Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

At first impression, Vickineswarie Jagadharan seems just like an average Singaporean. She holds a 9 to 5 job and comes home each day to have dinner with her family in their cosy 5-room HDB apartment.

As she welcomes me courteously into her home — grabbing a stool for me to place my laptop on, double-checking that I am comfortable before we begin the interview — I get the sense that this is not the first time she is sharing her story.

But having the experience of sharing a personal story, especially one that is as tragic as Vickineswarie's, doesn’t mean that it gets easier each time, and this is apparent in how her family remains close by with a box of tissues in hand.

Because the story that Vickineswarie shares is one that is unlike her sprightly demeanour — she lost her only son to suicide in 2015.

A “very kind and loving” boy

As a single parent, Vickineswarie shared a particularly close bond with her son, Emmanuel.

She fondly recalls how, prior to his death, he used to make tea for her whenever she returned home from work. He would do the laundry and housework, and make sure that the house was in tip-top condition.

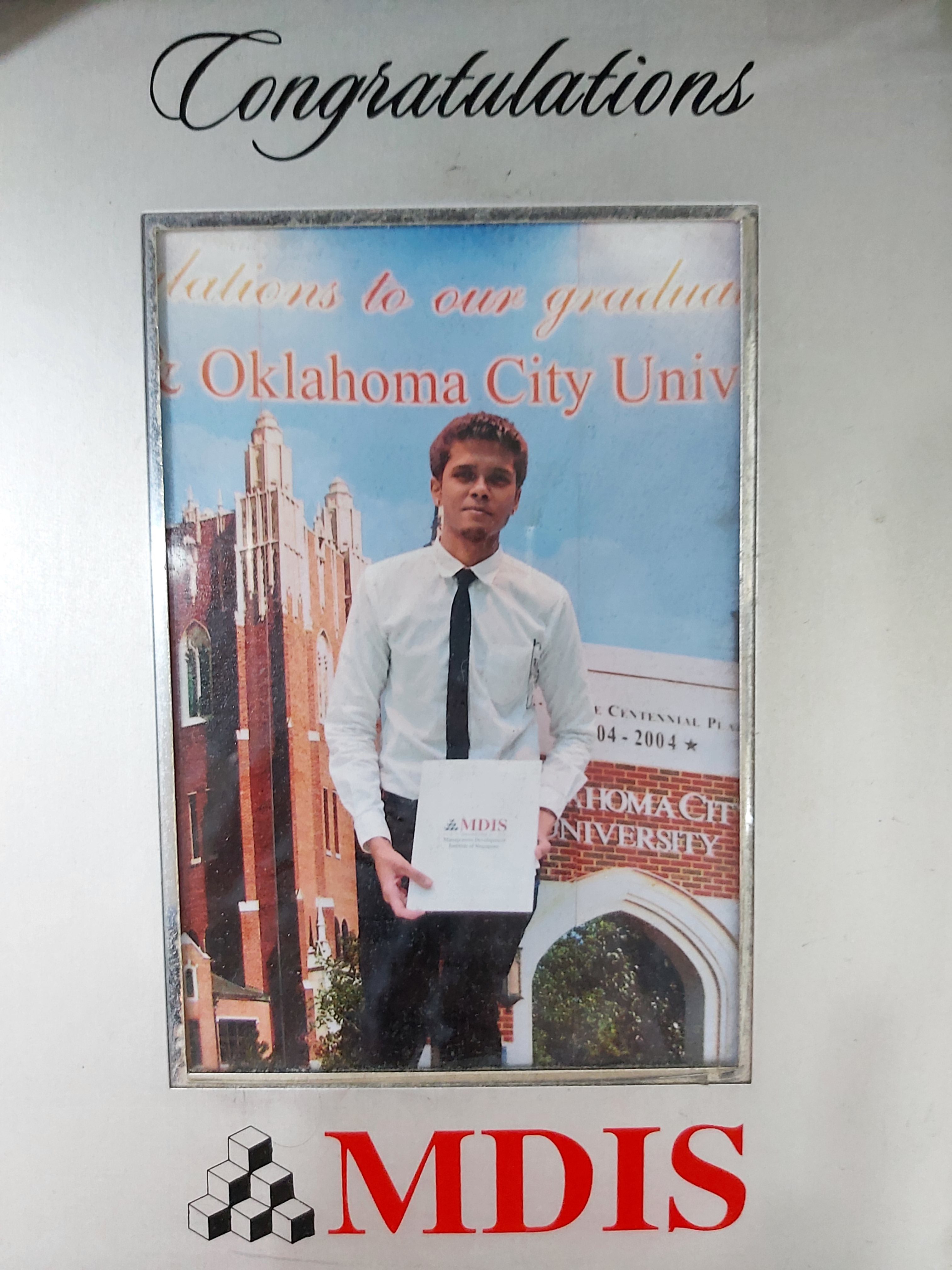

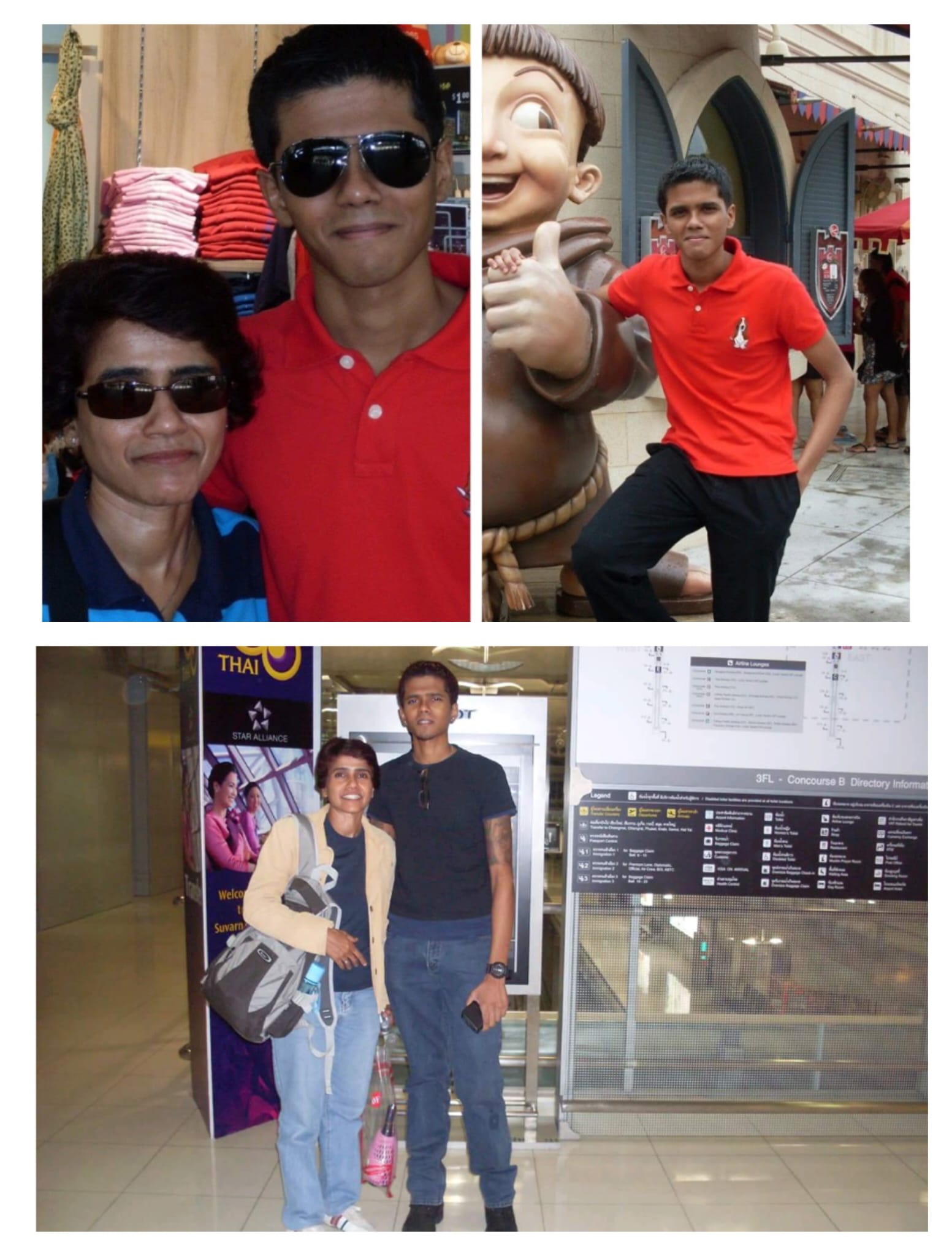

Photographs of Vickineswarie and her son Emmanuel. Photographs courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

Photographs of Vickineswarie and her son Emmanuel. Photographs courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

The mother-and-son pair spent a lot of time together. On the weekends, the pair would catch a movie at the movie theatres or go shopping together. Shopping was one of Vickineswarie's favourite activities because she would often ask Emmanuel for his input when she shopped for her own clothes.

“He was like a father to me I would say, because he practically did most of the cleaning [...] And even though he was 22 [...], even at that age, we still hug each other. I still tell him that I love him very much, and he also tells me that he loves me.”

But while Emmanuel was a caring and considerate son, Vickineswarie acknowledges that he was also a bit of a “perfectionist", surmising that part of it was due to her influence. Vickineswarie admits that she “was a perfectionist at one time" and realised over time that Emmanuel tended to also display traits of perfectionism.

Difficulty playing dual roles of mother and counsellor

As Emmanuel neared the end of his secondary school years, Vickineswarie observed that the accumulated stress of academics and societal pressures throughout his teenage years was taking a toll on him. Emmanuel was especially hard on himself, taking it upon himself to perform well. Even though he was doing well in his studies, Emmanuel became increasingly withdrawn and depressed.

He developed an irregular sleeping pattern where he would sleep throughout the day and remain awake at night, immersing himself in computer games till the wee hours of the morning. Temper tantrums, where he would lash out unintentionally at Vickineswarie, were also common.

At that time, Vickineswarie was pursuing her masters in Counselling Psychology and she understood that her son was going through mental anguish that was "truly painful".

But as his mother, she found it difficult to refrain from telling Emmanuel that his struggles were “part and parcel of growing up” and that he should pull himself together.

“I was trying to talk to him in a way [that was] like a counsellor, but I knew I couldn’t really have a counselling session with my son per se [...] I had to juggle with work and look after him at the same time. It’s not easy, as a caregiver [and a mother]. Emotionally, it was draining.”

Finding it difficult to draw the line between her personal and professional roles, Vickineswarie referred Emmanuel to the Child Guidance Clinic at the Institute of Mental Health for treatment.

Emmanuel was diagnosed with depression and was prescribed medication together with a treatment plan to regulate his mood. Over the course of a year, he attended his treatment sessions diligently and soon did well enough to be discharged from his appointments, and even successfully enrolled in his desired course of study, Mass Communications, earning himself a diploma in 2013.

Emmanuel receiving his diploma in Mass Communications. Photo courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

Emmanuel receiving his diploma in Mass Communications. Photo courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

But as he went on to do his degree programme, Emmanuel started spiralling again. The stress from academic and societal pressures was even greater now, and Emmanuel soon suffered a relapse.

Reluctant to seek help

When Emmanuel suffered a relapse, the tell-tale signs of a depressive episode were all too apparent for Vickineswarie.

Emmanuel started to isolate himself again, preferring to stay in his room and avoid socialising with others. When Vickineswarie tried coaxing him to share his struggles with her, he broke down several times and frequently voiced his desire to "end it all".

She tried to get him professional help again, but this time Emmanuel was reluctant to do so. At that time, the family was struggling to make ends meet, and Emmanuel was unwilling to seek help as he did not want to be another “burden” to her.

“There were days when he woke up and he would tell me, 'Ma, I wish I didn’t have to get up. I wish I didn't have to wake up.'

But I would always encourage him, I told him that he would get past this, that I would always be there to support him. And we would walk this journey together.”

Call it a mother’s instinct, but Vickineswarie sensed that her son's second depressive episode was different. Emmanuel had an air of resignation and became “very quiet”, constantly expressing guilt over the financial strain he was causing his mother and feeling that things were “beyond his control”.

“I just broke down”

On March 2, 2015, Vickineswarie left the house in the morning for work, as usual.

There was nothing to suggest that this day was going to be any different — except that it was. Emmanuel wasn't there to welcome her home in the evening because he had hung himself from the living room ceiling while she was away at work.

“It was very traumatic for me...I just broke down. I cried my heart out.

I was very helpless, not knowing what I should do at that moment. I was lost because I was the first one to see my son in that state. I was really lost.”

In that moment, Vickineswarie could not comprehend what had happened. Dazed, she rushed to cut her son's body loose, carried him down, and laid him on the ground.

She recalls frantically “running back and forth” from the living room to her prayer room afterwards, desperate for a sign from God that her beloved Emmanuel was still alive, but to no avail.

Had to remove all his photographs

It took Vickineswarie about two weeks after the wake to come to terms with the passing of her son. She was so preoccupied with the rites and rituals during the wake, and “the crying and the pain” that she failed to process the fact that Emmanuel had left her.

The hardest part was when she came home to an empty house after the funeral and had to remove all his photographs to cope with the loss.

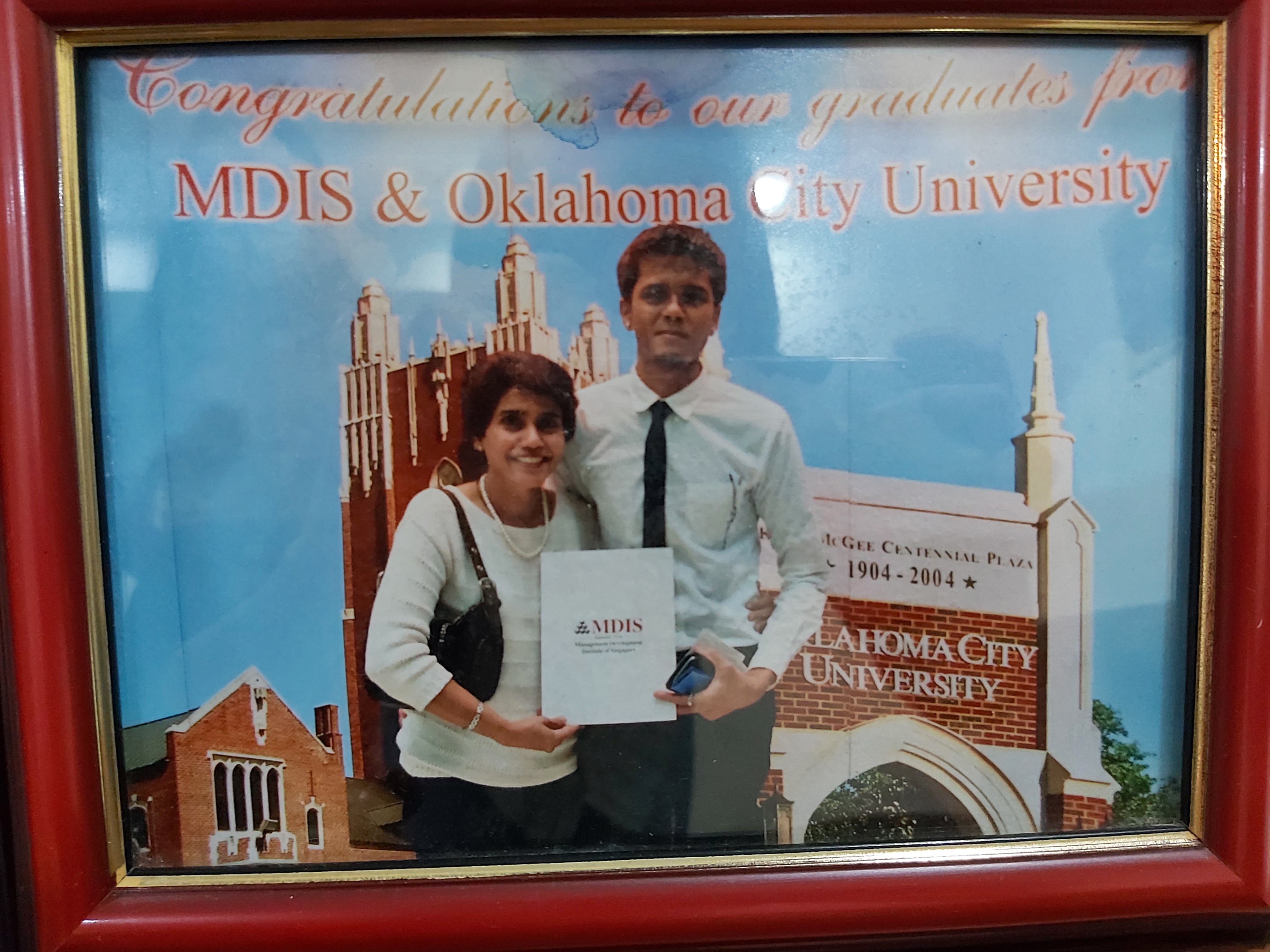

Vickineswarie with Emmanuel on his graduation day. Photo courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

Vickineswarie with Emmanuel on his graduation day. Photo courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

“I had to remove all his photographs, because I knew that the memories were going to hit me very hard, so I kept all of them in the cupboard. It took me a while...more than a month or so until I was ready [to bring them back out again].”

Adding on to the grief was the sense of guilt that soon crept up on Vickineswari and weighed heavily on her. She constantly wondered if she had done enough as a mother to prevent her son's death.

Seeking help to process grief and loss

Although she was a counsellor, Vickineswarie found it difficult to cope alone. She plucked up the courage to seek help from a family service centre at Admiralty, attending several counselling sessions to help her process her emotions.

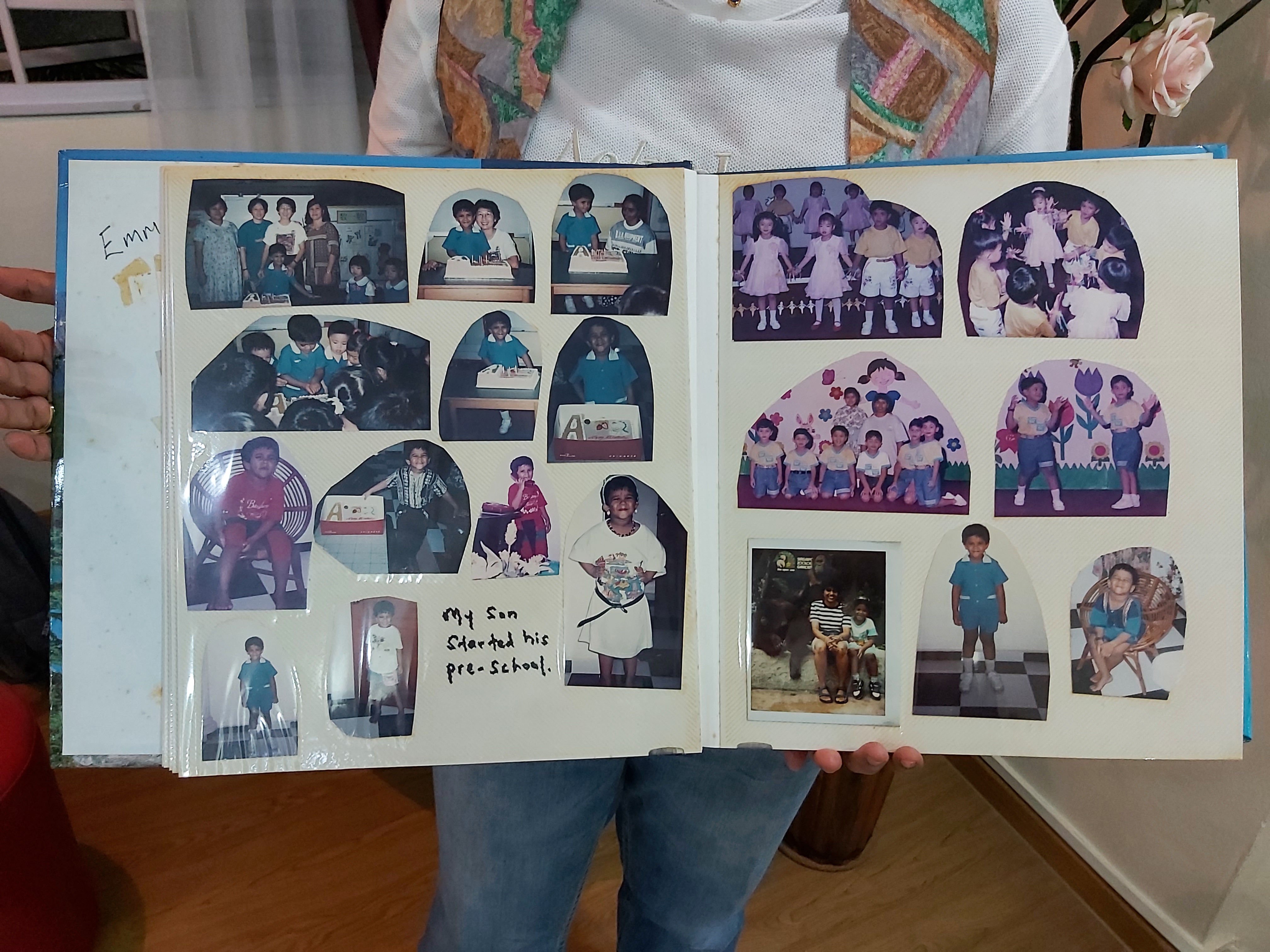

Childhood photos of Emmanuel. Photographs courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

Childhood photos of Emmanuel. Photographs courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

The sessions helped her to understand the stages of grief and to not rush the grieving process. More importantly, Vickineswarie learned to stop blaming herself for Emmanuel’s death, gradually coming to accept that she had done all that she could to help her son overcome his struggles.

“I realised that what my son went through was something that I couldn’t have avoided [...] I’ve come to realise that at that time, what I did was what I could do. And every person that takes their life, it’s not that they want to. It’s not that they wish for it, but they want to end the pain. And because of the pain, they come to a decision like that.”

“I want you to do what you have been doing, helping the children out there”

Having experienced the ordeal of losing her only son to suicide, Vickineswarie now advocates for more open conversations surrounding mental health, noting that there is a “taboo or stigma [that is still present when] talking about mental health issues" in Singapore.

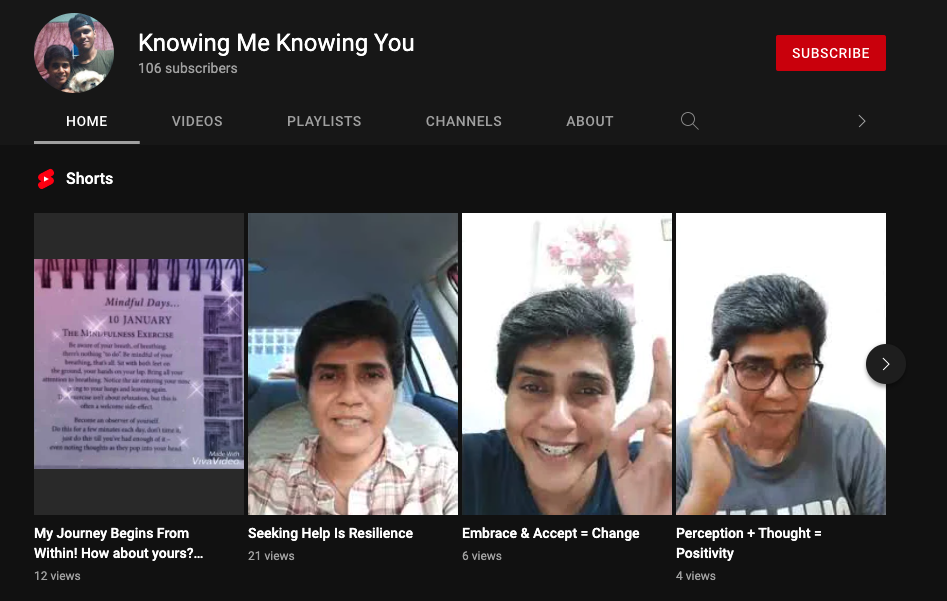

She does this by operating a YouTube channel titled “Knowing Me, Knowing You”, which is aimed at teenagers and parents.

Aside from family encouragement, she finds courage in a note that Emmanuel left before he passed on:

Ma, I want you to carry on in life, I want you to do what you have been doing, helping the children out there. I want you to go on and make it in life.

Her YouTube channel teaches teenagers and parents to recognise distress signals and understand how factors like familial pressures or body image issues can cause emotional and behavioural changes in a person.

Her channel also promotes mindfulness techniques that can alleviate anxiety.

Additionally, her personal experience with Emmanuel also motivates her to reach out to parents and urge them not to impose their beliefs on their children. As such, she hopes that her channel can connect with the wider community so that “no child will fall through the cracks”.

Not immediate, but eventual

Noting how Singapore is “slow” to have more open conversations about mental health, Vickineswarie acknowledges that her efforts to contribute to this movement may not see immediate momentum.

Nevertheless, she believes that “eventually, the message will go across”.

“Eventually more people will understand. Because when more of us do something like that, [the message] that goes across is love and care.”

To fulfil Emmanuel’s last wishes and give back to the community, Vickineswarie regularly volunteers with various organisations like Singapore After-Care Association, where she works as a befriender to ex-offenders to aid their reintegration into society.

She has also been volunteering with World Vision Singapore for more than 18 years — she continued to do so even during her emotional ordeal — sponsoring the education of two children under the programme. Vickineswarie tells me proudly that one of them has since graduated from college.

Awards received by Vickineswarie for her continued volunteering efforts. Image by Shynn Ong.

Awards received by Vickineswarie for her continued volunteering efforts. Image by Shynn Ong.

Beyond the local community, Vickineswarie also does volunteer work at children’s homes in Sri Lanka and Malaysia, humbly maintaining that she “tries her best to give something back to society”.

Not alone in this journey

Looking back, Vickineswarie admits that she should have sought professional help earlier, especially when she had to juggle work and care for Emmanuel at the same time.

“I don’t know what made me not seek help. Maybe I was afraid of what others would think. Then I realised that I needed to seek help [...] I needed my emotional cup to be filled as well.”

Like her, Vickineswari believes that many individuals who are mourning the loss of a loved one are still afraid of seeking help because they are afraid. To these people, Vickineswarie has an important message:

“I think that they need to know that they are not alone, that there’s help out there. They can reach out, talk to people. Because that’s what I did. Sometimes, you need the outlet to [express] your emotions instead of bottling everything up.”

When I’m having flu, I just go and see my GP. Why is it that when people want to go to IMH or seek any [psychological help], they are so afraid to go? I hope that one day people will be able to say, ‘Hey, I’m going to see a doctor at IMH’ freely, without being judged.”

Despite this, she has observed that more and more youths are beginning to seek help for their mental health struggles. As a school counsellor, she notes that many students have also come forward to seek advice from her, which is an encouraging trend.

“I am still journeying”

Speaking out about her experience not only allows Vickineswarie to reach out to the larger society, but also helps to ease her emotional pain and allow “[Emmanuel’s] memories to live on”.

I ask about her favourite memory with Emmanuel, and she chuckles before stating that there are “too many to choose from”:

“We used to [laugh a lot], sometimes he would lie on my lap and he’d say 'Ma, I feel so nice lying on your lap.'

[We watched] the whole Harry Potter series together...and even till now, whenever I see Harry Potter playing on the TV, I will sit down and watch.”

But remembering her son is bittersweet. Vickineswarie still has flashbacks of what happened on March 2, 2015, and occasionally finds herself shedding tears when she thinks of him.

A picture collage made by Vickineswarie of Emmanuel and her. Image courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

A picture collage made by Vickineswarie of Emmanuel and her. Image courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

At the end of the interview, I ask Vickineswarie if she is now able to fully accept and move on from the passing of her son. She ponders for a moment before answering, “I am still journeying. I think I am moulded with the pain.”

“People always think that as time goes by, you sort of let go and forget. But what I have come to realise is that...I am moulded with the pain. Maybe now the pain is less intense, but I’m still being moulded with the pain.”

Helplines to call

If you or someone you know are in mental distress, below are some hotlines you can call to seek help, advice or a listening ear:

- Samaritans of Singapore (24 hrs): 1800-221-4444

- Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

- Institute of Mental Health Mobile Crisis Service (24 hrs): 6389-2222

- National Care Hotline: 1800-202-6868

- Tinkle Friend Helpline (for primary school-aged children): 1800-274-4788

Top image by Shynn Ong, courtesy of Vickineswarie Jagadharan.

Follow and listen to our podcast here

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.