The 60-year leases of 191 terrace houses at Geylang Lorong 3 will run out on Dec. 31, 2020.

Those living in the houses will be required to return their units to the state, the Singapore Land Authority announced in 2017.

This triggered a flurry of articles in The Straits Times (ST) over the years, serving as repeated reminders to owners and the public that these leases, which started in 1960, were finally coming to an end.

It isn't just the owners of these leasehold properties who are affected, however.

As this marks the first time in Singapore that residential properties will be returned to the state, the handling of these leases' expiry will shed some light on what may happen when 99-year HDB leases come to an end in due time.

"No compensation, no extensions"

ST's initial article about the SLA announcement in 2017 characterised the forthcoming transfer of ownership as one where "no compensation" would be given, with "no extensions" granted.

Commenters were quick to make the connection to the 99-year HDB leases.

Screenshot via ST on Facebook.

Screenshot via ST on Facebook.

Screenshot via ST on Facebook.

Screenshot via ST on Facebook.

On the other hand, the pre-emptive warning issued by SLA could be considered charitable, as it was accompanied by the assignment of a dedicated SLA officer to each owner.

According to SLA, these officers went house to house to introduce themselves, and scheduled "a personal session with each household" with SLA, providing them with advice on their new housing options.

Furthermore, there is the fact that first-hand owners at Geylang Lorong 3 paid a relatively affordable sum for their homes — just S$4,850 for each unit, according to ST.

According to an inflation calculator by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), that works out to around S$18,000 in 2019.

Which is, in today's currency, paying S$25 per month to live in a landed terrace house.

It's quite a steal, but it should be seen in context of how these houses were built to accommodate those whose homes burnt down in a fire at Kampung Kuchai in the 1950s, ST reported.

Whether you see the end of the lease as compassionate/charitable or otherwise, one thing is certain: the state will take back residential land when its lease comes to an end, whether it is private or public land.

Extensions of leases have only been allowed in the case of en bloc redevelopments, with the requirement that developers top up an amount for the lease extension.

What will happen to the land?

SLA explained that the return of leasehold land to the state "allows the land to be rejuvenated to meet the new social and economic needs of Singaporeans."

A similar explanation can be found for the requirement that HDB flats be surrendered at the end of 99 years: their similarity to leasehold properties.

"In land-scarce Singapore, the leasehold system allows land to be recycled and re-developed, to meet the needs of future generations of Singaporeans," says a 2020 Gov.sg article, with a self-aware quip that it was a "re-lease" of the facts.

In that vein, the current homeowners at Geylang Lorong 3 will have to give way for new public housing, with SLA touting the new development as one that would meet the needs of Singaporeans, "especially those who wish to live near the city centre."

For HDB flats, however, the government is not waiting till the first 99-year leases expire to kick-start this process of rejuvenation.

SERS and VERS

Under the Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS), launched in 1995, flat owners from selected older HDB estates are relocated to new flats with new 99-year leases.

Their compensation may even include cash, if their previous home is assessed to be worth more than the replacement.

However, not all old estates will be selected for SERS. The Ministry of National Development (MND) said on occasion that it will be "highly selective".

Thus, the derivative Voluntary Early Redevelopment Scheme (VERS) was introduced in 2018 for those who, together with their neighbours, opt to surrender their flats to the government early in exchange for less-generous compensation.

Will any HDB leases come to an end?

The specifics of VERS have yet to be announced, given that it will not start for another few decades or so.

But what happens if the owners in aging estates reject VERS by voting against it? Presumably, they will be left on their own, to wait for their leases to run down.

This is not difficult to imagine, given the fact that compensation under VERS will be less generous than that under SERS.

Also, by the time VERS comes into the picture, the flats in question would — hopefully — still be in a highly liveable condition, as they would have gone through at least two rounds of upgrading (heavily-subsidised by the government).

Why are people still so unhappy?

These schemes seem to cover all the bases, so why are some still so unhappy?

To find the answer, one may have to go back as far as the 1990s.

1990s: "Asset enhancement"

Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong embarked on what was called an "Asset Enhancement Programme" after he became Prime Minister in 1990. Goh said, in 1995:

"In the 1960s and 1970s, we struggled to provide a roof for all Singaporeans. In the 1980s, Singaporeans were able to own their homes. Now, in the 1990s, we embark on a new phase where the Government increases your asset value through the Assets Enhancement Programme."

Enhancement of Singaporeans' assets would take place via upgrading programmes which would increase the value of HDB flats.

Under the MUP, homeowners enjoyed new amenities like drop-off porches, covered walkways, as well as neighbourhood parks and recreational facilities that took the place of open carparks which were converted to multistorey ones.

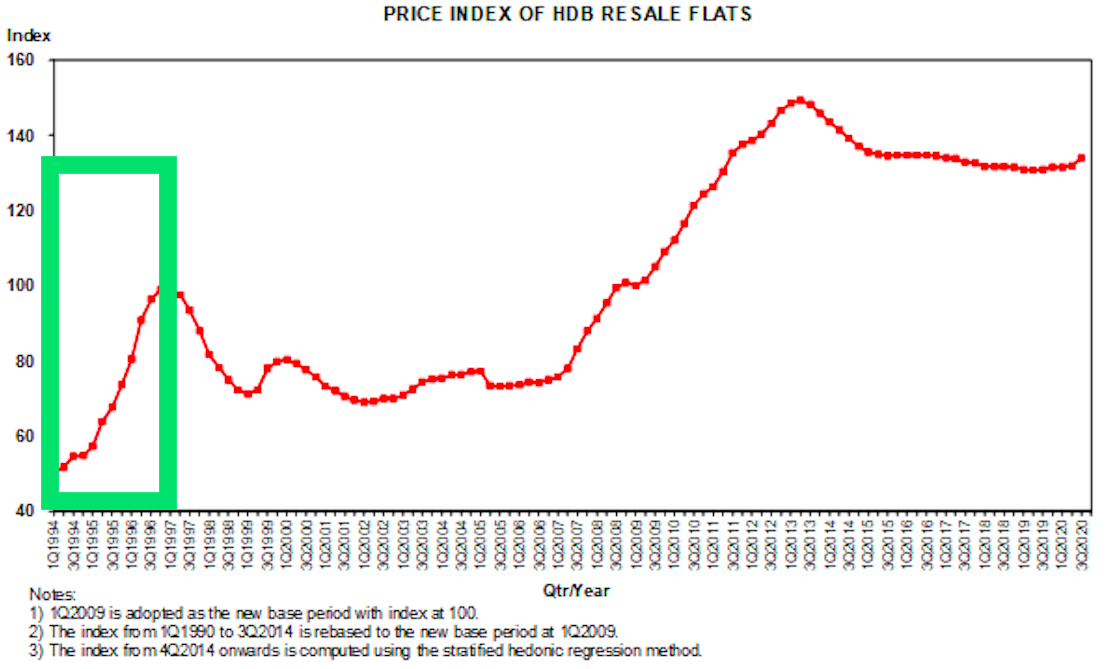

As Goh himself highlighted, the value of three-room flats in the Kim Keat area "doubled in the last three years", after the first of such upgrading programmes.

Image via HDB website.

Image via HDB website.

The success of asset enhancement policies was literally exponential — just look at the rapid rise in the resale price index in the 1990s, before the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997:

2000s: Asset enhancement continues

Talk of asset enhancement continued into the 2000s as well.

“We’re proud of the asset enhancement policy," then-national development minister Mah Bow Tan told the press in 2011.

Mah pointed out how it gave "almost all Singaporeans a home of their own… that grows in value over time," rejecting a suggestion by the Workers' Party that the the prices of new flats should be pegged to the median income in Singapore.

And then-Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew's comments in 2012 further reiterated the government's plan for property to be an appreciating asset. Lee said:

"Those who held on to their homes, I've seen their property values going up five times, 10 times, 15 times, 20 times."

It is clear that the government (and existing homeowners) would see rising property values as a good thing. After all, as Lee said:

"This was the plan which we had from the very beginning — to give everybody a home at cost or below cost. And as development takes place, everybody gets a lift, all boats rise when the tide rises."

But the situation would no doubt be quite different for someone seeking to purchase their first home, as they would need to be able to keep up with ever-increasing property prices.

Even then, the possibility of SERS coming in near the end of a HDB flat's lease may have moved some to fork out high prices.

As National University of Singapore (NUS) sociologist Tan Ern Ser told CNA:

"I reckon the years of experiencing asset enhancement and social upgrading have been deeply ingrained in the Singaporean psyche. Moreover, they also believe that at some point, the expiring lease would be reset via en bloc."

March 2017: Wong's warning

In March 2017, then-Minister for National Development, Lawrence Wong, saw fit to respond to the phenomenon of aging, short-lease HDB flats being sold at high prices, as reported in Lianhe Zaobao.

In a post on the MND blog site (yes, MND had a blog), Wong cautioned against buying an older resale flat at a high price in anticipation of SERS.

Wong warned that HDB flat prices would inevitably start to fall at some point, as their leases run down.

He wrote that "buyers need to do their due diligence and be realistic when buying flats with short leases".

A few months later in June 2017, SLA made its announcement about the Geylang properties.

Leasehold vs HDB

Three years on, the Geylang owners seem to be handling their situation perfectly fine. Most of the owners have already moved out, and some have even surrendered their properties ahead of time.

Might HDB-owning Singaporeans one day hand their keys back to HDB at the end of their 99-year lease, with similar serenity? Perhaps.

But there is a difference between the Geylang leasehold owners and HDB owners: the former group was never told that their property was going to be an appreciating asset, nor did they benefit from the upgrading programmes which fuelled such appreciation.

Their properties' value would no doubt have appreciated handsomely at some point in the 60 years (especially given the low initial selling price). However, this was arguably the result of market forces, and not an exuberant resale market buoyed by, among other things, the illusory notion that the government would pay handsomely for aging flats en masse.

Still, as the 2017 warning from MND shows, the government has clearly stopped touting asset appreciation in the way it did in the 1990s.

Furthermore, the nature of HDB upgrading has evolved.

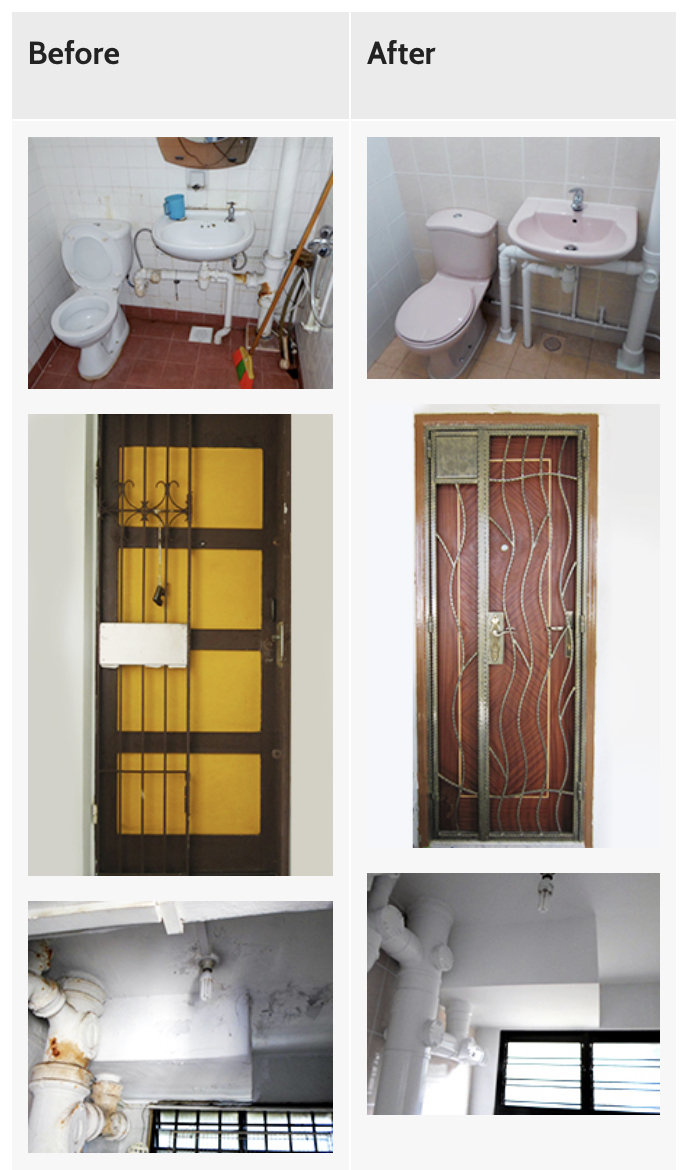

As Holland-Bukit Timah MP Liang Eng Hwa noted in Parliament in 2008, the earlier Main Upgrading Programme (MUP) — launched in 1992 — was comprehensive, transforming "basic and spartan" older flats with "a fresh look and better ambience".

In contrast, the Home Improvement Programme (HIP), which was announced in 2007, was "more maintenance in nature and hence would have lesser enhancement value to the flat owner."

Before and after the Home Improvement Programme. Screenshot via HDB website.

Before and after the Home Improvement Programme. Screenshot via HDB website.

Another thing to bear in mind is what Wong's cautionary blog post in 2017 reflects about the government's thinking: that asset appreciation could well get out of hand, and that it was something the government needed to be concerned about.

To extend the analogy of boats and tides used by then-MM Lee in 2012, a tide that rises too quickly might end up flooding some boats.

Today, resale flats past their halfway point of their lease continue to be transacted at high prices.

When will their value start to depreciate towards zero?

It will start to matter very soon, and buyers need to be aware that this is not a matter of if, but when.

Mothership Explains is a series where we dig deep into the important, interesting, and confusing going-ons in our world and try to, well, explain them.

This series aims to provide in-depth, easy-to-understand explanations to keep our readers up to date on not just what is going on in the world, but also the "why's".

Totally unrelated but follow and listen to our podcast here

Top image via Google Maps street view

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.