COMMENTARY: "The new (and improved) news regime must not only aim to ensure the survival of SPH (and Mediacorp) but must also encourage diversity of news sources."

Ang Peng Hwa is a professor at the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University, where he teaches and researches media law and policy.

By Ang Peng Hwa

Recent media reports, including an interview with retired minister Khaw Boon Wan, hinted at the possible direction of the restructuring of the papers in the Singapore Press Holdings stable. The direction suggests that the restructuring, led by Mr Khaw as chairman of the new SPH Media Trust, will be focused only on SPH.

From my research, I think that such a focus is off the mark. Within four years, if the attention is only on SPH, we will be revisiting this debate of how to keep our leading news organisation viable except that the crisis in the second round will be an even worse one.

The restructuring must aim to strengthen not just SPH but the entire news media eco-system so that our leading local news outlets will attract readers. The new (and improved) news regime must not only aim to ensure the survival of SPH (and Mediacorp) but must also encourage diversity of news sources.

That is, the new rules must allow for and encourage competition in the news business.

The losses on the media front could not be contained

Newspapers all over the world have suffered declines in advertising revenue, circulation, profits, and prestige. The board and management of SPH cannot be faulted entirely for the decline. It is an inevitable trend.

How bad is it? It’s so bad that the media part of the enterprise cannot stand on its own feet financially. The company cannot be privatised or sold. It will therefore have to be funded by the government or the public or both.

The fault lies partly in the stars in that we are a small country. With a total population of less than six million, and with two dominant languages, the media market is small.

The Scandinavian countries with populations of around five to six million, such as Norway and Denmark, have been subsidising the press for some decades. My research also found that news organisations in Austria and Switzerland had subsidies from their governments too. All these are well-run countries that rank high in both liveability and press freedom indices. And so to these countries we turn to understand press subsidies.

Political support is essential

As is often the case with research, there were many surprising finds. The first was that it was political support for press diversity, not sustainability, that led to the start of press subsidies.

In Sweden, the press subsidy was first proposed by the government of the day in 1971 because the newspapers were right-leaning on the political spectrum while the electorate and the government were left-leaning. Concerned that their views might be left out, the Swedish government encouraged diversity to ensure that the views from the left were disseminated. Fostering diversity meant supporting a range of newspapers—including those serving regional languages or dialects—as well as serving small communities.

In the early 1990s, Scandinavia had their own economic crisis and the support for diversity later morphed into support for viability. The lesson from press subsidies during this period is that incumbents may exploit them for profit and suppress the competition.

Instead of investing in people and equipment, for example, some of the subsidies in Scandinavia went into the owners’ pockets. If press subsidies in Singapore went to SPH only, notwithstanding declarations otherwise, there’s a possibility that the same would happen.

What research into the utility and impact of subsidies are agreed upon is that such an approach is not viable in the long run.

That is, subsidies to keep the media afloat for the short term will not keep them afloat for the long term. Subsidies must enable the media to attract and retain readers. Encouraging diversity encourages competition which then contributes to long term viability.

Models for funding the news media

There are three models for funding the media in Europe:

1. Licence fee tied to TV ownership,

2. “Excise duty” where each household pays a fee, independent of whether they own media-receiving devices, and

3. Tax out of the general tax revenue.

Singapore abolished the licence fee, and it does not look like we will return to it. Many of the countries in Europe (Iceland, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway) are also moving away from this model.

The second model of excise duty makes each household pay, regardless of whether they own a media device. In Europe, the fee per household varies from around 160 euros (SS$250) in Finland to 325 euros (S$520) in Switzerland. It may be possible to accommodate income differences so that poorer households pay lower fees. A household-based tax, which is regardless of media device, looks unwieldy to implement.

So the third option of a tax promises to be more efficient and would also raise the least heckles among the populace. As Singapore’s tax system is progressive, the general tax model commends itself.

The funding amount

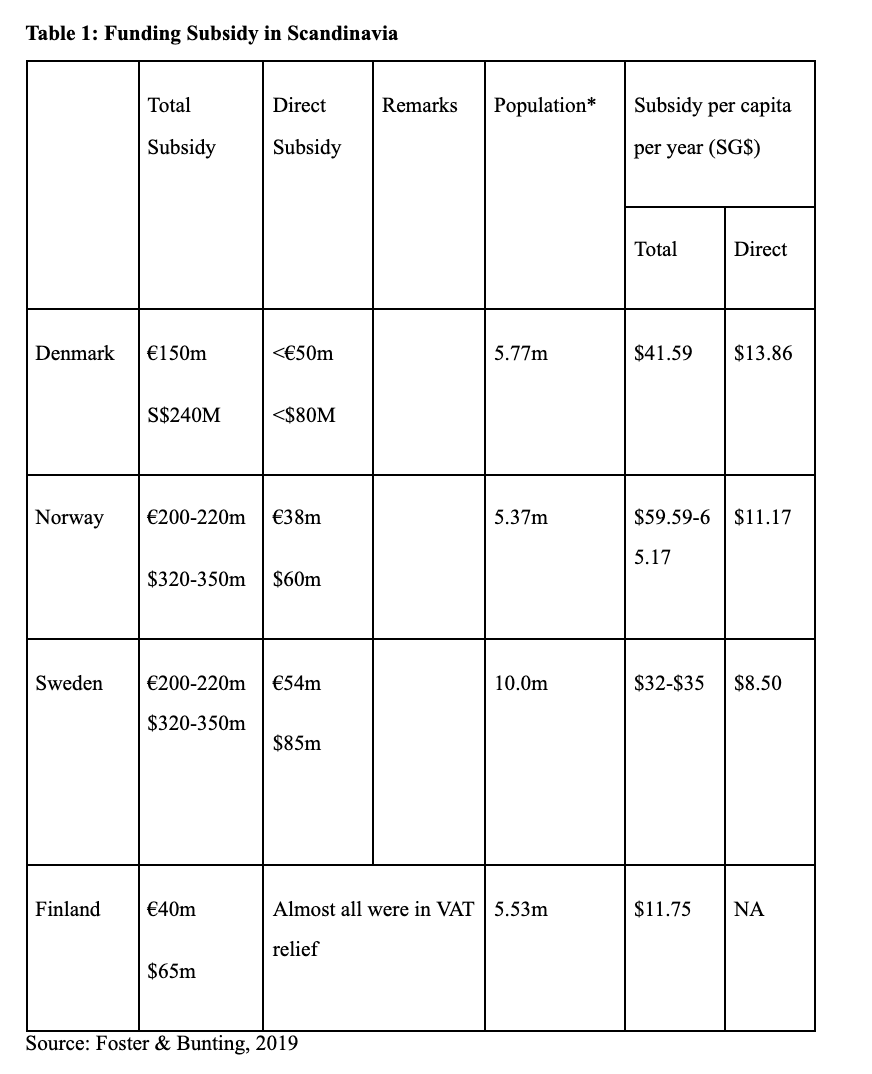

In Scandinavia, a surprising proportion of the subsidy is indirect. That is, the government does not so much give cash as grant waivers and exemptions. Thus, the cash portion varies from a quarter to a third of the total value of the subsidy for three of the countries listed in Table 1.

In Finland — the poorest among the countries listed — the subsidy is mostly in the form of relief from the value-added tax.

As Table 1 also shows, the per capita total subsidy varies from a low of S$11.75 to a high of S$65 This works out to a monthly sum of S$1 to S$5 per man, woman, and child. Sweden, with almost twice of Singapore’s population and therefore a larger media market, manages with S$32-35 a month.

The Singapore per capita subsidy would likely be closer to Denmark and Norway, as their populations (and therefore size of the media market) would be closer to Singapore’s.

* Population estimate from United Nations, 2019. For ease of conversion and comparison to Sing dollar, rates are as of 2021 rates and rounded up.

* Population estimate from United Nations, 2019. For ease of conversion and comparison to Sing dollar, rates are as of 2021 rates and rounded up.

How much should the press subsidy for Singapore be? Taking the average of the total subsidy of Denmark and Norway, because their population is closest to Singapore’s, yields S$280-$295 million or about S$300 million rounded up. It should be noted that this is the total subsidy for all news media. In the Singapore context, it would mean including the portion that is currently given to Mediacorp.

In a 2020 written reply to a Parliamentary question, the Ministry of Communication and Information said that it had allocated S$310 million annually to Mediacorp for the five years preceding. This allocation also included support for entertainment programming, which is not included in the Scandinavian funding support.

Competition rules and other mechanisms

The SPH news cluster will in effect become what is known in the field as a public service media (PSM). (Mediacorp is a PSM.)

Having thriving competition in the commercial space is essential to keep PSM on its toes and to provide audiences with strong domestic choices. Otherwise, readers will continue to turn to other media outlets. Here, the emphasis should be on creating an enabling environment for competition to thrive rather than selective subsidies.

The Scandinavian countries have some form of tax reprieve that is platform neutral to encourage journalism irrespective of medium.

Additionally, there are platform-neutral subsidies for production and innovation that all media organisations are eligible for depending on criteria like the amount of local or regional content journalistic produced, journalists employed and audience reach.

In the Singapore context, it is probably best not to use circulation or reach as the only criterion for eligibility. Just how the subsidy pool is to be carved out will also need further study.

What is clear is this: As news is increasingly consumed online, there should be funding for innovation and production, and possibly entrants, in that space. Support for the media should be platform-neutral. In practice, this means that the subsidy should be extended to the online news space, including online news sites that are currently licensed and accredited.

In the ministerial statement by then-Communications and Information Minister S Iswaran in May 2021, he said that the government will provide funding support for the CLG because “a high-quality and trusted national media, with an instinctive understanding of our national interests and constraints, is essential to Singapore”.

He added that “having such national broadcasters, newspaper publishers, and online news platforms is a public good that benefits the whole of society”.

There should be periodic public surveys to check what the biggest stakeholders, the public, and the audience think of the way money is being spent by the PSM as well as to assess the state of the industry.

Another accountability tool to consider is the Public Values Test that was introduced by the BBC under the Blair government in 2005. The original test was to assess the impact of any new BBC service on the wider market.

For example, a new radio service from the BBC may benefit the public but may reduce advertising income of the commercial radio stations.

The PVT therefore aims to weigh the benefit to the public against the potential damage to the market. When the benefit is deemed to outweigh the damage, the proposal is set out for public consultation and then the governing body of the BBC makes the final decision . The model has been exported to Germany and Norway.

A version of the Public Values Test modified for the Singapore market would assess the state of the news market in Singapore in two aspects: the public benefit and the financial impact on the industry. This ensures that subsidies do not inadvertently destroy a part of the local media market.

The key is to make the news from the PSMs attractive enough to readers. In line with that, there should be institutional checks and balances to mimimise political interference. Besides ensuring that payments are made at arm's length, the Scandinavian rules lock in budgetary provisions for four to five years, which would also facilitate planning.

In Singapore, there is already chatter along the lines of the piper calling the tune; the expectation is that the Government will call the shots when it comes to news coverage because it supports SPH financially.

To continue on that track, however, will turn away subscribers, which then drives down circulation and advertising. This is certainly not SPH’s intention, as Khaw, in his interview, said that he has “urged the newsrooms to set our sights high and focus on growing digital subscriptions aggressively."

The local news industry is not beyond salvation. In the Nordic countries, the PSMs are the gravitational centre of the media landscape, setting the quality standards for the rest of the field. They set the bar to which private commercial media is compared to. The PSMs are in effect an implicit quality control.

There is hope yet for the news in Singapore.

Top photo by Mothership, Google Maps.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.