In about a month, Corporal First Class Oliver Yeo will be finishing his full-time national service (NS).

But unlike most who come to the end of their two years in the military, Yeo tells Mothership that his last day will be quite a sad one.

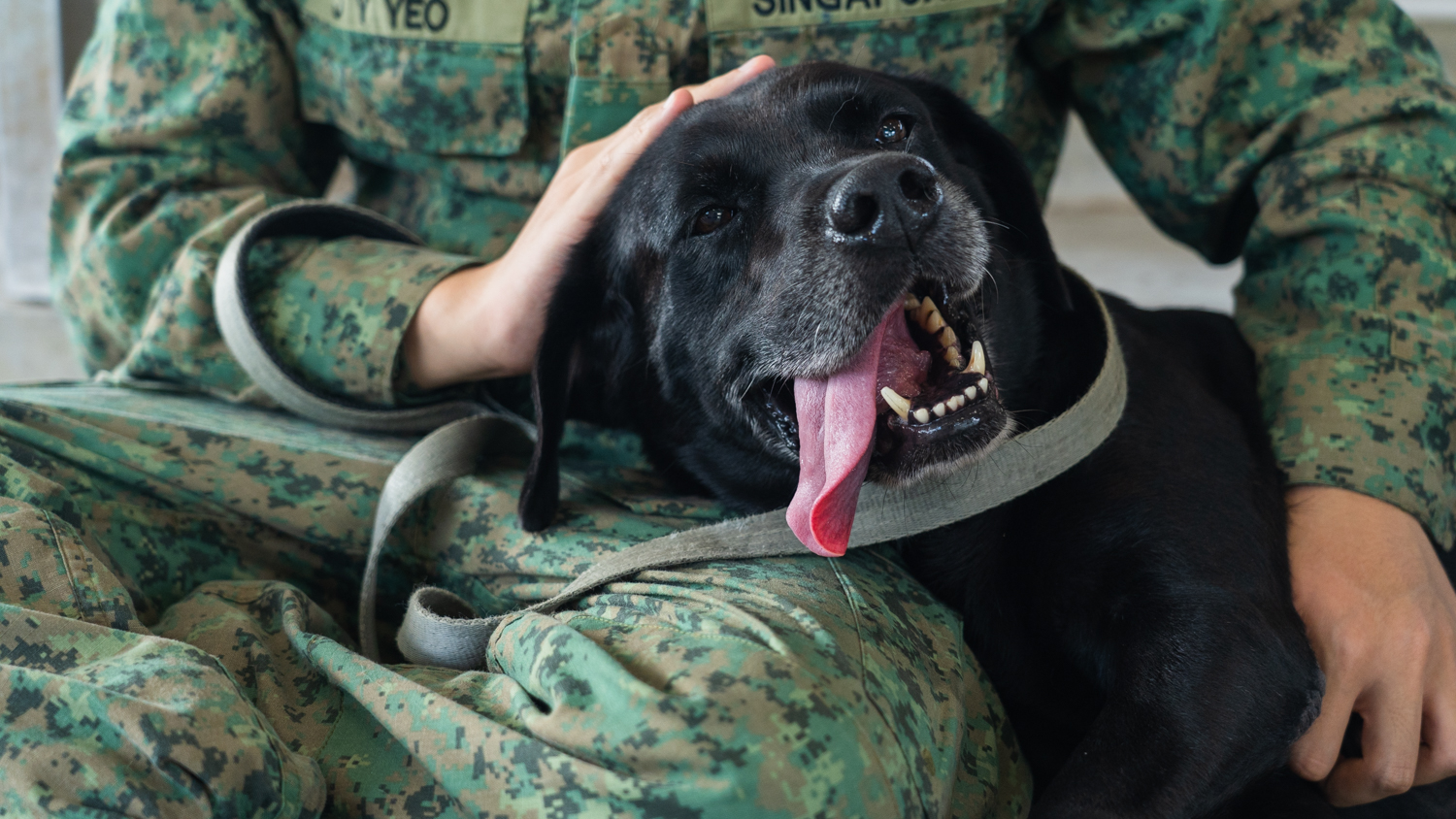

That’s because Yeo has spent most of his national service in the Singapore Armed Forces’ (SAF) Military Working Dog Unit (MWDU) with his partner Jack, a placid black Labrador.

Jack is one of the unit’s sniffer dogs and also Yeo’s favourite.

“He’s the most bubbly dog I’ve ever seen in this unit,” says Yeo. The 22-year-old is speaking to me in a training shed at the MWDU’s headquarters in Mowbray Camp.

“I really like to take him out and play around and hang out with him.”

The Military Working Dog Unit

The MWDU has about 100 dogs under its watch any at one time. They’re generally split by the type of functions they perform. Labradors and Spaniels are utilised as sniffer dogs.

Guard dogs, on the other hand, are mostly German Shepards or Belgian Malinois.

In days gone past, Jack was utilised by the unit to sniff out explosives or illicit substances.

He went through about two to three months of training by SAF regulars, teaching him to follow basic commands and complete operational tasks.

At the end of the training course, Jack and the rest of the dogs had their very own passing out parade.

The passing out ceremony where the military working dogs (new guard dogs) have completed their 10-weeks training course in April 2019. Image courtesy of MINDEF.

The passing out ceremony where the military working dogs (new guard dogs) have completed their 10-weeks training course in April 2019. Image courtesy of MINDEF.

"It's quite an intense experience"

Standing behind a fence enclosing a paddock, I watch as Kita — a guard dog — performs an attack-training drill.

She sits by her handler’s side before a command sends her scampering in the direction of another oncoming handler, who is acting as an aggressor. As she closes in, Kita launches herself off the ground and locks her jaws around her target’s arm — protected by a heavy-duty bite sleeve.

A few commands later, the Belgian Malinois is back sitting calmly at her handler’s side.

Taking part in the attack drill — as bait — is something that all MWDU dog handler trainees have to do.

Corporal Shaaman Srikanth still remembers the very first time he stood in the paddock wearing the bite sleeve.

“I thought of myself as a very brave person,” he tells me.

“But when you actually encounter the dog coming towards you to attack, it’s quite an intense experience.”

Regardless, the exercise is very safe, the 20-year-old is quick to add.

“Our dogs are very well trained… They know how to handle the trainees. They’re better trained than the trainees most of the time.”

Bonding with the dog

The ferocious guard dogs that I saw growling through their muzzles and pulling their leashes taut leave a strong first impression, which is why it’s hard to imagine why Shaaman describes them as “very affectionate” — at least until you’ve bonded to them.

“That’s part of their deployment,” he says about the guard dogs' more energetic demeanour.

“As you grow a bond with them, as you take them out more often, [and when] you get deployed to ops with them, you actually tend to look at them in a very different light. They become very affectionate towards you.”

According to Yeo and Shaaman, the process of bonding with a dog can take up to two months.

Each handler at the MWDU has up to three dogs that they work with on a regular basis.

Every day, handlers take the dogs out from their kennels for feedings, exercise, cleaning, grooming, and training.

They also spend time cleaning out the dogs’ kennels and have time to play and hang out with their furry friends.

Each of these interactions, Shaaman says, is an opportunity to bond.

Yeo knew that he was bonded with Jack when the Labrador started to show affection to the national serviceman.

“When others take out Jack, he’ll tend to rush and dash towards me instead of the other handler. And sometimes when I leave him alone — when I have something else to do — he’ll bark for my attention, wanting me to go back to his side.”

Yeo and Jack. Image by Andrew Koay.

Yeo and Jack. Image by Andrew Koay.

"He already knew what I expected of him"

Apart from the warm vibes, bonding with a dog actually makes the handler’s job a lot easier during operations or training.

“You can do things without you actually having to give the full command,” explains Shaaman. His primary — and favourite — dog is a majestic German Shepherd guard dog named Arras.

Recalling a training sequence he had to perform with Arras in front of some new trainee handlers, Shaaman remembers the nerves he was feeling. He wondered if the German Shepherd would react obediently in the presence of the trainees, who were complete strangers to the dog.

“That’s when I really knew I had bonded with Arras. Without having to give the full commands or the full hand gestures, just by the slight movement of my hands or a bit of my voice, he already knew what I expected of him, and he could act accordingly.”

Handling the dog can depend just as much on the handler’s temperament and skill too. Yeo tells me that the more wily dogs can sometimes run circles around a naive soldier.

“Depending on the way you handle them, they may respond differently. Some of these dogs really know how to take advantage of a handler if they don’t handle them properly.”

Retirement and adoption

As I watch Yeo — a veterinary assistant at the unit — go through a routine medical check-up for Jack, the bond between the two is evident as the Labrador dutifully follows its handler around the vet’s office.

Yeo speaks softly to the canine, almost as if it were a human, and it responds with uncanny obedience.

At nine years of age, Jack is currently enjoying life in retirement.

Dogs at the MWDU are generally procured when they are one year old, and work until the age of eight.

Once they’ve retired, the unit seeks new homes for canines through the SAF’s yearly adoption drive.

In between, handlers get them ready for their golden years by making sure they’re well-groomed and showered with love.

Dogs who aren’t adopted remain with the unit where handlers continue to care for them.

“It definitely feels quite sad to leave this dog,” says Yeo, speaking about his impending operationally ready date and the possibility of Jack leaving the unit.

“But I’m much happier for the retired dogs, because they’re going to be adopted into a loving home and going to be showered with love and affection.

Especially after they’ve been in service for (six) or more years, they definitely deserve it.”

Yeo says that he hopes to continue visiting Jack at his new home in the future.

The happiest unit in the army

Meanwhile, Shaaman is seated legs crossed on the floor, as Arras lays his head in his handler’s lap.

It is grooming time, and Shaaman is shaving excess fur from Arras' black and golden coat.

Outside the grooming area, a prospective adopter observes the proceedings. I’m told that the burly, tattooed man used to be a handler himself.

Shaaman still has about a year of national service to go, though he already has exciting plans for his future. He’ll be travelling abroad to further his studies at an overseas university.

However, right now he’s just savouring each moment at the unit, with his dogs.

“It’s never a sad day here,” he says.

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top image by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.