Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

MOTHERSHIP ESSAY COMPETITION: What does it mean to "sound local" or "speak like a local" in Singapore?

In June, Mothership launched our inaugural essay competition. Over the course of one month, we received around 300 submissions from readers of different ages and backgrounds.

Ivan Maulana was awarded second place, receiving a prize of S$300.

"Ivan's essay reinforced an important truth - that our feelings of rootedness to a society are ultimately not dependent on or reducible to a language or style of speaking."

- Leon Perera, Member of Parliament for Aljunied GRC and entrepreneur

"I like Ivan's use of the story arc technique - beginning and ending with Ah Ma. His mixed-race account of what sounding local means to him is cleverly nuanced with deeper explorations of the Singaporean identity for him as a minority at different levels — race, sexual orientation and age."

- Anthea Ong, social advocate and former-Nominated Member of Parliament

About the author: Maulana is 34-year-old Singaporean who works as a data scientist. He enjoys participating in Singaporean life through volunteering with Waterways Watch Society and Transient Workers Count Too.

In this past month of the pandemic, he has also been sharing his love of National Day songs on a dedicated Instagram page.

By Ivan Maulana

During the late 80’s, whenever my Ah Ma would go shopping with me in her arms, the market folk would coo at my dark skin while joking, "汝按怎抱番仔人的囝 (le an-nua pho hu*n-a lang e kia)". ("How come you're carrying a Malay kid?")

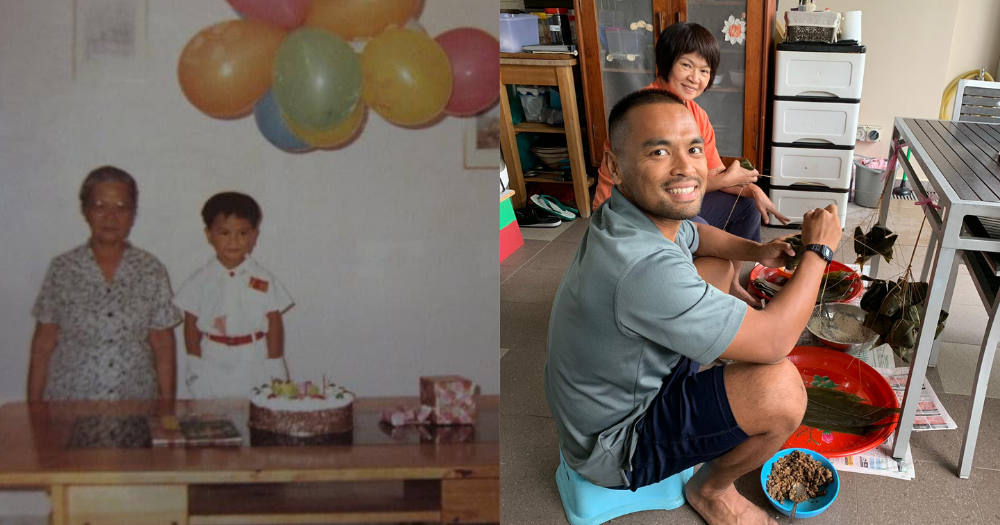

Maulana and his Ah Ma. Photo courtesy of Ivan Maulana.

Maulana and his Ah Ma. Photo courtesy of Ivan Maulana.

The cognitive dissonance they experienced when looking at her skin tone and my appearance still occurs to people I meet more than 30 years later.

I don't fit into other people's ideas of "speaking like a local"

To speak like a local in this island is not just about sounding like a native-speaker of its languages. It also demands that you look the part, because vernacular and ethnicity are deeply intertwined in this city.

Despite my Chinese mother, I do not look Chinese, and despite my love for the language of You Jin and Pan Shou, I do feel alienated when I speak it as my own tongue.

Once, I plucked up the courage to go to a xinyao concert. It is still not clear to me whether people were really glancing at me before the concert started, or whether I was just feeling self-conscious being the only brown person in the crowd. What was clear were the heads turning and the looks of surprise when we all started to sing along with our favourite melodies.

For the rest of the concert, the lyrical poetry of xinyao was accompanied by my neurotic narration of what others could have been thinking: Where did this guy come from? What is he? Wah, Malay also know xinyao.

In fact, I would say, I am not even half-Malay. My father is from Sumatra, with a Javanese and Batak family.

Maulana with his mother and father. Photo courtesy of Ivan Maulana.

Maulana with his mother and father. Photo courtesy of Ivan Maulana.

But that takes so many more words than just saying "I am Malay" to any stranger who deigns to question me about my ethnic identity, before they even know my name.

So I say those three words, hoping the xeno-interrogation ends there, and I remind myself that in any case, Malays, Javanese, and Batak are all from the Nusantara, speaking Bahasa serumpun.

One day a makcik asks me for directions to makam Sharifah Rogayah in Tanjong Pagar, and as I tell her in my Indonesian-accented Malay to follow me, enthusiastic for a chance to show my familiarity with my neighbourhood.

I gently ask about the site's significance to her, and instead of answering, she asks, "Awak dari mana? Bukan orang sini ke?" — "You’re not from here, are you?"

We can connect better without labels like CMIO or “local”

No matter how I change the language I speak or the way I speak, I am not assumed to be "native" in either Mandarin or Bahasa, and it makes me feel so fed up.

But this prescriptive way of equating identity and language does not frustrate only me. I feel a sense of solidarity with others who feel tired living inside the rigid CMIO boxes assigned to us, with its attendant vernaculars and identities that cannot be renegotiated.

Why are so many of us surprised when non-Chinese speak Mandarin or when Peranakans assert their affinity with the Malay language?

Has Singapore lost so much of our complex Nusantara and Nanyang identities that we now struggle with the rich landscape of regional accents?

What is the price of rejecting multilingualism in favour of reductive bilingualism?

A stereotypically bilingual local probably speaks enough Mandarin “for the China market”, together with American-accented English. I am personally guilty of defaulting to a thick American accent in any technical or professional setting, after 10 years of school and work in the U.S., leading to more questions of "are you local?".

Fortunately, this haunting question does not come up when I speak Singlish, because using words like gostan and aiyoh helps smooth over all language cracks among locals.

And yet, what would it mean to look and sound completely local in Singlish but to not have a mainstream Singaporean identity?

Expanding our imagination of local identity

How do I tell my old NS encik that, no, I’m not married with children yet, because my partner and I cannot get married here and we couldn’t both have legal rights for adoptive children here, so we have to leave our home eventually to start a family?

What is the point of sounding like a local if the content is totally alien?

Of course, I could just tell my encik, "Why you so kaypoh?" But I do sincerely look forward to the day when such alternative identities sound completely natural in all Singaporean languages.

I crave a future when our local identity has been stretched to truly accommodate the myriad of configurations of Nusantara and Nanyang languages and accents.

While we’re at it, why not expand our imagination of how locals ought to speak, so that we can each belong comfortably to monolithic groups while also being recognised for our own individuality?

Until that time arrives, I indulge myself in minor acts of language rebellion. I pretend I don’t understand when I don’t want to deal with people. Or listen in on conversations that people think I do not understand.

Each time I get to speak with senior folk, I speak Hokkien and watch their surprise towards this young brown man, then imagine they are the same neighbours cooing over the dark skin of the baby in my late Ah Ma’s arms.

Read our other essay competition winners here:

1st place:

3rd place (tied):

Top photos courtesy of Ivan Maulana.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.