Nur Zaiya Naziha Binte Muhammad Saufi is like other babies in many ways: when she's content, she smiles happily in response to the people around her. When she's not, she cries until she's fed, held, or gets her diaper changed.

She weighs 4.27kg, which is a normal size for a two-month-old — Zaiya, however, is actually seven months old.

On Mar. 27, 2020, Zaiya was born almost four months premature, at the gestational age of only 23 weeks and 6 days.

She weighed only 345 grams, less than a small loaf of bread.

Internationally, a premature birth refers to babies born before 37 weeks while those born before 28 weeks are considered extremely premature.

At slightly below 24 weeks, Zaiya was considered not just extremely premature, but had extremely low chances of survival. After all at this stage, a fetus' lungs and its internal systems have not developed fully.

For premature babies, their growth development takes into account how premature they are, so Zaiya's growth is calibrated to that of two-month-olds, even though she is seven months old.

Perched on her mother Rohani Binte Mustani's knee, wearing a pink floral bib and bow, Zaiya looks happy and healthy, albeit still on the smaller side of two-month-olds, at 4.27 kg.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

But the journey to where she is now was not easy.

Only had two hours to decide

In the week leading up to Zaiya's birth, Rohani felt some abdominal discomfort, but figured they were just regular gastric pains.

On Mar. 26, she went into the A&E at the National University Hospital (NUH) thinking that it would be a quick visit and she would go home after receiving some medication.

Instead, the doctors told her that she had severe pre-eclampsia, a dangerous complication in pregnant mothers that involves high blood pressure.

The pre-eclampsia had caused Rohaini's blood pressure to skyrocket and so she needed to deliver Zaiya immediately. Otherwise, it could put Rohani's life at risk.

"It was actually between either me or her," Rohani explained.

At 23 weeks and 6 days, Zaiya's birth was just short of what would be considered a "viable" pregnancy of 24 weeks. Doctors at NUH gave her a 20 per cent chance of survival.

Rohani and her husband, Muhammad Saufi Bin Yusoff, were given only two hours to decide what to do: give birth and hope their baby survives, or terminate the pregnancy.

Dr. Zubair Amin, head consultant of the Department of Neonatology at National University Hospital advised Rohaini to proceed with the delivery and let the hospital care for the newborn.

In the end, the couple decided to go ahead with the delivery. Rohani said:

"20 per cent is still hope, rather than no hope. I decided just to go with it. Whatever happened after that, I just leave it to fate."

ICU and recovery

On Mar. 27, Zaiya — the smallest and most premature baby ever discharged from NUH, and perhaps in all of Singapore — arrived into this world via emergency caesarean section.

At 345 grams, she was only the size of a palm, and her arms and legs were the size of adult fingers.

Zaiya on the first day she was born. Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

Zaiya on the first day she was born. Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

The first thing most parents want to do after their child is born is to hold their baby in their arms.

Rohani and Saufi were unable to experience this with Zaiya though, as she was whisked away immediately after her birth to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

In fact, the parents weren't able to touch Zaiya for several months, because she was so fragile and vulnerable to the risk of infection.

"Do you know how painful that is for a mother? I could not even hug her, touch her fingers. I could only see her.

The only time I could see her [in the flesh] was when they changed her diaper, when they lift up the incubator glass, then I could actually see her face-to-face, but I couldn't touch her."

The first few days after an extreme premature birth are the riskiest, because their lungs are underdeveloped, explained Dr. Krishnamoorthy Niduvaje, a senior consultant in NUH's Department of Neonatology.

Doctors try to expand their lungs using medicine, but even so, these newborns' lungs may still be underdeveloped and may need ventilator support for weeks or months.

Zaiya was on a ventilator for about three months. Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

Zaiya was on a ventilator for about three months. Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

"Most babies outgrow their respiratory issues," explained Krishnamoorthy. "But the more premature the baby, the higher the risk of having these lung problems."

Zaiya also went through blood transfusions and took medicine to close a hole in her heart, known as patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

This is an opening, between the two major blood vessels leading from the heart. For most babies, the PDA will shrink and close on its own in the baby's first few days, but it takes much longer for premature babies' PDAs to close. And if it doesn't close, more blood goes to the baby's lungs, which can cause problems.

Luckily, Zaiya's PDA was able to close without the need for an operation thanks to medication.

She also had an operation on her eyes, because of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), a well known complication of extreme premature birth which can cause scarring, detachment of the retinas, or even blindness.

Rohani and Saufi visited her every single day, but because of Covid-19 regulations, would have to take turns entering the NICU to look at her through the glass, as they were usually not able to go in together.

The nurses were extremely helpful, updating Rohani and Saufi on Zaiya's condition, such as her weight gain and eating habits.

About three months after her birth, Zaiya was transferred out of the incubator and into a normal cot.

After months of only seeing her through glass, Rohani and Saufi were finally able to hold their daughter.

Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

"That's the first time I could touch her. I was so heartwarming, that finally I could touch her. This is the baby I gave birth at 345 grams. She survived."

Discharged home on Aug. 5

On Aug. 5, Zaiya was discharged from the hospital. She was healthy, didn't need medication or breathing assistance.

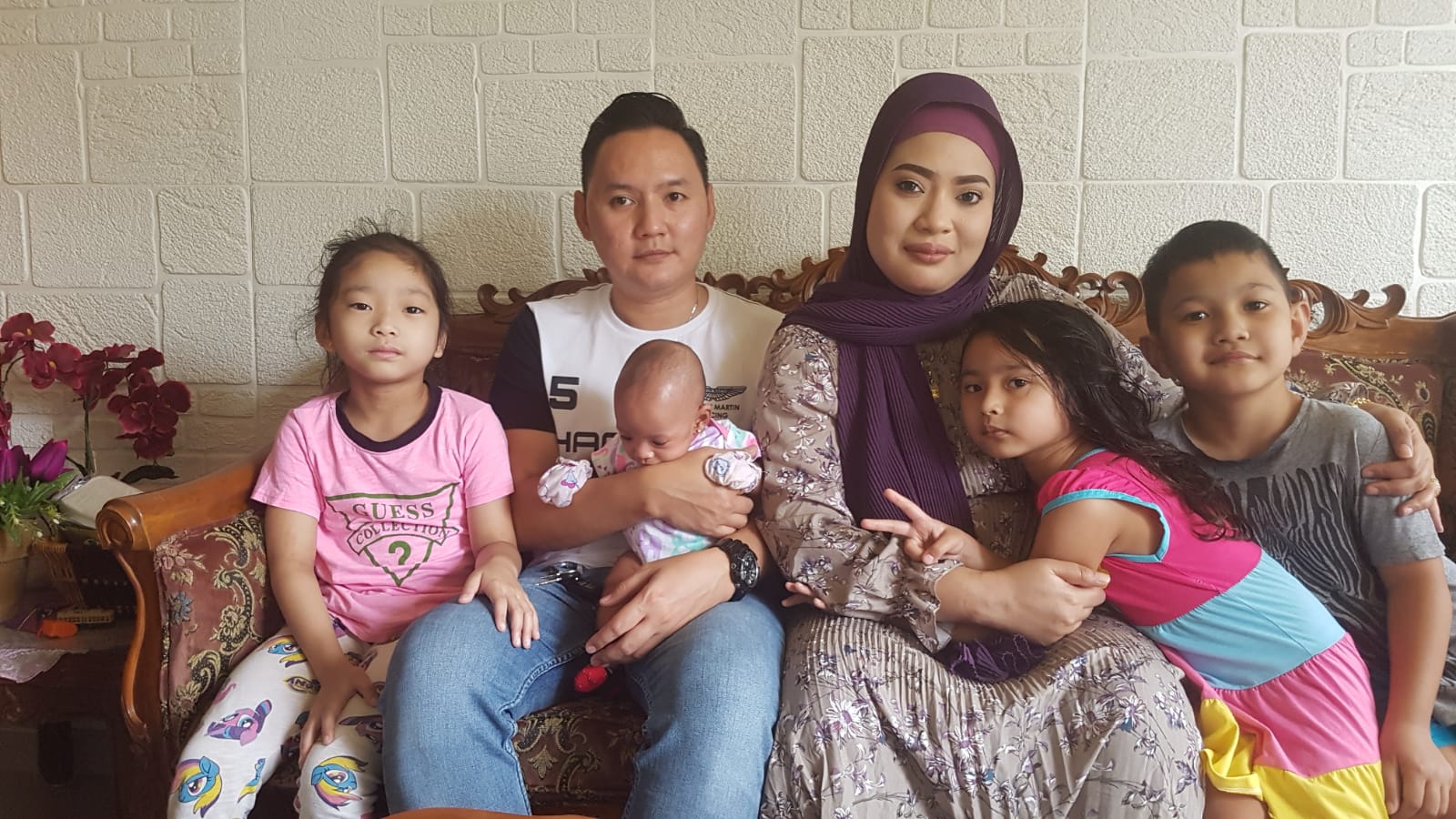

For first time, her grandparents and three older siblings — ages seven, six, and four — were able to see her, as they had been unable to visit her in the hospital due to Covid-19 regulations.

Rohani and Saufi with Zaiya and their other three children. Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

Rohani and Saufi with Zaiya and their other three children. Photo courtesy of Rohani and Saufi.

On Zaiya's first day at home, Rohani couldn't sleep, fretting over her newborn constantly:

"Obviously, when I brought her home, the first day I couldn't sleep. Because as a mother, I was checking, is she breathing? Is she coping well?

Because we don't have the equipment such as in the hospital to [call for help] if anything goes wrong. It's all by motherly instinct."

Today, Ziya is healthy and on par with other two-month-old (taking into account her prematurity) babies' developmental milestone.

Doctors will keep monitoring her over the coming months and years. By the time most premature babies grow to two or three years old, Krishnamoorthy explained, they would have caught up with their full-term peers.

The past few months haven't been easy, says Rohani: "It's a journey, lah."

Nor has the journey been cheap. Rohani and Saufi have spent more than S$50,000 on Zaiya's treatment — after subsidies — in her first seven months of life.

But thanks to the hard work of the nurses, doctors, and family support, Zaiya has pulled through.

"We are indebted to the nurses, to the doctors, for taking such good care of her during her stay in this hotel," Rohani says, laughing.

And Rohani, Saufi, and the family are just happy to have her home with them:

"The first few months have been very joyful, because I just want her to be home."

We deliver more stories to you on LinkedIn

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top photos courtesy of Rohani and Saufi, and NUHS.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.