It was a Friday morning in late-October when my colleague, Andrew, and I wandered into a bustling second-floor food court in Serangoon.

There was a row of food stalls selling chicken rice, rojak, western food, noodles, and more, as well as a spread of tables with small groups of people scattered about, sipping their morning kopi and chatting.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Looking around, there's really nothing much to distinguish it from any other kopitiam in Singapore.

However, these food stalls are different than most others for one major reason — they are operated by differently-abled individuals.

Founded to support differently-abled individuals

We were there that morning to speak with 61-year-old Koh Seng Choon.

Koh founded Project Dignity in 2010 as a social enterprise, with the goal of creating jobs for people with disabilities.

These include people with physical disabilities, mental illnesses, intellectual disabilities, and individuals who face social challenges, such as single motherhood and being primary caregivers.

Out of Project Dignity's around 70 staff members, more than 60 per cent are from these marginalised communities.

In his younger days, Koh had worked overseas as a business consultant for many years.

After coming back to Singapore in 1997, he made sure to volunteer his time to give back to the community at least once a month, calling it "Dignity Day".

But as time passed, he realised that he wanted to do more than just ad-hoc volunteering.

"The idea my mum always taught me is [from age] zero to 25, you learn. 25 to 50, you earn. But 50 onwards, return.

Because birth and death is definite. The Chinese say, '生不帶來,死不帶去'. Born with nothing, go with nothing."

"I'm doing what I set out to do, that's my philosophy," Koh said, seated across from us at one of the tables.

61-year-old Koh Seng Choon. Photo by Andrew Koay.

61-year-old Koh Seng Choon. Photo by Andrew Koay.

Koh explained that Project Dignity has four key principles: providing skills, helping to obtain gainful employment, integration, and inclusion.

"Our job here is very simple," Koh explained matter-of-factly. "To educate, to engage, and to inspire."

Starting as four small stalls at Balestier, Project Dignity has grown and moved over the years, to Kaki Bukit in 2011, then to Serangoon, and most recently, opening in their biggest space yet at Boon Keng earlier this month.

Train-and-Place programme

In the middle of his enthusiastic explanation of the ins and outs of Project Dignity, Koh suddenly turned and asked us, as we sipped on our drinks, "Can you cook or not?"

When we feebly responded that we're not very good cooks, Koh replied emphatically,

"Cooking is a skill! And it's a need, not a want. Y'know, you need to eat!"

The first two principles of Project Dignity — providing skills and helping to obtain gainful employment — are achieved through the Train-and-Place programme at Dignity Kitchen, the kopitiam run by Project Dignity in which we are sitting and chatting.

"A lot of social enterprises go and [teach] knitting, handicrafts. How many handicrafts do you buy?

You need to eat! It's like breathing. So we must skill them first."

The Train-and-Place programme gives trainees a chance to develop skills in food preparation, cooking, and serving of hawker fare through a 22-day training programme.

A trainee cutting steamed chicken for chicken rice. Photo by Andrew Koay.

A trainee cutting steamed chicken for chicken rice. Photo by Andrew Koay.

Photo by Andrew Koay.

Photo by Andrew Koay.

"Eh, our training got money one," Koh said playfully.

He took on a more serious tone, though, as he added, "In Singapore, there's no minimum wage. Disabled people are not properly paid."

The intensity in his voice rose as he recounted how one employer exploited their differently-abled staff by withholding their salary for a full year because they were under "training".

So at Project Dignity, trainees are compensated for their work during training — which happens over six to eight weeks — about S$4.50 per hour.

Focus on ability rather than disability

"Don't look at their disability. Look at their ability," Koh explained about Dignity Kitchen's approach toward training the individuals it works with.

"Because they have different disabilities, they have different issues. There's no one solution for all."

Instead of focusing on what they can't do, Dignity Kitchen instead tries to customise the training to what each trainee can do.

One man who is paralysed on half of his body due to a stroke, for example, has developed his skills to be able to peel and cut vegetables with only one hand.

Dignity Kitchen also has a number of innovative machines that aid its differently-abled employees in preparing food.

For example, the claypot rice stall utilises a traditional claypot machine that cooks the rice with just the push of a button, so that the staff only need to add the ingredients to the pot.

Andrew ordered a bowl of Sarawak kolo mee, while I opted for my favourite hawker meal — a plate of steamed chicken rice.

Andrew's Sarawak kolo mee. "Unique and tasty," he remarked. Photo by Andrew Koay.

Andrew's Sarawak kolo mee. "Unique and tasty," he remarked. Photo by Andrew Koay.

My steamed chicken rice. I'm getting hungry just looking at it again. Photo by Andrew Koay.

My steamed chicken rice. I'm getting hungry just looking at it again. Photo by Andrew Koay.

Both of our meals were prepared by differently-abled trainees and both were delicious.

Importance of personalised care

After successfully completing the training, the individuals are then placed in one of Dignity Kitchen's F&B partners.

The programme, which has placed more than 1,300 individuals to date, has not been without its own share of hardships, though.

"Many years ago, when I first started this, I was very idealistic," Koh admitted, as he started to tell a story about one of his early trainees, who made him realise what was at stake in their work.

Photo by Andrew Koay.

Photo by Andrew Koay.

The trainee was a young woman with bipolar disorder who was trained by Koh, and was "very clever", he told us.

Koh was able to place the woman into a job which was very good for her, as her boss was very kind, he explained:

"Her first supervisor was very nice. [If] she was late, never mind. Buy her coffee, buy her lunch. Very good, she was so happy."

However, things changed when the woman had a change of supervisor. Based on CCTV footage that Koh saw, the new supervisor would "scream at her, shout at her, take things [and] throw at her".

One day, after work, the young woman went home and committed suicide.

Koh found out about the woman's death through a call from the police, as his name card had been in her pocket.

After that incident, Koh realised the importance of ensuring that Dignity Kitchen's trainees are placed in suitable environments.

Now, before a new business is able to hire an employee from Project Dignity, staff members go down to the workplace to evaluate the environment and the proposed job scope.

The Project Dignity staff also follow up with their former trainees for one year after they have been placed into their new jobs.

Integrating different communities

While the Train-and-Place programme addresses the skill and gainful employment pillars of Dignity Kitchen's principles, the broader space and programmes of Project Dignity aim to achieve the other two: integration and inclusion.

"Look around you," Koh said, gesturing to the bustling coffeeshop we were sitting in.

"This is an integration centre! You've got general public, you've got disabled people, you've got everything! All in one platform. Hawker centre is the best integration."

Part of Project Dignity's integration efforts include inviting elderly folks, who may not have the opportunity to go out much, for meals.

Every day, Project Dignity arranges for groups of the elderly to be picked up on a chartered bus and brought in for a free meal at Dignity Kitchen.

A joint event for the elderly by Bartley Neighbourhood Committee and Dignity Kitchen in 2018. Photo via Facebook / Seah Kian Peng.

A joint event for the elderly by Bartley Neighbourhood Committee and Dignity Kitchen in 2018. Photo via Facebook / Seah Kian Peng.

In the more than 10 years since its founding, Project Dignity has served free meals to more than 130,000 elderly folks in Singapore.

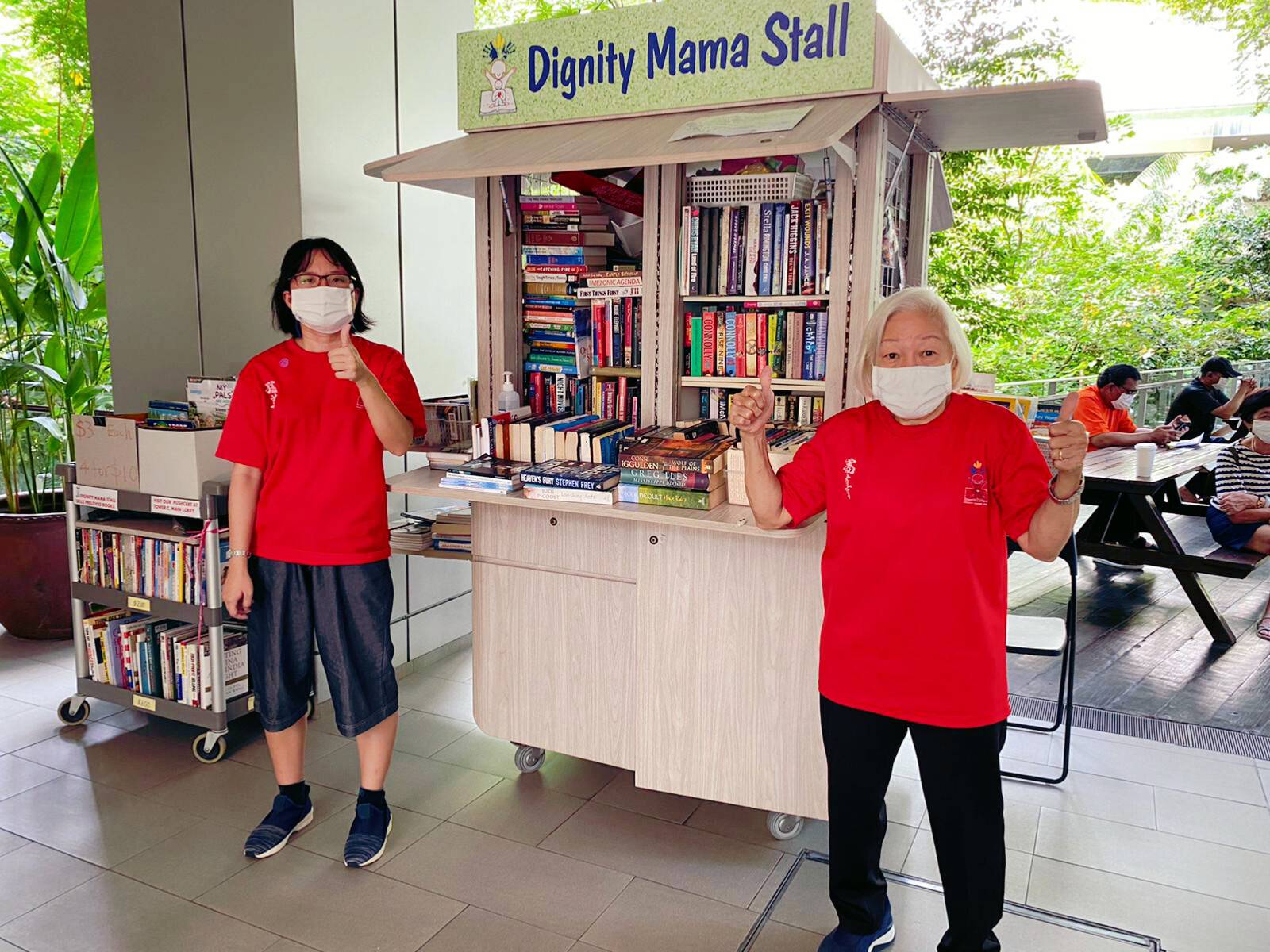

Another initiative under Project Dignity is Dignity Mama, which was created in 2012. Dignity Mama is composed of four stalls selling secondhand books, located in hospitals across Singapore.

The stalls are run by mothers and caregivers of children with special needs, together with the children themselves, in order to provide a source of income.

Jie Ying and her mother Eng Tee run the Khoo Teck Puat Hospital outlet. Photo via Facebook / Dignity Mama.

Jie Ying and her mother Eng Tee run the Khoo Teck Puat Hospital outlet. Photo via Facebook / Dignity Mama.

Koh with some staff at the NUH Dignity Mama outlet. Photo via Facebook / Dignity Kitchen.

Koh with some staff at the NUH Dignity Mama outlet. Photo via Facebook / Dignity Kitchen.

Including and educating the public

"The biggest problem in Singapore is empathy," Koh said, posing a hypothetical question to us to illustrate the stigma that exists in Singapore about differently-abled people:

"Let me put it this way — if I put a patch here [that reads] 'mental [illness]', big one, you will not buy, would you?"

Project Dignity's final pillar — inclusion — takes the form of bringing in the public to interact with the differently-abled staff. His hope is that the public will learn how to interact with people with different needs.

For example, my Milo peng order also involved a sign language lesson from Uncle Peter and Auntie Lisa, coworkers who have been working side-by-side at Dignity Kitchen for more than 10 years.

Auntie Lisa (left) and Uncle Peter (right) working hard to teach me some basic sign language. Photo by Andrew Koay.

Auntie Lisa (left) and Uncle Peter (right) working hard to teach me some basic sign language. Photo by Andrew Koay.

64-year-old Uncle Peter has been partially deaf in his left ear after a high fever in his childhood.

Auntie Lisa suffers from problems with her leg, and is also a caregiver for her ailing mother and two disabled family members.

Next to the drink stall, a small screen played an instructional video, showing me how to order my drink with sign language.

Alternatively, there was also a small box of cards representing different drinks, for customers to show to Uncle Peter what they wanted to order.

Cards to help with ordering. Photo by Andrew Koay.

Cards to help with ordering. Photo by Andrew Koay.

Project Dignity also runs team bonding sessions for members of the public and corporate groups to work with and learn from its differently-abled staff.

The path forward

With more than 10 years of running Project Dignity under his belt, Koh doesn't show any signs of slowing down.

"One of the things I've felt is that there are people out there that need help, and the queue is always very long.

So, I haven't stopped because I still think I can do a lot more."

In 2019, Koh expanded Project Dignity to go international, opening a 6,900 square foot Dignity Kitchen branch right in the middle of Hong Kong's Mong Kok district.

Since opening there, the Hong Kong branch has grown to have about 60 staff members, of which 49 are differently-abled.

Back in Singapore, Project Dignity recently made the exciting relocation from the second floor coffeeshop at Serangoon, where Andrew and I met Koh and his staff, to a new 10,000 square foot space at 69 Boon Keng Road.

The spacious 10,000 square foot location. Photo by Andrew Koay.

The spacious 10,000 square foot location. Photo by Andrew Koay.

The first day of Dignity Kitchen's operation was on Jan. 14, 2021, and from the looks of things, business has been booming.

They also plan to introduce a new pay-it-forward programme later in January, so they can welcome financially-needy residents to eat for free at Dignity Kitchen through the sponsorship of other customers.Throughout all the ups and downs that Project Dignity has faced over the years, Koh hasn't lost sight of what matters most to him: the individuals he is impacting.

"Actually, we are helping people. But we are not trying to change the world. We're not training hundreds and hundreds.

We're hoping to train one or two, and if they can do it, they can go on and live their life."

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top photo by Andrew Koay. Some quotes have been edited for clarity.

Totally unrelated but follow and listen to our podcast here

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.