Sometime back we received a rather mysterious email in our inbox.

The subject line read “Record breaking cycling and freestyle football juggling feats” and while the email’s contents were short, they immediately grabbed my attention:

“Hi,

I finally able to get Eric to verify my record breaking free style football juggling feat possibly a world record in 1986 at Woodsville Secondary School.

Kindly send your earlier reply, thanks

Rgds,

Henry Leong Him Woh”

Needless to say, I was intrigued.

I shot an email back to Leong asking for more details.

He replied with not one, but two rather incredible undertakings.

The first was encapsulated in a long running sentence, each clause adding to the impressiveness of the singular feat:

“I was cycling on the grass, using only one leg, handsfree, and at the same time carrying another bicycle while zigzagging between metal poles.”

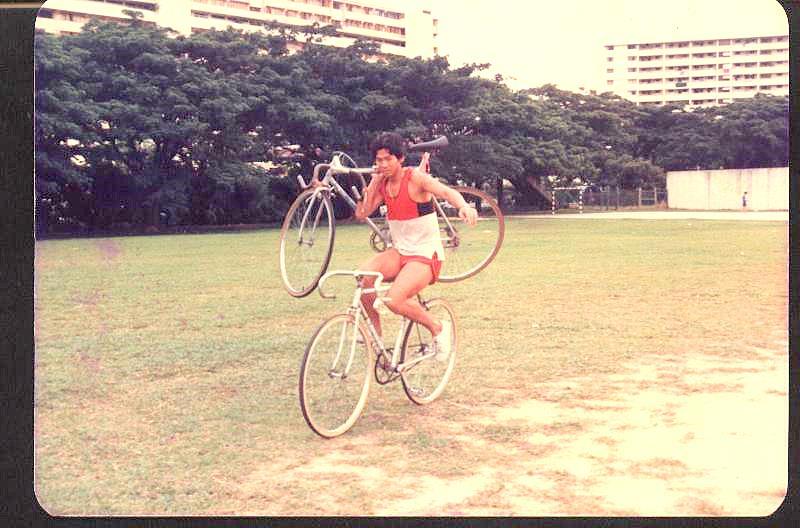

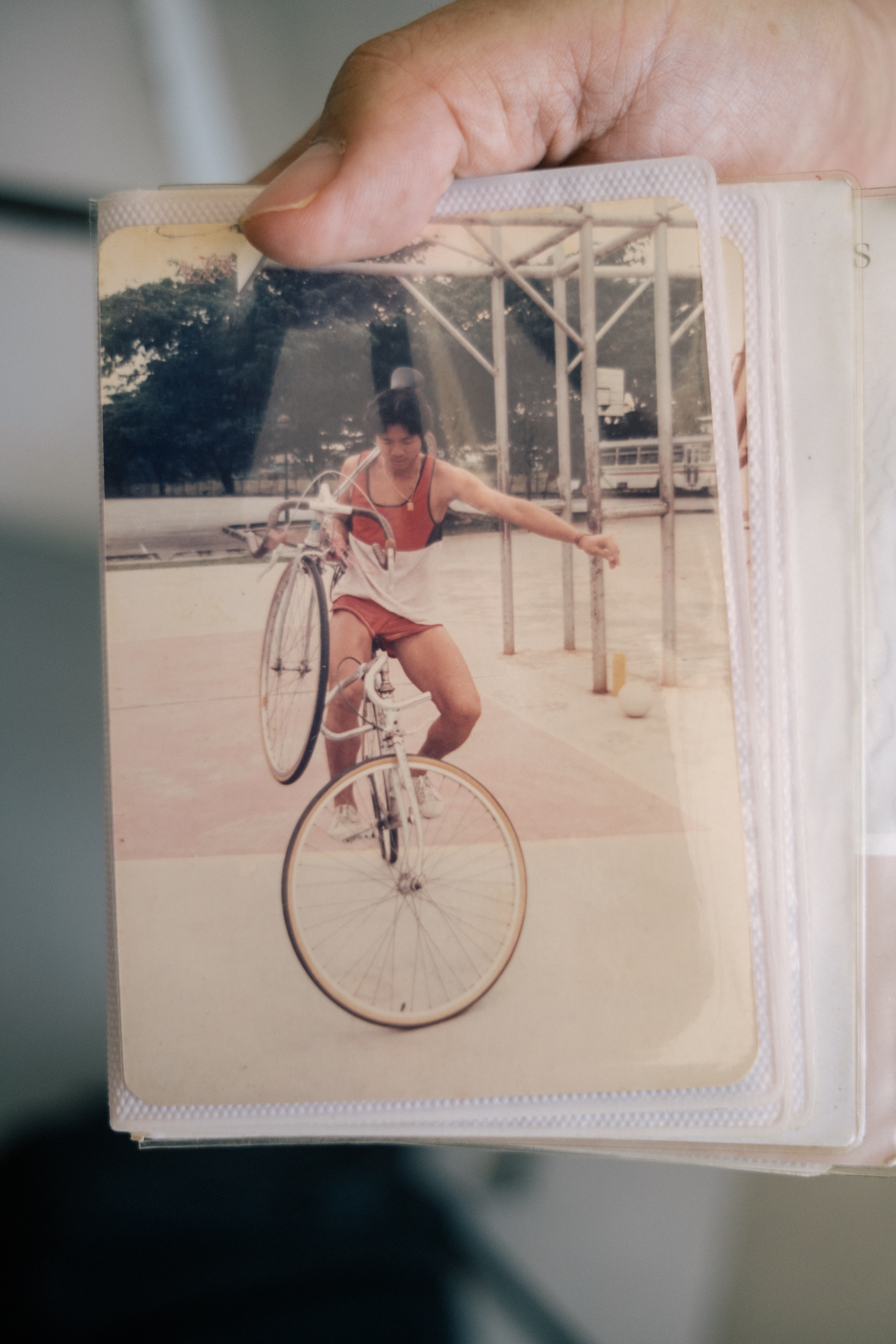

Leong's email to me included this photograph of him performing a cycling stunt. Image courtesy of Henry Leong

Leong's email to me included this photograph of him performing a cycling stunt. Image courtesy of Henry Leong

Yet as spectacular as this was, it was a totally different show of skill that Leong believed might be a world record.

It involved juggling a football for one hour and 20 minutes, non-stop; using his feet, thighs, head, shoulder, and chest, Leong claimed to have juggled the ball 3,400 times on that aforementioned occasion at Woodsville Secondary School in 1986.

He asked me if I could help him get the record certified and I said I would — but if only I could verify that he had actually performed the spectacular feats as he described.

And that’s how I came to be seated across from an enigmatic 60-year-old man at a cafe in Lavender.

Growing up in poverty

As we sat down for drinks, Leong told me about his upbringing, which he described as steeped in the squalor of absolute poverty.

After his father's untimely death, Leong’s mother had no choice but to shoulder the responsibility of looking after her young family.

Partially aided by social welfare, she took to making and selling glutinous rice and yam cakes.

Leong — who was five at the time of his father’s death — and his siblings squeezed into a one-room rental flat near Mattar Road.

“Many times we have only dark sauces and white rice for our meals,” he recalled with wide-eyed intensity.

Due to space constraints, he would wait till all the neighbours had gone to bed each night, before quietly dragging pieces of cardboard out of the house and into the common corridor to sleep.

By 4am, Leong would have to get up to help his mother transport her home cooked fare to the family’s stall. He did so on a sort of tricycle-cart hybrid.

“I loaded the tricycle with all these heavy foods — at least four tins, glutinous, yam cakes, bee hoon. My mother would sit behind and I would cycle from Mattar Road to Sims Drive.”

After unloading everything, Leong cycled to school, before returning in the afternoon to pick up his mother; “repeat 364 days except Chinese New Year,” he said.

“I needed to do all this heavy duty work to help feed my family.”

The Will to Win

Well aware of his family’s troubles, Leong developed a voracious appetite for reading, hoping that he would find a solution to their predicament in biographies of individuals who had achieved great things.

On Wednesdays, a mobile library set up shop at MacPherson Community Centre, and Leong would be there tearing through whatever books he could get his hands on.

However, none seemed to capture his imagination like a book The Will to Win, which detailed the lives of notable Olympic athletes.

As he turned the pages of the book, Leong began to dream of a future apart from hardships and financial strain.

All he needed was the mettle to make it happen.

“I was inspired by all these Olympic champions," Leong told me.

"They overcame great odds. Many trained up to five hours a day because they wanted to be world champions.”

And so Leong was determined to follow in their footsteps; he was already spending a lot of his free time on the football pitch with his friends, and decided that he would pursue it as a means of becoming great.

Leong invented a simple contraption to hone his juggling skills. Image by Andrew Koay

Leong invented a simple contraption to hone his juggling skills. Image by Andrew Koay

Exchanging soccer for stunts

However, by the time Janice Seah from The Straits Times interviewed a 23-year-old Leong in 1985, his ambitions had taken a significant hit.

Seah wrote a column for the national broadsheet called “Seen and Heard”, which she described as being very “light-hearted”.

“Basically (the column) profiled any kind of sports-related personalities or events. The quirkier the better,” Seah said to me over a video call.

“The more interesting, the more left-field, the more quirky the story was, the more fun it became.

Henry fit the bill.”

Sometime prior, he had tried to join a football team in Geylang, but after being injured by his teammates during training, Leong decided the rough and tumble of the professional game wasn’t for him.

“Instead, he’s learned to juggle the ball,” wrote Seah in 1985.

The stunts Leong turned to — juggling and cycling — were much safer and kinder to his body, even while serving as avenues for his pursuit of greatness.

Leong would practice his juggling skills for up to four hours each day at the now-defunct Woodsville Secondary School.

He credited his long hours riding back and forth on the family's tricycle-cart (with its heavy loads and all) as the reason why he had the strength required to pull off his one-legged cycling.

Evidently, while he was no longer pursuing his dream of becoming a football star, his prowess at these new endeavours had earned Leong some recognition, at least in the local paper.

While Seah can’t remember exactly how she came to hear of Leong, she told me she’d likely received a tip-off from a Singapore football official who told her about “a boy who was keen on soccer and was trying all sorts of tricks and everything”.

Making his mark

Leong at 23, was something of a loner, said Seah.

She remembered a young adult who seemed troubled by issues related to his family, who saw soccer and his stunts as an escape from what he was going through.

“He was not so much shy as he was very reserved,” recalled Seah.

“But when he started to talk about his passions and when he started to talk about all these things that he was doing, he did become very animated and he did become very enthusiastic."

Yet, not everyone shared Leong’s eagerness. Seah said Leong’s family was less than supportive.

"He was off on this quest of his… I think it was just something that he found he was good at and he enjoyed it. I think he felt, ‘I would like to be able to make a mark.’”

Not long after he made an appearance in The Straits Times, Leong was featured in a 1986 episode of Channel 5’s “World of Sports”.

A TV crew filmed Leong performing his feats at several locations across Singapore, and the footage was cut into a segment that played on a Sunday at 10am.

The boy who grew up in poverty was finally starting to get national attention.

According to Leong, it was only a few months after the episode aired that he performed his potentially world record-breaking freestyle footballing juggling attempt at Woodsville Secondary School in front of hundreds of onlooking students.

Leong mastered the skill of riding a bicycle handsfree, while carrying another bicycle. Image by Andrew Koay

Leong mastered the skill of riding a bicycle handsfree, while carrying another bicycle. Image by Andrew Koay

Eric, Francis, and the search for evidence

But did he actually set a world record?

Before we get to that question it’s worth exploring if in fact, the feat actually went down as Leong described.

In his first email to us, Leong had dropped the name “Eric” without much context. Eric, he had written, would verify his record.

It turned out that Eric was a friend of Leong’s back in the day.

Having met on the football pitch, the pair would play for hours on end, often till it got too dark to see the ball. Then Leong, Eric, and whoever else had been kicking the ball around would head to a nearby coffee shop to continue hanging out.

Naturally, Eric was also there at Woodsville Secondary School when Leong juggled the ball for an hour and twenty minutes straight.

Yet, Leong described their present relationship as very hot and cold, with the friends falling out at various points through the years.

Sometime in late 2020, the pair reunited, and it was there, in front of another friend named Francis, that Eric apparently agreed to testify that he'd seen Leong perform his potentially world record feat.

This gave the now-60-year-old Leong renewed impetus to get his juggling stunt verified.

“He saw the whole process from the beginning to the end,” said Leong.

“It was a major breakthrough.”

The only problem? Eric wasn’t keen on speaking to me or vouching for Leong.

I was shown messages where Eric let Leong know, in no uncertain terms, that he would not be speaking to the media on the latter’s behalf.

Then there was Francis, mentioned above as having been there not when Leong juggled the ball for an hour and twenty minutes, but at the recent meeting between friends.

An old football kaki of Leong and Eric’s, Francis had purportedly witnessed Eric professing to have witnessed Leong’s feat.

I know how ridiculous this sounds, but if Eric wouldn’t vouch for Leong, perhaps Francis could, in a convoluted third-hand sort of way.

Francis also seemed much more open to talking, so we arranged a time to speak.

But come the day of our appointment, Francis didn’t reply my messages and didn’t return any of my calls; he ghosted me.

“He has always refused to verify for me,” said Leong on Eric.

“They (Eric and Francis) prefer to keep a low profile.”

Trying and failing to verify the record

As far as I can tell, Leong has made several bungled attempts to have his 1986 feat recognised through the years.

Not long after that day at Woodsville Secondary, he wrote in to the Guinness Book of World Records.

Their correspondence, which was a long and drawn out affair over snail mail, eventually culminated in the international record keeping authority telling Leong he would need to redo the stunt, this time in the presence of an adjudicator.

However, Leong didn’t fancy the new conditions, which would have required him to take a five-minute rest after every hour of juggling.

To Leong, this would have diminished the grandeur of his achievement.

“My type is skills type,” he said to me.

Eventually, Leong’s mid-twenties arrived and as he started working — as a printer for Singapore Press Holdings — he found himself too busy to keep up his training regime and world record attempts.

He did, however, pop up every now and then to try and get his 1986 feat certified.

One avenue he pursued was our own local version of the Guinness Book of World Records, the Singapore Book of Records (SBOR).

But when I spoke to Ong Eng Huat, president and founder of SBOR, it seemed Leong’s chances, 35 years on, are bleak.

Ong said that to have a record certified, an individual needed to have it witnessed by an independent adjudicator provided by SBOR.

The organisation is also willing to give special dispensation to records set before its founding in 2005, but in those cases, they would need evidence of the stunt’s completion.

Unfortunately for Leong, both then and now, his evidence is insufficient.

Ong was familiar with Leong, but reluctant to comment on him.

And while the online version of the Singapore Book of Records did not have a freestyle football juggling entry, Ong told me that he vaguely recalled the local record being held by a pair of South Korean jugglers.

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

Hopes dashed

Nevertheless, any hope Leong might have had of being a current holder of the record was dashed when I went searching through the news archives for articles on record-setting juggling.

In 2005, John Taylor, a co-founder of SBOR had written into Today — in reply to a query from Leong published the week before — to say that the national record for freestyle football juggling was 7,500.

Some months after, in 2006, Today published an interview with Leong where he appealed for witnesses to write in and affirm his claims.

There were hundreds of students present at Woodsville Secondary School that afternoon. Surely one of them would remember?

Then 45 years old and a good 20 years after the fact, Leong said:

“I know lots of people have done bigger and better stunts, but I don’t care. I just want to know, was it a record when I did it in 1986?”

“Hardly you’d see people juggle for that long.”

I did manage to find one person who believed that Leong could've set a record back in 1986.

Mark Tay, one of Leong’s friends who was willing to speak to me, said that while he wasn’t there on that specific day in 1986, he often played football with Leong and knew what he was capable of.

Tay, 48, was a student at Woodsville Secondary School and the football team he was a part of as a teenager would use the school’s field for its training on the weekend.

“We would play soccer every time, you know, and he’ll be there and he’ll start juggling his ball,” said Tay.

“So we are looking at him juggling and we asked him do you want to play soccer with us?”

And while Tay doesn’t remember Leong being an outstanding football player, he does remember his amazing juggling skills.

“Yes, it could have been a national record,” he said, on Leong’s attempt.

“Hardly you’d see people juggle for that long.”

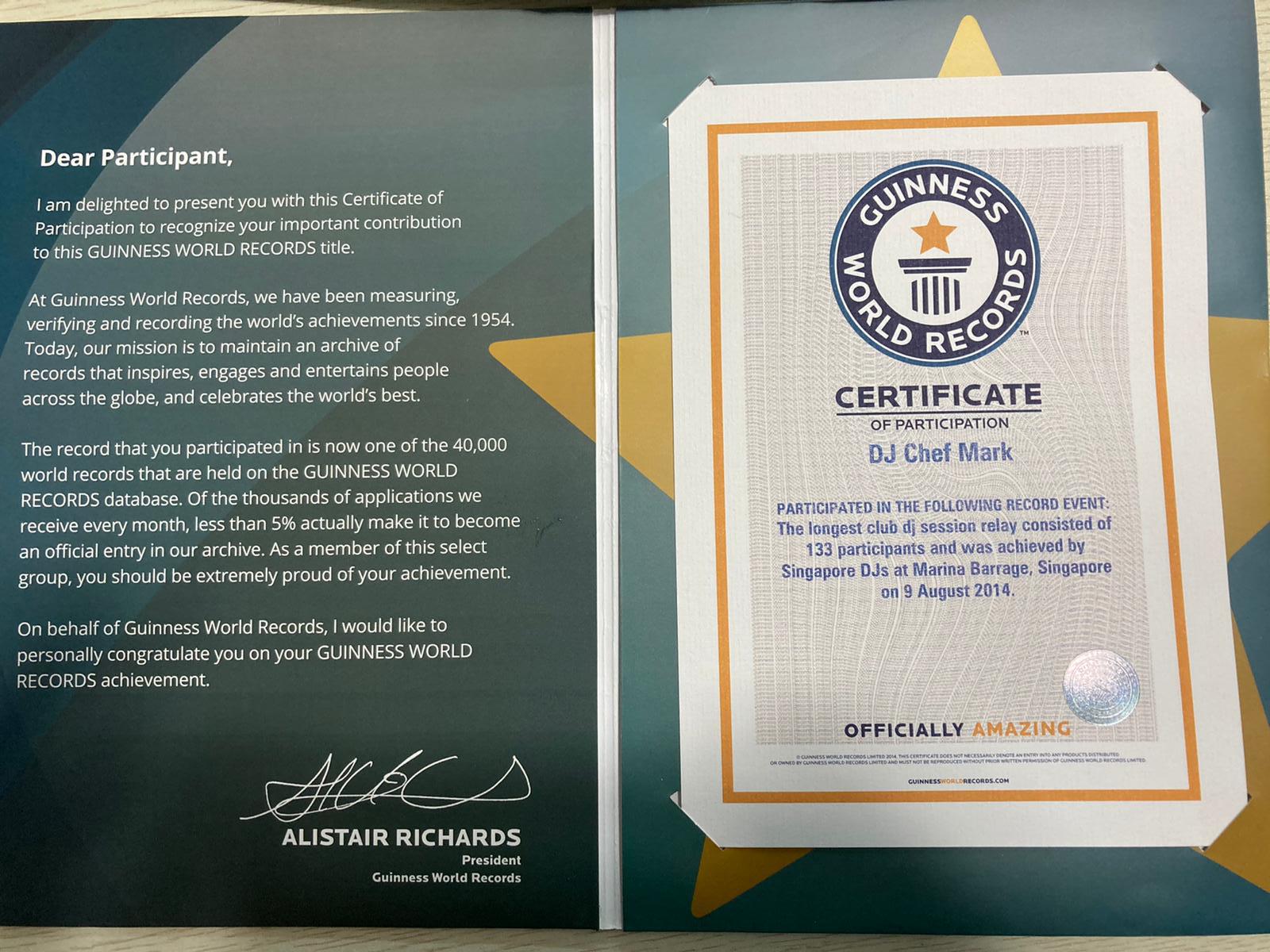

Somewhat coincidentally, Tay happens to be a world record holder himself.

These days he's an accomplished chef in Japanese, French, and Italian cuisine.

He even placed in the world's top ten in the inaugural Washoku World Challenge, a Japanese food competition held in 2013.

But perhaps Tay is most proud of holding the world record for the longest club DJ session relay.

Mark Tay was declared "officially amazing" after he was part of a successful world record attempt. Image courtesy of Mark Tay

Mark Tay was declared "officially amazing" after he was part of a successful world record attempt. Image courtesy of Mark Tay

Along with 132 other participants, DJ Chef Mark — as he is referred to on his Guinness Book of World Record's certificate — managed to create one long mix, each DJ contributing one song to the five-hour effort.

He was, according to the international record keeping body, "officially amazing".

When I asked him if the record still held importance in his life, Tay chuckled.

"Of course," he said.

"To me, I'm not educated. I'm only Primary Six educated, but certain things that I've achieved in my life, I think its good enough for my kids to learn."

"That day it was my peak form"

My last meeting with Leong was at his HDB flat. He was reluctant to speak there, so we found a quiet spot in the common corridor.

His eyes characteristically burst into life as he recalled that fateful day at Woodsville Secondary School.

It would have been around 11am, after he'd finished helping his mother at work. Eric, who was in the military, was finishing work as well.

The pair headed to the field at Woodsville Secondary as they often did, where students were in between classes and were walking through the field in large numbers.

He started with his usual routine which he had performed for the media in the past.

It involved controlling the ball with various parts of his body 200 times.

But when that routine came to an end, for some reason unknown to Leong till this day, he continued juggling.

"That day it was my peak form," said Leong, adding that he was almost surprised at how long he had managed to keep the ball up in the air.

Finally after an hour and twenty minutes, with the count at 3,400 juggles, Leong finally dropped the ball.

"I felt amazed by my feat."

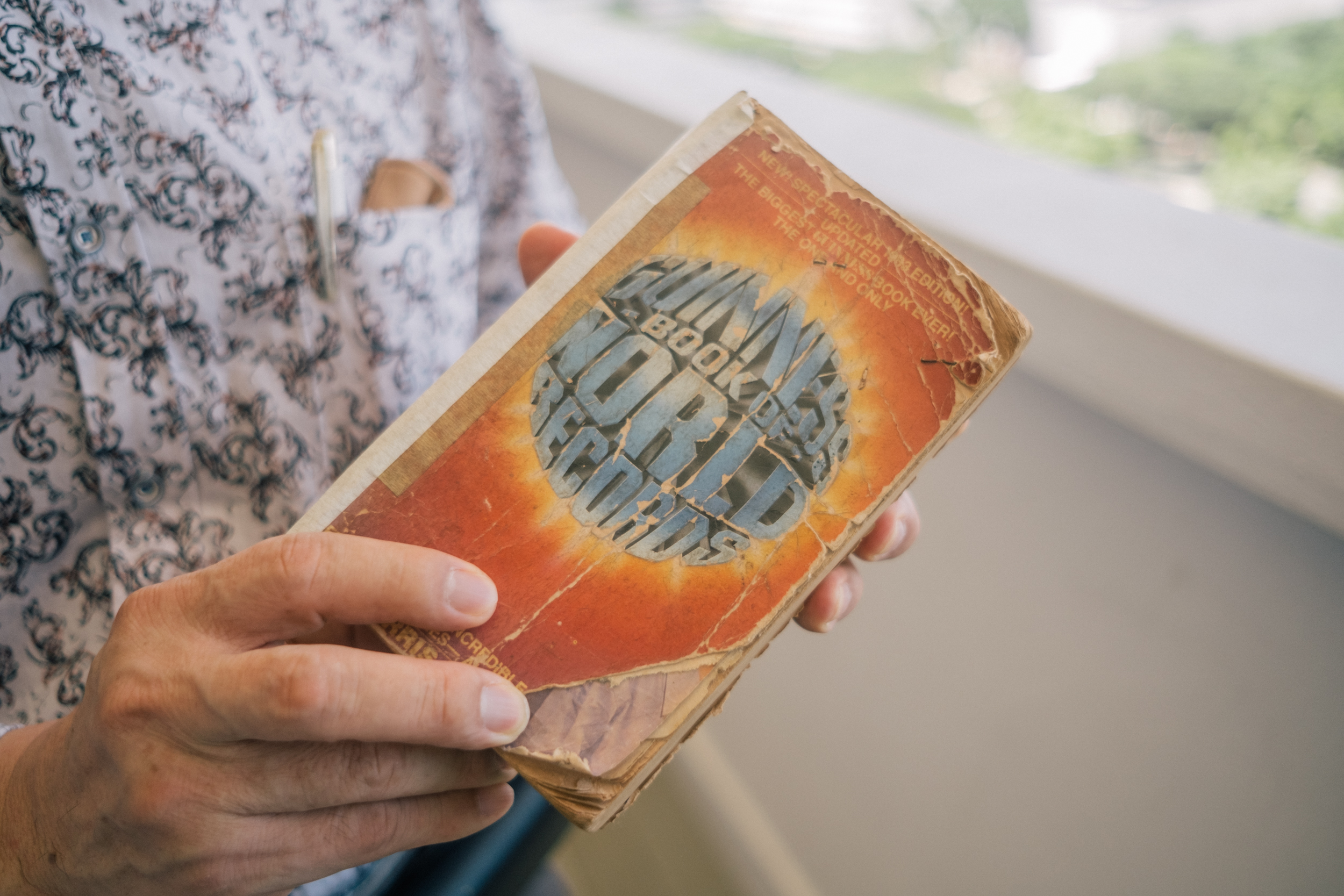

Leong's 1993 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records is torn and tattered, but precious. Image by Andrew Koay

Leong's 1993 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records is torn and tattered, but precious. Image by Andrew Koay

Memoirs of the past

From inside a large plastic bag that Leong had with him during our interview, the 60-year-old pulled out a football.

It was bound by a net and rubber bands that he had tied together, suspending the ball.

He explained how this simple contraption, of his own invention, allowed him to master his juggling skills.

Then, he pulled out his 1993 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records.

It was torn and tattered, with its yellowed pages held together by multiple layers of tape.

Inside the book, Leong had stapled newspaper clippings of other record-breaking feats through the years.

There was something poignant about watching him turn the fragile pages, pointing out different records that he was impressed by.

The search for greatness

When I told Leong that from my research, it seemed unlikely that his 1986 attempt would ever be included alongside those records, he seemed unperturbed.

"It's still important to me."

"I hope I can encourage my sons when they sees it," he said, referring to his boys aged 16 and 21.

But more than that, Leong just wants to definitively say, beyond a shadow of doubt, that he had achieved something great.

"Sometimes when I talk to people, from the look on their face... you know?"

So did Leong really do it? Did he really juggle the ball 3,400 times with his feet, thighs, head, shoulder, and chest for an hour and 20 minutes?

I can’t say I've uncovered any concrete evidence, but I can say that he's made a believer out of me.

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top image by Andrew Koay and courtesy of Henry Leong

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.