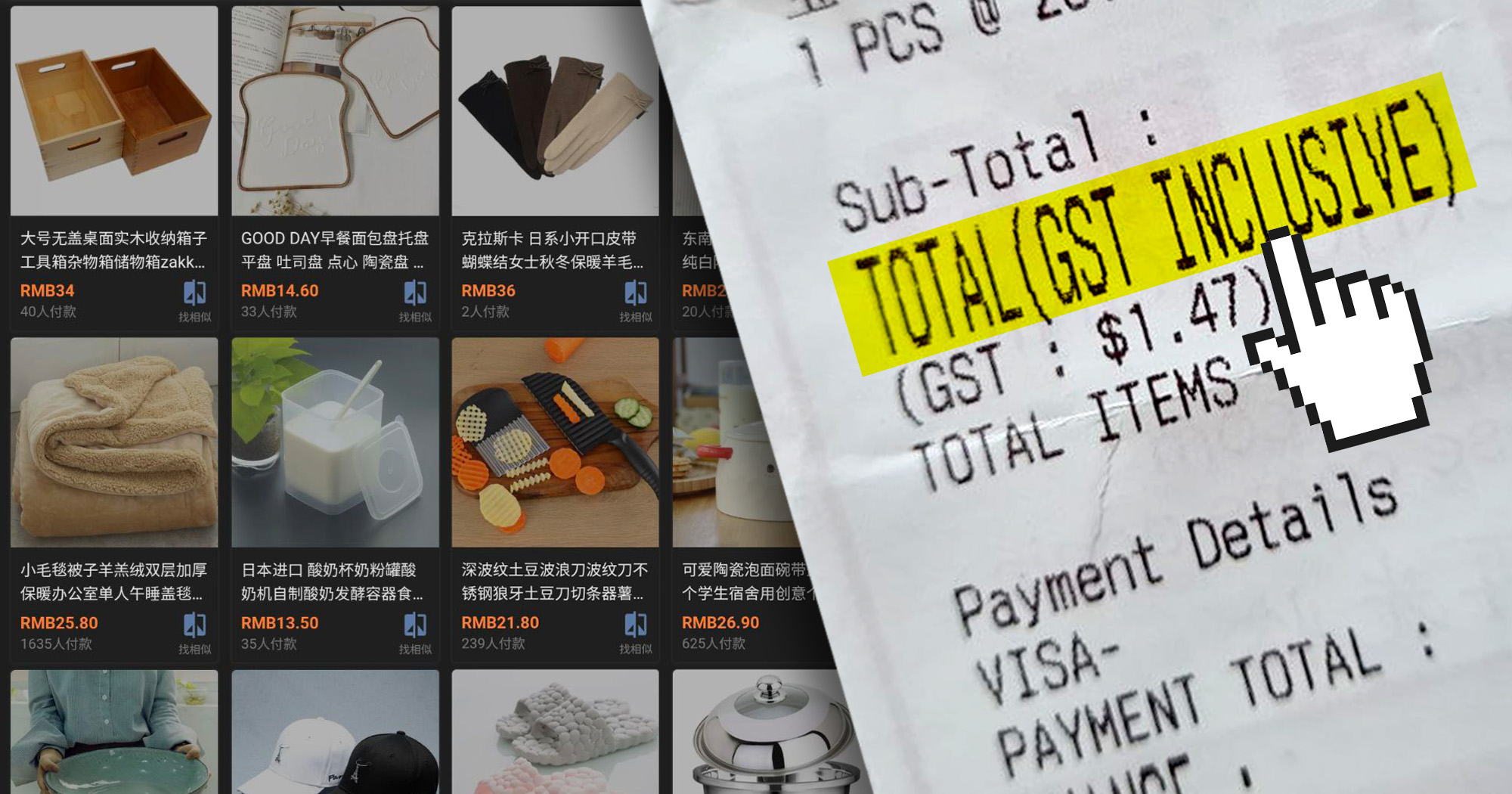

So, your Taobao phone cases and shoes from Amazon are going to be slapped with a Goods and Services Tax (GST) from 2023.

This announcement came just after the GST was extended to imported digital services (like Spotify and Netflix's streaming services) in January 2020.

Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat said in his 2021 Budget speech that these changes would ensure a "level playing field for our local businesses to compete effectively".

All good, but people in Singapore have been shopping online for a while now. So, why did it take so long to levy GST on these low-value imports?

There are certain difficulties that come with taxing suppliers outside Singapore, but first, before we head there, we need to get a handle on what the GST is and how it is collected.

What is GST and how does IRAS collect it?

There are different types of taxes — income tax, road tax, property tax, and of course, the GST, just to name a few.

The GST, in particular, is a tax that you pay for most goods and services that you either 1) bring into or 2) purchase in Singapore.

The most straightforward example of the GST is the 7 per cent tax that you incur when you purchase a product or service in Singapore — for instance the S$0.52 GST included in a S$7.90 McDonald's McSpicy Extra Value Meal.

When you pay for a McSpicy Extra Value Meal, McDonald's collects the S$0.52 GST, along with all the other GST from the rest of its customers on behalf of IRAS and hands it over to the tax authority.

This arrangement works because McDonald's is a business entity registered in Singapore, bound by Singapore's laws.

What if you buy from a business that is not registered in Singapore?

Let's say you want to ship a fancy sports car from Spain, or perhaps cross the Causeway to bring back a large amount of groceries from Johor — both the car and groceries are liable for GST.

But since IRAS cannot possibly demand that the car manufacturer in Spain or the supermarket chain in Johor collect GST on its behalf, the burden then falls on you to declare the value of the goods and submit to IRAS the appropriate amount of GST.

Tax leakage from low-value purchases

It gets trickier with low-value purchases — think shoes, dresses and phone cases — that you buy from overseas merchants.

It would be quite a logistical nightmare to declare the value of every single item that you purchase, yet at the same time, if small purchases aren't charged GST, then there exists a tax leakage.

Let's say you are looking for a book.

Kinokuniya at Takashimaya sells it for S$40, inclusive of GST. However, you are able to get the same book from Book Depository for S$35 without any delivery cost, and definitely without GST.

Both options allow you to get the same product, yet for the online purchase, there is tax revenue lost.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recently noted that GST exemptions for low-value imported goods have become "increasingly controversial" because as more consumers buy stuff online, these exemptions lead to lower tax revenue collected, and "potentially unfair competitive pressures" on domestic retailers.

Hard to ensure compliance among players

The new announcement that GST will be extended to low-value items purchased online can address this tax leakage.

One way this can be done is to get the e-commerce sites like Taobao and Amazon to charge GST on every transaction made by Singapore consumers on their platforms, on behalf of overseas sellers.

They will collect the tax and hand it over to IRAS.

However, there is no way the tax authority can ensure that these overseas-based platforms will comply with the new tax requirements because they don't fall under Singapore's jurisdiction.

That said, Tax Practice Leader Loh Eng Kiat from accounting firm Baker Tilly Singapore told Mothership that the "broad consensus is that larger businesses will do their utmost to satisfy their obligations so that they are not perceived negatively within a 'court of public opinion'".

"By simply fostering compliance from a smaller number of (larger) sellers, [the authorities] could conceivably collect a significant proportion of the tax revenue at stake (i.e. applying the 80/20 rule)," he said.

Singapore watches and follows

GST-related changes are also very complex and not easy to implement, said Loh.

"Apart from vendor needs (e.g. changing their systems to facilitate GST compliance), there may be political pressures not to do so. As an extreme example, Hong Kong could not even introduce a GST regime after years of trying, and appears not to be even trying anymore."

As such, many developed economies have had to delay their GST (or equivalent tax regime) changes.

Australia initially planned to implement a 10 per cent GST on clothing, electronics and furniture purchased from overseas retailers with a value of under AU$1,000 (S$1,045) in July 2017. It was later delayed to July 2018.

The European Union had to delay the effective start date of its complex new VAT (Value Added Tax) model more than once.

For this reason, it could be that Singapore chose to adopt a pragmatic approach and adopt a "fast follower" (as opposed to “first mover”) approach, said Loh.

Mothership Explains is a series where we dig deep into the important, interesting, and confusing going-ons in our world and try to, well, explain them.

This series aims to provide in-depth, easy-to-understand explanations to keep our readers up to date on not just what is going on in the world, but also the "why's".

Top photo by Joshua Lee.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.