Alexander Woon is a Lecturer at Singapore University of Social Sciences, School of Law, and practices law as Of Counsel with RHTLaw Asia. He was previously a Deputy Public Prosecutor in the Financial and Technology Crime Division of the Attorney-General’s Chambers.

By Alexander Woon

Singapore has seen a spate of sophisticated online scams lately.

First, OCBC was targeted, with over 400 customers affected and losses of over S$8.5 million. Recently, DBS and the Supreme Court have also been targeted by scammers.

The question is when scams occur, who is responsible? And who bears the losses?

How the scams work

These scams are known as “phishing”. They are a form of social engineering in which the scammer attempts to trick a victim into disclosing personal information like bank account numbers, passwords or One-Time Passwords (OTPs) which would allow the scammer to do a number of things, such as gaining control of the victim’s bank account. The scammer might even change the account password or associated phone number, locking the victim out of the account.

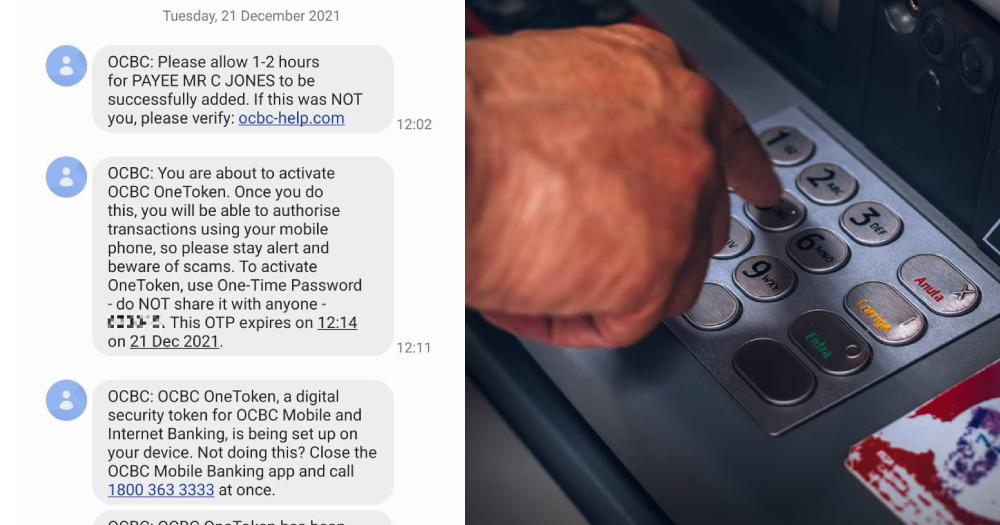

In OCBC’s case, the scam was reportedly very sophisticated. The scammers sent SMSes to the victims using a “spoofed” number to make it appear that the messages were coming from OCBC. Thus, the SMSes appeared in the same chat thread along with legitimate messages from the bank.

Victims were then asked to click on a link in the SMS, which brought them to a webpage that was set up to look like OCBC’s website. The webpage asked for personal information, which once keyed in, was made available to the scammer who could then take control of and drain the victim’s bank account of money.

The DBS scam appears to be similar, with SMSes supposedly from DBS Bank being sent to customers with links for them to click.

The Supreme Court scam is slightly different – emails are sent to victims from what appears to be a legitimate web domain “judiciary.gov.sg”. The victims are then invited to submit personal information to the “judiciary”, which once in the possession of the scammers might allow them to go on to commit identity theft or, perhaps with other necessary information obtained through other methods, to access the victim’s bank accounts.

These scams are all similar in that they attempt to create the illusion of legitimacy to trick victims into disclosing sensitive information.

Different types of liability

The issue of responsibility for scams is complicated. There are several types of liability that might arise and different parties are involved.

First, criminal responsibility is placed on the scammers themselves. Scams are a form of cheating, which is an offence under the Penal Code. The Police can investigate if the scammers are found, they can be brought to court and prosecuted. If found guilty, they can be sent to jail or fined. A compensation order can also be imposed on the scammers to force them to compensate the victims for any loss.

Second, victims might be able to sue under civil law – this is part of the law of tort, which means civil wrongs. They can sue the scammers, assuming that the scammers can be found, for losses suffered. They might also be able to sue the bank if the bank somehow contributed to the loss – this might be the case if the bank’s security system was weak or if the bank did not take any action to stop a fraudulent transfer, for example.

Third, there might be regulatory action taken against the banks. MAS said on Jan. 17 that they will consider “supervisory actions” following OCBC’s internal review to identify deficiencies in their processes.

In a separate statement on Jan. 19, MAS also announced that they will work with banks in Singapore to put in place safeguarding measures within the next two weeks. These measures include removing clickable links in emails or SMSes sent to retail customers and for the threshold for funds transfer transaction notifications to be set at a default of S$100 or under.

Possible remedies for victims

These types of liability also map neatly onto the avenues of recourse that victims might have.

First, a victim can make a police report that they have been scammed. This allows a criminal investigation to be started. However, in many cases, the scammers are located overseas and therefore beyond the jurisdiction of Singapore’s enforcement agencies. Further, the money drained from the victim’s account is often quickly moved out of jurisdiction and laundered through money mules, making it untraceable. Or it might be spent. Therefore, in many cases, criminal investigations hit a dead end.

Second, a victim can try to pursue civil action. If the scammers can be found and identified, they can be sued in Singapore. But in most cases, the scammers are anonymous and probably overseas, so this is often also a dead end.

Alternatively, if there were lapses on the part of the bank that contributed to the success of the scam, the victims might be able to sue the bank, which is known and present in Singapore.

However, they will need evidence to prove that the bank is liable, which might not be easy to obtain. Legal proceedings are also costly and risky – there is no guarantee that the court will find the bank liable. Even if the case is successful, the amount recovered might be less than the legal fees paid, or it might be impossible to enforce the court’s judgement against the scammers if their assets are located overseas.

Third, a victim can complain to the regulator, in this case, MAS. The regulator might then take action against the bank. However, this does not necessarily mean that the victim will be compensated, as the issue is between the bank and the regulator. The focus of the regulator’s investigations will be on the bank’s failure to comply with regulations, and the bank may be sanctioned if any lapses are found.

Fourth, the banks may offer voluntarily compensation but this is not a legal requirement. This is what OCBC appears to be doing, as it has now promised to fully reimburse all victims of the recent SMS scam. The bank does this out of goodwill and to save its reputation, and this does not necessarily mean that the bank is admitting fault.

Practical steps for scam victims

Frankly, there is often little that can be done once a scam is successful. The scammers are usually unknown and the money is often moved overseas and dissipated almost immediately. Unless the bank is willing to voluntarily compensate the victims, there is often little chance of successfully recovering the money.

Since prevention is better than cure, it is important to take steps to protect yourself against scams. This includes educating yourself on the latest scams – pay attention to advisories from banks and also from the Police and National Crime Prevention Council. The Open Government Products team, part of GovTech, has also developed an app called ScamShield that helps to block unsolicited calls and SMSes. The website Scamalert.sg also contains information on current scams.

Once a scam has been detected, the victim can take steps to block their account to prevent outward transfers. This depends on the bank being responsive and having a working fraud prevention processes.

Once the scam has been completed and money drained from the account, the victim must act quickly if any remedy is to be successful.

A Police report can be made – if made in time, the Police might be able to trace the transfer and freeze the money in the receiving account, pending further investigations. This will prevent the money from being spent and, if all goes well, it might be returned at the end of the criminal case.

The victim might also want to consult a lawyer and take legal advice. A lawyer may be able to advise the victim on available options and their relative chances of success. It is impossible to say in the abstract what the best course of action would be – it depends greatly on the facts and circumstances of each case, which is why a properly qualified lawyer is needed to assess the situation. It may be useful to hire a lawyer if the victim is considering pursuing civil action against either the scammers or the bank.

For those who cannot afford a lawyer, it might be possible to seek help pro bono, that is for free, from various sources like the Law Society Pro Bono Services office or the Community Justice Centre.

Ultimately though, a victim of a scam must recognise that despite best efforts, the money may never be recovered. There are no mandatory compensation laws in Singapore that would oblige a bank to compensate the victims where it cannot be proved that the bank was at fault.

Whether there should be such victim protection laws is likely to be a key policy issue going forward, as online scams continue to be the fastest-growing segment of crime in Singapore.

Top photo via Mothership reader, Unsplash/Eduardo Soares

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.