Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Wilfred Cheah grew up in a two-room rental HDB flat at Lower Delta Road.

“Growing up, I didn’t come from a rich family,” he said. Home was a small unit packed with six other family members – his grandmother, his parents, his uncle, and his two siblings.

As a young boy, he recalled seeing many of his friends playing with new toys.

Cheah often found himself gawking at the toy cars and houses displayed in a nearby mamak shop, wishing he could have one of his own. But, he couldn’t always get a brand new toy whenever he wanted one.

“Sometimes, we don’t have enough money to buy toys. So, I thought to myself maybe I can make my own.”

And that was when he first started building toy houses for himself, fashioning them from cardboard, paper, and even wooden sticks.

“It was not very nice but at least, can play lah,” Cheah remarked.

Today, the 56-year-old has moved on from simple cardboard houses to beautiful miniature dioramas of hawker stores, homes, chapels, and more.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Never had a chance to pursue art

You could say that Cheah always knew that he had an artistic streak in him.

He loved art from a young age and often drew, painted, and created three-dimensional artwork of the things around him.

He wanted to pursue art in polytechnic and even hoped to go to Baharuddin Vocational Institute (Singapore’s first tertiary school for designers and craftsmen) to study graphic design.

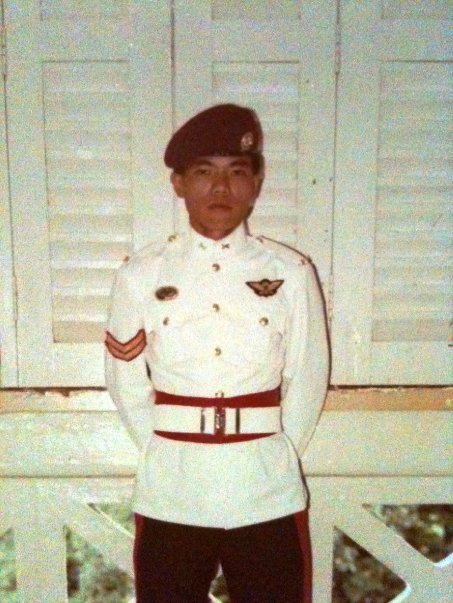

Unfortunately, Cheah flunked his O’Levels and signed on to the army instead. He went on to serve as a regular eight years – six of which were spent as a commando in the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF).

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Despite not being able to pursue his goal of developing his artistic skills, Cheah enjoyed his time in the army.

He appreciated the rigour of training, which he said contributed to his “never quit” attitude today.

Being a commando is worlds apart from creating intricate dioramas, and so it came as a surprise to me when Cheah identified parallels between the two.

“Improvise, adapt and overcome,” he said, are words he still lives by today.

“I was a commando. When we were in the field and something went wrong, everyone looked at me to lead them. I had to think of what I had and how I could use it to get us around or over the situation.”

Cheah applies this "can-do" attitude to his miniature work as well, explaining that his mindset, even when working with very limited materials, would be to "find a way to make use of it".

His time in the army drew to a close when he got married and decided to get a 9-to-5 job.

“I still wanted to do something I like. So, I read up on graphic design and interior design.”

He struggled to pick between the two, but eventually decided to pursue a career in interior design as he thought the work would be more intimate and personal to the clients he served.

Fortunately, he had a friend who referred him to an interior design company. However, with no prior experience or education in interior design, Cheah had to start at the bottom.

“I had to take a pay cut, almost half of what I was earning,” Cheah said.

Undaunted, Cheah read interior design books, went down to construction sites, and spent many nights honing his skills.

28 years later, Cheah has worked on an array of interior design projects, from homes to hotels, and even showroom flats and restaurants, and runs his own design consultancy which he started in 2014.

Pandemic hobby

Cheah used to travel at every possible opportunity.

But when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, he found himself with a lot more spare time — time which he could spend on his old hobby of making dioramas and miniature models.

From late 2019 to early 2020, he worked on some of his first projects including a replica of his old home in Lower Delta Road, his childhood mamak shop, an old-school ice cream vendor, and a figure of his younger self in a red beret, amongst other things.

A replica of his childhood home at Lower Delta Road. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

A replica of his childhood home at Lower Delta Road. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

An old-school mamak shop. Cheah had to research old magazine covers and food packaging to recreate what he saw almost 50 years ago. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

An old-school mamak shop. Cheah had to research old magazine covers and food packaging to recreate what he saw almost 50 years ago. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

A schoolgirl excited to get her ice cream. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

A schoolgirl excited to get her ice cream. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

A replica of Cheah during his army days. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

A replica of Cheah during his army days. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

He posted the dioramas on Facebook and was soon flooded with messages and comments by interested buyers.

And so, in June 2020, Cheah decided to commit to being a full-time miniature artist. Evidently, his works are in high demand; he has a waitlist of projects that extends to August 2022.

Making a miniature piece

Cheah never says no to a request by an interested buyer.

“I like the challenge and I also can learn along the way.”

If there is a portion of the model that he isn’t sure of, he'd do up the rest of it first. But as he works, he'll think of how he can assemble a part of his diorama.

Often, he'll experiment with different materials to see if it works first.

Sometimes, it turns out just the way he wants. But if it doesn't, he'll have to try again.It usually takes about two to three weeks to complete one miniature model and his models are usually no bigger than 70cm in length and width.

“My models are normally not so big. I want to make sure the customer can display it on a table or a shelf. If I make it too big, where are they going to put it?”

He works on his miniatures from 8am to 8pm every day, even on public holidays.

“It’s something I like to do and enjoy doing. So I never think like, I must rest on public holidays. No.”

He admitted, though, that it can be physically tiring after a while.

“You have small movements so you don’t actually feel anything. But then when you stop, wah, there’s this stiffness and it’s a bit painful.”

Cheah, who used to have perfect eyesight, now needs reading glasses when working on smaller and more detailed parts of his models.

He whips out his iPhone and flips through his photo album to show me parts of his diorama that are smaller than his fingertips.

These plastic guns are one of the toys that can be found in traditional mamak shops. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

These plastic guns are one of the toys that can be found in traditional mamak shops. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

You'd need a very tiny a spoon to pry the lid off these tin cans. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

You'd need a very tiny a spoon to pry the lid off these tin cans. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Miniature lanterns with hand-drawn designs. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Miniature lanterns with hand-drawn designs. Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

A home office

As we chatted, Cheah gave me a small tour of his workstation which turned out to be a small table at the end of his kitchen table.

Lined with a green cutting mat, the table was very neat and organised.

In a trolley by his workstation, he had a pail filled with paint brushes with dried-up paint smeared along the handles. Another container held tools like scissors, rulers, and tweezers.

Image by Alfie Kwa.

Image by Alfie Kwa.

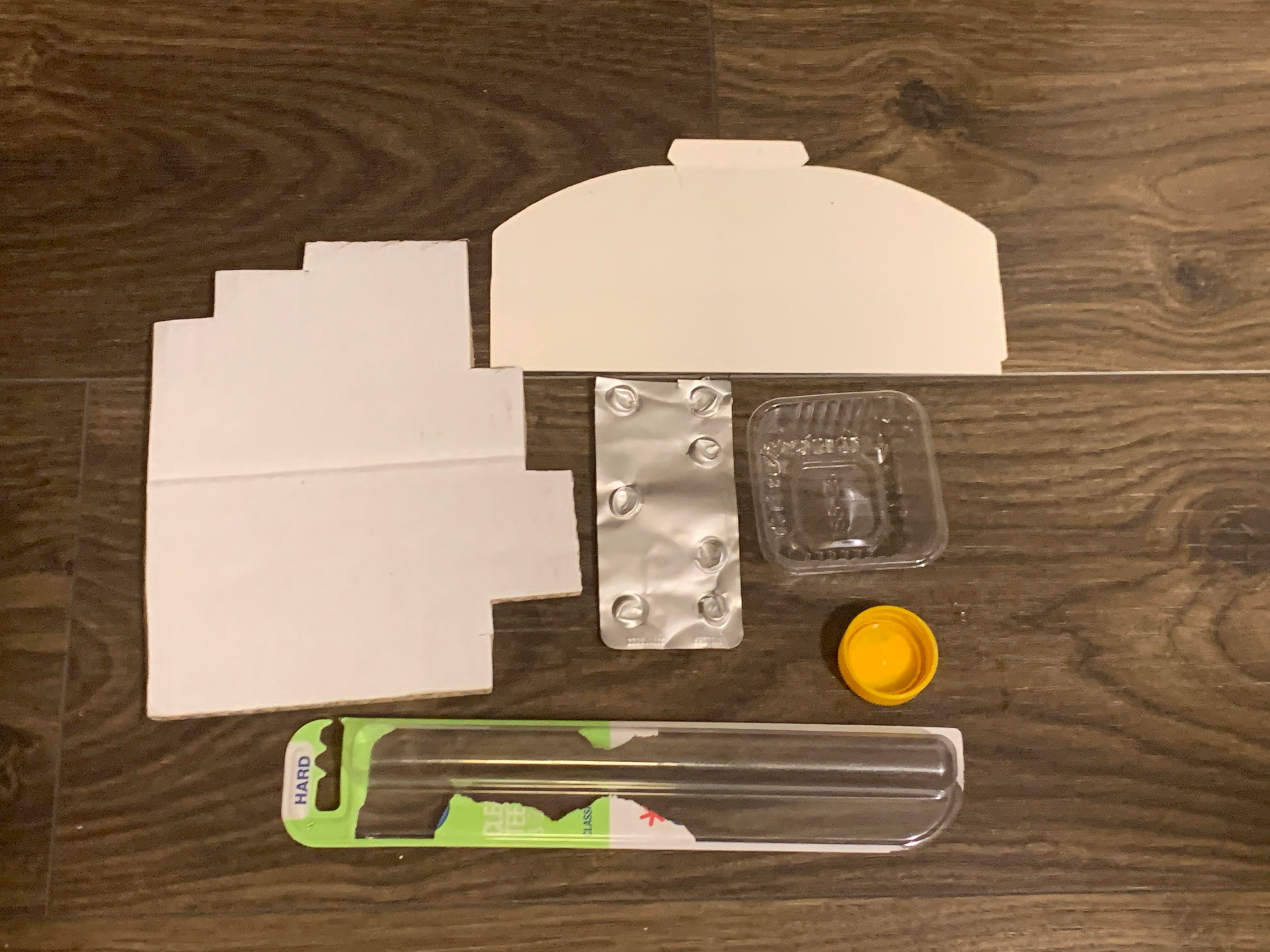

A pile of cut-up styrofoam and fragments of a cardboard box sat on the floor while another box held odds and ends like the plastic packages that come with mooncakes, bottle caps, raffia string, bubble wrap, and empty blister packs.

Image by Alfie Kwa.

Image by Alfie Kwa.

“Natural light is very important. It helps me see better,” he said as he gestured to the large windows behind his work table.

Finding the right materials

Cheah walked over to his workstation several times during the interview, to retrieve some of the materials that he brought up.

For about 20 minutes, all we talked about was the grooves, textures, thickness, and thinness of materials he had set aside to use for his upcoming projects.

“I always collect these items when I see them. If I see someone throw away their TV or refrigerator box downstairs, I will go and take it.

Cheah’s knowledge of materials and his passion for finding the right ones for his models was so evident:

“That kind of box is very strong, good to use.”

“See, this can be a pot or a hat. But sometimes, this one is also too big.”

“Look at these packages, see the curves, it’s quite different. Maybe I can use it for something next time.”

Some of the materials he collected. Image courtesy of Wilfred Cheah.

Some of the materials he collected. Image courtesy of Wilfred Cheah.

Finding the right materials obviously takes a lot of patience, but the perfect choice can sometimes come to Cheah in a moment of inspiration.

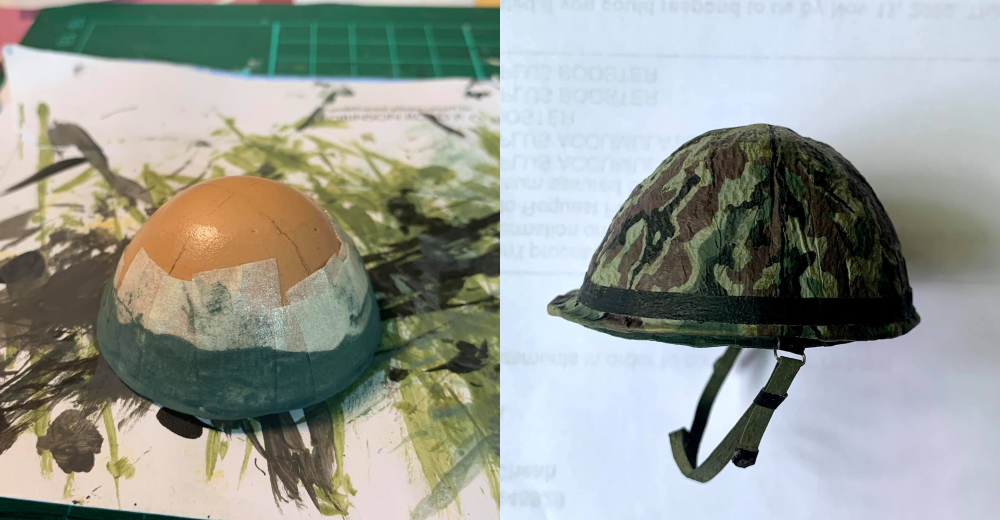

When he was working on a soldier figurine, he scratched his head trying to figure out how to make a helmet.

Cheah got stuck trying to find material that was exactly the right shape and size.

But the answer finally came to him one morning when he was eating soft-boiled eggs:

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

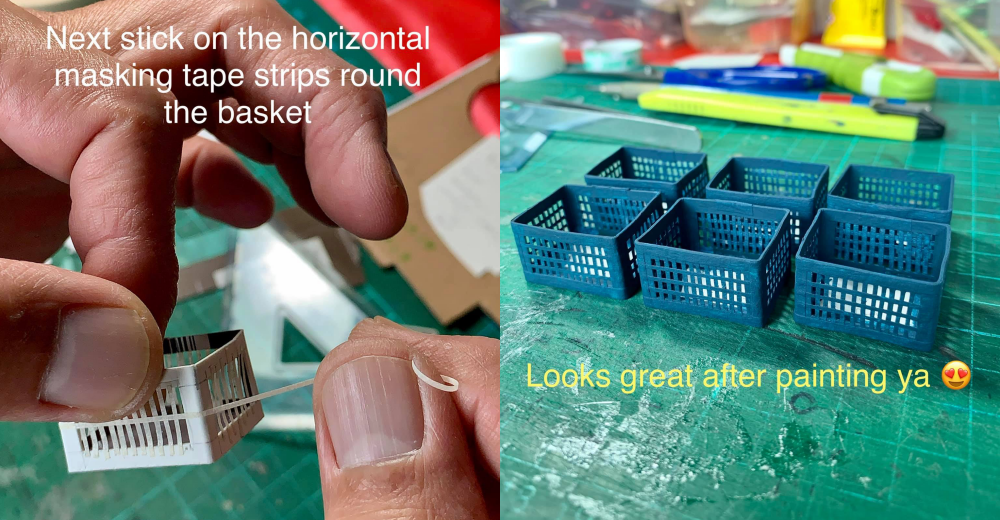

Here are some of the other everyday materials he’s transformed:

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Attention to detail

Even though Cheah makes his dioramas for sale, he said that it pains him to give them dioramas away.

“I looked at it for such a long time, thought so much about it, that they became my babies.”

Unfortunately, I could only see a couple of his models at his home since most of them have been sold.

I did see his latest project — a replica of a customer’s dad’s dessert shop, still in its early stages, with just the walls and the floor tiles built up.

As I looked at the replica, something caught my eye: A single broken tile inside the stall.

Cheah had noticed the broken tile from photos provided by the customer.

Others might overlook that broken tile but to Cheah, it was extremely important to include:

“What if his father always trips over the broken tile every day? Without that detail, he may not feel like it’s his shop I modeled it after.”

The one project that best highlights Cheah’s attention to detail is also his favourite one so far: A replica of his father-in-law’s 44-year-old provision shop in Teck Ghee Market.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

“Nothing much changes in the shop. Some of the packets at the back have been there for so many years,” said Cheah.

As the model was meant to be a surprise gift, Cheah secretly went down to take photos of the store and took note of everything he could – a plastic bag of kopi hanging on the wall, a rusty old fan in the corner, the scratches on the water pipes, and the dirt-stained tiles.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

Image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

His father-in-law was so moved when he first saw the diorama that he wept.

“So, all the details that you add in is how you give life to the miniature. And this is actually how it captures the person's heart and feelings when they look at it because everything is exactly the same.

[If] it can touch the person's heart or the memory, then they’ll start remembering all the stories that come from that little thing.”

No future plans

As for long-term plans, Cheah doesn’t have any for his miniature work.

“I don’t really call it a business,” he added. He takes the work as a retirement hobby and just wants to do what he’s passionate about and make some money while he’s at it.

He did think about teaching classes, but he doesn’t plan on doing so anytime soon as he doesn’t think he’s qualified to do so.

However, he recently compiled photographs of all his miniature artwork into a book titled “Trash to Treasure” which has sold 150 copies over the past two weeks.

Who knew that things that are commonly seen as trash — like a tip of a chopstick or an eggshell — could be transformed into something completely different, and valuable even.

Looking at Cheah’s collection of bits and pieces, I struggled to see the potential that he saw in them.

But every time he looked at them, his eyes lit up as he excitedly explained what he saw – sauce bottles in a provision store, a helmet for a soldier.

Being able to find inspiration in the mundane and ordinary — that is the mark of a true artist. This new fan will be closely watching his Facebook page to see what he puts out next, and I’m willing to bet that I won’t be disappointed.

Follow and listen to our podcast here

Top image via Wilfred Cheah/FB.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.