Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Alvin Philemon Makundi was born in Singapore.

He grew up here, and — like other children in Singapore — worked his way through our education system.

He’s now serving National Service, and along with his peers, eagerly awaits his Operationally Ready Date (ORD).

By almost any measure or rubric you can think of, Makundi, 22, is just like a regular Singaporean kid.

What stands him apart from most, however, is his appearance.

The son of Tanzanian immigrants to Singapore, Makundi is very much aware of the novel combination of his African roots on one hand, and Southeast Asian upbringing on the other.

In a short video posted online in January 2020, he tapped on the perceived dissonance between his voice and looks for comedic effect, effortlessly code-switching between a Singlish accent and a stereotypically African one.

growing up as an african in singapore mostly means my accent is confused pic.twitter.com/GqNvrRLAEk

— alvin.phil (@alvinpwm) January 23, 2020

In the 28-second clip, a blue dashiki (a colourful garment mostly worn in West Africa) makes an appearance, along with mannerisms and colloquialisms that can only be described as shamelessly Singaporean.

To top it off, Makundi finishes the video with a barrage of Mandarin, enunciated with the casualness of a native speaker.

On Twitter, the video currently has over 660,000 views, 22,000 retweets and 36,000 likes.

It has also been viewed over 746,000 times on TikTok.

Moving from Africa to Singapore

Makundi and I met at Kafe Utu, a restaurant on Jiak Chuan Road in Outram Park, which served cuisine enjoyed around the African continent. We were filming a video in which we tasted and reviewed the food.

When it was time to try the restaurant's lamb samosas, Makundi remarked that they reminded him of the trips he had taken to Tanzania.

"You don't really taste this kind of flavour in meat normally, [not] in Singapore at least," he said to the camera.

Of Kafe Utu's Swahili fish curry, Makundi told me that it was a dish his mother would make for the family, though she also cooked lots of dishes that would be familiar to Singaporeans.

Swahili Fish Curry. Image by Lim Jun Tong

Swahili Fish Curry. Image by Lim Jun Tong

"My mum loves tom yum. She'll make tom yum, like the instant noodle kind, but she'll add in a lot more ingredients.

And the way Africans like spiciness, it's the kind where you take one sip and you get an asthma attack."

It wasn't uncommon for home-cooked family meals to involve other local staples like fried rice or bak kut teh.

Makundi’s father, Walter, first arrived in Singapore in 1994, after a friend told the civil engineer about the abundance of opportunities available, as a result of the many construction projects undertaken by the rapidly developing city-state.

“My dad was like ‘LMAO, okay sure if it’s legit then buy me a ticket, then I’ll come’.

And his friend actually went through with it and got him a ticket.”

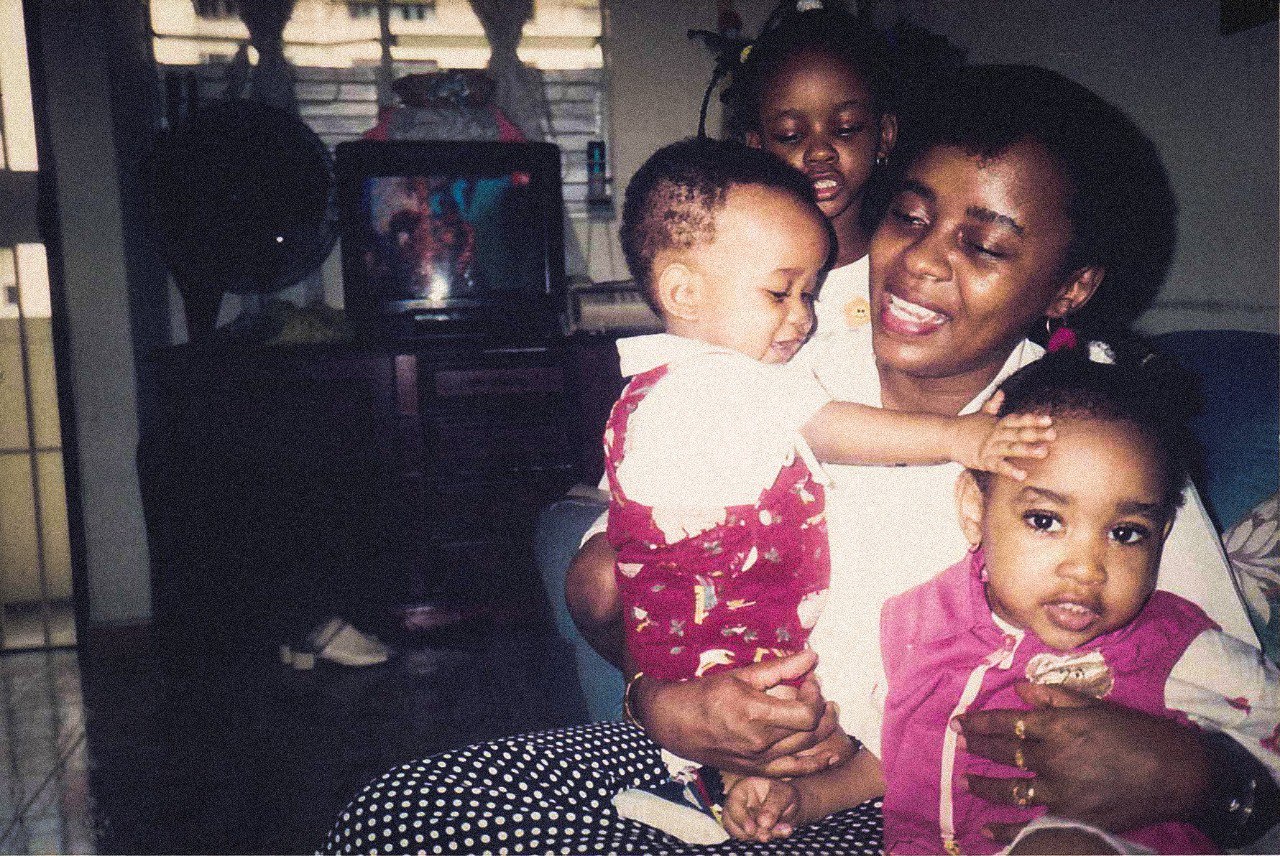

Two years later, he decided to bring over his wife, Angela, and their daughter Wendy, who was just two years old at the time.

“They were quite amazed by Singapore in general when they first came. I remember my mum mentioned something like she was at the airport and went to get a cab, and it was a Mercedes cab and she was shook.”

Makundi, the youngest of three siblings, was born in 1999 at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

The whole family are now permanent residents in Singapore, with Makundi and his sisters intending to become citizens.

The Makundi family (L-R) Wendy, Walter, Angela, Nancy, and Alvin. Image courtesy of Alvin Philemon Makundi

The Makundi family (L-R) Wendy, Walter, Angela, Nancy, and Alvin. Image courtesy of Alvin Philemon Makundi

The standard script of responses

As a young child, Makundi was unaware that Tanzanians, and more broadly Africans, were a rarity here.

He remembers as a primary school student, being peppered with questions about where he was from, an experience he described as “confusing”.

“You’re like ‘what am I?’ Because when you’re young you don’t really comprehend all that, you just know that you’re from Africa and that’s it.”

Makundi also vividly recalls Barack Obama’s meteoric rise to the United States’ presidency; the 2008 election occurring when he was nine.

He points to that event, along with the proliferation of social media, as really driving up curiosity about the African continent.

These days, it's not uncommon for Makundi to field a flurry of questions from strangers, be it private hire drivers or fellow shoppers in line at a convenience store.

“I have a standard script of responses to what people want to ask me. I’ve gotten used to the questions:

‘Where you from?’ — Tanzania.

‘How did you come here?’ — Parents, they found a job here.

‘How long you been here?’ — I was born here.

‘Oh, you study local school?’ — Yes.”

Yet, he also understands the curiosity that people have, and mostly views the quizzing as an opportunity to educate and dispel lazy stereotypes of uncivilised and pre-modern African natives living in squalor.

“Actually Africa is very different, its not like what you expect — like it being just this random rural place, random mud huts, there’s no internet, no electricity, everyone just sits around a fire.

We have cities, we have WiFi, of course. The data plans there are better than here; it’s messed up.”

Hurtful conversations

Inevitably, those whom he engages with fall into two groups, Makundi explained: individuals who are genuinely open to learning about Africa and Tanzania, and “people who believe what they already know is right and nothing can change it.”

Makundi ran me through a typical conversation with individuals in the latter category.

Such an individual, after being informed that Tanzania has multiple cities, skyscrapers, and other displays of development, might respond by dismissing Makundi’s claims: “Cannot be, I thought I saw it's just mud huts only,” or “That time I go there, it wasn’t like that”.

Perhaps more hurtful, is when Singaporeans use derogatory words — like the “N-word” — with Makundi.

“Older people tend to use it a lot,” he told me.

“The argument people have is always that ‘Oh those things happened in America not here.’

[But] I feel it’s a bit ridiculous for people [outside of America] to use words and kind of make fun of something that people in other countries are struggling with.”

Makundi refrains from using the word himself — even though some may say it’s acceptable for him to.

He explains that if he is to expect others not to use it, then he should set an example.

"It's part of my life"

I couldn’t help but feel admiration for the 22-year-old’s maturity when it came to his thoughts on race.

But I suppose he has had no choice but to confront the issue; while discussing and debating such topics can be an exercise in social media performance for some, for Makundi it is his lived experience.

He admits that getting questioned on his life by strangers can get to him — he describes himself as an introvert — “but you just have to deal with it… it's like part of my life I guess. Not only me but my whole family.”

“There’s also the other extreme of people who get offended for us, which is annoying,” he said.

Makundi recalled a recent incident where someone online had tried to cancel an Asian girl who was sporting cornrows and dreadlocks; she had been accused of “profiting off Black culture”.

Makundi personally didn’t feel that the Asian girl had done anything wrong, but was inadvertently dragged into the argument when people started tagging him in Tweets.

“They were just trying to reach harder and get people triggered.”

I asked him about his experience thus far in National Service — where machismo and rigid pecking order can sometimes create an environment where inappropriate jokes and comments thrive — and it becomes apparent that for Makundi, there is often an element of having to discern people’s intentions during interactions.

For example, his Indian section commander in Basic Military Training (BMT) took to calling him “Black Panther” and would regularly approach Makundi with his fists clenched and arms forming an “X” over his chest, mimicking the Marvel superhero.

“I mean he was a really cool guy. I could tell he was not trying to be offensive and all that. So it was fun, I guess.”

The difference between African parents

His experiences in National Service were also a springboard to Makundi’s budding career as a content creator.

Take for example, the BMT passing out parade, where graduating soldiers often commemorate the moment with pictures with their parents.

The Makundi family’s version of the Singaporean tradition involved two photos with each of his parents, who later shared them on their respective social media accounts

Makundi took screenshots of his parents’ posts and uploaded them onto his Twitter account, calling attention to the apparent disparity in their tone:

the difference between an african mom and dad pic.twitter.com/HdQk1PrqA0

— alvin.phil (@alvinpwm) December 6, 2019

The tweet drew a humorous comparison between Walter’s dad joke (“Sometimes I need armed bodyguard”) and Angela’s sincere pride (“what an honour to see you marching like a real soldier”).

“It blew up, because you know, people are surprised that there’s an African doing NS.

Someone actually went up to my dad at Cheers and asked him if he needed an armed bodyguard!”

From then, Makundi started posting memes, as well as more comical observations about his parents, before venturing into skits.

These skits — which are often a family affair involving all three siblings and sometimes their parents — play on the surprise of hearing Tanzanians speak Singlish, and the family’s interactions with Singaporean culture and norms.

“We are close and chill,” said Makundi, describing the relationship between him and his siblings.

Image courtesy of Alvin Philemon Makundi

Image courtesy of Alvin Philemon Makundi

“I think Nancy (24) and I — cause we are technically Gen Z — we get along easier and understand each other better,” he added, citing their shared “chaotic energy”.

“Wendy (27) is a Millennial so there’s a slight difference but the dynamics work.”

Nancy, Makundi told me, is also pursuing a career in content creation.

"What does it mean to 'look Singaporean'?"

Reflecting on how he felt about the kick Singaporeans seemed to get out of the incongruence between his appearance and how he spoke, Makundi described being perplexed.

"It honestly didn't feel like it was something that impressive cause living in Singapore made me just feel like I was a Singaporean," he said.

"I only have instances where I would be reminded that 'ah yes I look African, that’s why'."

The popularity of his content had entangled itself with one of the big questions he had asked himself throughout his upbringing — "What does it mean to 'look Singaporean'?"

"I never thought there was a look to it, and I guess for me, I feel like a Singaporean, grew up in Singapore, and behave like a Singaporean.

I guess my videos are a way of showing that a Singaporean can look like anybody. It's an opportunity to help change that perception."

Back at the restaurant, we were being served malindi halwa — a Swahili dessert made with fresh dragon fruit, hazelnuts, and cashew nuts.

Malindi Halwa. Image by Lim Jun Tong

Malindi Halwa. Image by Lim Jun Tong

After taking one bite into the deep red rectangular gelatinous treat, Makundi turned to the camera.

In line with the format of the video we were shooting, he was required to give a concise description of the dish.

"Basically, (it's an) African version of kueh."

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top image by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.