Though it was almost 15 years ago, Alvin Ng still has vivid memories of his first encounter with a guide dog.

"You know for the sighted, (they have a phrase) ‘Love at first sight’? For me it was love at first touch," he said to me.

By this point, Ng — then 40 — had been blind for around eight years, and adapting to the circumstances had not been easy.

A chance meeting saw Ng chatting with one of the first guide dog handlers in Singapore outside the library at the Singapore Association Of The Visually Handicapped.

He remembered clearly how calm the dog was, laying obediently at its handler’s feet.

It was a far cry from the dogs he’d encountered in the past — a particularly traumatic experience of being chased by one as a young boy had since scarred Ng and made him afraid of canines.

Yet, curiosity piqued by the contrastingly docile animal, Ng began to brush his fingers along its short-haired coat.

"I had this expansion feeling," he said.

"This consciousness expansion feeling. It’s like ‘wow’. So after that, I couldn’t get it out of my mind.

So the next day, I got the guy’s number and called him: ‘Can you get me a guide dog?’"

"The last scene I can remember"

Ng lost his sight at the age of 31 in abrupt and unexpected circumstances.

He’d been sitting for his Masters in Business Administration (MBA) after completing a term of service as a regular with the military.

"I considered myself quite fit," said Ng, describing how in his younger days he’d consistently clock in sub-nine minute timings for his 2.4km runs.

Seemingly enjoying his physical prime, Ng didn’t have much cause for concern when all of a sudden he was struck with a month-long fever.

"I was hospitalised but nothing could be found," he said, explaining that with the fever came painful sensations in his joints.

His brother-in-law, a physician, treated Ng and eventually they managed to control the symptoms of the mysterious illness.

"That time I was still young so I thought nothing of it. I thought it would be cured. I still went to work… I was young, I never thought that something bad was going to happen."

But soon Ng’s condition would take a turn for the worst. Two weeks after he’d handed in his thesis for his MBA, Ng collapsed.

"Sunday morning, 14 December, suddenly my eyes became blur," Ng remembered.

He informed his brother-in-law, who he was staying with at the time, and they decided that Ng should go to the hospital for a check.

"The last scene I can remember — the last scene I saw — was that they drew the curtain for me to change. That was the last thing I could remember, I was putting my watch, my handphone, my wallet into the drawer," said Ng.

"That's about all."

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

10 in a million

It turned out that Ng was suffering from a rare auto-immune disease, though it was a complication during his coma that led to his loss of eyesight.

"Unfortunately, the (auto-immune disease) was so severe that I lapsed into coma and seven days (in) I actually was attacked by this complication called TTP. The full name is thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura."

The blood disorder — found in about 10 in a million individuals — causes blood clots to form in small blood vessels throughout the body. These clots block the delivery of oxygen to the body’s organs.

When Ng first regained consciousness 26 days after his collapse, he was still able to see colors and shapes — "I was quite ok."

But because the blood vessels supplying oxygenated blood to his eyes were blocked, Ng’s body compensated by growing new vessels around the blockages.

However, the new vessels were abnormal and weak, causing them to burst and fill Ng’s eyes with blood.

With the blood not draining fast enough, Ng’s eye specialist feared that the increased fluid would damage his retina and render him totally blind.

Deciding that damage control was the best course of action, she used a laser to burn off the blood vessels in his retina and salvage what she could of Ng’s eyesight.

"Walking is like horrifying"

Today, Ng has the ability to perceive light, but nothing else.

During our interview, I was seated about 1.5m in front of him, but Ng was none the wiser.

“I only can hear your voice. I also don’t know how far you are from me.”

As you might imagine, getting used to life without sight was not easy.

“For me everything I had to learn to do the blind way — my way. I didn’t have a very good rehab program… all was like my own trial and error.”

Simple tasks such as making a cup of instant coffee became a daunting exercise of grit for Ng, one that involved much fumbling and frequent scaldings.

“How do you know if the cup is full or not? You put your finger in!” said Ng, laughing.

“Walking is like horrifying. You walk into furniture, you walk into walls. What I hated the most was doors (that were) not open completely or closed completely.

When you walk there and bang into the corner of the door — you can try it — it's very very painful.”

Despite his relative sense of humour about the situation now, Ng told me that those first few years were indeed very hard and downright depressing.

After losing sight he mostly stayed at home; Ng’s wife told him: “If you go out, I don’t have the peace of mind to work.”

Though he’d been gifted a software that could read the content on his computer’s screen aloud, Ng avoided using it. The memory of the freedom he once had and the reminder of what he had lost was too much for him to deal with.

During his coma, several medical experts had told his brother-in-law that Ng was unlikely to wake up, and if he did he would be in a vegetative state.

“How I wished I’d be like that,” he told me of his feelings at that stage.

“So I don’t have to go through all this — all these years of nonsense.”

Ng told me that in those early days, he meditated a lot and did yoga as a means of coping.

Meeting Seretta for the first time

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

Having first encountered and learned about guide dogs in 2006 (which were virtually unheard of in Singapore at the time), it was six years before Ng finally got the opportunity to get one for himself.

In November 2012, Ng boarded a plane to Melbourne, Australia, and met Seretta, an 18-month old Labrador-Golden Retriever cross.

“It was kind of like, no expectation but at the same time looking forward to it,” said Ng, as if he was describing a first date.

He sat in a room waiting for a guide-dog handling instructor to bring Seretta in. When she finally arrived, the first thing she did was to scratch Ng’s hand.

“Then the instructor left the room, to let me spend time with Seretta. I was like: ‘Is this real?’”

“As they say, the rest is history,” said a chuckling Ng.

“The first time I walked with her was so surreal.”

The pair had 17 days of training together in Melbourne, where Ng learned how to handle Seretta properly under the guidance of an instructor. It was, as he described, a “honeymoon”.

After the training was over, Ng returned to Singapore, with Seretta in tow.

"The problem starts when you’re on your own with the dog."

“The dog now looks behind (and sees): ‘No more, the instructor is gone!” Ng told me laughing.

"Even simple instructions, she was not listening. It was quite frustrating."

Still a puppy then, Ng said that Seretta’s bubbly personality took some getting used to.

As a self-confessed “goal-oriented” individual, Ng worked hard at his handling skills, at the same time training Seretta to obey his instructions.

Yet despite the teething period walking with her was "freedom" for Ng.

"You finally can get rid of the cane. You walk like a 'normal' person, with increased speed... you also have the option to quicken your speed. It's like 'wow'. I've never looked back."

Building mental maps and trust

The work that Ng put in has evidently paid off.

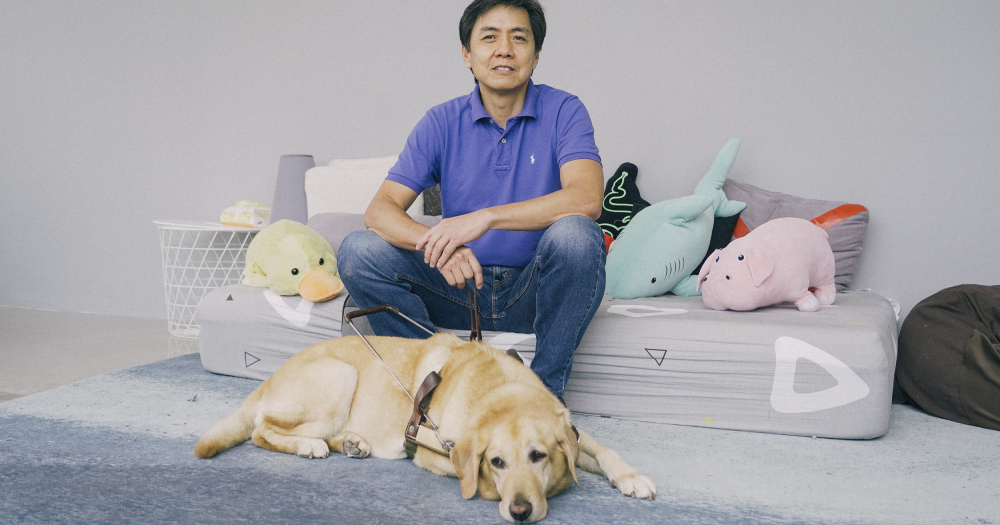

At our interview, Seretta sat silently at Ng’s feet, peacefully drifting in and out of sleep throughout the time I spent with them.

The only noise she emitted came from the occasional snores she made.

She’s still bubbly, explained Ng, but as soon as Seretta dons her guide-dog harness she knows its time to work.

Their working relationship is as such: When Ng wants to go somewhere, he first has to do his homework — figuring out the directions and paths to his destination and what mode of transportation he’ll take to the location.

“I build a mental map of it,” he said.

Once on foot, Ng directs Seretta and she leads him:

“When I need to turn down a lane — left or right — I’ll say first: ‘find left’. Then coming closer to the turn, I’ll say ‘left’ and she’ll turn.”

How does he know when exactly to turn? Ng said it was difficult to describe; it is done by a mix of intuition, experience, feeling of the texture on the floor, and paying great attention to his able senses.

“With a guide dog it’s very easy,” he explained.

“I’ll say: ‘find right’ and it’s her duty to find. Then (when I say) ‘left’ when we’re coming to a left, (she’ll know to turn) left. So I’ll follow her.

When crossing the road without any traffic lights, she’ll bring me to the curb. She’ll stop there and she’ll ask me what do I want to do. For me I’ll listen to the traffic… if it’s all clear, I’ll say ‘forward’. She’ll step down from the curb and we’ll cross to the other side.”

If ever Ng’s ears have failed him, Seretta is trained in what’s called “intelligent disobedience” — she’ll refuse to go through with his command.

For places that Ng and Seretta regularly visit — like the bus stop nearest to his house or Parkway Parade — Ng barely has to give her directions.

“I trust Seretta,” he said lovingly.

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

"This will greatly impact my social life"

While she may have given him newfound freedoms and restored a sense of possibility, not everyone has taken to Seretta the way Ng has.

Over the years, Ng has experienced resistance from security guards, restaurant staff, retail assistants, and the like for bringing a dog into their premises.

This is despite Singapore’s laws supporting the use of guide dogs in public spaces.

The Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) has also endorsed the use of guide dogs for those who need them, also adding that Muslims who come into contact with them need not necessarily cleanse themselves (though they may feel free to do so if they wish).

One particular rude incident last year saw a shop manager at a shoe store confront Ng with quite an aggressive tone.

“Out of nowhere from the back he came — I could hear how he spoke — ‘You have to mop my floor ah, later on.’”

The saving grace of that incident was the district manager, who happened to stop by the store that day. He apologised to Ng for how he’d been treated.

Ng walks away most of the time when faced with such opposition. One gets the sense that he might be tired from previous experiences of having to plead his and Seretta’s case.

"It’s quite frustrating when you actually have an appointment with your friends or family members at a place, and you go there and they tell you ‘No’.

This will greatly impact my social life, and it’s not nice."

For Ng, refusal to allow him and Seretta entry is a form of discrimination against blind individuals who are just trying to live their lives as sighted people do.

“You see, you look at my dog, it's very well maintained. It’s not like she's a very dirty dog, or she’s smelly. It’s not like when we go to a place she’ll bark away.”

More recently, he’s found pushback from private hire drivers, who Ng said, often cancel trips when they’re informed he has a guide dog with him.

While some companies do offer a pet-transportation option, Ng says that Seretta is not a pet, but something he needs to go about his daily life. Besides, he explained, drivers under that option run fewer in number than the normal private hire services.

Ng was also quick to add that he’s also had pleasant experiences with drivers keen to go the extra mile to help him out.

Ng's promise to Seretta

Seretta is now nine and a half, drawing closer to the age of 10 — which is the near-universally observed age of retirement for guide dogs, according to Ng.

Once that happens, Ng will have to find a new guide dog.

With the world currently in the midst of a pandemic, Ng admitted that doing so will be much harder. He is understandably anxious about the process.

What will happen to Seretta, though, once she hangs up her harness?

Many retired guide dogs are put up for adoption and find new homes with loving families. Most have three or four more years to enjoy before heading into a long and never-ending sleep.

"I will keep her," said Ng, firmly, when I posed the question to him.

"That’s my promise to her — I’ll keep her (as a pet).

After serving me for so many good years, I can’t bear to say: ‘you’re done, go’. No, I can’t do that."

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top image by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.