COMMENTARY: "Food delivery and other platform service drivers provide essential services. The least that we can do is try to get the riders back to their families in one piece, at the end of each shift."

Our contributor Abel Ang calls for injuries and fatalities for delivery riders and platform workers to be tracked in the same way that workplace safety and health is tracked for many sectors in the Singapore economy.

Abel Ang is the chief executive of a medical technology company and an adjunct associate professor at Nanyang Business School.

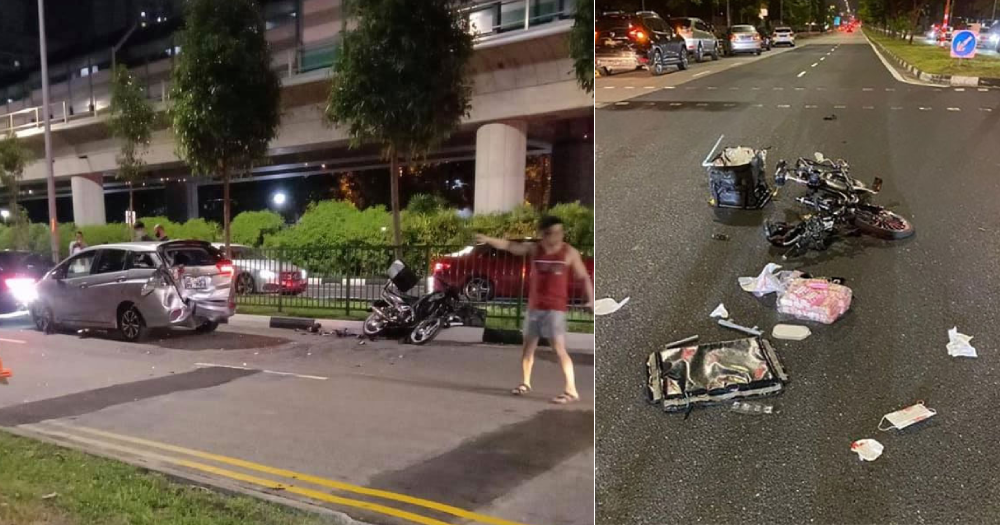

Food delivery is a dangerous business.

90 per cent of food riders interviewed by the Straits Times in 2019 reported that they had an accident or knew of fellow riders who had met with accidents.

Last year, in April, delivery rider Mohammed Ali got into an accident which left him in a coma for seven days. According to media reports, he had fractures all over his body and critical brain bleeding that had to be relieved with an emergency surgery, where part of his skull was removed to alleviate pressure on the brain. His medical bills purportedly amounted to more than S$100,000, which were covered by a crowdsourcing campaign that went viral.

A month earlier, in the same year, food delivery rider, Simon Teo, was killed at Kovan after being hit by a Mini Cooper. The 34-year-old driver of the car was arrested for drink driving and careless driving causing death.

Food delivery has claimed lives of riders on the road, but based on previous media queries, neither the police, Ministry of Manpower (MOM), nor food delivery companies track the figures.

Tracking workplace safety

According to the government, there are about 80,000 people out on the roads plying their trade on platform apps each day. This group includes private hire drivers, goods and food delivery workers.

To track workplace safety and health, MOM produces an annual workplace safety and health report. The report compiles statistics for workplace safety and health for many sectors that are sizeable employers in Singapore. This includes construction, manufacturing, and the wholesale and retail trade sectors.

The latest full year report in 2020 recorded 30 workplace fatal injury cases, of which only three deaths were from traffic accidents. Teo’s death alone would have accounted for a third of the traffic accident deaths in the MOM report, if it were captured as such, but unfortunately platform worker’s injury and fatality statistics are not captured by the report.

[UPDATE: July 19, 6:05pm: MOM has responded to the article, clarifying that workplace fatality statistics for platform workers are tracked by MOM and included in MOM’s Workplace Safety and Health Statistics reports under “Traffic Accidents”.]

The link between the safety of delivery workers and workplace safety and health was established by a circular released in August 2018 by MOM, Singapore Police and the Land Transport Authority (LTA).

The circular specifically calls out the duties and responsibilities of the platform companies under the Workplace Safety and Health Act (WSHA). It emphasizes that even if the riders and drivers on the platform are self-employed, “companies facilitating delivery work need to ensure that reasonably practicable measures are taken for the safety and health of delivery riders.”

This group of platform workers is sizeable — cumulatively accounting for a whopping 3 per cent of the resident workforce of the country — so it would seem reasonable for road safety statistics to be collected for this group.

Workplace accident reporting provides an objective way to track injuries and deaths of food delivery riders and other platform workers. Without good data to guide the discussion, how are companies going to improve? And how will the authorities be able to pick out errant employers who are flouting their responsibilities to their workers, resulting in unnecessary injury and even death?

Growing attention surrounding protections for delivery workers

The plight of delivery workers has grabbed the attention of the government. MOM launched a public consultation on strengthening protections for this group of workers at the end of 2021.

Much of what is being deliberated upon revolves around the protections and status of delivery riders as employees. According to the committee’s call for feedback, these workers “resemble employees in that they are subject to significant control by platform companies over the jobs they receive and accept, as well as the fee for their services.”

The workplace injury topic is also being reviewed by the committee. According to the committee’s request for comments document:

“Work injuries may leave platform workers in a precarious financial position if they are unable to work as a result of the injury. This loss of income during the duration of recovery makes covering medical bills extremely difficult. Serious injuries resulting in permanent disability could lead to a loss of future earning power, for which platform workers may not be compensated.”

The committee is targeting to complete its work by the second half of this year. In the meantime, to signal how important this issue is, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong did his round of visits to workers providing essential services during the Chinese New Year period.

This year PM Lee did so on the eve of New Year instead of the customary first day of the New Year. He did this to meet with food delivery riders while food outlets remained open prior to the festive holiday shutdowns.

The visit follows Mr. Lee’s National Day Rally speech in August 2021, where he cited that delivery riders “lack the basic job protection” that most employees enjoy because they are not covered by employment contracts with the online platforms they work for.

German example

A German case where a delivery rider sued his employer could be instructive considering the growing interest in the rights of platform workers. The German Federal Court concluded in March 2021 that the app was the rider’s digital boss and that he was indeed an employee of the delivery platform company.

In addition, the court also ruled that the delivery company should provide the rider with the essential tools to do his job, which included a safe means of transport, and a smartphone with data access to receive and respond to instructions from the app.

The app company argued that their delivery workers were not "significantly burdened" by having to use their own equipment, since they already had a means of transport and smartphones.

The German Federal Labour Court disagreed, saying that the practice "unreasonably disadvantages" the app's riders who shouldered the risk for damage to their work equipment. In addition, riders have to pay their smartphone monthly usage charges themselves.

The court ruled that the position taken by the app company “contradicts the basic legal idea of the employment relationship, according to which the employer must provide the work equipment essential for the performance of the agreed activity and ensure that it is in good working order."

Getting riders home safely

The jury is still out on whether delivery riders and platform workers are to be recognised as employees of the platform companies, pending deliberations of the MOM committee.

However, a good start would be to track injuries and fatalities for delivery riders and platform workers in the same way that workplace safety and health is tracked for many sectors in the Singapore economy.

In addition, it would be good to explore the possibility of providing safer equipment and tools to riders. This could go beyond providing a means of transport to them, but to provide regular maintenance so that the equipment used in the deliveries adhere to a minimum standard of safety and operation.

The platform companies can also consider providing smartphones with apps pre-installed, which promote increased safety on roads while deliveries are taking place.

We would not allow healthcare workers to go to work without personal protective equipment (PPE) during a pandemic. So why should food riders and platform workers not be provided with essential equipment which allows them to operate safely, in the same pandemic that has generated exponential demand for their services?

Working in the sector is tough and thankless as it is. As reported in the Straits Times, GrabFood rider Ramdan Samat said, "food delivery riders often work long and odd hours and suffer from fatigue. We also have to deal with impatient customers who press us to deliver their food fast."

Food delivery and other platform service drivers provide essential services. The least that we can do is try to get the riders back to their families in one piece, at the end of each shift.

Top photo via Elfy Andriann, Roads.sg Facebook

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.