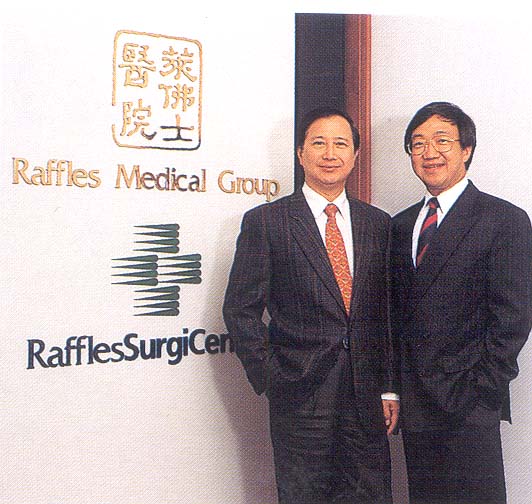

On the day I met Dr Loo Choon Yong and Dr Alfred Loh at Raffles Hospital, I asked them if I could take a picture of them together.

It wasn't entirely straightforward, doing this — Loo, as executive chairman, is a very busy man with barely 15 minutes between meetings — but when Loo and Loh came together, the former's mischievous grin snuck an appearance, while the latter's serene countenance took on a more relaxed tinge as the two wondered aloud when the last time they took a photo together was.

"Was it that long ago? Nah, it was when our longtime patient came by last month to visit and we took a photo, remember?" Judging from their uncertainty, it could well be that their last photograph together was this one, back in 1995:

Loh and Loo back in 1995, at the opening of Raffles Surgicentre. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Loh and Loo back in 1995, at the opening of Raffles Surgicentre. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

What's a surgicentre, you might ask? It's one of the concepts the two came up with at the time, bringing together the specialists they trusted and would refer their patients to for surgeries, and the demand for "day hospitals" — where short, less-invasive procedures could be performed.

Sure enough, Loo says, they would run out of space at their first surgicentre within nine months. And it would be their collective desire to do more for their patients that led them to establishing and building Raffles Hospital, the iconic building in Bugis.

Which, in turn, propelled what Loo still calls a "practice" into Singapore's largest homegrown privately-owned medical group, this year turning 45 years old.

So how'd Loo and Loh get the two-clinic practice they bought over from a retiring doctor in Chinatown to the heights Raffles Medical Group has scaled, and remain good friends through it all?

To find the answer to this, we track back to the year 1968, when they first met standing over the same cadaver in medical school.

The "armchair anatomists"

Loo (left) and Loh (right) at their graduation from NUS medical school in 1973. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Loo (left) and Loh (right) at their graduation from NUS medical school in 1973. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Back in those days, both explain, the students spent their days on common schedules, starting with 8am lectures, dissections on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, followed by clinical placements at hospitals in the afternoons that can stretch to nighttime.

Loh shares how this helped him to understand Loo's idiosyncrasies quite quickly:

"Because in university, they group you according to your surnames. So he's Loo, I'm Loh. So during the preclinical years when we were doing experiments, cadaver dissection, we were always together. Then even after that when we were doing clinicals, where we were posted to the various hospitals for clinicals, we were together. And in KK, for example, where we had to stay in the hostel, because again, our names are next to each other, we shared the same room. So he and I were practically, you know, like, joint twins."

While Loo spoke of their cadaver sessions even more jovially:

"We were all friends. Because you meet each other, that dissection group you are seeing each other, you're laughing, joking the whole morning. So three mornings a week, that's quite intense. And of course, we always say, the one who dissected the most, he ended up as an orthopaedic surgeon. Another one became a heart surgeon. The rest of us actually didn't dissect — we were all laughing, entertaining each other, joking; all armchair anatomists, we called ourselves."

With all the time the boys spent together, they agreed also that in post-graduation, if they were to leave their respective jobs to start their own practice — Loo was offered a traineeship in general surgery at the time, while Loh was two and a half years into a three-year paediatrician course in private practice — they would do so together.

S'pore healthcare in the 1970s: people selling signed vaccination certificates, reused needles and syringes

Which brings us to how Raffles Medical Group came to be.

Loh recounts how their shared time spent in clinical placement at government hospitals allowed them to observe how doctors practised and how their patients responded; they also picked up each other's personal feelings in response to what they were seeing, and found that they were forming similar opinions about the state of things in Singapore's healthcare at the time.

For what I quickly learned would be the source of classic in-your-face bluntness, I turned to Loo, who shared a couple of ghastly examples:

"People were selling vaccination certificates, for instance... and they were selling books of these, they sign and give it, sell it to the travel agents, who then resold the certificates.

And then one day, there was an investigation, many practices got affected, got fined and all that. There are many other practices that were not in conformity with professional and ethical standards."

One trigger for him as a young doctor in the 1970s was also the observation that it was common practice — among government hospital doctors — for doctors and nurses to recycle the needles they used.

These needles were washed and autoclaved (an industrial steam sterilising process), but still... reused.

"The whole world didn't know about Hepatitis. We knew about Hepatitis A. We didn't know about Hepatitis B, C and so on. You must remember I'm so old right, I'm talking about the 1970s — 40 odd years ago, almost 50 years ago.

So I say we already suspected the livers get infections. How can we (be doing) this?? So I used to use my own salary to buy (new needles), I go on duty. I have no heart to prick (with recycled needles). I bought my own needles and my own Venojet. I cannot use recycled needles, knowing."

After awhile, Loo said he started asking the aunties who wanted to give him gifts of gratitude for curing their babies of jaundice to instead buy needles for him so he could use sterile, single-use needles for every single patient he saw.

"And then after a few months I said the longer I do this, how can I compensate for a whole population? And then what made it worse was the fact that some people were getting medals for being 'efficient'... I said what is this?? This is misallocation of resources!

So I said no lah, I don't want to be part of this system. So that's how Raffles started. 'Come, Alfred, we have a group of doctors work together to look after a group of patients, a group of patients who trust us, who will pay us costs plus a bit of margin.' That's how we started. The story 45 years ago and today is the same story of the why."

A marathon five-hour meeting on a concrete bench at an HDB void deck

Loo's pithy statement to Loh is a quick summary of what was in reality, as Loh relates, a five-hour nighttime meeting the two men had at the foot of the housing board block Loh lived in with his family.

"So one evening he came over to my place. We went downstairs by the carpark, sat on the cement seat and discussed this issue about starting the practice from about 9 something till about two in the morning. And that's where we laid foundations of the relationship and how we would proceed from practising.

And it was just with a handshake, that we'd agreed that we'd be partners and that we agreed along certain lines, how we would work together. There was no paper, no signing of nothing. So that to a certain extent having lasted almost 50 years tells you the depth of relationship that we have."

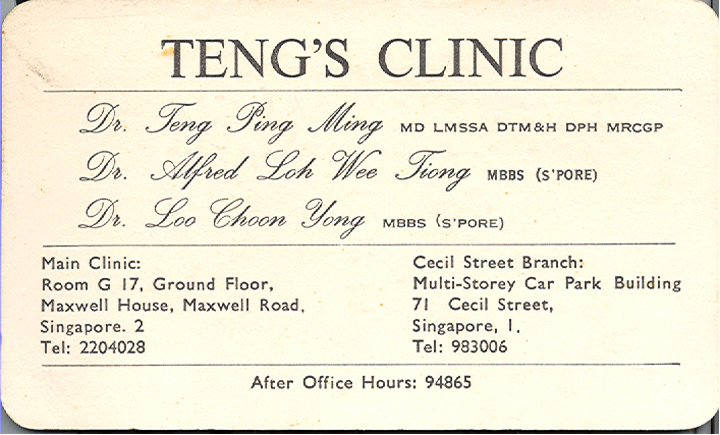

Loo and Loh's first foray into their 'own' private practice — joining up with the retiring Dr Teng. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Loo and Loh's first foray into their 'own' private practice — joining up with the retiring Dr Teng. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

And before they knew it, the opportunity came for them to get started — an elderly doctor managing two clinics in Maxwell Road and Cecil Street was looking for someone to take over his practice so he could migrate to Canada to live with his son.

Loh learned about the opportunity through his father-in-law, who happened to know Dr Teng Ping Ming, and soon he and Loo were on board, each taking one clinic.

"But you know, it was not easy. Because the old gentleman, Dr Teng, he was a kingpin in Chinatown at that time, you know, his patients were old towkays in Chinatown. And he was at that time already in his... almost like me, grey hair in his 70s already. We were about 28?

So I took over the clinic he was running in Maxwell. And there were occasions where a patient will come in, open the door, look at me, close the door, and tell the nurse outside, 'I don't want to see a baby doctor'. In Hokkien they say 'ginna lokun' — in other words you're a young punk, you're inexperienced, I don't want to see you. So we had to go through that."

Building an 'invisible' brand of quality, dedicated practice

But it was through this that Loo and Loh became determined to pioneer a style of medical practice not done at all in Singapore — this was a time where doctors in the heartlands saw more than a hundred patients a day, for no more than two or three minutes each.

"He and I agreed that we ought to go into practice in a less hurried way — we wanted to give patients the satisfaction of knowing what they have, and giving them the necessary advice, not the one see and then within two minutes, you're out.

So we started with the premise that if you give patients enough attention, enough patient education, enough information about their welfare, they will look after themselves. And that was, I think, one of the cornerstones of our practice."

Loh observed that people started telling others about the young doctors in Chinatown and how dedicated they were in their service, and would also bring their relatives, friends and colleagues back to him and Loo for consultation.

As they started hiring new doctors to join them to manage their growing patient load, teaching them to work by the axiom "Treat your patient well and your patient will treat you well", Loh says they got their new colleagues to sit in on consultations with them for their first week in order to learn how they do it.

"And that's how we built our practice. That's how we built our reputation. We were not cheap — in those early days, we were known to be not cheap — but patients were prepared to pay because they wanted that sort of service."

How to capture the lucrative market segments

Setting up the Straits Trading Clinic to serve corporate clients in 1982. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Setting up the Straits Trading Clinic to serve corporate clients in 1982. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Loh explains another two key ways in which they were successful in capturing business from big spenders:

- pre-employment health checkups, and

- health checkups for foreign patients from around the region.

On the former, the two doctors realised that other private practices in the central business district catered to companies that would send their employees to them for pre-employment checkups — but the process was long and tedious and involved plenty of back-and-forth and outsourcing to labs and facilities in Orchard Road.

"We realised that in those days when companies were recruiting because our economy was picking up, we found that actually economy of time was more than important than the economy of dollars.

Companies were prepared to pay extra if you can turn around the checkups for them more quickly. So because of that, we reinvested our earnings into a lab and an X-ray, and have it turnaround in 24 hours. So because of that we became more preferred as a provider."

How he discovered the market for health checkups for foreigners was a more fascinating one: Loh happened to come across a group of Indonesians at a lift lobby at Mount Elizabeth Hospital, and after awhile of listening to their conversations, he realised they were not there with any specific ailment, but instead for health checkups.

"So I asked myself, Why do they want to see specialists for health screening? It's like taking a hammer to kill a fly. So I was discussing with Choon Yong, like why don't we set up a specific service for health screening, and that's how we did it."

They learned that the management of the old Meridian Hotel had strong ties with the airline Garuda Indonesia, which would fly in Indonesian tourists to stay at the hotel, shop on the Orchard belt, and after Raffles Medical set up a small health screening service clinic at the hotel, also get their health screenings done then and there.

And Loh himself seems to have found a niche with the crème de la crème of international patient clientele — a couple of governments send their entire Cabinets to Raffles Medical for annual checkups, with no less than their Prime Minister having to see no less than Loh, and up till Covid-19 struck, Loh says he would see six to eight Indonesian clients for full-body health screenings.

Raffles Medical in the Covid-19 pandemic: more involved than you might expect

Now you might be wondering, given the ongoing pandemic, what kind of role Raffles Medical as a private healthcare group played in Singapore's overall efforts to curb the spread among our population.

Thanks to Loo's unwavering patriotism, the answer is: really quite a lot, actually.

Last year, at the height of the crisis with the explosion of cases among our foreign worker dormitories, the Group expanded its flexible workforce by 1,300 to:

- Provide care, swabbing and screening for Covid-19-positive patients who were moved to recovery and isolation facilities at the EXPO and Changi Exhibition Centre from April to December,

- Send teams of more than 50 doctors, nurses and healthcare staff to test residents of over 40 dormitories over five months,

- Run air border screenings in the early days in January 2020 for passengers arriving off flights from Wuhan, and other cities, and

- Run tests for travellers on the reciprocal green lanes.

Most recently, the Group also designed and got up and running Singapore's first vaccination centre at Changi Airport's Terminal 4 in five working days, and now operates 13 centres islandwide.

On these, Loo speaks with great pride, but also opened up about the grave concern he felt when Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean shared the figures involving the number of foreign worker infections last year with him in a meeting, while appealing for help from Raffles Medical.

"So we were asked specifically, 'Can you help?' when actually we got no troops. Our existing staff were all quite exhausted going to the dorms and all that. So my team medical director said, 'Dr Loo you go to the meeting, please don't promise.' I went there, I saw the problem. So I said I have to go be the chief apologist and say no. But when I saw this data, I thought wah, it's very serious. Actually I did not commit, you know, I kept quiet. There was a lot of pressure on us. They were hoping that we can help them."

Loo says he brokered a deal with SM Teo, offering to pull in his medical staff from Vietnam and China, provided the Singapore government expedited their clearance. Sure enough, they pulled through, and Raffles Medical was able to bring back "a few hundred" more nurses to support facility care efforts.

Secrets to preserving a friendship from 45 years of business partnership

Loo at the launch of Raffles Medical's IPO in 1997. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Loo at the launch of Raffles Medical's IPO in 1997. (Photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group)

Those years of rapid growth saw Loo and Loh come together at various points over the decades to make pivotal decisions that dictated the direction in which Raffles Medical would grow — some of these included deciding to expand overseas (Raffles Medical now has hospitals in China, and clinics in Cambodia, Vietnam, Japan and various parts of China), and listing on the Singapore Stock Exchange.

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

What, I wondered, is the secret the two of them have to staying friends after so many years of working together — after seeing so many others fall by the wayside, end very acrimoniously and often with costly legal battles?

The answers, according to Loh, are

a) to agree to disagree:

"We never had any friction but of course like everything else, we do have occasions where we disagree. But I think from the very start, when we started the partnership, the understanding between us was that we agree to disagree. And we take it from there."

And

b) to know and understand each other so well that they can trust each other with their complementary strengths:

"I must say my good friend Choon Yong, he's got a very sharp... he's got an attitude to look for business. He knows opportunities when he sees them. And of course that helps. But as I always insist, he does the business side of things, because I don't really fancy doing the business side; I concentrate on the professional side.

So I sit on, I chair the Quality Committee, and we look into our patient care, quality of care, how well we are doing in terms of patient care. And I sit on the ethics committee. And I sit on the accreditation committee where we accredit specialists who want to work here.

So this is what I'm comfortable with and what I like to do. So in a way, we complement one another. He knows he can leave this part of it to me, and I know I can leave the business side to him. So that's how it works out so well."

Truthfully, at the ages of 72 and 74, I marvel at how Loo and Loh still seem to be going strong in their active, daily involvement in Raffles Medical Group.

As huge as this "practice" has become, this still is very much their baby, but both of them, separately, did also speak to me at length about the legacy they are working so hard to leave behind, institute and cement in the hallowed halls of their shiny flagship hospital building.

Perhaps I shouldn't have been surprised, but I was pretty impressed by how Loh accurately pinpointed the one thing Loo acknowledges gnaws at him:

"When we exit the stage, will Raffles still maintain the character that it is? And in the earlier years, our motto was 'to our patients our best'. And whether that motto, and that approach to practice, really is something that will permeate through the many layers, you know, not just at doctor's level, but also the nurses' level, the dispensers' level, even the back room people's level, you know, all that, whether that philosophy, that approach to running the group, will be diluted."

And this is definitely something we hope the two wise doctors can put their heads together to figure out how to prevent from happening.

Watch the Beyond the Glass Door video interview with Loo on Facebook:

Lessons on Leadership is a new Mothership series about the inspiring stories of Singapore’s business leaders and entrepreneurs, as well as the lessons and values we can learn from their lived experiences.

Stay tuned for our next interview with Ya Kun Group chairman Adrin Loi and his son Jesher later this month.

Check out our first two interviews under this series here:

Top photo courtesy of Raffles Medical Group, bottom photo by Jeanette Tan

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.