Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

At age two, Norshahira Bte Amat Paiman was hit in her right eye by a toy gun while playing with friends.

Norshahira, who is known as Shahira, has lived since then without sight in one eye, but her troubles didn't end there.

Years after the accident, she began to experience "terrible headaches".

As a secondary school student, she was diagnosed with glaucoma, a condition affecting the optic nerve.

The painful headaches had to be kept under control with the help of special eye drops, as well as laser surgeries to reduce the pressure on her eye.

But her condition continued to worsen over the years — in 2019, she developed a corneal abscess and a corneal ulcer.

"I was experiencing very bad pain — terrible, terrible pain," says Shahira, now 31, explaining that the pain disrupted daily life.

It wasn't just physical pain that made her condition unsustainable — the eyedrops Shahira had to use to manage her condition were pricey as well, and she was worried about the side-effects of her painkillers.

"If I can just remove this eye..." Shahira wondered aloud one day, during a doctor's appointment at the NUH Eye Surgery Centre.

Her doctor, upon hearing that she was open to having the non-functioning eye removed, kickstarted the process that would change her life by introducing her to Suriya Abu Waled, NUH's sole ocularist, and a team of surgeons.

"They were very nice," says Shahira. "They sat down, they talked to me, explained the process and everything."

It couldn't have come at a better time for her. Her defective eye was hindering her nursing work, she says.

"I was going through a mode where I was very depressed about it. Because I'm working as a nurse [and] I enjoyed doing nursing."

Initial doubts

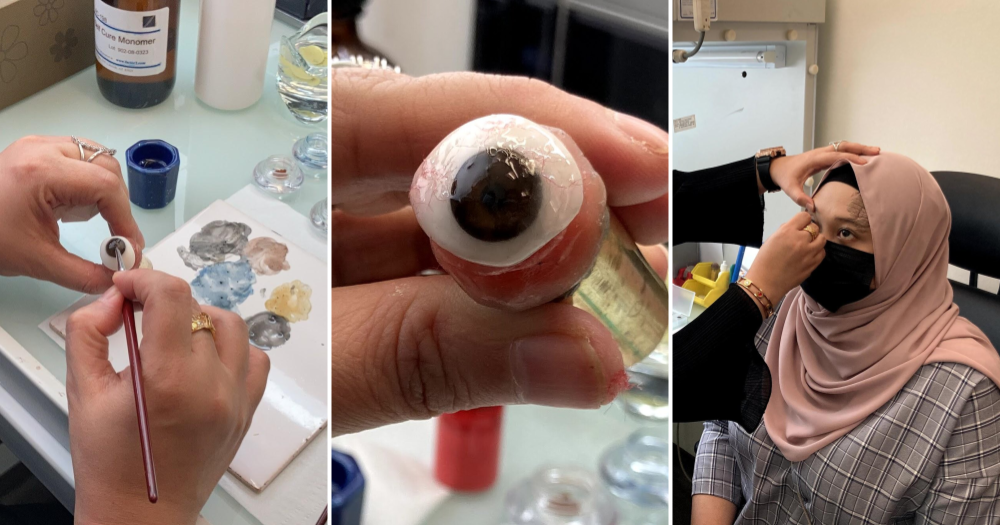

The plan of action set out by the medical team was clear — enucleation, or a removal of the eye that leaves the eye muscles and other surrounding structures intact, followed by the fitting of a prosthetic eye, or prosthesis.

Part of a prosthetic eye, after being painted, and before it is taken to be polished. Photo by Nigel Chua.

Part of a prosthetic eye, after being painted, and before it is taken to be polished. Photo by Nigel Chua.

But it was still a difficult decision for Shahira to make, and even up till the day before the surgery in September 2020, she was still wondering: "Did I make the right decision?"

Cases requiring enucleation are rare, and Suriya sees around 15 patients a year, on average.

Shahira shares that she had difficulty finding out more about the procedure and how it would help — or hinder — those who had their eyes removed, especially when it came to information or stories of the process from the patients' point of view.

Still, the scant accounts she found from patients overseas gave her some confidence to decide: "Okay. Let's go for the surgery."

Meanwhile, Suriya, an ocularist at NUH for the past 14 years, explained that her role in the process was to build rapport with her patient, to "give her confidence" to go ahead with the surgery and prosthesis.

What really sealed the deal for Shahira, however, was one of her patient's unexpected, but poignant remarks to her.

"None of my patients have ever really commented [about my eye], until [a patient] said this to me, like, you know, 'you yourself are not well, why don't you take care of yourself before you take care of me?'"

"That's why I decided," says Shahira. "This shouldn't be going on."

Life changed

Since going through the surgery in September last year, and getting the prosthesis fitted, Shahira's life has taken a turn for the better, as her initial doubts were slowly disproved.

Thankfully, Shahira's eye socket remained in good condition after the eye was removed, which means that her prosthetic eye moves as if it were a real eye.

"Unless I remove it... nobody knows," she says.

"You don't look different," some of her colleagues remarked, asking her if she had gone for an "eye transplant", despite knowing that such a procedure has never been done before.

"I already told them it's a plastic eye... but they said, 'it looks so real!'" Shahira recalls, laughing. She was even asked by one incredulous colleague, "Can you see?"

A doctor whom Shahira works with remarked that she looked nicer, before quickly adding "I mean, last time you look cute lah, but now you look cuter."

Shahira pauses and smiles, as she tells us that she is "much, much happier now."

Besides the boost in confidence because of her new appearance, having the procedure done means that she no longer suffers from the debilitating pain, which held her back from pursuits such as driving lessons, for fear that the pain would come while she was at the wheel.

Shahira's prosthetic eye — and how real it looks — has also had a positive impact on her work as a nurse.

Previously, skeptical patients would question her ability to carry out simple procedures because of her defective eye. These are tasks that she can perform without issue — such as drawing blood, or putting the patient on an IV drip.

Now, thanks to her prosthetic eye, her patients no longer doubt her abilities.

From patient to friend

It's patients like Shahira that make it all worthwhile for Suriya.

Photo by Nigel Chua.

Photo by Nigel Chua.

The two have clearly built up good rapport, with Shahira referring to Suriya as "Kak Su" (Sister Su) as she recalls how the ocularist guided her through the entire process.

They will meet again in March, when Shahira returns for a follow-up appointment.

Such appointments are important, Suriya says, to ensure that the prosthesis continues to be well-fitted. The prosthesis will also be polished.

Suriya explains that prosthetic eyes must be well-polished, as bumps or irregularities can irritate the wearer's eye socket and cause infections. GIF from video by Nigel Chua.

Suriya explains that prosthetic eyes must be well-polished, as bumps or irregularities can irritate the wearer's eye socket and cause infections. GIF from video by Nigel Chua.

But Suriya's hard work is sometimes unappreciated.

Difficult patients is something she jokingly says is the only reason why she gives her job a nine out of 10 rating, instead of 10 out of 10.

Patients have even asked her to redo their prosthesis.

"Each time when you do the process you have to explain to them," says Suriya. "You can't promise them 100 per cent," she says, because the outcome does vary from case to case.

For example, it is "quite difficult" to make a prosthesis for patients who have reconstructive surgery on their eye socket, as the shape of the eye socket may end up irregular.

What helps her in such situations is being able to put herself in their shoes. "I will not blame patients," she says, explaining that she can understand why they want the results to be as perfect as possible.

In such cases, Suriya has to take the time to patiently explain why the prosthesis may not be up to their expectations.

In other cases, however, Suriya might suggest that a prosthesis be re-done, or modified if it does not meet her own standards.

After all, "you will not know until the last [step], when you dispense the prosthesis [and] the patient wears it, then you can know whether the prosthesis really looks natural."

"Art and science"

Ocularistry, Suriya explains, is both an art and a science.

It takes around three days to create a prosthetic eye, from the first meeting with the patient to the point that the prosthesis is fitted.

Suriya has to follow the required steps exactly, and one mistake may mean that the entire prosthesis will have to be re-done.

The process starts with Suriya taking an impression of the eye socket using an alginate solution, to ensure that the prosthetic eye fits the patient exactly.

The prosthesis itself is made of acrylic, and customising it for a patient involves hand-painting each one to ensure that it matches the patient's natural eye colour.

Suriya mixing different colours of powdered pigments. GIF from video by Nigel Chua.

Suriya mixing different colours of powdered pigments. GIF from video by Nigel Chua.

We watch as Suriya deftly mixes powdered pigments in different colours, before applying them to the prosthetic eye with a small paintbrush.

Prosthetic eyes are hand-painted by Suriya. GIF from video by Nigel Chua.

Prosthetic eyes are hand-painted by Suriya. GIF from video by Nigel Chua.

Fine red thread is also used to mimic the appearance of veins in the eye.

After the eye is painted, and the thread applied, the eye is then coated with a transparent monomer layer. This allows it to be polished smooth when the coating hardens.

The patient can then try on the prosthesis, allowing Suriya to make any necessary modifications to ensure that the patient is comfortable with their new eye.

As a person's eye colour can vary depending on the lighting, it is almost impossible to achieve a perfect match to their natural eye colour. Photo by Nigel Chua.

As a person's eye colour can vary depending on the lighting, it is almost impossible to achieve a perfect match to their natural eye colour. Photo by Nigel Chua.

There were no exams involved in the two-month training stint that Suriya attended, at the start of her ocularist career.

Many of the skills that she picked up were learnt "on the job", she tells us, sharing that she did not have any background in art or painting when she first started.

Not for everyone

Evidently, not everyone can be an ocularist, which explains why Suriya is NUH's first and only one.

"I do have assistants before, but they come and go," says Suriya. "Actually it's not an easy kind of job."

Suriya, however, enjoys the challenge that comes with the role, as well as the fulfilment that can come from seeing patients who are happy with the prosthetic eyes that she makes for them.

An added benefit, she says, is that "the doctors understand your job, they know what you're doing, and they respect you," adding that she has "free rein" to do her work.

She doesn't plan to stop, as long as she is "healthy enough to still continue."

"I love my job so much," Suriya says. "It's part of me, it's my passion."

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.'

Top image by Nigel Chua

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.