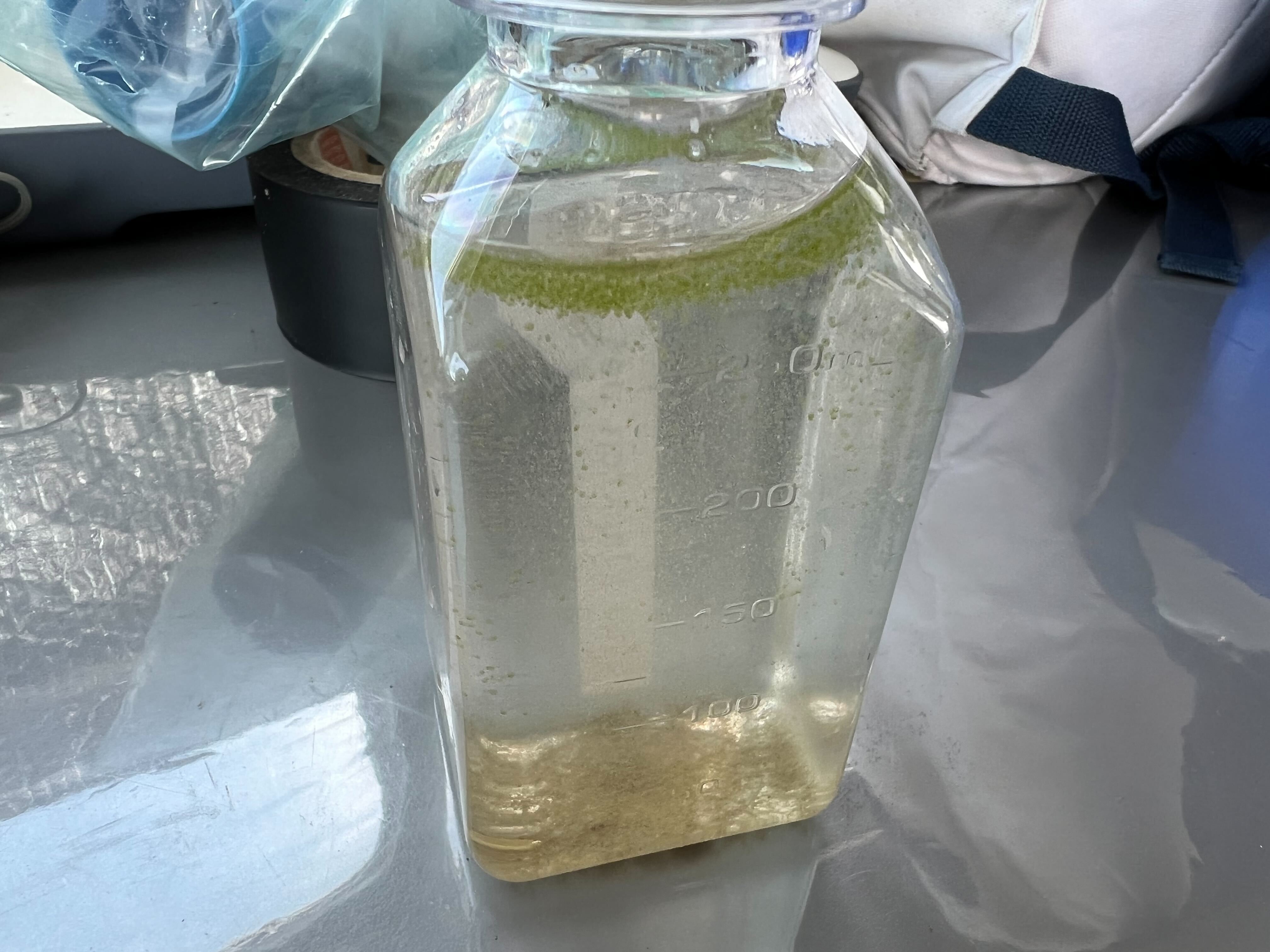

The sample of dinoflagellates, despite not being photosynthetic, was visibly green.

Collected seawater sample. Image via GEEK Lab.

Collected seawater sample. Image via GEEK Lab.

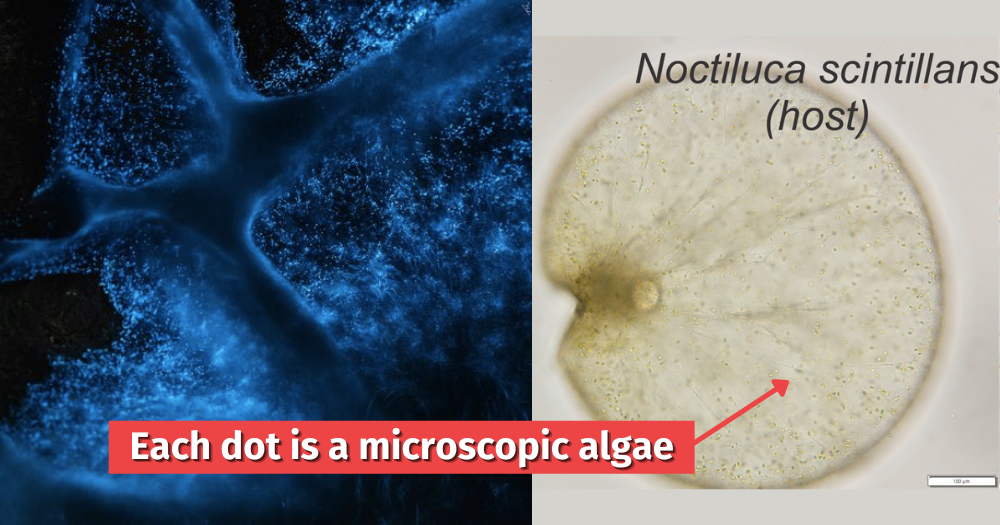

Under the microscope, Sim found that these dinoflagellates were hosts to thousands of tiny green dots, which he identified as a photosynthetic symbiont known as Pedinomonas noctilucae.

"The algae provides its host with food because it is able to photosynthesise, and the dinoflagellate provides shelter for the smaller cells," said Sim.

The flagellum is used by the dinoflagellate to ingest other plankton. Image via GEEK Lab.

The flagellum is used by the dinoflagellate to ingest other plankton. Image via GEEK Lab.

While they are both protists, Sim explains that the two microbes are genetically very distant relatives, "even further than between humans and fungi".

Unlike corals and their dinoflagellates, these two symbionts are capable of living independently.

Their symbiotic relationship could be a key part of how the dinoflagellate has been able to proliferate and bloom, according to Sim.

There have been similar records of this relationship in the west coast of India, Arabian Sea and Sea of Marmara in Turkey, but this is the first time it has been observed in Singapore.

A dying Noctiluca scintillans expelling thousands of symbionts. Video via GEEK Lab.

A dying Noctiluca scintillans expelling thousands of symbionts. Video via GEEK Lab.

Algal blooms not always a bad thing

When the bioluminescent plankton made waves last week, many netizens suggested that the phenomenon was bad news and an indication of poor water quality in Singapore's waters.

While algal blooms are often associated with killing marine wildlife, Sim said that it was a "very big misconception" that such phenomena are harmful.

"A lot of ecosystems depend on algal blooms, as they are a major primary producers of the sea," he explained.

Though microscopic, plankton are the base of the entire marine food web and play a significant role in marine ecosystems.

While algal blooms can be indicative of water pollution, they also occur naturally and appear seasonally.

"As for Singapore's case, I don't know of any major pollution for now, so it could be a natural phenomenon," said Sim, who added that this particular bloom was an anomaly.

The GEEK lab is building a baseline understanding of Singapore's marine plankton community and its biodiversity, a field which has largely been dominated by research in the temperate waters of the global north.

The team will be sequencing the DNA of the symbionts to uncover more about duo.

Previous harmful algal blooms

Top images courtesy of Toh Wei Yang and GEEK lab.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.