The year was 1986.

The massive undertaking to clean the Singapore River of filth and human detritus was nearly complete, the first Town Councils were established, and air-conditioned buses just started plying the streets. It's a year of change, with the tiny island state still reeling from the 1985 recession.

Singapore was still in the midst of transforming into then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew's vision of a flourishing "Garden City".

And while tens of thousands of trees and shrubs were being planted across the island to create the rain tree and bougainvillea-lined streets Singapore is so famous for today, the island was undergoing intensive urban development.

Yet, an untouched haven sat at the northwestern tip of Singapore.

It is this secluded patch of mangroves, where the seed of bottom-up conservation was planted, and which has since grown to become a precious sanctuary for the nature community.

An untouched gem

It was in this year that Malaysia-born Ho Hua Chew stumbled across the mangroves in Sungei Buloh wetlands.

Ho had returned to Singapore in the early 80s after completing his post-graduate studies in Washington, U.S., with his wife.

Having picked up birdwatching while abroad, he joined the Nature Society Singapore's (NSS) Bird Group.

The NSS, then known as Malayan Nature Society, is one of Singapore's oldest non-governmental organisations, and its roots can be traced as far back as 1921.

Upon his return, he decided to explore the local countryside for more birdlife, believing that he "should get to know it in a more intimate sort of way".

It was during this period that Ho first discovered Sungei Buloh, after catching wind of its existence from fellow birdwatcher and NSS member Richard Hale.

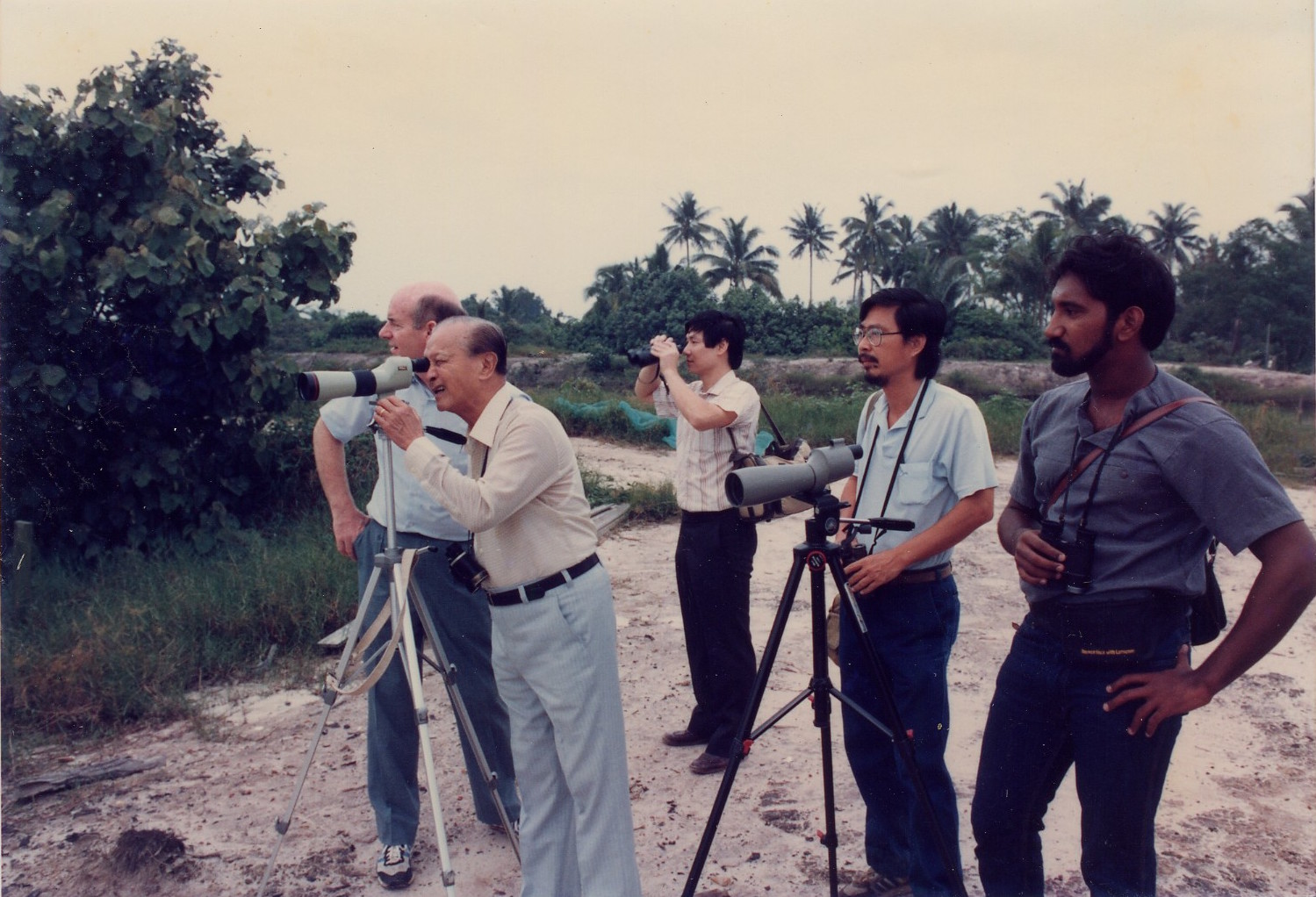

Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

Speaking to Mothership, Ho described his absolute awe at unearthing this hidden gem.

"When I was informed of it by Sutari, another Bird group member, who got the news from Mr Hale, I went to recce the area with Sutari and was simply amazed with the tremendous flocks of the shorebirds feeding and wheeling about over the mudbeds of the fish ponds in the area."

To be cleared for agrotechnology

Ironically, Sungei Buloh was originally designated as a forest reserve in 1890 until its status was altered in 1938.

The wetlands, which back then was degraded and merely consisted of ponds and mudflats, yet home to an unexpected trove of biodiversity, was slated for development for intensive agrotechnology.

As the brackish mangrove water and waterlogged mud contained plenty of organic nutrients, the area was ideal for prawn farming.

Having just discovered Sungei Buloh, Ho was unwilling to leave it to the bulldozers.

His desire to protect Sungei Buloh was further spurred by the recent loss of another piece of wetland — the Sungei Serangoon estuary, which had been converted into a dumping ground despite being renowned as a haven for migratory shorebirds.

Nine months of creating a conservation proposal

Ho and several others from NSS sprang into action.

A team was formed to formulate a proposal for Sungei Buloh's conservation.

Coming up with the proposal was no walk in the park. It took around nine months, and the team had to meet once a month at various venues for discussion.

Conservation and civic society at the time in Singapore was in its fledgling stages.

Noting that the existing climate then was of prioritising socio-economic development, the process of formulating the proposal was "slow" and "cautious".

Only in December 1987, did a group of six comprising Ho, Hale, former National University Singapore lecturer Clive Briffet, the late conservationist and veteran wildlife consultant Subaraj Rajathurai, ornithologist Christopher Hails, and surgeon Rexon Ngim, finalise the proposal.

The result was an illustrated booklet highlighting the richness of Sungei Buloh. Describing it as an area rife with potential and a "veritable microcosm of culture and natural history", the proposal was specifically geared towards pointing out the economic, human benefits and educational value conserving this piece of nature would bring.

Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

It also included an inventory of the birdlife there and suggestions on how the area could be managed, such as a visitor centre and a programme of guided walks and farming tours.

The proposal was subsequently distributed to anyone of importance — permanent secretaries, ministers, MPs, as well as the prime minister and president.

Giving then-President Wee Kim Wee a tour

Ho and the NSS's efforts weren't for naught.

Perhaps due to the passion with which the group sought to lobby for this untouched piece of nature tucked away in urbanising Singapore, they even managed to snag then-president Wee Kim Wee for an unofficial visit to the site.

Recounting it as one of his most memorable moments at Sungei Buloh, Ho said it was a very "relaxing event with no protocol and hurry like an official visit".

Leaving behind his entourage, Wee merely had his aide-de-camp by his side.

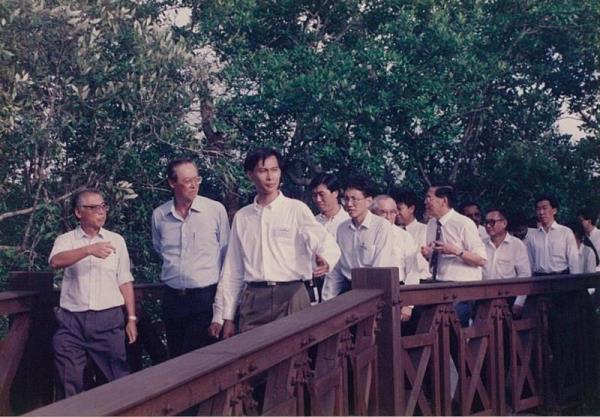

Ho (rightmost) as part of the group escorting then-President Wee Kim Wee through Sungei Buloh. Photo courtesy of Nature Society Singapore

Ho (rightmost) as part of the group escorting then-President Wee Kim Wee through Sungei Buloh. Photo courtesy of Nature Society Singapore

Ho and the five other men in the group accompanied the president to a pond where a surprise picnic table heaped with snacks and drinks had been set up by Wee's staff.

It served as the perfect vantage point to observe the shorebirds ambling on the mudflats.

"We could see that [Wee] enjoyed the experience as well, seeing with his own eyes the spectacular vast flocks of shorebirds like plovers, sandpipers, egrets, etc. that took off in unison from the mudbeds and flying around low in the sky above and landing like confetti again."

It was a "pleasant" experience, Ho said, "a sumptuous makan, out there in the open countryside!"

Photo courtesy of Nature Society Singapore

Photo courtesy of Nature Society Singapore

A milestone for civic society

And perhaps it was that intimate visit to Sungei Buloh which finally convinced Wee and the authorities.

On Apr. 8, 1988, then-Minister for Foreign Affairs and National Development S. Dhanabalan announced that 85ha of Sungei Buloh would be set aside as a bird sanctuary.

S Dhanabalan (left with binoculars) and Goh Chok Tong (right in brown). Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

S Dhanabalan (left with binoculars) and Goh Chok Tong (right in brown). Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

A total area of 87ha was eventually designated as the new Sungei Buloh Nature Park in 1989.

Although this fell short of the 318ha originally proposed, a study conducted by Hails had deemed the area sizeable enough to support birdlife.

Nevertheless, this concession was a minor issue in light of the major breakthrough Ho and friends had made — it was the first time Singapore had set aside any plot of land for conservation since its independence.

In a country and era where most tend to duck their heads in the face of nationwide change, the protection of Sungei Buloh marked a historic moment both for nature conservation and civic society here.

Ho said that although the period prior to the announcement was "pretty exciting", he and the others had not been too confident of success.

He told The Straits Times that many others were pessimistic about the outcome, telling him: "Don't hope for it."

The success thus came largely as a surprise, and Ho humbly said that perhaps they had been "lucky".

Ho (leftmost) with visitors. Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

Ho (leftmost) with visitors. Photo from Nature Society Singapore via PictureSG

Nature park to nature reserve

The subsequent conversion of the rather bare-bones mudflat to a full-fledged nature park — including the installation of footpaths, boardwalks, a visitor centre and bird observation hides — cost S$8.5 million.

View of the main bridge in 1993. Photo from NParks

View of the main bridge in 1993. Photo from NParks

The entire operation involved collaboration between various government agencies and the NSS.

Special care was taken to maintain the ecological integrity of the site. For example, the boardwalks were built by hand instead of utilising heavy machinery.

Sungei Buloh Nature Park was officially opened by then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong on Dec. 6, 1993, and attracted 17,000 visitors in its first month.

Goh Chok Tong (second from left), walking along the Main Bridge during the park's opening ceremony. Photo from NParks

Goh Chok Tong (second from left), walking along the Main Bridge during the park's opening ceremony. Photo from NParks

Almost 10 years on, it could be said that Ho's efforts culminated in the gazetting of 130ha of Sungei Buloh as a nature reserve in 2002, marking it as the only wetland reserve in Singapore.

An important site for diverse wildlife

Since then, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (SBWR) has transformed into a beloved spot for avid birdwatchers, or just a secluded place for visitors to escape the hustle and bustle of city life and immerse themselves in the sights and sounds of nature.

The mangroves and mudflats serve as an important stopover for migratory birds from all around the world, and about 62 species of birds were recorded on its shores in the year 2000.

A flock of Common redshanks. Photo from Brian Jefferly Beggerly / Flickr

A flock of Common redshanks. Photo from Brian Jefferly Beggerly / Flickr

From August to September every year, thousands of these birds drop by from as far as Russia, Mongolia, North China, Japan and Korea to rest or roost.

Some stop briefly before heading onwards to Indonesia, Australia and New Zealand, while others spend the winter here until March or April before flying back to their breeding grounds in the Northern Hemisphere.

A Mongolian plover. Photo from Lip Kee / Flickr

A Mongolian plover. Photo from Lip Kee / Flickr

Sungei Buloh isn't only home to diverse birdlife: It is host to 27 of the world's 70 species of mangroves, monitor lizards, mudskippers and the native Estuarine crocodile, the latter of which regularly sparks some healthy fear and excitement whenever spotted.

Decades after pioneering conservation in Singapore, the now 74-year-old Ho shares that he still visits Sungei Buloh every "now and then".

Whenever rare or endangered bird species turn up, such as the locally-extinct Lesser Adjutant stork from across the Johor Straits or a nesting Buffy fish owl, Ho makes a point to head down.

Not only has Sungei Buloh served as a crucial habitat for wildlife, but it has also brought together and anchored a tight-knit community of birdwatchers and nature lovers.

Photo from Rotary Club of Jurong Town, Singapore / FB

Photo from Rotary Club of Jurong Town, Singapore / FB

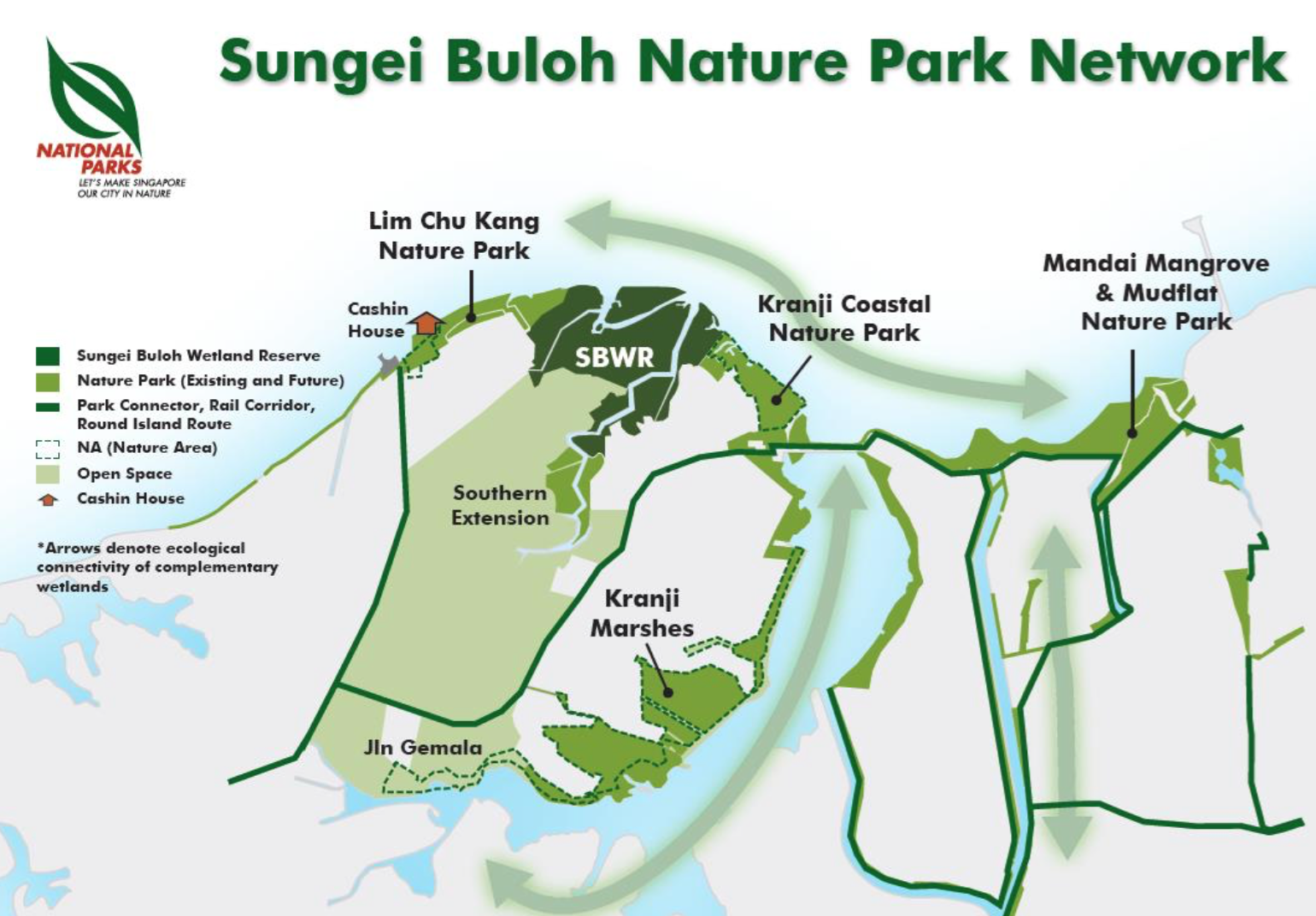

A 400ha green network by 2022

In August earlier this year, Minister for National Development Desmond Lee announced NParks' renewed efforts to enhance Singapore's natural capital to evolve the country into a "City in Nature".

Various green spaces in the northwest of Singapore will be combined to form a new Sungei Buloh Nature Park Network that will span 400ha and is slated for completion in 2022.

The network will comprise the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, as well as other important core habitats like the Mandai Mangrove and Mudflat, Kranji Marshes, parks, eco-corridors and nature areas, such as Jalan Gemala and Kranji Reservoir Marshes.

In total, this is three times the size of the original wetland reserve, about half the size of Toa Payoh town.

These green spaces, when included as part of the network, will help to act as buffers to the reserve.

This transformation of Sungei Buloh is an impressive feat — considering how the formerly barren mudflats have grown alongside rapidly developing Singapore — something which must have been even more of a sight to behold for a pioneer like Ho, who himself had a hand in its growth.

"It's simply great!" Ho said, describing this evolution from mudflat to nature park network as a "big splash for the government’s "City in Nature" thrust.

Ho with Minister for National Development Desmond Lee. Photo from Desmond Lee / FB

Ho with Minister for National Development Desmond Lee. Photo from Desmond Lee / FB

Ho marvelled:

"Buloh wasn’t even a mangrove area when we first proposed for its conservation; it was almost bare and treeless with just aquaculture ponds and mudbeds and bunds around these ponds. Now the mangrove is almost everywhere in the area, growing luxuriantly, providing cooling shades and shields for visitors strolling along the bunds."

Ho added that not only will the green network benefit species in Singapore, protecting the northwestern coast of Singapore will simultaneously promote the survival of species from across the Johor Strait that take refuge here.

Room for improvement

Despite his clear admiration for what Sungei Buloh has become, and true to the conservationist in him, Ho has plenty of suggestions for improvement.

He pointed out that any areas towards the seaward border of the mangroves should be conserved, and should not even be touched by the construction of recreational paths or park-connectivity routes, so as not to disturb wildlife feeding or nesting in those areas.

Ho also hopes the network can stretch across Lim Chu Kang, which will be converted into a new nature park as well, all the way to the Western catchment to encompass the existing mangrove and forest patches at Sungei Melayu.

Additionally, Ho expressed concerns about the agricultural area bordering the southern side of the Sungei Buloh Nature Park Network.

"There is a need to have proper control of the farming activities going hereabout so the Buloh Park Network will not be subjected to the risk of pollution," Ho said.

The road of activism hasn't been a bed of roses for Ho though, and despite the tremendous success of Sungei Buloh, subsequent attempts to save other plots of land, such as the Senoko wetlands in the 1990s, fell through.

Nevertheless, Ho holds out hope, citing the government's willingness in recent years to listen to the public's voice.

And despite all that he has accomplished in the past decades and the generations of young activists and nature lovers he has inspired, Ho remains humble and modest.

"I don't have a talent for administration. We're amateurs. We fumble, we struggle... I concentrate on the birdlife. If you believe in a cause, that nature has value, you just push on."

We deliver more stories to you on LinkedIn

Top photo courtesy of Nature Society Singapore and from NParks

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.