Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

“To us Chettis, there's no difference between Chinese, Indian and Malay. No difference.”

Ponnosamy Kalastree is of Chetti Melaka or Indian Peranakan heritage and takes a lot of pride in being part of this rich culture.

Old image of Chetti Melaka couple. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Old image of Chetti Melaka couple. Image via Alfie Kwa.

When we think of Peranakans, we think of the Nyonya Peranakans.

But not all Peranakans are of Chinese/Malay ancestry. In fact, the word "peranakan" is a broad term for people who are of mixed cultures, descended from interracial marriages between foreign immigrants and natives.

Aside from the Nyonya Peranakans who are of Chinese and Malay/Indonesian heritage, there are the Jawi Peranakans who are of mixed Indian and Malay parentage. And then, of course, there are the Peranakan Indians or Chetti Melaka.

The Chetti Melaka originated from Melaka in the 14th to 15th century when South Indian immigrants arrived on its shores.

The early Tamil Chettis, which means “merchants” in Tamil, married local Malays and Chinese women and had mixed-race children.

Some moved to Singapore in the early 19th century, starting the small yet significant community we see today. This was the beginning of a rich culture, created by the blend of Indian, Malay and Chinese traditions.

A mix of cultures

The Chettis Melakas of Singapore Association used to be invited for annual dinners at Istana, hosted by former President S.R Nathan. Image via Alfie Kwa.

The Chettis Melakas of Singapore Association used to be invited for annual dinners at Istana, hosted by former President S.R Nathan. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Ponnosamy, who prefers to be known as Pono, described Chetti Melaka culture as a three-in-one special — a mix of Indian, Malay and Chinese.

Although ethnically they identify as Indians and practise Hinduism, they follow Malay and Chinese traditions at the same time.

Many even take Malay as their Mother Tongue.

Like many other Chetti Melaka people, Pono grew up celebrating all racial holidays including Hari Raya, Chinese New Year, Deepavali and Christmas.

He also commemorates the Qing Ming festival (Tomb Sweeping Day), only the Chetti Melaka call it Naik Bukit.

Chetti Melaka during Naik Bukit. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Chetti Melaka during Naik Bukit. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Similar to how the Chinese commemorate Qing Ming, the Chetti Melaka respect their ancestors by laying out food offerings and praying at their graves and at home.

Other Chinese elements include the use of traditional long candles for prayers.

Red Chinese candles used during Naik Bukit. Screenshot from CNA YouTube video-Singapore's Peranakan Indians: A Vanishing Culture Revealed.

Red Chinese candles used during Naik Bukit. Screenshot from CNA YouTube video-Singapore's Peranakan Indians: A Vanishing Culture Revealed.

As with many other communities, food is a big part of the Chetti Melaka heritage.

Chetti Melaka dishes are a blend of Indian, Malay and Nonya cuisines that offer delectable delicacies for every occasion.

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association celebrating Chinese New Year. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association celebrating Chinese New Year. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

There is a wide range of Chetti Melaka food but one key ingredient that is common in many dishes is belacan (fermented shrimp paste).

“(For) our food, chilli is automatically mixed,” Pono added.

Other ingredients include serai (lemongrass), lengkuas (galangal), pandan leaf and coconut milk.

Traditional Chetti Melaka favourites include dishes that can be found in other Peranakan cuisines such as ayam buah keluak (a chicken dish cooked with cured seeds from the kepayang tree), ikan parang , ikan sipat masak nanas (salted fish cooked in pineapple coconut curry), and sambal belimbing (starfruit sambal).

Yet, some Chetti Melaka traditions are unique

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

When we first entered his office at Golden Mile Complex, Pono greeted us dressed in his traditional outfit.

Pono in his traditional outfit. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Pono in his traditional outfit. Image via Alfie Kwa.

The Chetti traditional costume, he explained, is heavily influenced by Indian culture, pointing to his scarf which can be found in traditional Indian attire.

And then there was the hat that he wore, called a talapa (headgear). It looked very similar to the songkok, a traditional hat which is commonly worn by Muslim men.

However, the talapa is made from batik cloth and has a distinct triangular feature that rests on the wearer’s forehead.

Chetti Melaka men also wear batik shirts on other occasions.

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Chetti Melaka women, on the other hand, have a greater variety of traditional outfits: the kebaya, cheongsam and sari, depending on the occasion.

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Members from the Chetti Melaka of Singapore association. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

For example, Pono’s wife Dora Woo, a Singaporean Chinese, dons her sari whenever she visits a Hindu temple.

The Chetti Melaka also have their own language, the Chetti Creole, which is a mix of Chinese, Malay and Tamil.

For instance, the Chetti Creole term for “grandmother” is nenek which comes from Malay. However, the words for “grandfather” (thatha) and “uncle” (mama) are taken from Tamil.

While Pono still uses Chetti Creole when conversing with older folks in the community, he lamented that many young people now do not know how to use it.

Used to be confused about his Chetti Melaka upbringing

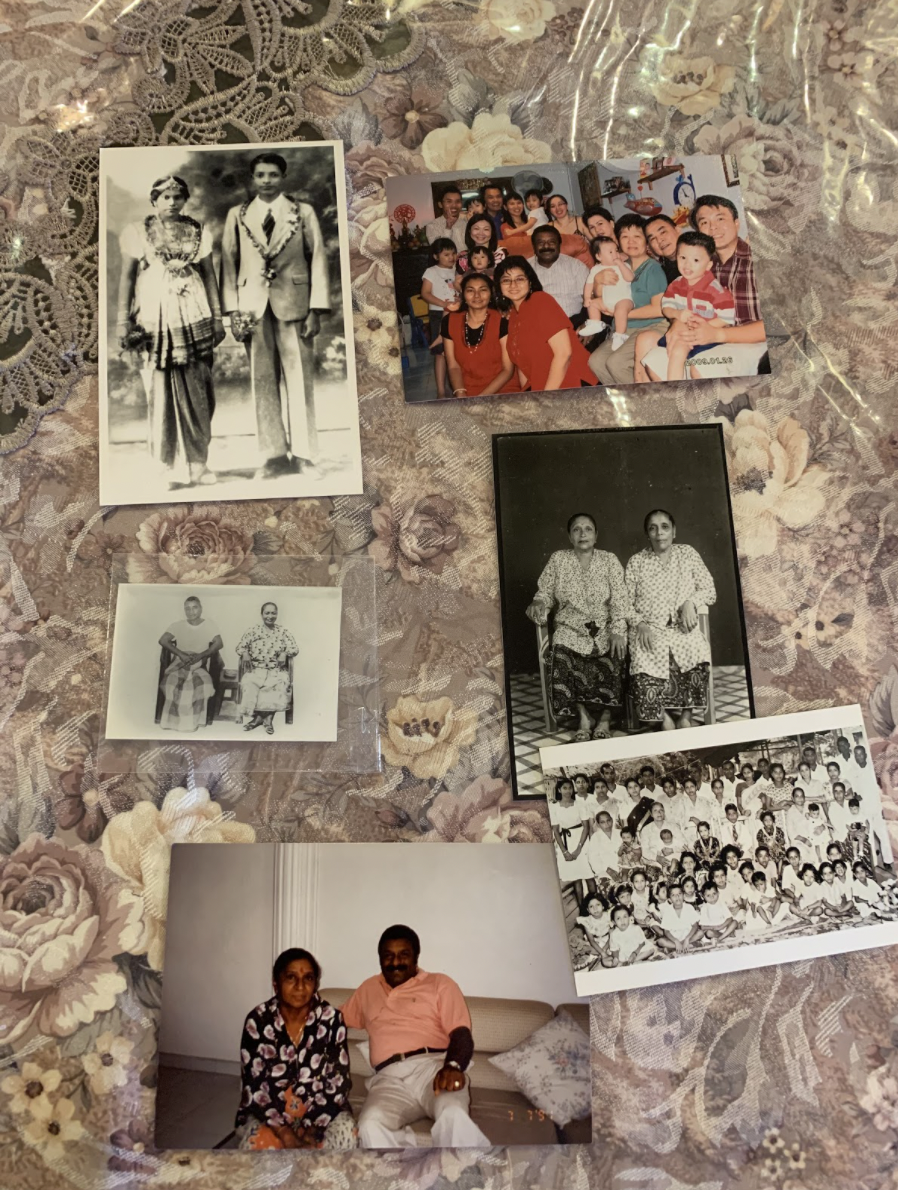

Pono’s collection of photos. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Pono’s collection of photos. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Today, Pono is the president of the Peranakan Indian (Chetty Melaka) Association Singapore and he loves sharing with others about his culture.

However, Pono did not always embrace his culture with such fervour. Pono recalled a time in school when he was unsure of what race he would introduce himself with.

“My name is a very typical Indian name. And you look at me, it's a very typical Indian face... But when you (others) say, ‘you're Indian’, I have to say, I'm Indian, because basically, the Chettis are all Indian.”

Despite being of mixed heritage, he always told people that he was Indian. However, his Indian friends used to make fun of him because he couldn't speak Tamil..

Pono didn’t feel comfortable identifying himself as Malay either, despite speaking the language fluently thanks to his Malay lessons in school.

But over time, he learned to accept and embrace the sheer cultural diversity that is literally his birthright.

Pono, Woo and their two daughters. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Pono, Woo and their two daughters. Image via Alfie Kwa.

“The Chettis adapt very well. ...It’s in our blood already you see, we have already been mixed around,” he chuckled.

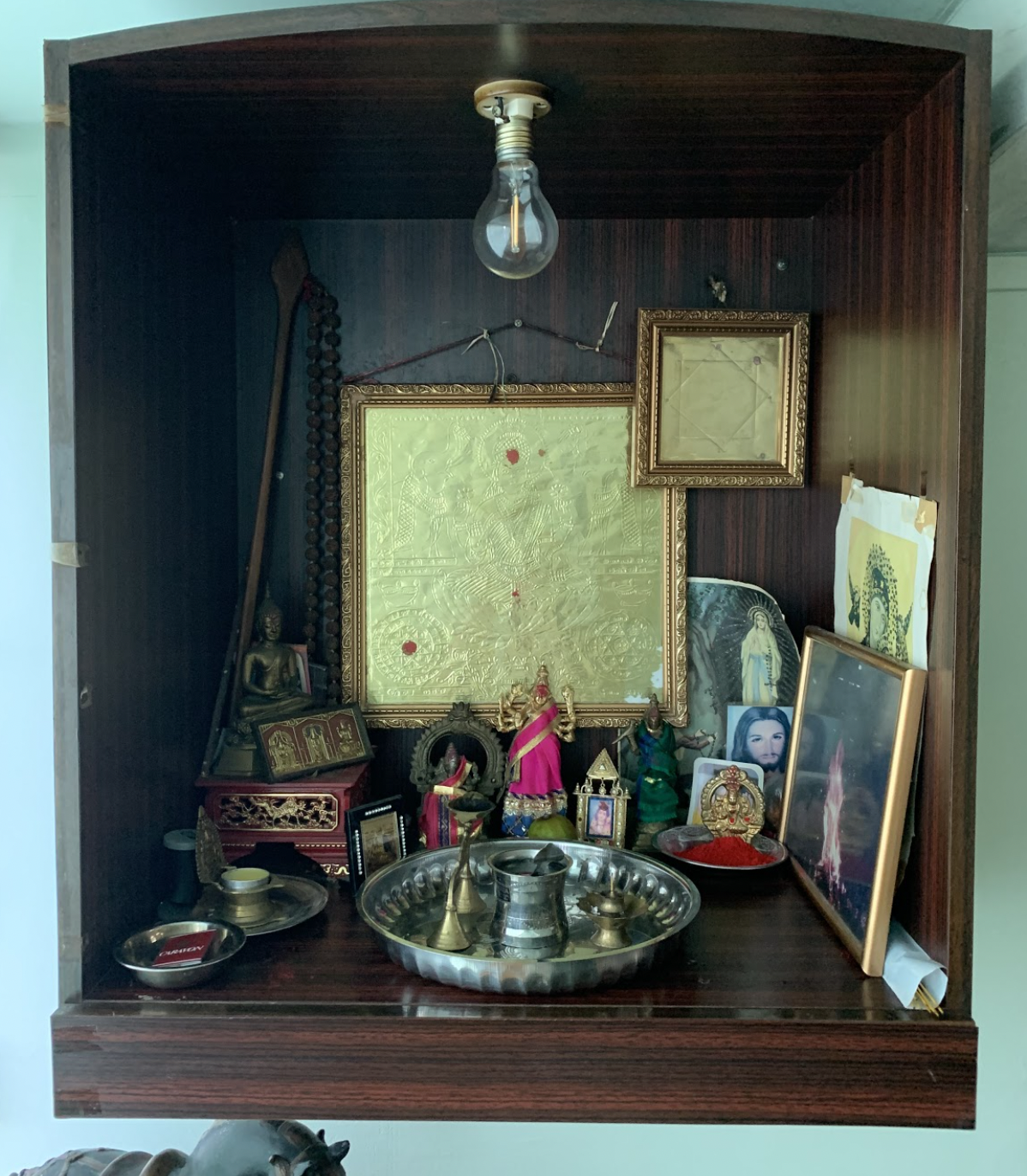

Pono grew up embracing traditions from different cultures and even religions. For instance, although Pono is a Hindu, the altar in his office conference room is a veritable shrine to a multitude of deities like Jesus Christ, Mother Mary, Ganesha, Shiva and Buddha.

He has a similar set-up at home where Buddhist statues and Bible verses co-exist side by side with Hindu deities.

“I was born a Hindu and I'm still a Hindu. She (Woo) is a Buddhist. But we practice both. When you look at my altar, the gods are there, you know, all including even Christianity Jesus. And we go to church, go to a Chinese temple and go to Hindu temple...Doesn't mean that you are a Hindu...you don't care about other religions. We respect all religions. And that is what I mean by Singaporean.”

Family picture with Woo’s side of the family. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Family picture with Woo’s side of the family. Image via Alfie Kwa.

This is why he believes he is more sensitive to other races and religions in Singapore. In fact, Pono thinks that he can be more Chinese than his wife at times.

“Chinese food... I’m all for it,” Pono said, adding that his two favourite local Chinese dishes are chwee kueh and white carrot cake.

Pono, who is clearly a foodie, also gets very excited during the Chinese festivities like the Dragon Boat Festival and Chinese New Year so that he can eat his beloved ba zhang and tang yuan.

“A typical Indian won’t look forward to all this. They don't know (it) in the first place. They just know these are Chinese things. But for us, no.”

Altar in Pono’s conference room. Image via Alfie Kwa

Altar in Pono’s conference room. Image via Alfie Kwa

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Inside Pono's home. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Interracial marriage adds to the richness of culture

In many ways, you might say that Pono is the poster child for interracial marriages. He and Woo have been married for almost 50 years now and they say that the key to a successful marriage is “patience, understanding and tolerance”.

The couple in their living room. Image via Alfie Kwa.

The couple in their living room. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Pono first laid eyes on Woo when he visited the hairdressing salon where she used to work, along Penang Road.

“I suppose it's destiny,” Woo said.

The couple were deeply in love but it wasn’t easy convincing their friends, said Pono:

“There's always some doubt, but they don't really openly criticise and don’t talk to us. But I know, at the back of us, they talk about us like, “why this guy, who is such a nice guy, marry a Chinese girl,” and then her people will say, “why is she getting married to an Indian.” I mean, that is natural.”

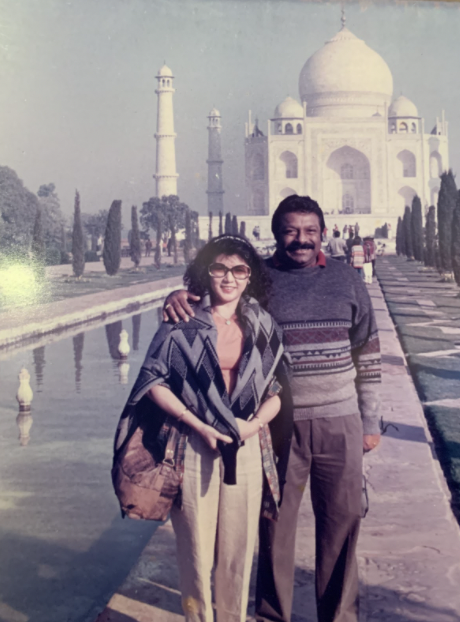

The couple in India. Image via Alfie Kwa.

The couple in India. Image via Alfie Kwa.

But over the years, others saw how the couple grew together by embracing each other’s culture and traditions.

Pono even joked that Woo is lucky to have married a Chetti because she gets to not only learn more about Indian culture but Malay and Chinese cultures too — all cultures packaged into one husband.

Image via Alfie Kwa.

Image via Alfie Kwa.

For almost 50 years, they celebrated and hosted many racial and religious holidays together, inviting friends and family from different cultures, and ultimately, this added to the richness of their own cultures and marriage.

The couple added that despite coming from different cultures, they are fortunate that both they and their families are very adaptable to different races, so they didn't face any family tension when they got married.

Pono added:

“I have some nephews who married Chinese. Always say they need advice so they come to us because we have been (married) a long time.”

Preserving the Chetti culture alive

Pono talking at an event. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Pono talking at an event. Image via Chetti Melaka of Singapore Facebook.

Today, Pono works hard to promote Chetti Melaka culture through the Association of Peranakan Indians (Chitty Melaka) Singapore.

Aside from the usual fundraisers and cultural exhibitions, the association is banking on some rather interesting ways to share its heritage with the general public.

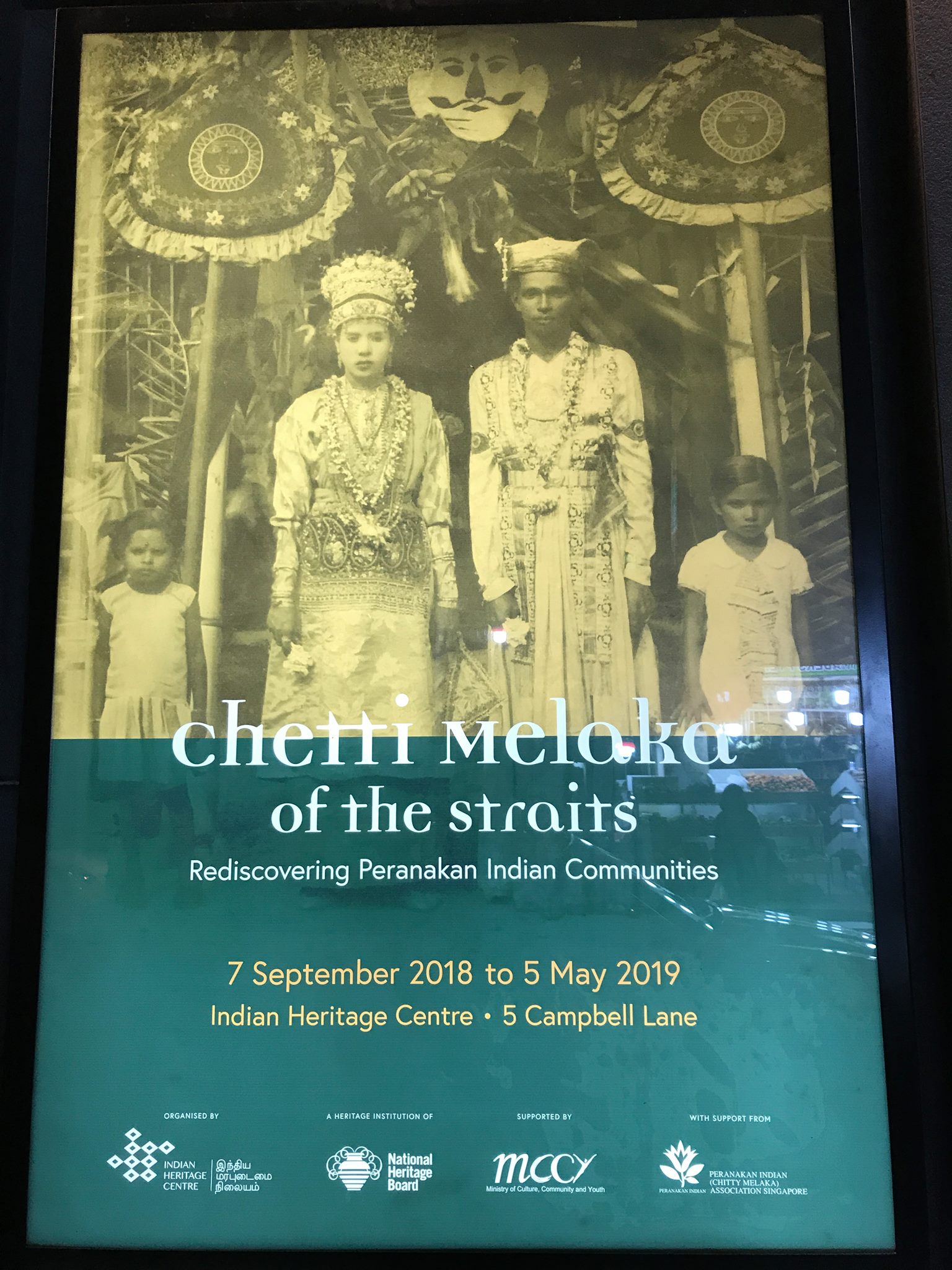

Poster for the Chetti Melaka of the straits exhibition in 2018. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Poster for the Chetti Melaka of the straits exhibition in 2018. Image via Alfie Kwa.

Last year, it released a music album of classic Singapore songs like “Chan Mali Chan”, but in a mix of Tamil, Malay and Chinese languages.

This year, the association is planning to publish a Chetti Melakan cookbook.

Since its founding, the association has made it its mission to preserve this unique culture and heritage.

Pono estimates that there are about 5,000 Chetti Melakans and Indian Peranakans in Singapore. However the association has only 200 members.

Aside from expanding the association’s membership, Pono hopes to find a new generation of passionate leaders who will continue preserving the Chetti Melaka culture in Singapore, passing it down to many generations.

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top images from Alfie Kwa. Quotes were edited for clarity.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.